“Shelter from the Storm” presents a panorama of asylum – the protective immigration status many migrants have sought at the U.S. southwest border – from shifting angles of experience, law, demography, economics, history and politics.”

~ ~ ~

[...]]]>“Shelter from the Storm” presents a panorama of asylum – the protective immigration status many migrants have sought at the U.S. southwest border – from shifting angles of experience, law, demography, economics, history and politics.”

~ ~ ~

“Ana and her teenage daughter Teresita (not their real names) fled their home in a Central American city after a local gangster put a gun to Teresita’s head and told Ana that he would kill her daughter if she didn’t pay protection for her little corner store. After eight days of travel, they arrived at what Mexicans call el río Bravo and got into an inflatable boat. In the middle of the river, it started leaking air. Ana, who does not know how to swim, tried vainly to stop the leak with her hands. Teresita can swim, so Ana gave her the plastic bag with their papers and IDs. Mother and daughter clutched each other.”

~ ~ ~

“Asylum means protection against being sent back to a home country where you might be persecuted. It’s recognized as a fundamental human right by United Nations treaties, and protected by international and U.S. laws. Asylum and refugee status are both granted in cases of ‘well-founded fear of persecution based on race, religion, membership in a particular social group, political opinion, or national origin.’”

~ ~ ~

This 71-page report is heavily footnoted and referenced. It can be downloaded as a PDF file from:

Google Drive: https://bit.ly/3g2lzfI

OneDrive: https://tinyurl.com/storm-2020

For an informative overview of the legalities of asylum, see the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project webcast, “Asylum for Beginners” - video & slides. Thanks to NWIRP for linking to this paper.

Some of my previous stories on immigration include:

“In the Footsteps of the Millennium Migration – download” (footnoted report). Crossover Dreams – Huffington Post, October 12, 2017. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/in-the-footsteps-of-the-millennium-migration-download_us_59dffb37e4b09e31db9757cd

“How the ‘Millennium Migration’ from Latin America Shaped the U.S. for the Better”. Foreign Policy In Focus, October 30, 2017. https://fpif.org/millennium-migration-latin-america-shaped-u-s-better

“Manufacturing illegality: An Interview with Mae Ngai”. Foreign Policy In Focus, January 16, 2019. https://fpif.org/manufacturing-illegality-an-interview-with-mae-ngai

“‘Being Tortured Has Been the Best Experience of My Life’”. Foreign Policy In Focus, September 25, 2015. https://fpif.org/being-tortured-has-been-the-best-experience-of-my-life

I’ve also published over 20 pieces on immigration and related topics on Inter Press Service:

http://ipsnews.net/author/peter-costantini

]]>

United Steel Workers members in big march – Credit: Casey Nelson

Demonstrators blocking street – Credit: Casey Nelson

One afternoon during the 1999 Seattle Ministerial of the World Trade Organization, the police and the Black Bloc were mixing it up on Pike [...]]]>

United Steel Workers members in big march – Credit: Casey Nelson

United Steel Workers members in big march – Credit: Casey Nelson

Demonstrators blocking street – Credit: Casey Nelson

Demonstrators blocking street – Credit: Casey Nelson

One afternoon during the 1999 Seattle Ministerial of the World Trade Organization, the police and the Black Bloc were mixing it up on Pike Street amid clouds of tear gas. As I retreated from the front lines, I heard music and looked up. On a balcony high on a condo tower, someone had cranked up a big sound system, and Jimi Hendrix was shredding “The Star-Spangled Banner” over the suddenly mean streets.

The Wall Street Journal called the event “the Woodstock of antiglobalization”. But the WTO protests were far more than just a counter-cultural jamboree. This time around, it was the WTO organizers, Clinton administration officials, and City of Seattle hosts who must have felt like they had dropped some of the bad acid.

The Battle of Seattle, for which the volunteer DJ provided an ironic sound track, can’t be reduced to a couple of hundred black-clad, masked “anarchists” breaking a few storefront windows, or the police pepper-spraying peaceful demonstrators.

Jimi’s fuzz, feedback, and howling riffs rocked the zeitgeist of a historic inflection point: the implosion of a market-fundamentalist model of globalization pushed by the richest countries and transnational corporations. On the streets and in independent forums, it was represented mainly by a convergence of labor, environmental, public-health and democracy movements from the far corners of the world, many of which rarely had a chance to dialogue in person. Their march of at least 40 thousand people was complemented by artful and effective civil disobedience by thousands more, who managed to non-violently shut down the planned opening of the Ministerial.

What was not apparent outside the Convention Center was that inside, many delegates from developing countries and opposition organizations were inspired by the energy of the streets. They brought to Seattle many long-standing grievances against aspects of the WTO model. But the protests emboldened some to stiffen their resistance to the hosts’ heavy-handed insistence on an expanding agenda of trade orthodoxy.

I covered the festivities as a member of a team of four journalists writing for Inter Press Service, a global non-profit newswire based in Rome. Abid Aslam had been covering international institutions and economics for many years, and was able to buttonhole delegates and observers from developing countries by name and sit down with them for coffee. Danielle Knight was a veteran chronicler of international environmental issues. Casey Nelson, my nephew, was press-ganged into serving as our photographer, and did not flinch as he gamely dodged the stun grenades.

Below you’ll find links to the articles that we sent out on the IPS wire and a few not published there, along with two retrospectives written on the 10th anniversary in 2009.

The protests against the WTO unleashed flash floods of creativity. The most visible symbolism was probably the two big banners by the Rain Forest Action Network hung from a construction crane, one an arrow labelled “WTO”, the other an arrow labelled “Democracy” and pointing in the opposite direction.

One of my favorite exploits, though, involved 484 pounds of Roquefort cheese. French farmer José Bové, the crusty leader of the Confédération Paysanne (Peasants Confederation), reportedly smuggled it into Seattle and gave it away to passers-by outside a McDonald’s to dramatize what he saw as a particular injustice of the WTO.

Bové had won notoriety in France for driving his tractor into town and using it to pull the roof off of a McDonald’s under construction. His battle cry was “McDo dehors, vive le Roquefort” – “Out with McDonald’s, long live Roquefort cheese”. His WTO action, though, went beyond simple outrage at an affront to French gastronomy.

The European Union had banned beef treated with growth hormones as a threat to consumer health. However, such hormones were approved and commonly used in the U.S. The U.S. government rejected the ban as a trade barrier, brought a complaint against it in the WTO dispute settlement body, and won a judgement that allowed it to slap punitive tariffs on certain European food products, including Roquefort.

Bové was channeling the ire of many European consumers at the use of the WTO to shove down their throats a controversial agribusiness practice that they saw as unhealthy, and the results of which they had democratically decided they did not want to consume. Beyond the immediate issue, this case was emblematic of numerous efforts to use WTO provisions to roll back labor, human rights, environmental, consumer and health regulations in many countries, especially poor ones, in order to protect the profits of powerful exporters and investors and preserve the economic dominance of the wealthiest countries and enterprises.

Criticisms of the WTO at the Ministerial also targeted some tactics used by the WTO leadership and the biggest members to strongarm small, developing counties into accepting agreements expanding the scope of the trade organization.

“Green room meetings” were relatively small closed meetings of representatives of certain member countries hand-picked by the WTO leadership, tasked with reaching a preliminary agreement before taking it to the full membership. Many of the poorer countries saw them as a ploy to circumvent their participation in democratic decision-making on controversial issues.

On the final day of the Ministerial, I was sitting with Abid in the press room when someone came in and whispered something to one of the other journalists. The word quickly circulated that Director General Michael Moore and U.S. Trade Representative Charlene Barshefsky had convened a secret last-gasp green room meeting, inviting only selected U.S. allies, in hopes of approving a closing statement that they had drafted. We suspected that this might announce agreement on launching the new round of trade negotiations they were promoting.

A stampede of ink-stained wretches, the two of us included, thundered towards the conference room on another floor of the Convention Center where the meeting was going on. The organizers refused to let us in, and called security to hold us at bay. Testy scriveners banged on doors and walls and chanted loudly, bringing a little of the atmosphere of the streets into the suites. Finally, the meeting conveners relented and let us in. They had failed to reach the agreement they sought, and there was nothing left to conceal from us. The high drama of what was billed as an epoch-making conclave ended with a whimper of crestfallen officials and without a new round of trade talks.

The failure in Seattle to reach agreement on the expansion of the WTO through ongoing talks set a precedent. Each following ministerial failed to convince many of the developing countries, and many political forces within the industrialized countries, that the WTO was a fair forum for protecting their economic interests, reducing poverty, and fostering broader development. With the conflicts that flashed over in Seattle simmering unresolved, the next round of WTO negotiations never took place and the WTO was never expanded.

Ten years later, WTO Director General Pascal Lamy acknowledged that “Trade liberalisation has transition costs and not all segments of society reap the benefits of it. … Trade liberalisation creates winners and losers.” Beyond trade per se, the WTO and similar agreements have also drawn widespread criticism for creating incentives for unbridled foreign investment, enabling transnational corporations to strip away national and local safeguards for labor, the environment, and consumer protection. Rather than encouraging trade, these provisions promote outsourcing of jobs and a global race to the bottom on public regulation of corporate abuses.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership, the WTO’s regional progeny, was widely viewed as an effort to create a trade bloc to woo some Pacific Rim countries away from Chinese economic influence. In the U.S., however, significant forces across the political spectrum rejected the proposed agreement. President Donald Trump withdrew the U.S. from the TPP in 2017, and it is now defunct.

Beyond the TPP, Trump’s use of extortionate tariffs to launch trade wars with U.S. partners has effectively rendered any trade agreement signed by the U.S. a dead letter. He has demonstrated that the most powerful nation can simply ignore a basic premise of all trade treaties – negotiated settlement of disputes – and revert to 18th Century mercantilism in an effort to beggar its neighbors. So far, this does not bode well for the U.S. or world economies.

Despite these setbacks, the immense juggernaut of corporate-led globalization rumbles on, with or without trade agreements. A new effort to bring the digital economy – and particularly data, the new e-gold – under transnational corporate control has been proposed as a new “e-commerce” treaty within the WTO framework. NAFTA 2.0, a revision of the North American regional treaty, has been inked and is being debated in Congress. Nevertheless, efforts to use trade treaties to universally institutionalize some of neoliberalism’s worst abuses have not fared well in this millennium.

Twenty years later, it looks like the Seattle Ministerial will be remembered less as the WTO’s Woodstock than as its Waterloo.

IPS coverage

The Tear Gas Ministerial – December 1999

“The Tear Gas Ministerial: Introduction”. Peter Costantini, The Tear Gas Ministerial. November 1999 – January 2000.

http://users.speakeasy.net/~peterc/wto/wtoint.htm

“Free trade truck grinds theoretical gears”. Peter Costantini, The Tear Gas Ministerial. November 23, 1999.

http://users.speakeasy.net/~peterc/wto/theory.htm

(A shorter version ran on IPS as “TRADE: Free Trade Theory Takes a Beating”.

http://www.ipsnews.net/1999/11/wto-seattle-preview-following-is-another-in-a-series-of-special-ips-features-on-the-major-issues-at-the-wto-ministerial-conference-seattle-nov-30-dec-3-trade-free-trade-theory-takes-a-beating)

“Temblors shake World Trade Organization in Seattle”. Peter Costantini with Abid Aslam & Danielle Knight, The Tear Gas Ministerial. December 1, 1999.

http://users.speakeasy.net/~peterc/wto/temblors.htm

(A shorter version ran on IPS as “TRADE: WTO Talks Resume in Face of Protests.” http://www.ipsnews.net/1999/12/trade-wto-talks-resume-in-face-of-protests)

“HEALTH-TRADE: WTO Urged to Address Access to Medicine”. Danielle Knight, Inter Press Service. December 2, 1999.

http://www.ipsnews.net/1999/12/health-trade-wto-urged-to-address-access-to-medicine

“TRADE: Third World Tastes the Carrot and the Stick”. Abid Aslam, Inter Press Service. December 2, 1999.

http://www.ipsnews.net/1999/12/trade-third-world-tastes-the-carrot-and-the-stick

“TRADE: Developing Countries Assail WTO “Dictatorship’”. Abid Aslam, Inter Press Service. December 3, 1999.

http://www.ipsnews.net/1999/12/trade-developing-countries-assail-wto-dictatorship

‘”ENVIRONMENT: WTO Attacked for Ignoring ‘Precautionary Principle’”. Danielle Knight, Inter Press Service. December 3, 1999.

http://www.ipsnews.net/1999/12/environment-wto-attacked-for-ignoring-precautionary-principle

“Beardless in Seattle: Cuban delegation backs developing countries in WTO”. Peter Costantini, The Tear Gas Ministerial. December 3, 1999.

http://users.speakeasy.net/~peterc/wto/cuba.htm

“ENVIRONMENT-TRADE: Anti-WTO Protests Begin in Seattle”. Danielle Knight, Inter Press Service. December 4, 1999.

http://www.ipsnews.net/1999/12/environment-trade-anti-wto-protests-begin-in-seattle

“Trade talks without tear gas”. Peter Costantini, The Tear Gas Ministerial. January 17, 2000.

http://users.speakeasy.net/~peterc/wto/oped.htm

A skeptic’s roadmap of the WTO – November 2001

“What’s wrong with the WTO? A guide to where the mines are buried”. Peter Costantini. November 2001.

http://users.speakeasy.net/~peterc/wtow/index.htm

A reference site on the WTO treaties and issues surrounding them

The Tear Gas Ministerial Ten Years Later – December 2009

“TRADE: A Lost Decade for the WTO?” Peter Costantini, Inter Press Service. December 7, 2009.

http://www.ipsnews.net/2009/12/trade-a-lost-decade-for-the-wto

“Winners and losers: the human costs of ‘free’ trade.” Peter Costantini, Huffington Post. December 14, 2009.

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/winners-and-losers-the-hub_390651

Seattle, December 18, 2014

Since his college days, John Schmitt says, he’s been “very interested in questions of economic justice, economic inequality.” He served a nuts-and-bolts apprenticeship [...]]]>

Third article in a series on minimum wages. This is an expanded version of the interview published by Inter Press Service.

Seattle, December 18, 2014

Since his college days, John Schmitt says, he’s been “very interested in questions of economic justice, economic inequality.” He served a nuts-and-bolts apprenticeship in the engine room of the labor movement, doing research for several unions in support of organizing campaigns, negotiations and collective bargaining agreements. Now a broad-ranging theoretician with degrees from Princeton and the London School of Economics, his work continues to privilege

the needs and aspirations of working people. He’s an influential proponent of new approaches to research on low-wage work that have reoriented how much of the “dismal profession” and many policy-makers understand the issue.

Currently, Schmitt is a Senior Economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, DC. He also serves as visiting professor at the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, and was a Fulbright scholar at the Universidad Centroamericana "Jose Simeon Cañas" in San Salvador, El Salvador.

Inter Press Service interviewed him by telephone and e-mail between August and December 2014.

Minimum wages

IPS: Among policy prescriptions for reducing income inequality and lifting the floor of the labor market, where do you see minimum wages fitting in?

JS: I think the minimum wage is very important. It concretely raises wages for a lot of low and middle-income workers, but it also establishes the principle that we as a society can demand that the economy be responsive to social needs.

And that belief is really important. It’s just a legal, almost palpable statement that we have the right to demand of the economy that it serve us and not that we serve the economy.

So I think it’s very useful. It’s not the solution, in and of itself, to economic inequality. But it’s an important first step.

And it’s an easy first step. It’s something that we’ve had in this country since the 1930s. It’s something that has broad political support. It regularly polls way above 50 percent, even among Republicans. And in the population as a whole, the minimum wage is the kind of issue that 65 to 75 percent of voters support.

Of the last 3 increases in the [Federal] minimum wage, in 1990 – 91, in 1996 – 97, and then 2007 – 9, two were signed by Republican presidents, President Bush the First and President Bush the Second, with substantial support in all cases among Republicans in the House and Senate. So it’s a very American institution that has had a long history of bipartisan support.

And it’s effective in doing what it’s supposed to do, which is raise wages of workers at the bottom. One reason why it’s so heavily supported is because it does exactly what a lot of people think our social policy should do, which is reward people who work.

I think our social policy should go further than that. But almost everybody agrees that if you’re working hard, you should get paid a decent amount of money for that. And I think that’s why it enjoys such heavy support among Republicans as well.

Also, it doesn’t involve any government bureaucracy other than a relatively minor enforcement mechanism. Because everybody knows what the minimum wage is. There’s a social norm and a social expectation that people who work should get at least the minimum wage.

Therefore, it’s not quite self-enforcing, we definitely need enforcement and there are employers who violate the law. But it’s one of the easier social policies to enforce and to make sure it’s happening uniformly across the country.

Employment

IPS: One of main objections raised by opponents of minimum wage increases is that they reduce employment among low-wage workers. But beginning in the early 1990s, a new approach surfaced that challenged that contention.

JS: I was in graduate school then, right at beginning of what’s called the New Minimum Wage research. Basically, a lot of economists at the time were looking at the experience of states that had increased the minimum wage and were finding that state increases seemed to have little or no effect on employment.

Which ran in the face of both economic theory at the time, but also of some of the earlier empirical economic research that was not, I think, at the same standard of quality as subsequent research.

It caused a lot of controversy, and controversy is still raging. I think the profession has moved a lot towards the belief that moderate increases in the minimum wage, like the ones that we historically have done, have little or no impact on employment.

There was a big poll by the University of Chicago Business School in 2013 of 40 top economists who are regularly asked to comment on economic policy matters. They were asked about the minimum wage, and it was really striking to me.

They asked them two questions: one, would raising the wage to $9 an hour [which the President had recently proposed] significantly reduce the chances of less skilled workers and young people finding work? About a third of the respondents said they agreed, that it would reduce their chances of finding work, a third said they disagreed, and the rest had no opinion or weren’t sure. If you had done the same poll with the lead economists 30 years before, it probably would have been 2 to 1 saying that it would have a negative effect, or even more potentially.

But even more interesting was the second question: Given whatever you think about the employment effects, do you still think it would be a good idea to raise the minimum wage to $9 an hour? And there it was something like 5 to 1 in favor of increasing the minimum wage.

So I think that there’s a recognition within the economics profession that, even if there are job losses associated with moderate increases in the minimum wage, that they’re very small relative to the wage increases for the vast majority of people who will keep their jobs. I think that’s increasingly the standard view within the profession.

Now, that doesn’t mean that the bulk of the economics profession thinks that the minimum wage should be $15 an hour or $25 an hour. But it does suggest that even the economics profession is seeing this issue in I think a more realistic way.

The textbook model for how the labor market works is just a vast oversimplification. It can be useful in some contexts, but it’s just not useful to understand a pretty complicated thing, which is what happens when the minimum wage goes up.

Data and models

IPS: Is this mainly a new economic model replacing old ones, or is it just looking more accurately at the actual statistics from what’s happened.

JS: I think it’s some sort of combination of both things.

I think the first thing is that what most economists are persuaded by is just that the empirical evidence is not that supportive of large job losses. And whatever the theoretical explanation, we can put that aside for a second. There’s just a lot of good research out there that consistently finds little or no negative employment effects. And when that just happens again and again in the research, I think that wears away economists’ views about a particular result, in the textbook competitive model.

We have 25 years of people who have very high standing in the profession, who have PhD’s from prestigious programs and they teach at prestigious places and publish in prestigious journals. And they’re consistently finding with very good research, very little effect [on employment]. I think that changes the way people think about this issue.

And then the question is: Why is that? And there has been a lot of research and thinking about the labor market and the way it works that is consistent with the results they’re finding.

For example, a recent Nobel Prize was given for 3 economists who had worked heavily in an area called “search models” of the labor market.

And one of the fundamental issues of search models is that, unlike the competitive model, where firms and employers and workers can very easily match and find each other, that in fact, search is costly, that it’s hard for firms, even when labor markets are working fairly well, to find employees, it’s hard for employees to find the right match, that people receive offers and reject them and that things go back and forth. Firms have workers that could work for them, but they don’t hire them for whatever reason.

So that’s one set of issues. The other area that has also been recognized with Nobel Prizes has to do with information problems within markets. That employers don’t know exactly how an employee is going to perform until they hire them, how well their skills match their resume. They don’t know their work attitude. And employees have information that employers don’t know about how hard they’re willing to work. And it can be hard to persuade people until you actually show up that you really are going to work as hard as you say.

So that’s another issue with information, it’s a crucial part of the whole rethinking of the labor market. And that’s a key issue within what’s happening with the minimum wage.

Not all workers or potential workers know of every job they can see that’s in the area, and not all employers know of every single person that’s looking for a job. So the matching can be slow and painful and costly. And one of the key insights [is] that employers aren’t operating in a competitive labor market nor are employees.

But I think within the mainstream economics profession there are a lot of other potential explanations that also fit. There’s the possibility that employers make adjustments in other dimensions besides laying workers off: they raise their prices somewhat, or they cut back on hours but don’t lay off workers.

And from a worker’s point of view, if they raise your salary by 20 percent and they cut your hours by 5 or 10 percent you’re still better off, right? Because you’re getting paid more money and you’re working fewer hours.

That might not be the employers’ favorite thing to do, but it certainly works well for workers. So there are a lot of ways that firms can adjust to minimum wage increases other than laying people off.

Turnover

IPS: So from a worker’s point of view, even if there were a reduction in hours or more unemployment, I still come out ahead. Low-income work is already very unstable. Hours are variable and often part-time, and there are a lot of layoffs, firings and quitting.

JS: Some of the best research is on the simple question of turnover – which is an important ingredient here, labor turnover. There’s a new paper by Arin Dube, Bill Lester and Michael Reich [three U.S. economists]. Basically, they look very carefully at what happens to labor turnover rates before and after minimum wage increases, and find substantial declines in turnover for different kinds of workers.

One concrete example from a different study: there was a living wage law that was passed at the San Francisco airport a few years back, and they did an analysis of what happened to the workers that were affected. And they found something like an 80 percent decline in turnover of the baggage handlers after the minimum wage went up, the living wage. And there were substantial increases in wages for those workers.

I think that’s probably on the high end of what you could expect. But even reductions of 20, 25, 30 percent in a high-turnover industry, it makes a big difference.

Something that I think people who don’t work in business don’t fully appreciate is that turnover is extremely expensive, even for low-wage workers. Filling a vacancy for a low-wage job can be 15, up to 20 percent, of the annual cost of that job. That sounds a little bit high, but if you stop to think about it, it makes a lot of sense.

One issue is that when you have a vacancy, the people who have to fill it are managers. So they have to use their time, which bills much more expensively than low-wage workers, to fill that. They need to post an ad, they need to review the resumes that are handed in, then they need to interview people, then they need to spend time training that person and integrating them into the company. That can take weeks of time to do, and it’s weeks of time at a manager’s billing rate, not at the low-wage worker’s billing rate.

And meanwhile, while the vacancy is there, you’re losing customers, because people come in and they see that there’s a long line, so they go next door.

And then the other thing is once you have a new worker, even if it’s a fast food worker that has experience working at McDonald’s, now they’re working at a Burger King, and they do the systems differently. You have to learn the new way to do that. Even if you’re at a slightly differentMcDonald’s, the one you worked at was a suburban McDonald’s that had a drive-through, now you’re working at a downtown McDonald’s and they have a different way of doing things. You’re not going to be as efficient, you’re not going to be as integrated into the team for a while.

So there’s a lot of cost of turnover. And if the minimum wage reduces turnover, which there seems to be an increasing amount of evidence that that’s the case, then it can go a long way towards explaining why we see so little employment impact of minimum wage increases. And I think that’s what’s going on.

Mitigation

IPS: What other factors mitigate the employment effects of minimum wage increases in different localities?

JS: It’s hard to compare. It’s not just the size of the increase; it’s how many workers are affected by that increase, and how much is average increase is relative to how much they’re getting paid right now.

So at the Federal level, when the minimum wage goes up by say 15 percent in a year, the average wage increase for workers who are affected by that is much less than 15 percent. It’s half of that. And for some increases it could be even less than that, because not everyone gets the full increase. It also depends on where the starting wage is.

And keep in mind also, every single business that’s operating in Seattle, or Santa Fe, or the State of California, or wherever they’re going to do an increase, is operating under same rules.

And for the most part, businesses that are involved heavily in the low-wage labor market and are affected by the minimum wage are ones that are competing very much at a local level. It’s retail, it’s fast-food restaurants, it’s full-service restaurants, dry cleaners, and the low-wage service sector, that’s really what we’re talking about here. So you’re not putting any company at any competitive disadvantage relative to the vast majority of their competitors.

Part of what‘s going to happen is that there will be efficiency gains. The best companies, the best managed companies, the ones who know how to operate effectively with higher wages, are going to take over the market share.

So it might be that some business goes out of business, but the people who eat sandwiches there are now going to be buying sandwiches from the same shop under a different name, or they’re going to be buying from the shop next door where the manager knows how to get workers to be productive and effective at the new wage, relative to the other manager who wasn’t able to do that.

Velocity

IPS: What about the velocity of adjustment?

JS: A lot of initial studies, especially the early studies from the New Minimum Wage Research, looked at relatively short periods of time, 6 months or a year after the minimum wage. And so they were criticized for not looking long enough. And now I’d say most their research looks for a year, and then two and even three years.

My view is that to the extent that these are going to have impacts on prices or employment, you’re going to see them pretty quickly. And the reason why you’d see them quickly in employment is because it’s a very high turnover area.

So say you have a fast food restaurant and you have 30 employees, 30 openings where you have workers. In the course of a year, you might have 60 workers who fill those 30 slots. And imagine that the critics of the minimum wage are right, and instead of having 30 employees, now because of the minimum wage increase now you’re only going to have 28.

Well, basically, in a month, two people are going to leave and you’re just not going to fill those slots. So it’s just going to come up very quickly. If you really can’t afford to pay 30 workers, two of them are going to leave because they go to college, because one of them has a baby and decides to stay home, because their spouse moved to another state and they’re following their spouse. Any number of things happen. They hate the job so they quit. And it’s very much more likely to happen in low-wage jobs.

So you immediately adjust at 28, assuming that that’s correct.

Similarly, it’s not that hard to change prices. If this means you’re going to have to raise your prices by 3 percent or 4 percent, you change the prices. It’s not like it takes 6 months to change a price. I mean, you basically change your menu and then you’re done. It just doesn’t take too long for the adjustments to take place.

Teenagers

IPS: Some of the earlier minimum-wage research seems to have focused mainly on teenagers. But teenagers are 12% now of the total low-wage workers. And even in 1979 they were only 26%.

JS: I think that there’s a longstanding focus on teenagers that goes back 50, 60 years, possibly longer, in research on the minimum wage.

And the reason is because economists want to see if they can find negative results. You want to look for the canary in the coal mine; you want to look for the most sensitive group that you can identify. And if you find negative results there, you can say “Look, we found negative results. And we have reason to believe that the same kind of dynamic, less intensely, is going to be operating on slightly older workers and on adult workers.”

The flip side of it is, if you look at teenagers and you don’t find any employment loss among teenagers, who ought to be the most sensitive to rate increases in the minimum wage, it seems very unlikely that you’re going to find them anywhere else.

And then of course another area where people look a lot is not at workers themselves, but at employment in other industries such as fast food and retail where there are a lot of low-wage workers.

I think we now have a lot of evidence, looking at a lot of ways to cut the data, that all point towards little to no employment losses for moderate increases.

The thing about it is, even though most of the workers who earn at or near the minimum wage are not teenagers, you’re looking for a group that is very heavily concentrated in the low-wage sector. So it’s just easier to find an effect.

From my point of view, I’m fine with the framing of looking at teenagers or looking at fast food. Because what consistently is the case is that they’re not finding any negative results even there.

So if it were the case that they were finding employment losses for teenagers, then I think we could have an argument about whether or not that was generalizable to the rest of the population. But I think at this point we’re not having even that argument particularly strongly.

The thing that’s interesting to me is that it’s often framed that, “This is going to hurt African-American and Latino kids, young teenagers.” And what’s striking to me is that the implied impacts on African-American and Latino teenagers, even if you belief the harshest critics of the minimum wage, are tiny compared with the permanent gaps in employment between African-American and Latino teenagers on the one hand and white teenagers on the other hand.

And yet, when we’re not talking about the minimum wage, the same people who are crying tears about black teens are doing absolutely nothing to address the permanent long-term gap in employment between black teens and white teens, whenever the minimum wage isn’t on the table. It’s always there and it’s not related to the minimum wage in any way. And there’s no concern about “Let’s address this tragedy”, except in the context of preventing the minimum wage from going up.

Earned Income Tax Credit

IPS: What about the Earned Income-Tax Credit? [A provision of the U.S. income tax code that subsidizes lower-income working families according to the number of their children] It seems that some mainly conservative commentators have opposed that to the minimum wage.

JS: The Earned Income Tax Credit and the minimum wage I think are strongly complementary policies. And to suggest that one is a substitute for the other is to miss the way that they both work.

I am always concerned when I hear conservatives criticizing the min wage, and offering the EITC instead. Because that’s used to beat down the minimum wage. But when the tough vote then comes to increase the EITC, because that’s what we should be doing, they’re suddenly concerned that, well, this is a tax increase, it increases the size and role of the federal government in the economy, and therefore we shouldn’t do it. So all of these other ideological reasons to oppose the EITC come to the fore when the minimum wage isn’t on the table.

But basically, the way the EITC is structured, it lowers wages for employers, and in fact what that means is that they capture some important part of the tax dollars that are used to expand the EITC.

Which is not the intention: the intention is that the money go to low-wage workers themselves, not their employers. And because of the way the EITC is structured, it lowers wages and the employers actually capture an important part of the benefits.

There’s a very good study by an economist at Berkeley, Jesse Rothstein, who estimates that about 27 cents of every dollar that we spend on the EITC actually goes to benefit employers rather than the workers who are supposed to be getting it.

Because basically, the EITC raises the after-EITC wage of many workers who get it, but that increases the supply of workers to the labor market. And that in turn reduces the market wage of workers, because there are more workers out there.

If you get the EITC, you’re still coming out ahead. But the point is the market wage has fallen, which from the employers’ point of view means they’re paying less for the workers that they get. And they actually therefore capture a part of the increase, and it’s not a small part, it’s about a fourth of the total expenditure.

Now what the minimum wage can do is it can limit the ability of employers to capture that because it puts a floor on the wage. And it prevents the wage from falling too low and it prevents employers from capturing the EITC in the form of lower wages. So they work well together as policies.

Democracy

IPS: What about Santa Fe? [A city in New Mexico that raised its minimum wage 65% in 2004, the biggest recent local increase] You’ve done a study on it.

JS: I would not want to make too much of any one case, whether it’s New Jersey versus Pennsylvania back in the early 90s that led to the David Card and Alan Krueger study [that began the New Minimum Wage research], or a specific issue of Santa Fe or

Albuquerque more recently or San Francisco.

No two cities are exactly alike. But I think the evidence is mounting up that a lot of different cities or states in a lot of different contexts raise the minimum wage and we don’t see big effects.

When Santa Fe decided to raise the minimum wage, it was a very big increase. But I have a lot of faith in the democratic process. So when you have a city that’s focused on where should we set the wage, a lot of people weigh in: business people in the community weigh in, workers in the community, unions in the community, community organizations dealing with social service questions. and low wage workers who are struggling to make ends meet, academics from local universities who know the economy and the social situation well.

There’s a city-wide or a state-wide conversation. And that process – and I think this is one reason why we consistently don’t see big employment effects – usually arrives at some wage that is a vast improvement over what we currently have and within the realm of what the local economy can afford.

An important reason why we don’t see job losses is because the people who have the biggest voice in this are business. They understand politically that they have to get in, but they’re going to push back as hard as they can. I think we probably consistently err on the side of caution rather than on the side of going too far.

So what’s interesting about Santa Fe – or we just passed a minimum wage bill here in the City Council in Washington, DC – is that a lot of people weighed in. I was one of well over 100 people who testified before the City Council with their opinion. There were people from National Restaurant Association and the Chamber of Commerce, unions, small business organizations, academics, policy people.

And the City Council heard, and they were choosing between a bunch of different proposals, and they hammered out a proposal that worked.

It sounds like in Seattle there was a very similar process. It was shooting towards 15 dollars, but then there was a consideration of how we get there exactly, how fast we get there, who gets there how fast, are there any exemptions. I have a lot of confidence that what happened in Seattle will work well, because so many factors were taken into consideration in the process of setting those wages.

Labor

IPS: How do you see the 15Now movement, the fast-food workers movement, changing the labor movement?

JS: I think it’s very encouraging. There’s a lot of dynamism behind the fast food and 15 folks and what’s happening in Seattle, a lot of city and state campaigns to increase the minimum wage. They’re putting a lot of focus on wages and wage inequality, and the need to reward people for working hard.

They’re also focusing attention on a couple of other issues that are going to be really important in the future, I think they’re going to be increasingly a part of the public debate: for example, around scheduling questions. One of the recurring problems for fast-food workers and retail workers is not just that their wages are so low, but also that they have little or no control over their schedules. And that’s an issue that goes way above people who are making $7.25 or $10 or $15 an hour.

And in particular, in the absence of private sector unions that can help protect workers against scheduling problems, that’s going to be an increasing concern to have legislation, but also to have some kind of worker voice on the job that can help address those things.

I think any time you have people agitating for economic and social justice and getting national attention while they’re doing that, it’s encouraging for the possibility of turning around 3 going on 4 decades of rising economic inequality.

I’m encouraged by the moment that we’re living right now on this front. The single most important thing is to keep some oxygen flowing here so that this conversation can continue to happen: the media cover it, people talk about it when they’re having a beer with their friends, or when they’re walking around downtown at noon and they see a bunch of McDonald’s workers out making noise. That’s not something we’ve seen a lot of in the last 35 years.

[Edited for length and clarity. See newswire article on Inter Press Service – link]

More on John Schmitt

Publications

“Why Does the Minimum Wage Have No Discernible Effect on Employment?” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, February 2013. http://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/min-wage-2013-02.pdf

“The Minimum Wage Is Too Damn Low”. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, March 2012. http://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/min-wage1-2012-03.pdf

With Janelle Jones. “The Wage and Employment Impact of Minimum-Wage Laws in Three Cities”. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, March 2011. http://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/min-wage-2011-03.pdf

With David Rosnick. “Low-wage Workers Are Older and Better Educated than Ever”. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, April 2012. http://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/min-wage3-2012-04.pdf

Full list: http://www.cepr.net/index.php/clips/john-schmitts-publications

Biography

http://www.cepr.net/index.php/experts/biographies/john-schmitt

Related articles in minimum wage series

Peter Costantini. “Low-Wage Workers Butt Heads with 21st Century Capital”. Seattle, WA: Inter Press Service, June 3, 2014. http://www.ipsnews.net/2014/06/low-wage-workers-butt-heads-with-21st-century-capital/

Expanded version on blog. http://www.ips.org/blog/ips/low-wage-workers-butt-heads-with-21st-century-capital

Peter Costantini. “Minimum Wage, Minimum Cost”. Seattle, WA: Inter Press Service, August 11, 2014. http://www.ipsnews.net/2014/08/minimum-wage-minimum-cost

Expanded version on blog. http://www.ips.org/blog/ips/minimum-wage-minimum-cost

Second article in a series on minimum wages.

Note: This is an expanded, footnoted version of the article published by Inter Press Service.

In 1958, when New York State was considering raising its minimum wage 33% from $0.75 to $1.00, merchants at hearings complained that their profit margins were so small that [...]]]>

Seattle

Second article in a series on minimum wages.

Note: This is an expanded, footnoted version of the article published by Inter Press Service.

In 1958, when New York State was considering raising its minimum wage 33% from $0.75 to $1.00, merchants at hearings complained that their profit margins were so small that the increase would force them to cut their work forces or go out of business.[1] In Seattle in 2014 at hearings on a proposed 61% minimum wage increase from $9.32 to $15.00, some businesses voiced the same fears.

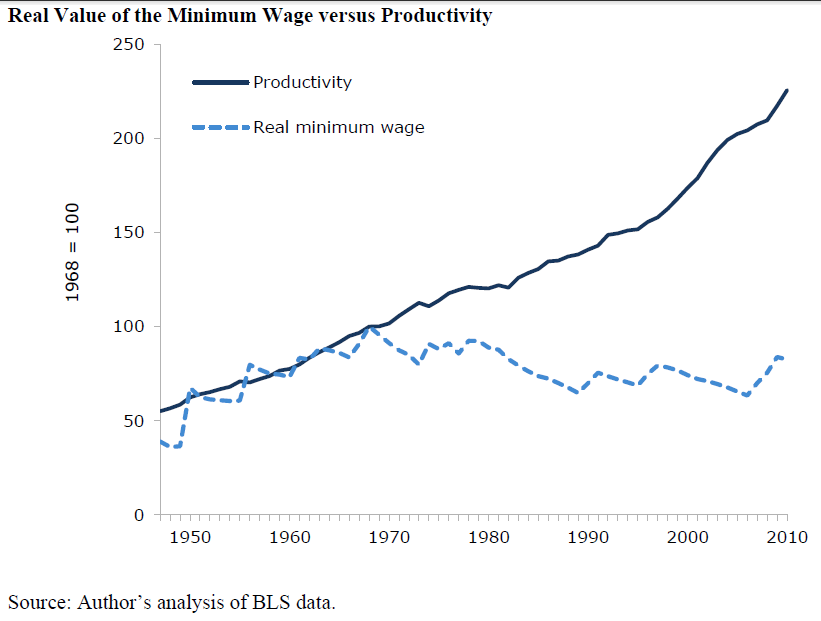

A national minimum wage was established in the United States in 1938 by the Fair Labor Standards Act. Since then, Congress has increased it every few years, although since 1968 it has fallen far behind inflation and productivity growth.

By 2015, over half of the states[2] and many localities will have increased local minimum wages above the federal level. Several major cities, including New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland (California) and San Diego (California), are currently considering raising their wage floors.[3]

Each time such raises are proposed, bitter debates break out over the potential effects. Somehow, though, economic devastation has been repeatedly averted.

History

Historically, the yearly average for recent local minimum wage increases has been 16.7%.[4] But some increases have been far higher. For example, in 1950 the national minimum wage jumped 87.5% from $0.40 to $0.75. And in 2004, the city of Santa Fe, New Mexico, raised its minimum from $5.15 to $8.50, a 65.0% increase.

Even after Santa Fe’s big raise, the average cost increase for all businesses caused by the raise was around one percent. For restaurants, the increase was a little above three percent.[5] The effects may have been so small in part because Santa Fe may have had an unusually low percentage of workers earning close to the old minimum wage.[6]

Santa Fe’s Mayor, David Coss, summed up the experience: “I am proud of Santa Fe’s living wage law. I am also very proud of the businesses in Santa Fe who pay a living wage. Our work on the living wage has made Santa Fe a national leader and has strengthened our economy, community and working families.”[7]

Accounting

The small impact of raising the wage floor may be surprising to those unfamiliar with the historical record. But the accounting is straightforward. Nationally, only 4.3% of all workers earn the federal minimum wage or lower; perhaps two or three times that number would have their wages lifted by a moderate minimum wage hike. All the rest of the workforce would not be affected by the increase.[8]

Among those covered, the average raise will be somewhere around half of the nominal raise from old to new minimum, because most affected workers will have wages somewhere in between. As a result, the total growth in payroll is small for most businesses. And payroll, in turn, averages only about one-sixth of gross revenues for all industries nationally.[9]

These effects, multiplied together, yield very small total increases in costs on the average and for the great majority of businesses.

Employment

Because total cost increases are minimal for most businesses – even in more-affected industries – and can be covered by other adjustments, the loss of low-wage jobs because of moderate minimum wage raises’ has been close to zero. The broad consensus that has emerged from the evidence is that they have no significant effects on employment.[10]

Over the past two decades, the results on the ground of national, state and local increases have been studied intensively using empirical methods that control for other possible influences.

A comprehensive study of state minimum wage increases in the U.S. found “no detectable employment losses from the kind of minimum wage increases we have seen in the United States”, including for the accommodations and food services sector.[11] Two recent meta-studies that analyzed the past two decades of research seconded these findings.[12] Other rigorous economic examinations of minimum wage increases in cities including Santa Fe, San Francisco and San Jose also found no discernable negative effects on employment for low-wage workers.[13]

A study by economists John Schmitt and David Rosnick of the Center for Economic and Policy Research concluded: “The results for fast food, food services, retail, and low-wage establishments in San Francisco and Santa Fe support the view that a citywide minimum wages can raise the earnings of low-wage workers, without a discernible impact on their employment. Moreover, the lack of an employment response held for three full years after the implementation of the measures, allaying concerns that the shorter time periods examined in some of the earlier research on the minimum wage was not long enough to capture the true disemployment effects.”[14]

As Harvard economist Richard Freeman put it, “The debate is over whether modest minimum wage increases have ‘no’ employment effect, modest positive effects, or small negative effects. It is not about whether or not there are large negative effects.”[15]

A letter to the President and Congress signed by 600 economists, including seven Nobel Prize winners, supported raising the national minimum wage to $10.10: “In recent years there have been important developments in the academic literature on the effect of increases in the minimum wage on employment, with the weight of evidence now showing that increases in the minimum wage have had little or no negative effect on the employment of minimum-wage workers, even during times of weakness in the labor market. Research suggests that a minimum-wage increase could have a small stimulative effect on the economy as low-wage workers spend their additional earnings, raising demand and job growth, and providing some help on the jobs front.”[16]

Even The Economist, the influential British neoliberal magazine, recently observed: “No-one who has studied the effects of Britain’s minimum wage now thinks it has raised unemployment.”[17]

Income

In worst cases, some employers may face larger increases in payroll than they can absorb with price increases and increased efficiencies. But even for them, the response will much more likely be to reduce hours slightly than to cut jobs, because laying off and hiring are expensive and disruptive.[18] In such cases, any increase in wages large enough to prompt a reduction in hours would likely be big enough that the paychecks of workers receiving it would still come out ahead.[19]

In many low-wage jobs, hours already fluctuate from week to week, workers frequently change jobs voluntarily or involuntarily, jobs come and go, and businesses start up and fold. For low-wage workers already facing this instability, higher total yearly pay nearly always trumps any loss of yearly hours. In fact, working fewer hours can be a benefit in this case, as it leaves more time for family, training or other work.[20]

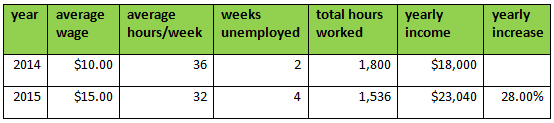

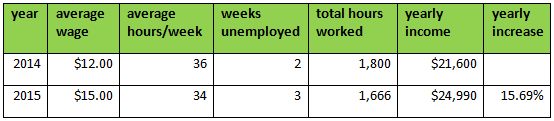

For low-wage workers, employment effects show up primarily in average hours worked weekly and total time out of work yearly. As a hypothetical case, if my hourly wage goes up 50% from $10.00 to $15.00, but my average weekly hours worked drop from 36 to 32 and I’m out of work for 4 weeks instead of 2 weeks, I’m still considerably ahead of the game with a 28.0% increase in my yearly income. If I qualify for unemployment insurance for the weeks out of work, my situation is even better.

Alternatively, let’s say I’m making $12.00 when my wage rises to $15.00, a 25% increase. Assuming my average weekly hours worked drop from 36 to 34 and I’m out of work for 3 weeks instead of 2 weeks, my yearly income would still be 15.69% higher.

These examples intentionally use improbably large reductions in hours and increases in unemployment, despite strong evidence that cities that have implemented substantial wage increases have seen no significant employment effects.

Ripples

Minimum wage increases do have the effect of compressing the lower part of the pay scale. Those who were making around the old minimum will now be making nearly the same as those who were making near the new minimum. The differences between the lower rungs of the wage ladder will now be much diminished, which may prompt changes in business processes and work relationships.[21]

In this situation, most businesses try to maintain some hierarchy, with the new minimum pushing up the wage levels just above it by small amounts. But this “ripple effect” of small cascading raises adds only a little to total payroll costs.[22] For a 1997 increase of 8% in the federal minimum from $4.75 to $5.15, one study found that workers who had been earning just above the new minimum got a 2% increase (roughly $0.10), and those up to about 10% above the new minimum got a 1% increase (roughly $0.05).[23]

The same study also found that a 2004 increase of 19.4% in the Florida state minimum caused an average cost increase for businesses, from both mandated raises and ripple effects, of less than one-half of 1% of sales revenues. For the hotel and restaurant industry, the average cost increase was less than 1.0%.[24]

The size of ripple raises will depend in part on how important maintaining wage-level distinctions is to employees and employers. It will also be affected by competition from the rest of the low-wage labor market.

Raising the wage floor generally rewards businesses who already pay higher wages towards the bottom of the scale, because minimum wage increases will be a smaller percentage of costs for them. So even contemplating minimum wage legislation could offer incentives to employers to maintain less unequal wage scales.

Exceptions

Only one sector has significantly higher concentrations of low-wage workers and a larger proportion of expenses in payroll: accommodations and food services. It is not a major part of the economy in most places: nationally it accounts for 2.2% of sales, 3.6% of payroll and 10.8% of employment.[25] In these industries, 29.4% of workers are paid within 10% of the minimum wage,[26] and the rule of thumb for restaurant payroll is about one-third of total revenues, twice the overall proportion.

Even for hotels and restaurants, however, larger rises in operating costs are still covered mainly by modest price increases, on the order of 3.2% for a 50% minimum raise by one estimate, and significant reductions in turnover, ranging between 10% and 25% of the costs of raising the wage.[27] Many businesses in this sector have enough flexibility to raise prices without reducing revenues, especially when local competitors all face the same wage increases.[28] They may also be able to raise revenues by increasing sales volume.

In retail, another sector employing some low-wage workers, only 8.8% of the workforce is paid within 10% of the minimum wage.[29] So any minimum wage increase has a much smaller effect on average total costs than in the lodging and food service sector.

Adjustments

In all sectors, lower-wage workers tend to have higher turnover rates, sometimes more than 100 percent annually, yet firing and hiring entail significant costs.[30] Minimum wage increases often help trim these personnel expenses by reducing workforce turnover and absenteeism.[31] The savings, by one estimate, may range from 10% to 25% of the increased payroll costs from raising the minimum.[32]

Businesses may also gain from better-paid and more secure workers becoming more productive. Improvements in business processes and automation can lower expenses and increase quality. And better performance may be required of employees who are now paid higher.[33]

Other possible channels through which businesses can compensate for payroll growth include reductions in benefits or training, changes in employment composition, improvements in efficiency and automation of work processes. Some employers may also accept a small reduction in profits until the wage increases are absorbed.[34]

Even given these multiple channels for adjustment, there are often small businesses and non-profits who find it hard to cover a minimum wage increase – often because they depend heavily on low-wage labor or are unable to raise prices easily. In recognition of this, most local minimum wage increases either exempt smaller firms and non-profits, as in Santa Fe and San Francisco, or phase in increases more slowly for them, as in Seattle.

Stimulus

In the broader economy as well, raising the wage floor may have positive effects. Increased spending prompted by higher wages can stimulate growth in low-wage workers’ neighborhoods.[35]

Rising minimum wages also often reduce government spending on low-income tax credits and poverty programs such as food stamps. Contributions to unemployment insurance, Social Security and Medicare rise with higher incomes. Any positive or negative effects, though, will tend to be small-scale relative to the overall economy.

Given the major positives for low-wage workers and society at large, along with the relatively minor negatives, it is not surprising that nearly all groups with a track record of advocacy for these workers, such as unions, low-income community groups and non-profits serving them, support minimum wage increases.

In an era of secular stagnation and political stalemate, minimum wage increases offer an effective, politically popular, and positively motivating way to reduce income inequality from the bottom up, without reducing low-wage employment.

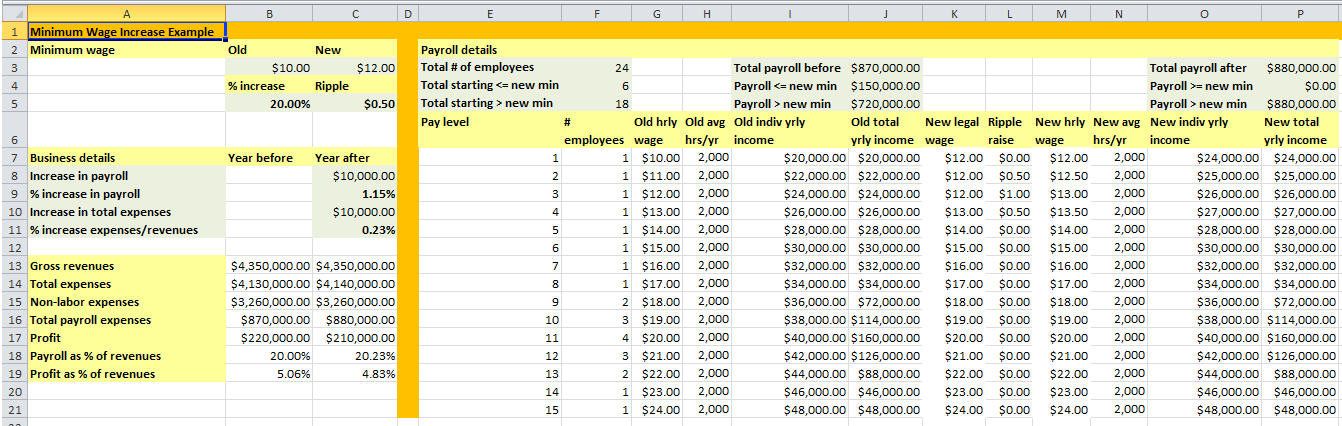

Example: Crunching the numbers for a small business

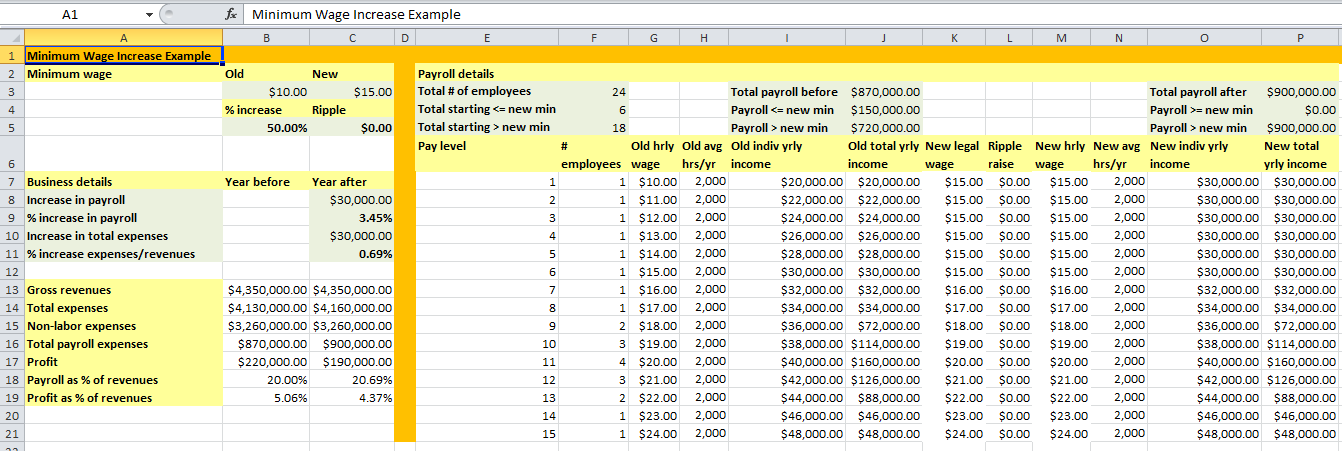

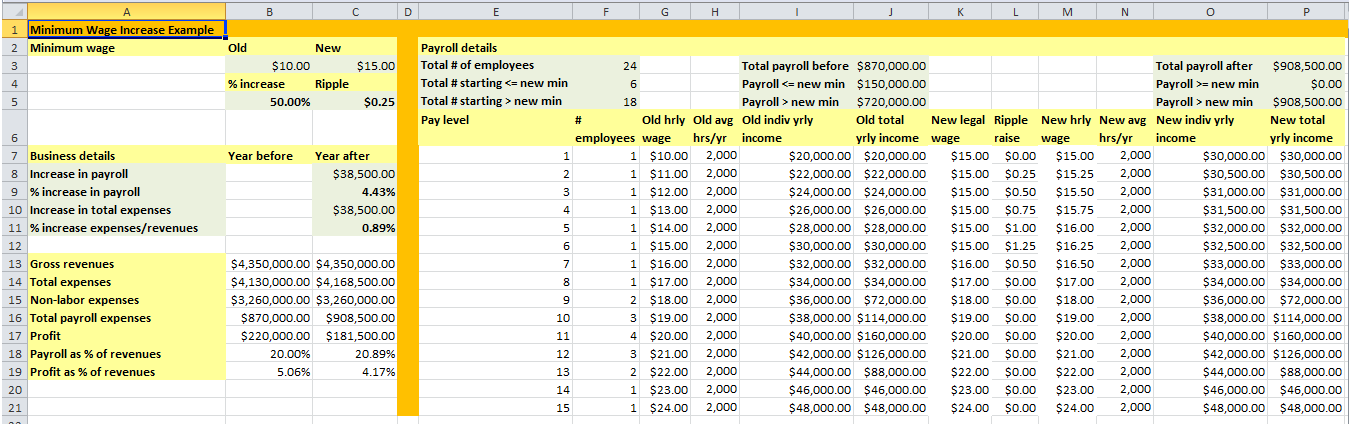

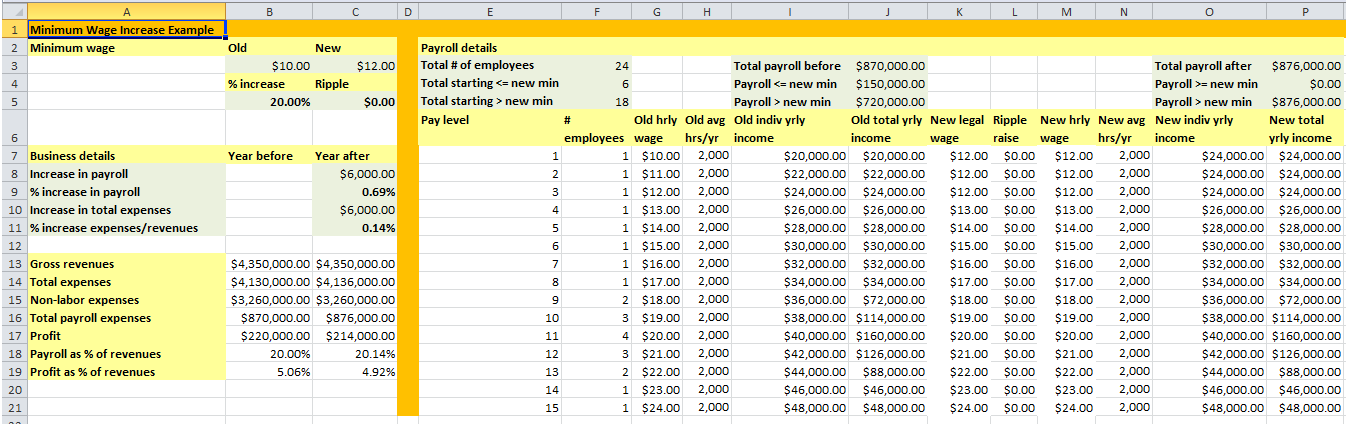

To get a concrete sense of how raising the wage floor plays out, a little arithmetic goes a long way. Let’s take a hypothetical example of a big raise of 50% in one year, from $10.00 to $15.00.

We’ll zoom in from macro to micro and crunch some simplified numbers for a typical small business that employs 24 workers. Six of them make below or equal to the new minimum: one each makes $10.00, $11.00, $12.00, $13.00, $14.00, and $15.00. The other 18 employees make an average wage of $20.00, and all workers work 2,000 hours per year. The total payroll of this company is 20% of its gross revenues and its profits are 5%.

The average pre-increase wage of the five workers getting a raise is $12.00 per hour, $10.00 through $14.00 divided by five, and their average raise is $3.00. This computes to a 25% – not 50% – average raise for the five covered workers. For the total payroll, this represents an increase of 3.45 percent.

The total impact of a minimum wage increase of 50% on this hypothetical business, then, is to raise its total expenses 0.69% of gross revenues, or less than one percent.

Nationally across all industries, the proportion of payroll to gross revenues is smaller, 16.8 percent[36] rather than 20 percent. And most yearly minimum wage increases have been far less than 50% – an average of 16.7% yearly for local ordinances[37] – so the percentage of affected workers would probably be closer to 10%[38] than 25%. Rounding up, for a 20.0% nominal minimum increase to $12.00 for the same sample payroll, the average for the two workers receiving raises will be 14.3%, yielding a rise in total payroll of 0.69% and in total expenses of 0.14% of gross revenues.

If we factor a ripple effect into our 50%-raise example, spillover wages that keep at least a $0.25 differential between the new levels – $15.00, $15.25, $15.50, etc. – would raise the total payroll increase from 3.23% to 4.43%, and the total increase in business expenses over revenues from 0.69 to 0.89% of gross revenues.

Applying a $0.50 ripple differential to a 20% minimum wage increase for the same data, the total payroll increase would be 1.15% and the total expenses increase would be 0.23% of revenues. We use a lower ripple for the bigger increase because ripple effects tend to be smaller for larger minimum wage increases.[39]

These examples do not take into account many factors such as taxes or benefits. But none of these would appreciably change the big picture of very small cost increases for an average business.

Download zip file of Excel spreadsheets with four examples.

Endnotes

[1] AP 11/19/1956

[2] NELP – What’s the Minimum Wage in Your State?

[3] NELP 5/28/2014. City News Service 4/23/2014.

[4] Reich, Jacobs & Bernhart 3/20/2014, Table 3

[5] Pollin et al

[6] Reich, Jacobs & Bernhart 3/20/2014. Schmitt & Rosnick 3/2011, pp. 28 -30. Potter 8/23/2006. Potter 6/30/2006.

[7] CEPR, 3/22/2011

[8] 23.6% of Seattle workers between $9.32 and $15.00 (60.9% increase) – Klawitter et al. For an increase of 20%, only 7.9% if distribution uniform. Raised estimate to 10 – 12% because Seattle has higher than average wages for U.S. and distribution may be skewed to lower side. Only 4.3% of US workers make the minimum wage – BLS 3/2014.

[9] US Census Bureau 2012, Table 756. Author’s calculation: 16.8%.

[10] Dube, Lester & Reich 11/2010. Schmitt 2/2013.

[11] Dube, Lester & Reich 11/2010, p. 961 – 962

[12] Reich, Jacobs & Bernhart 3/20/2014. Schmitt 2/2013.

[13] Reich 10/2012. San Jose. Schmitt & Rosnick 3/2011. San Francisco & Santa Fe

[14] Schmitt & Rosnick 3/2011

[15] Freeman 1995

[16] Economic Policy Institute 2014

[17] J.P.P (The Economist) 5/3/2014

[18] Schmitt 2/2013, p. 15

[19] Schmitt 2/2013, pp. 17 – 18. Pollin et al 2008, pp. 231 – 232.

[20] Schmitt 2/2013, pp. 17 – 18. Pollin et al 2008, pp. 231 – 232.

[21]

Wicks-Lim 7/2012

[22]

Reich 10/2012. San Jose.

[23] Wicks-Lim 5/2006

[24] Wicks-Lim 5/2006

[25] US Census Bureau 2012, Table 756

[26] Dube, Lester & Reich 11/2010, p. 961

[27] Wicks-Lim 7/2012

[28] Wicks-Lim 7/2012

[29] Dube, Lester & Reich 11/2010, p. 961

[30] Reich 10/2012, p. 8. Boushey & Glynn 11/16/2012. Hirsch, Kaufman & Zelenska 11/2013, pp. 31 – 32.

[31] Wicks-Lim 7/2012. Schmitt 2/2013. Dube, Lester & Reich 7/20/2013, p. 3. Reich, Hall & Jacobs 3/2013.

[32] Wicks-Lim 7/2012

[33] Wicks-Lim 7/2012. Schmitt 2/2013. Hirsch, Kaufman & Zelenska 11/2013.

[34] Schmitt 2/2013. Reich, Jacobs & Bernhart 3/20/2014.

[35] Economic Policy Institute 2014. Reich, Jacobs & Bernhart 3/20/2014, p. 16.

[36] US Census Bureau 2012, Table 756 – author’s calculations

[37] Reich, Jacobs & Bernhart 3/20/2014

[38] 23.6% of Seattle workers between $9.32 and $15.00 (60.9% increase) – Klawitter et al. For an increase of 20%, only 7.9% if distribution uniform. Raised estimate to 10 – 12% because Seattle has higher than average wages for U.S. and distribution may be skewed to lower side.

[39] Wicks-Lim 7/2012

References

Associated Press. “Plan for $1 hourly State Minimum Wage Is Under Attack by Retailers at Hearing”. New York: New York Times, November 19, 1956. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=9805E3D6143BE13BBC4851DFB767838D649EDE

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Characteristics of Minimum Wage Workers 2013”. Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics, March 2014. http://www.bls.gov/cps/minwage2013.pdf

City News Service. “Ballot Measure Would Raise San Diego Minimum Wage To $13”. San Diego, CA: KPBS Public Broadcasting, April 23, 2014. http://www.kpbs.org/news/2014/apr/23/san-diego-council-president-proposes-raising-minim/

Arindrajit Dube, T. William Lester, & Michael Reich. “Minimum Wage Effects Across State Borders: Estimates Using Contiguous Counties”. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Review of Economics and Statistics, November 2010. http://www.irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/157-07.pdf

Economic Policy Institute. “Over 600 Economists Sign Letter In Support of $10.10 Minimum Wage”. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute, 2014. http://www.epi.org/minimum-wage-statement/

Richard Freeman. “What Will a 10% … 50% … 100% Increase in the Minimum Wage Do?”. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 48 (4), 1995. Pp. 830-34.

J.P.P. “The minimum wage: What you didn’t miss”. Washington, DC: The Economist, May 3, 2014. http://www.economist.com/blogs/democracyinamerica/2014/05/minimum-wage

Marieka M. Klawitter, Mark C. Long & Robert D. Plotnick. “Who Would be Affected by an Increase in Seattle’s Minimum Wage?”. Seattle, WA: City of Seattle, Income Inequality Advisory Committee, March 21, 2014. http://www.seattle.gov/council/issues/minimumwage/attachments/UW%20IIACreport.pdf

National Employment Law Project. “What’s the Minimum Wage in Your State?”. New York: National Employment Law Project, accessed July 27, 2014. http://www.raisetheminimumwage.org/pages/minimum-wage-state

National Employment Law Project. “Following Historic Seattle Agreement, Chicago Becomes Next City to Consider $15 Minimum Wage”. New York: National Employment Law Project, May 28, 2014. http://www.raisetheminimumwage.com/media-center/entry/following-historic-seattle-agreement-chicago-becomes-next-city-to-consider-/

Robert Pollin, Mark Brenner, Jeannette Wicks-Lim & Stephanie Luce. A Measure of Fairness: The Economics of Living Wages and Minimum Wages in the United States. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008.

Nicholas Potter. “Earnings and Employment: The Effects of the Living Wage Ordinance in Santa Fe, New Mexico”. Albuquerque, NM: Bureau of Business and Economic Research, University of New Mexico, August 23, 2006. https://bber.unm.edu/pubs/SantaFeEarningsFinalReport.pdf

Nicholas Potter. “Measuring the Employment Impacts of the Living Wage Ordinance in Santa Fe, New Mexico”. Albuquerque, NM: Bureau of Business and Economic Research, University of New Mexico, June 30, 2006. https://bber.unm.edu/pubs/EmploymentLivingWageAnalysis.pdf

Michael Reich. “Increasing the Minimum Wage in San Jose: Benefits and Costs”. Berkeley, CA: Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, University of California, Berkeley, October 2012. http://www.irle.berkeley.edu/cwed/briefs/2012-01.pdf

Michael Reich, Ken Jacobs & Annette Bernhart. “Local Minimum Wage Laws: Impacts on Workers, Families and Businesses”. Seattle, WA: City of Seattle, Income Inequality Advisory Committee, March 2014. http://www.seattle.gov/council/issues/minimumwage/attachments/UC%20Berkeley%20IIAC%20Report%203-20-2014.pdf

John Schmitt. “The Minimum Wage Is Too Damn Low”. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, March 2012. http://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/min-wage1-2012-03.pdf

John Schmitt. “Why Does the Minimum Wage Have No Discernible Effect on Employment?” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, February 2013. http://www.cepr.net/index.php/publications/reports/why-does-the-minimum-wage-have-no-discernible-effect-on-employment

John Schmitt & David Rosnick. “The Wage and Employment Impact of Minimum-Wage Laws in Three Cities”. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, March 2011. http://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/min-wage-2011-03.pdf

The Economist. “Focus: Minimum wage”. London: The Economist, April 16, 2013. http://www.economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2013/04/focus-2

U.S. Census Bureau. “Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012”. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, 2013. https://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0756.pdf

Jeannette Wicks-Lim. “How High Could the Minimum Wage Go?”. Boston, MA: Dollars & Sense, July/August 2012. http://dollarsandsense.org/archives/2012/0712wicks-lim.html

Jeannette Wicks-Lim. “Measuring the Full Impact of Minimum and Living Wage Laws”. Boston, MA: Dollars & Sense, May/June 2006. http://dollarsandsense.org/archives/2006/0506wicks-lim.html

Note: This is an expanded, footnoted version of the article published on June 3, 2014 under the same headline by Inter Press Service.

English: Low-Wage Workers Butt Heads With 21st Century Capital. http://www.ipsnews.net/2014/06/low-wage-workers-butt-heads-with-21st-century-capital

Español: McDonald’s y la lucha por el salario mínimo en EEUU.

Seattle, Washington, United States

Note: This is an expanded, footnoted version of the article published on June 3, 2014 under the same headline by Inter Press Service.

English: Low-Wage Workers Butt Heads With 21st Century Capital. http://www.ipsnews.net/2014/06/low-wage-workers-butt-heads-with-21st-century-capital

Español: McDonald’s y la lucha por el salario mínimo en EEUU. http://www.ipsnoticias.net/2014/06/mcdonalds-y-la-lucha-por-el-salario-minimo-en-eeuu

“Supersize my salary now!” The refrain rose over a busy street outside a McDonald’s in downtown Seattle.

A young African-American mother carrying a little girl told the largely youthful crowd that she had walked off the job to join them because “we’re getting tired of being pushed around”. Her five-year-old took the microphone in both hands with a big grin and led a spirited chant: “We’re fired up, can’t take it no more!”

Green signs sported a hashtag, “Strike poverty 5-15-14 #FastFoodGlobal”, red t-shirts reasoned “Because the rent won’t wait – 15 now”, and a blue banner exhorted “$15 an hour plus tips. Don’t steal our wages.”

A few hundred ethnically diverse demonstrators filled a sunny afternoon with demands that fast-food chains pay a living wage. Dancers gyrated to Aretha Franklin’s ode to “R-E-S-P-E-C-T”. Seattle City Council member Kshama

Sawant said that workers in over 150 cities, including her hometown of Mumbai, India, had walked off their jobs that day.

Fast-food worker Sam Leloo captured the feeling of being trapped by low wages: “I believe in this movement because I’m trying to save enough to go to college and better myself. And I can’t go to college because I don’t make enough money. So it’s a Catch-22.”

According to the organizers, the Seattle event was one link in a chain of actions in over 30 countries by coalitions of grassroots worker centers, labor unions, community groups and faith organizations demanding better wages for fast-food workers.

This prosperous Pacific Northwest seaport, though, is the place in the United States closest to actually raising the minimum wage for all workers to something approaching a living wage. From the current Washington state minimum wage of $9.32 an hour, already the highest in the country, Seattle’s mayor, city council, and a majority of citizens according to some polls all support ratcheting up the wage over 60 percent to $15.00. The debate now centers on how long the ramp-up period should be for different-size businesses and non-profits, whether benefits and tips will be included in the wage, and other implementation details.

Seattle would seem a promising test case for these efforts. Home to aerospace giant Boeing and software powerhouses Microsoft and Amazon, the metropolitan area boasts relatively low unemployment and burgeoning technology jobs with good salaries. The electorate votes heavily Democratic and organized labor wields some influence.

Nationally, President Barack Obama has proposed an increase in the federal minimum wage. Democrats introduced legislation in both houses to raise it from the current $7.25 an hour to $10.10 an hour over two years, and index it to inflation thereafter.[1] Recent national polls show strong support for the raise, even among conservatives.[2] But the proposal was filibustered by Senate Republicans, throwing the initiative back to states and localities.

A national minimum wage was first established in 1938 by the Fair Labor Standards Act. Through 1968, it roughly tracked inflation, median wages and productivity. But sporadic increases since then have failed to keep up with prices, and the inflation-adjusted wage has never returned to its 1968 high. Meanwhile, it has fallen far behind productivity growth: had it kept pace, according to economist John Schmitt of the Center for Economic and Policy

Research, by 2012 it would be nearly three times as high, $21.72 instead of $7.25.[3]

To bypass the federal stalemate, since the 1990s state and local efforts to raise minimum wages have proliferated. In the decentralized U.S. legal system, states and localities can set their own minimum wages, with the highest benchmark applying. Twenty-six of the 50 states have raised or are raising their base wages above the federal level, with increases scheduled in eight states and the District of Columbia.[4] More than 120 cities have also raised their benchmarks,[5] and besides Seattle, efforts are underway in San Francisco, Oakland, Los Angeles, San Diego, Chicago, New York and Portland, Maine.[6]

This resurgent movement to raise the floor of the labor market is surfing the zeitgeist of renewed international debate on economic inequality. “Capital in the Twenty-First Century”, the chef d’oeuvre of French economist Thomas Piketty, has levitated to number one on the New York Times non-fiction bestseller list.[7] Piketty documents “forces of divergence” in modern capitalism driving current levels of wealth concentration unequalled since the 1920s. To remedy some of the “potentially terrifying” consequences of these “long-term dynamics of the wealth distribution”, he proposes a global tax on wealth.[8]

Piketty is no prophet crying in the wilderness. Institutions as influential as the International Monetary Fund and the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank have joined the chorus.

IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde has flagged “rising income inequality” as “a growing concern for policy makers around the world.” Equity along with growth, she has pointed out, are “necessary for stability”, which in turn is “essential for reducing poverty”. The IMF, Lagarde has said, should foster “fiscal policies to reduce poverty” and advance “inclusive” growth.[9] Lagarde previously served as Finance and Economy Minister in the center-right French government of Nicolas Sarkozy and chaired the G-20 for France.[10]

Fed chair Janet Yellen has called “a huge rise in income inequality” going back to the 80s “one of the most disturbing trends facing the nation”.[11]

Both the IMF and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development have recently recognized that moderate minimum wage raises may be beneficial.[12]

As a non-fiscal means of raising the ground floor of the income pyramid, minimum wage hikes have proved attractive even to some conservatives, in part because they do not require direct outlays by cash-strapped governments.

The Economist magazine, a British champion of market hegemony, has swung from opposition to grudging acceptance that measured minimum wage increases can do more good than harm.[13] Another business-friendly voice, the U.S. news service Bloomberg, has editorialized in favor of raising the national minimum.[14]

Conservative British Finance Minister George Osborne recently advocated an increase in the U.K. base wage.[15] And center-right Chancellor Angela Merkel approved Germany’s first minimum wage legislation in April. Pending parliamentary ratification, the benchmark will be set at 8.50 euros (US$ 11.75) in 2015.[16]

Compared to other wealthy countries, working for the Yankee dollar pays poorly at the low end. The U.S. minimum wage of $7.25 was a miserly 38.3 percent of its 2012 median wage. Britain’s ratio was 46.7 percent, slightly above the European Union average, while France led with a minimum 60.1 percent of its median. Of major industrialized nations, only Japan, at 38.4 percent, had a percentage of median nearly as low as the U.S. one.

As the minimum wage in much of the United States falls ever farther behind the economy, labor-market and demographic undertows have constrained increasingly older and more-educated workers to take low-wage jobs.

In 1979, 26 percent of low-wage workers (making $10 an hour or less in 2011 dollars) were under 20 years old, 39.5 percent had less than a high-school diploma, and 25.2 percent had some university or a university degree. By 2011, only 12 percent were under 20 and 19.8 percent had completed less than high school, a drop of roughly one-half for each measure. The proportion with at least some college had grown to 43.2 percent, an increase of more than two-thirds. Fifty-five percent of minimum wage workers were women, and 43 percent were people of color, both above their respective proportions in the U.S. workforce.[17]

The stereotype of low-wage workers as mainly high-school kids earning extra pocket money, never very accurate, has been made obsolete by decades of economic tsunamis washing away better-paying manufacturing jobs.

Nevertheless, some politicians and business groups confront each proposed minimum wage increase with stern warnings that it will destroy jobs. Historically, though, the predicted damage has yet to materialize.