SUSRIS Editor’s Note: Over the last two years the twin crises in Egypt and Syria have placed a heavy diplomatic and security burden on leaders and policymakers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United States. Washington and Riyadh have worked closely [...]]]>

SUSRIS Editor’s Note: Over the last two years the twin crises in Egypt and Syria have placed a heavy diplomatic and security burden on leaders and policymakers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United States. Washington and Riyadh have worked closely to formulate responses to the unfolding catastrophes in these countries as well as complex national security troubles unfolding across the region. As with any bilateral relationship American and Saudi interests do not always coincide as has been displayed in the reaction to the coup and crackdown in Egypt. The prospects for a military response to the use of chemical weapons in the Syrian civil war only adds to the difficulties of forging a common approach to the new regional realities.

To provide context to these urgent issues SUSRIS called onAmbassador Chas W. Freeman, Jr., to share insight and perspective on the diplomatic consequences for Washington and Riyadh. Freeman’s distinguished career included service as US Ambassador to Saudi Arabia during Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm and as Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs. He was the President of the Middle East Policy Council and vice chair of the Atlantic Council of the United States. Freeman is Chairman of the Board of Projects International, Inc. We spoke with Ambassador Freeman by phone from his home in Rhode Island on August 27, 2013.

[SUSRIS] Thank you for taking time to talk about the crises in Syria and Egypt and the fallout for American ties with its allies in the region, especially the US-Saudi relationship.

All eyes have shifted from the coup and crackdown in Egypt and the American reaction to it, to the increasing likelihood that the United States will take the lead in a military response to last week’s use of chemical weapons in Syria. In what ways are there agreements and differences in the policies of Washington and Riyadh over Egypt and Syria?

[Amb. Chas W. Freeman, Jr.] There is actually a fair amount of convergence in short-term Saudi and American objectives with respect to Syria, but probably some divergence in long-term views, which we can get back to. At the moment there are serious divisions of opinion between the United States and Saudi Arabia that mainly find expression in our policies toward Egypt.

It’s no secret that the Royal Family in Saudi Arabia was shocked when the United States first vacillated and then withdrew its support from President Mubarak. This seemed to them to show that the United States was an unreliable protector. Obviously protection has been one of the services that the Saudi Royal Family has traditionally looked to the United States to provide. The Mubarak situation catalyzed Saudi reactions borne of over a decade of growing exasperation with U.S. policy. While the Saudis don’t want to give up the relationship with the U.S. – for some purposes the U.S. remains a valued partner, they have concluded that in many respects they’re on their own. They see they now have to act unilaterally in defense of their own interests, even when this puts them at odds with the United States.

Now we see a strong Saudi intervention in Egypt on behalf of autocracy. The effort to make the region safe for autocracy directly counters the American ideology of democratization. In the Saudi judgment, recent experience shows that democratization leads inevitably to the triumph of political Islam. Islamist democratism is a challenge to the legitimacy of the Saudi monarchy, which is based on the notion that in Islamic societies there is a religiously enlightened leader, an emir, who leads the Muslim community, the Ummah. While the emir’s leadership has to be responsive to opinion and political consensus, it is ultimately autocratic.

This idea contrasts with the western notion that sovereignty is or should be exercised from the bottom up through elections. So we have a fundamental disagreement on Egypt. We probably have the same disagreement, although less obviously, in the case of Bahrain. It was there that, from the Saudi perspective, the first effects of the Mubarak debacle in the Arabian Peninsula were felt.

The turmoil in Egypt has led to the emergence of some degree of entente between the Saudis and the Russians on the issue of autocracy and opposition to militant Islamist populism. The Russians see an opportunity in Egypt as the Egyptians reconsider their dependence on the United States – perhaps in part reversing the Egyptian switch to American protection that Sadat pulled off. The Russians may try to work with the Saudis, the Emiratis, and others wealthy autocracies in the Gulf to reestablish a military supply and strategic relationship with Egypt that would once again give them significant influence in the Middle East beyond Syria. This has clearly been discussed, at least in a preliminary way, between Prince Bandar bin Sultan and Vladimir Putin. So I think Saudi-American disagreements over Egypt are not trivial.

There are other sore points dating back to the invasion of Iraq. Some Saudis favored the invasion, but most at the top clearly did not. It badly backfired in terms of establishing a pro-Iranian, Shiite-dominated regime in Baghdad. The U.S. attempted for some time to broker rapprochement between Riyadh and Baghdad but I think it has now concluded this is impossible and given up.

There is also a difference in opinion between us about how much of a supporter Malaki is for the Assad regime in Damascus. And I don’t think the Saudis have lost their sympathy for the Sunni minority in Iraq or their desire to see it reestablish itself in a position of at least equality, maybe even more, in Iraqi politics.

In Syria, as I said, we have a short-term convergence of interest. We both wish to remove Syria from the asset side of Iran’s geo-strategic balance sheet. We both oppose Hezbollah. We both would both like to see Assad out. In the end, however, we may not agree about the future of Syria. The Saudis have a strong interest in the territorial integrity of Syria. The United States may not share that interest. Certainly Israel, our principle partner on these matters, does not. The Saudis may see a future Sunni-dominated Syria as a platform from which to remove Iraq from the Iranian orbit. I don’t think Americans have thought much about the implications of that.

There’s a lot of confusion and cognitive dissonance. Many things are in motion between the United States and Saudi Arabia with respect to the overall configuration of the region. The Arab uprisings were about Arabs re-seizing control of their own destiny. This began in Tunisia and Egypt and spread. It has now affected Saudi Arabia in the sense that the Saudis are also attempting to seize control of their own destiny and regional role, in both of which the US will necessarily play a diminished part.

[SUSRIS] Saudi and UAE officials were said to have warned the US Secretary of State of consequences for US ties, especially in the area of security concerns, over the question of American support for Egypt according to a Wall Street Journal article. King Abdullah warned that Saudi Arabia stood against those who tried to interfere in Egypt’s domestic affairs. You were quoted by Jim Lobe as saying, “The Al-Saud partnership with the United States has not only lost most of its charm and utility; it has from Riyadh’s perspective become in almost all respects counterproductive.” Yet, the Obama Administration engaged in weeks of verbal gymnastics to keep from calling the coup a coup and has so far only reacted with token measures against the bloody crackdown against the Muslim Brotherhood. Is there that much daylight between Riyadh and Washington on the Egypt issue to warrant such a high-pitched reaction?

[Freeman] Riyadh is very realistic. When Mubarak was removed from office there was the shock, which I described, and an absence – from the Saudi perspective – of a helpful and supportive American reaction. The Saudis embraced the new reality and tried to make the best of it, but then they saw several things happen which they didn’t like. First, in foreign policy Morsi reached out to Iran, which Saudi Arabia sees as its principle regional rival. Morsi’s government did not have the negative view of Hamas that Riyadh does. As the Morsi government proved to be incompetent, demonstrating that the Muslim Brotherhood and Islamists in general lack a coherent and effective economic philosophy or policy, Saudi Arabia saw Egypt drifting into anarchy and alignments that were contrary to its interests. Saudi Arabia very much welcomed and may even have encouraged the overthrow of Morsi. By any definition, notwithstanding the tortured legal fictions that prevail in Washington, it was a coup. The Saudis are pleased that the U.S. has not said that.

The Saudis do not want the United States to break with the al-Sisi government in Cairo. On the contrary, they would like the U.S. to support that government, as they do. Our support has been equivocal. The military aid relationship has not been solidly reaffirmed. It has been under review. Things have been moving on a case-by-case basis. American statements have — true to our values — continued to attempt to balance ideological commitments to democratization with our in interest in preserving the Camp David structure and the Egyptian cooperation with Israel, which are central to our position in the Middle East.

So we haven’t had an open break, but we’ve been very firmly warned by the Saudis. If we do suspend assistance, they will step in and repair whatever damage is done to the Egyptian Armed Forces. They have in effect deprived us of a considerable amount of leverage over the Egyptian Army.

This is the first time that I have seen so open, in fact much of any, open or concealed Saudi divergence from U.S. policy objectives. In the past the Saudi tendency has been to register objections but to refrain from undercutting U.S. policies they don’t like. Now they’re acting. And this goes back to the point I was making that they, like others, in the region have decided to take matters into their own hands.

Egypt has a history of switching sides, making dramatic readjustments in its strategic orientation. Ultimately that is what’s at stake here. The United States should exercise caution with Egypt. We could provoke a return of Egyptian strategic deference to Moscow. Of course, we’re not in the Cold War, and Russia is not our enemy. But it is a diplomatic rival, and were Egypt to return to military supply and training relationships with Russia under circumstances where the Egyptian army was running Egypt, this would have ramifications that go well beyond the question of our priority use of the Suez Canal or reliable transit rights over Egyptian airspace. I think that’s one element of this, but far from the only one.

[SUSRIS] How do the warnings from Saudi Arabia and the U.A.E. officials that security cooperation elsewhere in the region might be affected fit in here?

[Freeman] Well this is, of course, another issue. Let’s consider for a moment on a speculative basis, because that’s all it is at this point, what factors might go into a Saudi-Russian entente, maybe a Saudi-Russian entente including others in the GCC. First of all we need to remember that the strategic utility of the United States to Saudi Arabia in relation to Israel has been reduced. Our long default on peacemaking means that we are no longer on the right side of the effort to inhibit the Israel-Palestine issue’s radicalization of Arab politics. Moreover, it is obvious that we cannot control or even constrain unilateral actions by Israel against neighboring countries including, Saudi Arabia. So we don’t perform the protective roles we once did with respect to the region’s greatest military power.

Then, too, our actions in Iraq inadvertently strengthened Iran. We gave Iran a friendly and, in some respects, allied Iraq, instead of an Arab enemy that balances it. Iraq shares Iran’s interests, for example, with respect to Bahrain, which is a core Saudi security concern. We’ve also failed, from the Saudi perspective, to come up with an effective way of reversing, or even checking the growth in Iranian prestige and influence in the region. From Riyadh’s perspective, Iran is not just a nuclear issue although that’s part of it. In the case of Iran, many Saudis accuse us of errors of omission in addition to errors of commission in Iraq and Lebanon. So they don’t see us as they once did.

This brings us to Saudi and Russian interests. There are now many coincidences between them. First, both Riyadh and Moscow favor autocratic regimes. In Egypt the Russians may see an opportunity to regain influence with Saudi help. The Saudis may see an opportunity to offset objectionable American policies by either paying for or helping to arrange Russian arms transfers to replace those that we suspend or cancel. With respect to Bahrain, of course the Russians have no objection to Saudi or GCC policies. With respect to Iran, relations between Moscow and Tehran are good on a day-to-day basis but the two remain strategic rivals. Russia is in the region. It can’t come and go as we do. Russia has the potential capacity to balance Iran from the north, not in the Gulf, without the socio-political complications that our presence there entails.

Russia is also a historic rival of Turkey. Relations between Moscow and Ankara have never been better but their rivalry continues just below the surface. The Saudis are against the Turkish model of Islamist democratism and do not have an interest in advancing Turkish foreign policy objectives, especially in Egypt.

Finally, strangely enough, about twenty percent of Israelis are Russian so the Russians have some unexpended influence in Israel to bring to bear should it choose to do so. So the attractions of trying to work out a Saudi-Russian entente are there. By entente, I mean a framework for limited cooperation on a limited set of issues, perhaps for a limited period time.

There also are a lot of difficulties in the way of Saudi-Russian cooperation. Let me take one of them.

If you look at Syria the primary Saudi objective is to remove it from the Iranian orbit and undercut Hezbollah. Secondarily, they want to remove Assad from office. From the Saudi perspective, he has been dishonest, deceitful, and dishonorable. Riyadh would like to see him go and his regime with him. However, the primary objective is to eliminate Iranian influence and to undercut Hezbollah, which has emerged as the dominant political force in Lebanon, where it contests Saudi influence. There may also be a Saudi objective of using a reoriented Syria, as I suggested, to try to retake some or all of Iraq for Sunni Islam, reducing Iranian influence there.

Assad is a secondary issue. What the Russians have wanted to do in Syria in addition to protecting their commercial interests, their naval base, and their relationships with the Syrian elite, is to draw a contrast between their own stalwart support for the beleaguered Assad and the American abandonment of Mubarak. They want to show that they are a reliable protector and partner.

Syria is now de facto partitioned in many respects, and the Assad regime does not even control many of the elements that support it. In some cases they are taking on the characteristics of warlords or gang leaders, even self-financing with smuggling and extortion and protection rackets and other activities. The only way one could imagine Assad surviving after a graceful interval and being allowed to withdraw with dignity from a Syria he can no longer control is if the Saudis and the Russians cooperated to accomplish that. Depending on what was agreed, that could perhaps achieve the Saudi objective of cutting the Damascus’ ties with Tehran. It could also accomplish the Russian objective of not having Assad overthrown, but withdrawing with some dignity. This is a real long shot but not impossible to imagine.

So you could see a situation in which both sides gained from the strategic reorientation of Syria and from the orderly removal of Mr. Assad. I suspect that there will be some talk about this, although it appears the initial Saudi approach to the Russians was another effort to persuade them to do what Saudi Arabia would prefer, which is simply to get rid of Mr. Assad at the outset. That can’t have gotten very far but it is not necessarily the end of the story.

[SUSRIS] It was done in a surprisingly public way. Prince Bandar could have made his meeting with President Putin without posing for the cameras.

[Freeman] There are many games going on here, and one of them is a reminder to the United States that there’s more at stake than we tend to imagine.

[Freeman] There are many games going on here, and one of them is a reminder to the United States that there’s more at stake than we tend to imagine.

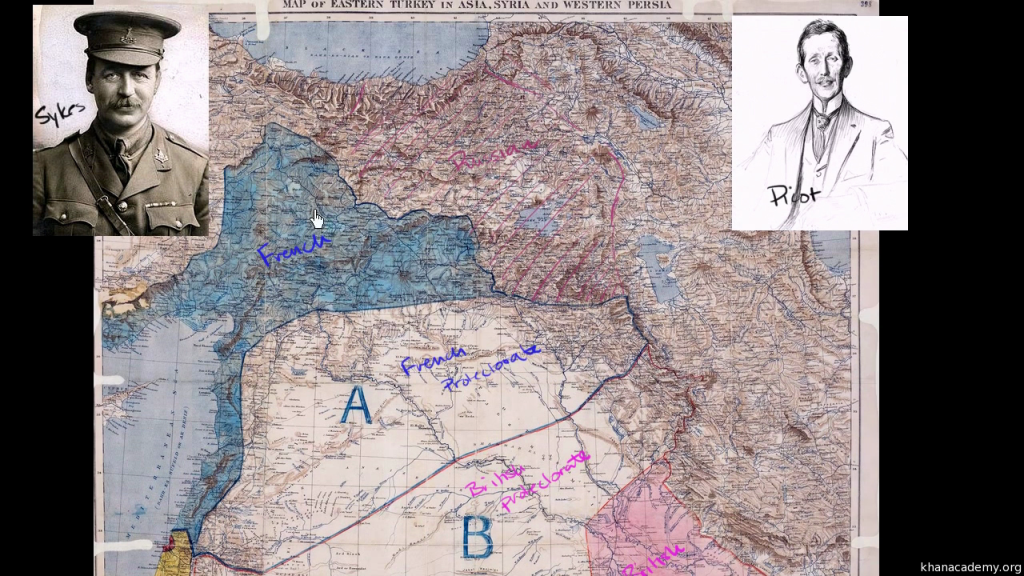

The world that has existed in the Middle East is changing. Mr. Sykes’ and Mr. Picot’s work is coming undone. Strategic orientations of the past cannot be taken for granted. Saudi Arabia itself has got its own interests and requirements for policy and cannot be taken for granted by the United States, as we’ve often tended to do.

Additionally, by going to Moscow, the Saudis undoubtedly hoped to unnerve Bashar Al-Assad and Tehran and put pressure on both.

Finally there’s another factor and that is Russia and Saudi Arabia – the two largest oil producers and exporters in the world – are concerned about how to cope with the resurgence of American production of oil and gas from shale and other unconventional sources. Apparently one of the things that was discussed was some sort of arrangement for coordination to sustain oil prices at what the two sides consider to be a reasonable level. This is another previously improbable but new and potentially significant subject for these two governments to explore.

[SUSRIS] Now that Syria has displaced Egypt in the headlines and Washington is ready to act against Assad is there likely to be a change in language about the disagreements or policy moving forward?

[Freeman] Both governments have an interest in sustaining an appearance of harmony and cooperation between them. What does it benefit either to appear to separate from the other, unless and until some major strategic deal that has advantages for one side or the other is struck? I wouldn’t expect either side to be very honest or forthcoming about what it thinks about the actions and activities of the other. Of course if the United States attacks Syria I expect the Saudis will be delighted since they have been urging a more active American support of the opposition and opposition to Assad for eighteen months anyway.

[SUSRIS] Is there a risk that a limited punitive strike, along the lines of what is being discussed, will do little to change the situation, the catastrophe that it is, and with Assad still in power?

[Freeman] Here we have to quite cynically recognize some realities. The first is that if the primary objective of both Saudi Arabia and the United States, and some other countries in the region, is to remove Syria from Iran’s embrace, then anarchy and mayhem are the next best thing to regime change.

The case has been made, most recently in the New York Times by Edward Luttwak, that the United States would lose if either side won. Therefore, the argument goes, the best thing is for the fighting to go on. Now that of course is a reminder of some of the more absurd elements of the “red line” about the use of chemical weapons. In a week where the Egyptian army killed a thousand people, the Syrian government was accused – rightly or wrongly, we don’t know – of having killed three or four hundred people, as if it was the use of the weapon involved, not the deaths that really mattered. One hundred thousand people or more have died in Syria with the United States and others doing very little of an overt nature. The international community remains divided on this subject. Some might argue that it displays an odd set of humanitarian priorities.

So, this is one set of issues. Another is that this effort to use precision strikes to alter the situation on the ground in Syria is unlikely to be effective. Look at what has happened in Syria. A very fractured opposition now confronts an increasingly fractured regime, with militias operating under local warlords or gang leaders. They are carrying on a great deal of their struggle not so much in support of the regime as in defense of the ethnic communities that depend on the regime — the Christians, the Alawites, secular groups who don’t like the Islamists who dominate the opposition.

It’s entirely possible that a strike on chemical weapons facilities would result in the degradation and devolution of control over the chemical weapons to these warlords and feudal barons, meaning that it would further dilute the government’s control of chemical weapons, and greatly increase the probability of their use by people without the knowledge or support of whatever regime remains in place in Damascus.

This is an extremely dangerous situation. Far more dangerous still is the question of what follows the Assad regime. And here is where I think the United States and Saudi Arabia may turn out to have some serious differences. The Saudi tolerance of Salafi Muslims is a great deal higher than that of the United States. After all, Saudi Arabia is officially Salafi. And while we have a common enemy in Al-Qaeda, the Jihadi elements who attack us also attack Saudi Arabia, or perhaps it’s the other way around – those who attack Saudi Arabia also attack us. To the extent there’s daylight between the United States and Saudi Arabia, their incentive to focus on Saudi Arabia rather than the United States goes down. That is to say that the probability of a Jihadi focus on the United States goes up. That would be an ironic result indeed of what I take to be an effort by the Saudis in Syria and Lebanon to reduce the danger of terrorism against their own society.

[SUSRIS] Let’s return to the U.S.-Saudi relationship. The partnership is much more complex than any one element of the security component. Let’s look at US-Saudi relations in their totality, and the history of recurring ups and downs, in the past you referred to it as being a marriage. How would you describe the playing field going forward, looking at the scope of business ties and all of the things that are held as being values in the relationship?

[Freeman] It’s a much more fluid and dynamic relationship now than it was, with many things in motion going in different directions. It’s more like a polo field than it is like the stable relationship characteristic of marriage. There are a lot of gopher holes in the field that can break the legs of the horses who are playing the game.

If you look at the various interests that have brought us together, there is the tradeoff of energy for security. As I’ve pointed out the Saudis no longer have much confidence in our ability to deliver security for them. They also see us, I suspect, as an increasingly problematic factor in global energy markets given our rapid ramp up in oil production and our gas exports. The question of cooperation on Islamic issues has been moot for quite a while. We’re very much at odds on that, although I continue to believe that under King Abdullah there have been major opportunities for us to cooperate with the Saudis in pulling the fangs of the Jihadi movement, which we have not seized. It’s a tragedy that we have not done so.

We have a continuing interest in freedom of transit through the air and sea space in the Arabian Peninsula and around it as the discussion of Egypt in the Wall Street Journal that you cited brings out. That continues on a case-by-case basis with no overall framework that guarantees it. It’s clearly related to Egyptian decisions on these matters and perhaps cannot be taken quite so much for granted as in the past.

The Saudis continue to use their connections to the United States, I think very wisely and skillfully, to expose a younger generation of lower-middle class Saudis to come to the modern culture of the United States. There’s a huge number of students here under the King’s scholarship program.

The U.S. continues to be a very significant presence in Saudi commercial markets but in terms of market share we have been a diminishing presence. In every respect we are not the destination for Saudi oil exports we once were. We’re not the source of imports we once were. Others have a greater role.

With respect to cooperation in foreign policy, the Saudis are clearly looking around for ways to dilute what they regard as over-dependence on the United States. This is not a particularly promising arena for cooperation in the short term.

Finally, cooperation on counterterrorism brings us squarely to the irony that it is in many respects Saudi closeness to the United States, and therefore to American policies on issues like the Israel-Palestine issue, that makes Saudi Arabia a target for Islamist terrorists. Therefore, the closer our cooperation, public cooperation, arguably the greater the cost it will be to Saudi Arabia in this arena. Nevertheless, we do have the same enemy, and I would expect our cooperation to continue, though perhaps with less publicity.

To sum all this up I would say that neither side can do without the other, or wants to do without the other, but the Saudis are much more prepared than in the past to reduce their reliance on the United States and to seek new partners and new directions.

[SUSRIS] Can you remember any point in American diplomatic history where there has been such a convoluted collection of circumstances as we see now in the Middle East?

[Freeman] Last fall I gave two speeches on the changing world order, one called“Paramountcy Lost” [Challenges for American Diplomacy in a Competitive World Order] the other called “Nobody’s Century” [The American Prospect in Post Imperial Times]. The key point is that it’s not just the Middle East but everywhere there is a decentralization of political and economic power. Militarily we Americans are still unmatched but in the other spheres we now have effective rivals on the regional and sometimes even on the global level.

The complexity of foreign affairs now requires a level of agility from Americans that we have not historically displayed. We’re good at wars of attrition and the diplomatic equivalent of trench warfare, not blitzkrieg.

What we are confronting now is the possibility, still just a possibility, still reversible, that the entire landscape in the Middle East that we have been accustomed to, could be rearranged by some geostrategic earthquake.

I think there is a broader context here. The Saudis are looking out for their interests first, in a way that frankly they did not in the past. The Saudi concept has been that friends defer to the interest of friends. Since the United States does not defer to anyone else’s interests these days, not surprisingly, Saudi expectations and behavior are different now. We have interests that differ from theirs. They are not treating us with the deference they once did. They are pursuing their own interests and policies. I think we need to reexamine our own interests. I think our interests dictate a strong relationship with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia but some of the policies we have followed in the Middle East have clearly been counterproductive and others have been ineffectual. We need to rethink things.

]]>by Chas Freeman

An acquaintance who, like me, used to work on foreign affairs in the U.S. government, told me the other day that he thought that, in going after Bashar al-Assad, President Barak Obama had decided on an approach more akin to Bush 41 (carefully building a consensus) than Bush 43 [...]]]>

by Chas Freeman

An acquaintance who, like me, used to work on foreign affairs in the U.S. government, told me the other day that he thought that, in going after Bashar al-Assad, President Barak Obama had decided on an approach more akin to Bush 41 (carefully building a consensus) than Bush 43 (you are either with us or against us). He added that, to make a success of bombing Syria as Bush 41 made of bombing Iraq in the first Gulf War, the president didn’t just need the support of the Congress and the public but also of NATO, the Arab League, and a coalition of the willing. But the obstacles Obama faces are much greater than those George H. W. Bush did and I don’t think the analogy to the first Gulf War really holds.

The circumstances today are totally different than in 1990, when strong impulses to rally behind the United States borne of the Cold War continued to animate allied decisions. There is no longer a common external threat to draw other countries into formation behind us. Two decades of perceived American indifference to allied and friendly views on a wide range of issues have taken their toll, especially in the Middle East and Europe. The Syrian issue, although greatly complicated by foreign players within the region and beyond it, has no global context of Manichean struggle to channel reactions to it.

In 1990-1991, as the USSR collapsed, the Russians ceased to be a significant factor in the Middle East, erasing the bipolar order of the past and freeing Saddam wrongly to assume that he could act on his own and with impunity against Kuwait. In 2013, the region is driven by regional rather than global dynamics but, thanks to events in Egypt and Saudi disillusionment with the U.S. policies of the past thirteen years, Russia is on the make and poised for a comeback as a strategic player in the Middle East.

In 1990, the world’s Muslims were solidly anti-communist and mostly well-disposed to the United States. Anti-communism is now an irrelevancy. The fallout from 9/11, the failed American pacification campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, and U.S. identification with Israel’s attacks on Lebanon and Gaza have replaced Muslim goodwill with animosity. The appeal of American values has been tarnished by numerous abuses, and the worldwide credibility of U.S. intelligence is low. The British defection from the enterprise leaves our pretensions to speak and act for the “international community” in tatters. (The poodle has left the American lap and walked off the job. The French are halfheartedly applying for the position. They aren’t house-trained and will want too much to get it.)

Major actors in the international community, such as it is, value the institutions that embody it, the U.N., the U.N. Charter, and international law, to none of which the U.S. has deferred, except highly selectively, since our Kosovo intervention with NATO in October 1998. Fifteen years of selective adherence to treaties and laws greatly detract from the credibility of our claim now to be acting to enforce the Geneva Convention of 1929 in Syria, especially when the “international community” as well as the Arab League and our own allies have declined to authorize us to do so. Abroad, we are not seen as righteous vigilantes on behalf of humanitarian principles but as proponents of the theses that military might confers right, that military actions trump diplomacy (which is mostly just for show), and that political solutions are for wimps. There will be no international rally behind an essentially unilateral U.S. attack on Syria. On the contrary, if we carry out such an attack, it will further diminish our international standing and leadership. Illegal actions to enforce legality are the very definition of cynicism.

When Saddam invaded Kuwait in 1990, it was a clear and abrupt challenge to the rule of law in the post-Cold War era, not to mention an obvious threat by a single, very selfish state to monopolize the world’s major sources of energy. From the outset, the U.S. and Saudi Arabia sought and received U.N. authorization to “form a posse” to deal with these challenges. The atrocities in Syria are the product of a civil war, not of a violation of any other country’s sovereignty. The situation in Syria is also an unfolding humanitarian catastrophe that has been allowed to fester for over two years, with respect to which the U.N. has been marginalized and is now ignored by us and some other players. Whatever happens, it is highly unlikely that we will accede to the desire of other great powers that we defer to the U.N. and hence to their interest in international norms of behavior. For this reason, President Obama is likely to take a drubbing from allies, friends, and adversaries alike at the upcoming G-20 meeting in St. Petersburg, where he must make the case for what he has unilaterally decided but Congress has yet to approve.

To my mind, the most interesting and significant aspect of what has just happened — the issuance of an order to attack, followed by its sudden suspension until Congress can review it — is the domestic rediscovery of the fact that wars cannot be successfully mounted or sustained without a measure of domestic political backing. (In tactical terms, this is an attempt to share the political blame and pin the charge of vacillation and weakness on the Republican House.) There is a chance that, in the course of debating the order to attack Syria, someone will actually read our Constitution (Article I, Section 8, Clause 11) on how wars are to be legally authorized. I note that, in his statement Saturday, the president claimed inherent authority to make war. I hope that this concept, like the divine right of kings in its pedigree, is appropriately challenged in the debate. Unfortunately, the divine right of legislatures, an equal problem in the breakdown of the separation of powers and hence the operation of our system of government, will not be challenged.

Getting our country, our government, and the president’s authority in foreign affairs into the multiple conundrums in which they now find themselves was the work of many administrations and Congresses, not just poor Mr. Obama (as the venerable Israeli peace activist, Uri Avnery aptly termed him in a recent column). I don’t think anyone could envy the position our president is now in domestically or internationally. He was dealt a bad hand. He has not played the game in such a way to pick up better cards since. Now his bluff has been called.

– Chas Freeman served as U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia during the war to liberate Kuwait and as Assistant Secretary of Defense from 1993-1994. Since 1995, he has chaired Projects International, Inc., a Washington-based firm that creates businesses across borders for its American and foreign clients. He was the editor of the Encyclopedia Britannica entry on “diplomacy” and is the author of five books, including “America’s Misadventures in the Middle East” and “Interesting Times: China, America, and the Shifting Balance of Prestige.”

via IPS News

As the administration of President Barack Obama continues wrestling with how to react to the military coup in Egypt and its bloody aftermath, officials and independent analysts are increasingly worried about the crisis’s effect on U.S. ties with Saudi Arabia.

The oil-rich kingdom’s strong support [...]]]>

via IPS News

As the administration of President Barack Obama continues wrestling with how to react to the military coup in Egypt and its bloody aftermath, officials and independent analysts are increasingly worried about the crisis’s effect on U.S. ties with Saudi Arabia.

The oil-rich kingdom’s strong support for the coup is seen here as having encouraged Cairo’s defence minister Gen. Abdul Fattah al-Sisi to crack down on the Muslim Brotherhood and resist western pressure to take a conciliatory approach that would be less likely to radicalise the Brotherhood’s followers and push them into taking up arms.

Along with the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait, Saudi Arabia did not just pledge immediately after the Jul. 3 coup that ousted President Mohamed Morsi to provide a combined 12 billion dollars in financial assistance, but it has also promised to make up for any western aid – including the 1.5 billion dollars with which Washington supplies Cairo annually in mostly military assistance – that may be withheld as a result of the coup and the ongoing crackdown in which about 1,000 protestors are believed to have been killed to date.

Perhaps even more worrisome to some experts here has been the exceptionally tough language directed against Washington’s own condemnation of the coup by top Saudi officials, including King Abdullah, who declared Friday that “[t]he kingdom stands …against all those who try to interfere with its domestic affairs” and charged that criticism of the army crackdown amounted to helping the “terrorists”.

Bruce Riedel, a former top CIA Middle East analyst who has advised the Obama administration, called the comments “unprecedented” even if the king did not identify the United States by name.

Chas Freeman, a highly decorated retired foreign service officer who served as U.S. ambassador to Riyadh during the Gulf War, agreed with that assessment.

“I cannot recall any statement as bluntly critical as that,” he told IPS, adding that it marked the culmination of two decades of growing Saudi exasperation with U.S. policy – from Washington’s failure to restrain Israeli military adventures and the occupation of Palestinian territory to its empowering the Shia majority in Iraq after its 2003 invasion and its abandonment of former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak and its backing of democratic movements during the “Arab awakening”.

“For most of the past seven decades, the Saudis have looked to Americans as their patrons to handle the strategic challenges of their region,” Freeman said. “But now the Al-Saud partnership with the United States has not only lost most of its charm and utility; it has from Riyadh’s perspective become in almost all respects counterproductive.”

The result, according to Freeman, has been a “lurch into active unilateral defence of its regional interests”, a move that could portend major geo-strategic shifts in the region. “Saudi Arabia does not consider the U.S. a reliable protector, thinks it’s on its own, and is acting accordingly.”

A number of analysts, including Freeman, have pointed to a Jul. 31 meeting in Moscow between Russian President Vladimir Putin and the head of the Riyadh’s national security council and intelligence service, Prince Bandar bin Sultan, as one potentially significant “straw in the wind” regarding the Saudi’s changing calculations.

According to a Reuters report, Bandar, who served as Riyadh’s ambassador to Washington for more than two decades, offered to buy up to 15 billion dollars in Russian arms and coordinate energy policy – specifically to prevent Qatar from exporting its natural gas to Europe at Moscow’s expense – in exchange for dropping or substantially reducing Moscow’s support for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

While Putin, under whom Moscow’s relations with Washington appear to have a hit a post-Cold War low recently, was non-committal, Bandar left Moscow encouraged by the possibilities for greater strategic co-operation, according to press reports that drew worried comments from some here.

“[T]he United States is apparently standing on the sidelines – despite being Riyadh’s close diplomatic partner for decades, principally in the hitherto successful policy of blocking Russia’s influence in the Middle East,” wrote Simon Henderson, an analyst at the pro-Israel Washington Institute for Near East Policy (WINEP).

“It would be optimistic to believe that the Moscow meeting will significantly reduce Russian support for the Assad regime,” he noted. “But meanwhile Putin will have pried open a gap between Riyadh and Washington.”

As suggested by Abdullah’s remarks, that gap has only widened in the wake of the Egyptian military’s bloody crackdown on the Brotherhood this month and steps by Washington to date, including the delay in the scheduled shipment of F-16 fighter jets and the cancellation of joint U.S.-Egyptian military exercises next month, to show disapproval.

U.S. officials have told reporters that Washington is also likely to suspend a shipment of Apache attack helicopters to Cairo unless the regime quickly reverses course.

Meanwhile Moscow, even as it joined the West in appealing for restraint and non-violent solutions to the Egyptian crisis, has also refrained from criticising the military, while the chairman of Foreign Affairs Committee of the Duma’s upper house blamed the United States and the European Union for supporting the Muslim Brotherhood.

“It is clear that Russia and Saudi Arabia prefer stability in Egypt, and both are betting on the Egyptian military prevailing in the current standoff, and are already acting on that assumption,” according to an op-ed that laid out the two countries’ common interests throughout the Middle East and was published Sunday by Alarabiya.net, the news channel majority-owned by the Saudi Middle East Broadcasting Centre (MBC).

Some observers argue that Russia and Saudi Arabia have a shared interest in containing Iran; reducing Turkish influence; co-operating on energy issues; and bolstering autocratic regimes, including Egypt’s, at the expense of popular Islamist parties, notably the Brotherhood and its affiliates, across the region.

“There’s a certain logic to all that, but it’s too early to say whether such an understanding can be reached,” said Freeman, who noted that Bandar “wrote the book on outreach to former ideological and geo-strategic enemies”, including China, and that his visit to Moscow “looks like classic Saudi breakout diplomacy”.

But reaching a deal on Syria would be particularly challenging. While Riyadh assigns higher priority to reducing Iran’s regional influence than to removing Assad, some analysts believe there are ways an agreement that would retain him as president could be struck, as Moscow insists, while reducing his power over the opposition-controlled part of the country and weakening his ties to Tehran and Hezbollah.

But Mark N. Katz, an expert on Russian Middle East policy at George Mason University, is sceptical about the prospects for a Russian-Saudi entente, noting that Bandar has pursued such a relationship in the past without success.

“I’m not saying it can’t work, but this has been his hobby horse,” he told IPS. “Whatever happens in Saudi-American relations, however, the Saudis don’t trust the Russians and don’t want them meddling in the region. Everything about the Russians ticks them off.”

He added that Abdullah’s harsh criticism was intended more as a “wake-up call” and the fact that “the Saudis are on the same side [in supporting the Egyptian military] as the Israelis has emboldened them”.

Photo Credit: Analysts worry about the effect of Egypt’s ongoing crisis on U.S.-Saudi relations. Above, CNO Adm. Jonathan Greenert and Saudi Crown Prince Salman bin Abdulaziz in February. Credit: Official U.S. Navy Imagery/CC by 2.0

]]>via the Middle East Policy Council

It is a privilege to have been asked to join this discussion of Jacob Heilbrunn’s account of Israel’s fraying image. His article seems to me implicitly to raise two grim questions.

The first question is [...]]]>

via the Middle East Policy Council

It is a privilege to have been asked to join this discussion of Jacob Heilbrunn’s account of Israel’s fraying image. His article seems to me implicitly to raise two grim questions.

The first question is how long Israel can survive as a democracy or at all. The Jewish state has left the humane vision of early Zionism and its own beginnings far behind it. Israel now rules over a disenfranchised Muslim and Christian majority whom it would like to expel and a significant minority of disrespected secular and progressive Jews who are stealing away to the safer and more tolerant environs of the United States and other Western countries. Israel has befriended none of its Arab neighbors. It has spurned or subverted all their offers to accept and make peace with it except when compelled to address these by American diplomacy. The Jewish state has now largely alienated its former friends and supporters in Europe. Its all-important American patron and protector suffers from budgetary bloat, political constipation, diplomatic enervation, and strategic myopia.

The second question is what difference Israel’s increasing international isolation or withering away might make to Americans, including but not limited to Jewish Americans.

Let me very briefly speak to some of the issues that create these questions.

For a large majority of those over whom the Israeli state rules directly or indirectly, Israel is already not a democracy. It consists of four categories of residents: Jewish Israelis who, as the ruling caste, are full participants in its political economy; Palestinian Arab Israelis, who are citizens with restricted rights and reduced benefits; Palestinian Arabs in the West Bank, who are treated as stateless prisoners in their own land; and Palestinian Arabs in the Gaza ghetto, who are an urban proletariat besieged and tormented at will by the Israeli armed forces. The operational demands of this multi-layered, militarily-enforced system of ethno-religious separation have resulted in the steady contraction of freedoms in Israel proper.

Judaism is a religion distinguished by its emphasis on justice and humanity. American Jews, in particular, have a well-deserved reputation as reliable champions of the oppressed, opponents of racial discrimination, and advocates of the rule of law. But far from exhibiting these traditional Jewish values — which are also those of contemporary America — Israel increasingly exemplifies their opposites. Israel is now known around the world for the Kafkaesque tyranny of its checkpoint army in the Occupied Territories, its periodic maiming and slaughter of Lebanese and Gazan civilians, its blatant racial and religious bigotry, the zealotry and scofflaw behavior of its settlers, its theology of ethnic cleansing, and its exclusionary religious dogmatism.

Despite an ever more extensive effort at hasbara — the very sophisticated Israeli art of narrative control and propaganda — it is hardly surprising that Israel’s formerly positive image is, as Mr. Heilbrunn reports, badly “fraying.” The gap between Israeli realities and the image projected by hasbara has grown beyond the capacity of hypocrisy to bridge it. Israel’s self-destructive approach to the existential issues it faces challenges the consciences of growing numbers of Americans — both Jewish and non-Jewish — and raises serious questions about the extent to which Israel supports, ignores, or undermines American interests in its region. Many have come to see the United States less as the protector of the Jewish state than as the enabler of its most self-injurious behavior and the endower of the many forms of moral hazard from which it has come to suffer.

The United States has assumed the role of protecting power for Israel, which depends heavily on the ability of American Jews to mobilize subsidies, diplomatic and legal protection, weapons transfers, and other forms of material support in Washington. This task is made easier by the sympathy for Zionism of a large but silent and mostly passive evangelical Christian minority as well as lingering American admiration for Israelis as the pioneers of a vibrant new society in the Holy Land. It is noteworthy, however, that those actually lobbying for Israel are almost without exception Jewish. Their efforts exploit the unscrupulous venality and appeasement of politically powerful donors that are essential to political survival in modern America to assure reflexive fealty to Israel’s rightwing and its policies. When it’s not denying its own existence, the Israel Lobby boasts that it is the most effective special-interest advocate in the country. Official America’s passionate attachment to Israel has become a very salient part of U.S. political pathology. It epitomizes the ability of a small but determined minority to extract tax resources for its cause while blocking efforts to question these exactions.

Americans tend to resent aggressively manipulative behavior and have little patience with sycophancy. The ostentatious obsequiousness in evidence during Prime Minister Netanyahu’s address to Congress two years ago and the pledges of fealty to Israel of last year’s presidential campaign were a major turn-off for many. Mr. Netanyahu has openly expressed his arrogant presumption that he can manipulate America at will. Still, thoughtful Israelis and Zionists of conscience in the United States are now justifiably concerned about declining empathy with Israel in the United States, including especially among American Jews. In most European countries, despite rising Islamophobia, sympathy for Israel has already fallen well below that for the Palestinians. Elsewhere outside North America, it has all but vanished. An international campaign of boycott, disinvestment, and sanctions along the lines of that mounted against apartheid South Africa is gathering force.

Those who have lost the support of more than a passionate minority are often driven to defame and vilify those who disagree with them. Intimidation is necessary only when one cannot make a persuasive case for one’s position. As the case for the coincidence of American interests and values with those of Israel has lost credibility, the lengths to which Israel’s partisans go to denounce those who raise questions about Israel’s behavior have reached levels that invite ridicule, parody, melancholy, and disgust. The Hagel hearings evoked all four among many, plus widespread foreign derision and contempt. Mr. Hagel’s “rope-a-dope” defense may not have been elegant but it was as effective against bullying assault as nonviolent resistance usually is in the presence of observers with a commitment to decency. The American people have such a commitment and reacted as might be expected to their Senators’ overwrought busking for political payoffs.

Outside the United States, where narratives made in Israel do not rule the airwaves, the Jewish state has lost favor and is now widely denigrated. Israel’s bellicosity and contempt for international law evoke particular apprehension. Every war that Israel has engaged in since its creation has been initiated by it with the single exception of the Yom Kippur / Ramadan War of 1973, which was begun by Egypt. Israel is currently threatening to launch an unprovoked attack on Iran that it admits cannot succeed unless it can manipulate America into yet another Middle Eastern war. Many, if not most outside the United States see Israel as a major source of regional instability and — through the terrorism this generates — a threat to the domestic tranquility of any country that aligns with it.

To survive over the long term, Israel needs internationally recognized borders and peace with its neighbors, including the Palestinians. Achieving this has for decades been the major objective of U.S. diplomacy in the Middle East. But no effort to convince Israel to do what it must to make peace goes unpunished. Jimmy Carter’s tough brokering of normal relations between Israel, Egypt, and, ultimately, Jordan led to his disavowal by his own party. Barack Obama’s attempt to secure Israel’s acceptance in the Middle East led to his humiliation by Israel’s Prime Minister and his U.S. yahoos and flacks. The Jewish state loses no opportunity to demonstrate that it wants land more than it wants peace. As a result, there has been no American-led “peace process” worthy of the name in this century. Israel continues to ignore the oft-reiterated Arab and Islamic offer to normalize relations with it if it just does what it promised in the Camp David accords it would do: withdraw from the occupied territories and facilitate Palestinian self-determination.

Israel has clearly chosen to stake its future on its ability, with the support of the United States, to maintain perpetual military supremacy in its region. Yet, this is a formula with a convincing record of prior failure in the Middle East. It is preposterous to imagine that American military power can indefinitely offset Israel’s lack of diplomatic survival strategy or willingness to accommodate the Arabs who permeate and surround it. Successive externally-supported crusader kingdoms, having failed to achieve the acceptance of their Muslim neighbors, were eventually overrun by these neighbors. The power and influence of the United States, while still great, are declining at least as rapidly as American enthusiasm for following Israel into the endless warfare it sees as necessary to sustain a Jewish state in the Middle East.

The United States has made and continues to make an enormous commitment to the defense and welfare of the Jewish state. Yet it has no strategy to cope with the tragic existential challenges Zionist hubris and overweening territorial ambition have now forged for Israel. It is the nature of tragedy for the chorus to look on helplessly as a heroic figure with many admirable qualities is overwhelmed by faulty self-perception and judgment. The hammerlock that the Israeli right has on American discourse about the Middle East assures that America will remain an onlooker rather than an effective actor on matters affecting Israel, unable to protect Israel’s long-term interests or its own.

The outlook is therefore for continuing deterioration in Israel’s image and moral standing. This promises to catalyze discord in the United States as well as the progressive enfeeblement of American influence in the region and around the globe. Image problems are often symptoms of deeper existential challenges. By the time that Israel recognizes the need to make compromises for peace in the interest of its own survival, it may well be too late to bring this off. It would not be the first time in history that Jewish zealotry and suspicion of the bona fides of non-Jews resulted in the disappearance of a Jewish state in the Middle East. The collateral damage to the United States and to world Jewry from such a failure is hard to overstate. That is why the question of American enablement of shortsightedly self-destructive Israeli behavior needs public debate, not suppression by self-proclaimed defenders of Israel operating as thought police. And it is why Mr. Heilbrunn’s essay needs to be taken seriously not just as an investigation of an unpalatable reality but as a harbinger of very serious problems before both Israel and the United States.

These remarks were given during a luncheon seminar on Jacob Heilbrunn’s recent article in the May/June 2013 issue of The National Interest. Ambassador Freeman and Peter Berkowitz, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, joined Heilbrunn for this discussion. A summary of the event is available here.

]]>via IPS News

The Oslo peace process has failed and Europe must take stronger leadership in the Middle East, according to a distinguished group of former European leaders that is pushing for a stronger and more independent European stance on the Israeli occupation.

And some United States analysts believe the [...]]]>

via IPS News

The Oslo peace process has failed and Europe must take stronger leadership in the Middle East, according to a distinguished group of former European leaders that is pushing for a stronger and more independent European stance on the Israeli occupation.

And some United States analysts believe the European Union’s current leadership may heed the call.

A recent letter from the European Eminent Persons Group (EEPG) to the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs, Catherine Ashton, is deeply critical of both the EU’s and the United States’ approach to the Israel-Palestine conflict and calls for specific steps to try to save the two-state solution.

The letter was signed by 19 prominent Europeans – amongst them seven former foreign ministers, four former prime ministers and one former president – from 11 European countries, including the UK, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands and Latvia.

“We have watched with increasing disappointment over the past five years the failure of the parties to start any kind of productive discussion, and of the international community under American and/or European leadership to promote such discussion,” the letter said.

Specifically critical of the U.S.’s role, the letter also stated that President Barack Obama “…gave no indication [in his recent speech in Jerusalem] of action to break the deep stagnation, nor any sign that he sought something other than the re-start of talks between West Bank and Israeli leaders under the Oslo Process, which lost its momentum long ago.”

The EEPG criticised what they referred to as “the erasing of the 1967 lines as the basis for a two-state (solution).” They called for changes in EU policy and some specific steps to promote peace.

They called, among other points, for an explicit recognition that the Palestinian Territories are under occupation, imposing on Israel the legal obligations of that status; a clear statement that all Israeli settlements beyond the 1967 border be recognised as illegal and only that border can be a starting point for negotiations; and that the EU should actively support Palestinian reunification.

The notable leaders also called for “a reconsideration of the funding arrangements for Palestine, in order to avoid the Palestinian Authority’s present dependence on sources of funding which serve to freeze rather than promote the peace process,” an acknowledgment that the often praised “economic improvement” in the West Bank has been built on international donations and is not sustainable.

The timing of the letter, sent just after U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry’s most recent trip to the Middle East, was a clear statement that the EEPG does not believe the current round of U.S. diplomacy is likely to achieve significant progress. The letter has received only moderate publicity, yet EEPG’s co-chair, Sir Jeremy Greenstock, believes that the recommendations of the Group can get the long-dormant peace process back on track.

“We have had an acknowledgement from Ashton’s office to say that a response is being prepared,” Greenstock told IPS. “The letter recommends a strategic change, which is a big ask. The first step must be to start a more realistic debate about the poor results from recent policy. We then hope that our recommendations will get a good hearing.”

Greenstock also expressed confidence that EU leadership can not only contribute to reviving diplomacy but can also help the United States realign its policies toward a more productive track.

“The EEPG recognises that a U.S. role is indispensable,” he said. “But the current American stance is unproductive. We believe the Europeans can at least lead on exploring some alternatives, which could in the end be helpful to Washington.”

Hard-line pro-Israel voices have long insisted that only the United States should be mediating between Israel and the Palestinians. Elliott Abrams, a senior fellow for Middle Eastern studies at the Council on Foreign Relations and leading neo-conservative pundit, sharply criticised the letter in his blog.

“This letter is a useful reminder of European attitudes, at least at the level of the Eminent: Blame Israel, treat the Palestinians as children, wring your hands over the terrible way the Americans conduct diplomacy,” Abrams wrote.

“The Israelis will treat this letter with the derision it deserves, and the Palestinians will understand that because this kind of thing reduces European influence with Israel, the EU just can’t deliver much. Indeed it cannot, and the bias, poor reasoning, and refusal to face facts in this letter all suggest that that won’t be changing any time soon.”

But Paul Pillar, a professor in Georgetown University’s Security Studies Programme who spent 28 years as a CIA analyst, thinks Washington might welcome a European initiative along the lines suggested by the EEPG.

“I don’t think that European activism along this line would cause a great deal of heartburn, political or otherwise, in the White House,” Pillar told IPS. “Of course for the United States to take the sorts of positions mentioned in the letter would be anathema to the Israel lobby, and thus the United States will not take them.

“But it would be hard for the Israeli government or anyone else to argue that merely acquiescing in European initiatives is equivalent to the United States taking the same initiatives itself. If the EU were to get out in front in the way recommended by the EEPG, President Obama would say to Netanyahu and others – consistent with what he has said in the past, ‘I have Israel’s back and always will.

“But as I have warned, without peace we are likely to see other countries doing more and more things that challenge the Israeli position.’”

Chas Freeman, former U.S. Ambassador to Saudi Arabia and former president of the Middle East Policy Council, believes the EU has lost patience with U.S. policy in the Middle East and that Israel will soon need to contend with an EU that is more demanding than it has been in the recent past.

“The international community has long since lost confidence in American diplomacy in the Middle East,” Freeman told IPS. “Europe is not an exception, as shown in trends in voting at the United Nations. The ‘peace process’ was once the emblem of U.S. sincerity and devotion to the rule of law; it is now seen as the evidence of American diplomatic ineptitude, subservience to domestic special interests, and political hypocrisy. Europe no longer follows American dictates.

“The EU has its own divided mind. Israel must make its own case to Europeans now. That will not be easy.”

Greenstock believes the urgency of the moment can lead to firm European action. Asked why the EEPG members are taking bolder stances now than when they were in office, he said: “When most of the signatories were in office, there was still some hope that Oslo-Madrid could produce a result. Time and a lack of recent effective action has changed that. Almost every observer now thinks that the prospects for a two-state solution are fading. Hence the urgency.”

Photo: Um Abed plants an olive tree in support of Palestinian farmers. Credit: Eva Bartlett/IPS

]]>by Jasmin Ramsey

I wanted Iraq to dominate our postings this week, the 10th anniversary of the US invasion of the country. The work of Daniel, Jim and James received ample attention, though Americans don’t appear to have much of an appetite for remembering the disastrous [...]]]>

by Jasmin Ramsey

I wanted Iraq to dominate our postings this week, the 10th anniversary of the US invasion of the country. The work of Daniel, Jim and James received ample attention, though Americans don’t appear to have much of an appetite for remembering the disastrous decision that the war was. While nothing will do justice to the lives that the Iraq war took and irreparably damaged, I want to complete our coverage with the Iraq-focused portion of a jarring speech by Chas Freeman, a US diplomat and author who has decades of experience with the feats and failures of US foreign policy. Not more on Iraq, you may be thinking. After all, if you’re a regular reader of this blog, you’re undoubtedly more aware of the reality of the situation than the majority of Americans. But this is something different. Read ahead or listen to find out why. (The full text of Amb. Freeman’s speech, “Change without Progress in the Middle East”, is available here.)

Almost a decade ago, the United States invaded and occupied Iraq. Advocates of the operation assured us that this would be “a cakewalk” that would essentially pay for itself. The ensuing war claimed at least 6,000 American military and civilian lives. It wounded 100,000 U.S. personnel. It displaced 2.8 million Iraqis and – by conservative estimate – killed at least 125,000 of them, while wounding another 350,000. The U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq will ultimately cost American taxpayers at least $3.4 trillion, of which $1.4 trillion represents money actually spent by the Department of Defense, the Department of State, and intelligence agencies during combat operations; $1 trillion is the minimal estimate of future interest payments; and $1 trillion is future health care, disability, and other payments to the almost one million American veterans of the war.The only way to assess military campaigns is by whether they achieve their objectives. Outcomes – not lofty talk about a tangle of good intentions – are what count. In the case of Iraq, a fog of false narratives about weapons of mass destruction, connections to al Qaeda, threats to Iraq’s neighbors, and so forth left the war’s objectives to continuing conjecture. None of the goals implied by these narratives worked out. Instead, the war produced multiple “own goals.”Those who urged America into war claim Iraq was a victory for our country. If so, judging by results, the Bush administration’s objective must have been to assure the transfer of power in Iraq to the members of the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq, all of whom had spent the previous twenty years in the Islamic Republic of Iran. The former “Decider” made doubly sure of this outcome when Sunni and Shiite nationalist forces, like those of Sayyid Muqtada Al-Sadr, threatened the pro-Iranian politicians the United States had installed in Baghdad. Bush “surged” in additional troops to ensure that these politicians remained in office. And there they abide.

The neoconservative authors of the “surge” claim to have produced an important American victory through it. Certainly, in terms of its immediate objective of tamping down violent opposition to the regime, the “surge” was a tactical success. Still, one can only wonder about the sanity of people who argue that consolidating ethnic cleansing in Baghdad while entrenching a pro-Iranian government there represented a strategic gain for our country. The very same band of shameless ideologues, militarists, and armchair strategists who brought off that coup now clamor for an assault on Iran. One wonders why anyone in America still listens to them. Anywhere else, they would have been brought to account for the huge damage they have done.

If the United States invaded Iraq to demonstrate the capacity of our supremely lethal armed forces to reshape the region to our advantage, we proved the contrary. We never lost a battle, but we put the limitations of U.S. military power on full display.

If the purpose was to enhance U.S. influence in the Middle East, our invasion and occupation of Iraq helped bring about the opposite. Iraq is now for the most part an adjunct to Iranian power, not the balancer of it that it once was. Baghdad stands with Tehran in opposition to the policies of the United States and its strategic partners toward Bahrain, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria and Iran itself, including Iran’s nuclear programs. Iraq’s oil is now propping up the Assad regime in Syria. Iraq bought a big package of American weapons and training as we withdrew. But it’s already clear that its future arms purchases will come mainly from Russia and other non-American sources.

If the point was to prove that secular democracy is a viable norm in the Middle East, events in Iraq have borne savage witness to the contrary. The neoconservatives asserted with great confidence that the fall of a corrupt and tyrannical regime would pave the way for a liberal democratic government in Iraq. This was a profound misreading of history as well as Iraqi realities. The Salafist awakening and the sectarian conflagration kindled by our attempted rearrangement of Iraqi politics have not abated. Sectarian conflict continues to scorch Iraq and to lick away at the domestic tranquility of its Arab neighbors in both the Levant and the Gulf.

If the aim of our invasion and occupation of Iraq was to eliminate an enemy of Israel and secure the neighborhood for the Jewish state, we did not succeed. Israel’s adversaries were strengthened even as it made new enemies – for example, in Turkey – and began petulantly to demand that America launch yet another war to make it safe, this time against Iran. Mr. Netanyahu wants America to set red lines for Iran. Everyone else in the region wishes the United States would set red lines for Israel.

If the idea was to showcase the virtues of the rule of law and American-style civil liberties, then our behavior at Abu Ghraib, our denial of the protections of the Geneva Conventions to our battlefield enemies, and our suspension of habeas corpus (as well as many other elements of the Bill of Rights) at home put paid to that. These lapses from our constitution and the traditions of our republic have left us morally diminished. They have greatly devalued our credibility as international advocates of human freedoms everywhere, not just in the Middle East. We have few ideological admirers in the Arab or broader Islamic worlds these days. Our performance in Iraq is part of the reason for that.

All this helps to explain why most Americans don’t want to hear about Iraq anymore. A few weeks ago, the Congress failed to authorize funding for the continuation of the U.S. military training mission in Iraq, forcing the Pentagon to come up with the money internally. Almost no one here noticed.

On one level, the failure to fund a relationship with the Iraqi military through training represents a shockingly casual demonstration of the willingness of American politicians to write off the many sacrifices of our troops and taxpayers in our Iraq war. On another, it is an example of America’s most endearing political characteristic: our capacity for nearly instant amnesia. (“Iraq war? What Iraq war? You mean we sacrificed the lives and bodies of over one hundred thousand Americans and took on debt equivalent to one fourth of our GDP to occupy and refashion Iraq? Really? Why?”) They say the test for Alzheimer’s is whether you can hide your own Easter eggs. Apparently, we Americans can do that.

Failure is a much better teacher than success, but only if one is willing to reflect on what caused it. Our intervention in Iraq was a disaster for that country as well as for our own. It reshaped the Middle East to our disadvantage. Yet, we shy away from attempting to understand our fiasco even as those who led us into it urge us to reenact it elsewhere.

The military lessons we took away from Iraq have so far also proved hollow or false. When applied in Afghanistan, where we have now been in combat for more than eleven years, they haven’t worked. Analogies from other conflicts are not a sound basis for campaign plans, especially when they are more spin than substance. “In for a billion, in for half a trillion” is no substitute for strategy, let alone grand strategy.

Communities engaged in resistance to the imposition of government control where it has never before intruded do not see themselves as insurgents but as defenders of the established order. Counterinsurgency doctrine is irrelevant when there is no state with acknowledged legitimacy against which to rebel, no competent or credible government to buttress in power, and no politics untainted by venality, nepotism, and the drug trade to uphold. Pacification by foreign forces is never liberating for those who experience it. Foreign militaries cannot inject legitimacy into regimes that lack both roots and appeal in the communities they seek to govern.

Photo: English: US Marines cover each other as they prepare to enter one of Saddam Hussein’s palaces in Baghdad as they takeover the complex during Operation Iraqi Freedom. Credit: Lance Corporal Kevin C. Quihuis Jr. (USMC), 9 April 2003.

]]>Amb. Chas Freeman (ret.) spoke to a Middle East Policy Council (MEPC) forum on U.S. Grand Strategy — or, in his words “Grand Waffle” — in the Middle East on Capitol Hill yesterday and has graciously agreed to have the text posted on Lobe Log. Readers of the blog are already [...]]]>

Amb. Chas Freeman (ret.) spoke to a Middle East Policy Council (MEPC) forum on U.S. Grand Strategy — or, in his words “Grand Waffle” — in the Middle East on Capitol Hill yesterday and has graciously agreed to have the text posted on Lobe Log. Readers of the blog are already well acquainted with Freeman, a victim for 4 years, when he was appointed to chair the National Intelligence Council (NIC), of a McCarthyite-like campaign driven by many of the same neo-conservatives and Israel lobby activists opposed to Chuck Hagel’s nomination. Indeed, some of Hagel’s opponents, among them Bill Kristol, have tried to discredit the SecDef-designate through their alleged mutual association on the Atlantic Council board of directors, which Hagel has chaired since he left the Senate in 2009. (Paula Dobriansky, like Kristol, a second-generation neo-conservative, also served on that board at the same time, but Kristol conveniently omitted that fact.)

Freeman’s remarks point to, among other problems, fundamental contradictions in U.S. policy throughout the region, noting that those contradictions have become increasingly difficult to contain as public opinion has become increasingly relevant to the foreign policy of key states in the region as a result of the Arab Awakening, particularly in regard to relations with Israel and the continuing staunch support it receives from the U.S. He identifies his own “bottom line:”

The bottom line is this. U.S. policies of unconditional support for Israel, opposition to Islamism, and the use of drones to slaughter suspected Islamist militants and their families and friends have created an atmosphere that precludes broad strategic partnerships with major Arab and Muslim countries, though it does not yet preclude limited cooperation for limited purposes. The acceptance of Israel as a legitimate presence in the Middle East cannot now be achieved without basic changes in Israeli attitudes and behavior that are not in the offing.

Readers may want to watch the whole forum, which also included a slightly more optimistic Bill Quandt. The video is available at this link. Here are Freeman’s prepared remarks:

Grand Waffle in the Middle East — By Chas Freeman

Over the past half century or so the United States has pursued two main but disconnected objectives in West Asia and North Africa: on the one hand, Americans have sought strategic and economic advantage in the Arabian Peninsula, Persian Gulf, and Egypt; on the other, support for the consolidation of the Jewish settler state in Palestine. These two objectives of U.S. policy in the Middle East have consistently taken precedence over the frequently professed American preference for democracy.

These objectives are politically contradictory. They also draw their rationales from distinct moral universes. U.S. relations with the Arab countries and Iran have been grounded almost entirely in unsentimental calculations of interest. The American relationship with Israel, by contrast, has rested almost entirely on religious and emotional bonds. This disconnect has precluded any grand strategy.

Rather than seek an integrated policy framework, America has balanced the contradictions between the imperatives of its domestic politics and its interests. For many years, Washington succeeded in having its waffle in the Middle East and eating it too – avoiding having to choose between competing objectives. With wiser U.S. policies and more judicious responses to them by Arabs and Israelis, Arab-Israeli reconciliation might by now have obviated the ultimate necessity for America to prioritize its purposes in the region. But the situation has evolved to the point that choice is becoming almost impossible to avoid.The Middle East matters. It is where Africa, Asia, and Europe converge. In addition to harboring the greater part of the world’s conventionally recoverable energy supplies, it is a key passageway between Asia and Europe. No nation can hope to project its power throughout the globe without access to and through the Middle East. Nor can any ignore the role of the Persian Gulf countries in fueling the world’s armed forces, powering its economies, and setting its energy prices. This is why the United States has acted consistently to maintain a position of preeminent influence in the Middle East and to deny to any strategically hostile nation or coalition of nations the opportunity to contest its politico-military dominance of the region.The American pursuit of access, transit, and strategic denial has made the building of strategic partnerships with Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt a major focus of U.S. policy. The partnership with Iran broke down over three decades ago. It has been succeeded by antagonism, low-intensity conflict, and the near constant threat of war. The U.S. relationships with Egypt and Saudi Arabia are now evolving in uncertain directions. Arab governments have learned the hard way that they must defer to public opinion. This opinion is increasingly Islamist. Meanwhile, popular antipathies to the widening American war on Islamism are deepening. These factors alone make it unlikely that relations with the United States can retain their centrality for Cairo and Riyadh much longer.

The definitive failure of the decades-long American-sponsored “peace process” between Israelis, Palestinians, and other Arabs adds greatly to the uncertainty. Whether it yielded peace or not, the “peace process” made the United States the apparently indispensable partner for both Israel and the Arabs. It served dual political purposes. It enabled Arab governments to persuade their publics that maintaining good relations with the United States did not imply selling out Arab or Islamic interests in Palestine, and it supported the U.S. strategic objective of achieving acceptance for a Jewish state by the other states and peoples of the Middle East. Washington’s abandonment of this diplomacy was a boon to Israeli territorial expansion but a disaster for American influence in the region, including in Israel.