by Wayne White

In his Oct. 29 Foreign Policy article, “How We Won in Iraq”, General David Petraeus characterizes the 2003 US invasion and departure of US troops in 2011 as an American victory. This triumphant — though distorted — version of that searing saga seems acceptable to many Americans not [...]]]>

by Wayne White

In his Oct. 29 Foreign Policy article, “How We Won in Iraq”, General David Petraeus characterizes the 2003 US invasion and departure of US troops in 2011 as an American victory. This triumphant — though distorted — version of that searing saga seems acceptable to many Americans not only because it has been repeated so often, but also because it is so reassuring. Yet, despite the immense effort and sacrifice on the part of the US military and civilian personnel who served in Iraq, there are profound reasons to question such an upbeat conclusion.

Losers and winners

The Bush administration’s goal extended far beyond the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, and initially focused on the destruction of his alleged Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD). No WMD were found. The administration also planned to transform Iraq into a Western-style democracy that would function as a beacon to those suffering under nearby authoritarian regimes. Instead, even now Iraqis are saddled with an abusive, dysfunctional, non-transparent, corrupt, and sectarian-based government that resembles a democracy more in appearance than substance.

Rather than achieving a quick victory followed by a swift, orderly transition, the US became embroiled in a prolonged and bloody anti-insurgency campaign that cost well over 30,000 American casualties. The invasion also gave birth to al-Qaeda’s most damaging subsidiary, cost over $1 trillion, and for over five years diverted a huge amount of focus, military power, and spending from the important NATO effort in Afghanistan. Finally, instead of the US, the West, and moderate Arab states having considerable influence with Iraq’s new leaders, Baghdad’s most influential partner is Iran, and Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki is supporting the Assad regime in Syria.

As for the Iraqis, Sunni Arabs have been disenfranchised by the Shi’a-dominated successor regime, untold numbers of them have been killed, many of their communities have been ravaged by war, and well over a million were driven from their homes and businesses in the greater Baghdad area. A majority of Iraq’s roughly one million Christians have been forced to flee in the face of killings, church burnings and attacks on their businesses. Even the dominant Shi’a majority have suffered terrible casualties and great loss of property at the hands of the robust Sunni Arab insurgency back in 2003-2007, the depredations of their own rogue militias, and the drumfire of terrorist attacks and bombings on the part of al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) to this day.

For Arab Iraqis, insurgent sabotage and waves of looting following the invasion have devastated most of the country’s state industries, large private businesses, and all government ministries save one. Universities, hospitals, schools, banks, archives, much of Iraq’s electrical and oil infrastructure and the country’s rich archaeological heritage have also been severely damaged.

If there is a relative winner, it could be Iraq’s Kurdish community. Separated from the rest of the country by their own militias defending the borders of the Kurdish Autonomous Region (KRG), the majority of predominantly Kurdish areas have been spared the high levels of casualties and damage experienced elsewhere. In fact, the KRG now enjoys considerable prosperity (and more autonomy than at any time since the creation of the modern Iraqi state) with a host of Arab Iraqis taking advantage of Iraqi Kurdistan’s booming tourist industry every year to seek a respite from life farther south. Nevertheless, from late 1991 until Saddam Hussein’s overthrow in 2003, most of the Kurds now within the KRG already had been largely protected from Saddam’s rule within a northern sanctuary with much the same borders as the KRG.

The troop surge myth

Frontloaded prominently in Petraeus’ discussion of the “Surge of Ideas” is the new strategic approach he brought to the table. Petraeus’ shift toward increasingly embedding US troops within Iraqi communities and other tactical innovations was indeed more enlightened than the approach of his predecessors. Nonetheless, he does suggest strongly that the additional 30,000 US troops made a substantial difference. Yet, of the latter, only 5,000 were sent outside Baghdad to address severe problems in mainly Sunni Arab areas, so only in Baghdad was that reinforcement of any real significance.

Buried far below and evidently rated second to Petraeus’ “clear, hold and build” strategy was the US decision to exploit the so-called “Sunni Arab Awakening.” His description of the emergence of this phenomenon — the most critical game changer from late 2006 through 2008 — contains some notable errors.

First off, the decision on the part of many Sunni Arab insurgent and allied tribal leaders to seek a deal with American forces did not “begin several months before the surge” when one “talented US army brigade commander” decided to work with one “courageous Sunni sheikh” at Ramadi. The first Sunni Arab offer to cooperate with US forces — and in a far more sweeping manner — was brought to Washington’s attention in mid-2004, over two years before the events outside Ramadi in 2006. Senior military officers in the field at the time told me that other offers at least as significant as the one Petraeus cites occurred as early as 2003.

Petraeus is correct in his assertion that in 2003 many Sunni Arabs, despite their association with the former regime, still hoped to play a constructive role in the new Iraq. However, their offers of help were cast aside by the head of the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), Jerry Bremer, when he dismissed the entire Iraqi Army even while giving Petraeus writ to reach out locally in the latter’s northern 101st Airborne Division sector.

It is therefore wrong to place the blame for missing this opportunity exclusively on “Iraqi authorities in Baghdad” (who had precious little authority relative to Bremer’s at that point). In fact, senior US military officers on the scene acting on instructions (some pre-dating the invasion) recruited many thousands of Sunni Arab officers willing to remain in the Iraqi army to help maintain order; they also were waved off by Bremer.

Missed opportunities, lingering effects

In the summer of 2004, the US army and Marines fighting in various sectors west and northwest of Baghdad were approached by a number of insurgent and tribal leaders seeking a broad-based deal with US forces. They did not regard Iraqi forces as a significant foe, nor did they trust the largely Shi’a/Kurdish Iraqi central government. Yet, so serious were these Sunni Arab leaders about stopping the fighting with Coalition forces & turning against al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) that they agreed to meet with Iraqi Prime Minister Iyad Allawi in Tikrit, even though an agreement between the Sunni Arab leaders and Allawi could not be reached.

So, instead of grasping this outstretched hand that would have spared vast numbers of US and Iraqi casualties over the following two bloody years, the Bush administration deferred to an Iraqi government dominated by anti-Sunni Arab elements. Only when the uncontrollable maelstrom of bloodshed described by Petraeus erupted in early 2006 did the administration reluctantly decide to make the proverbial “deal with the devil.” This was driven by the need to gain some measure of traction in coping with a situation that had expanded to include the scourge of wholesale sectarian cleansing that displaced at least 1.5 million Iraqis and eradicated the once rich culture of mixed neighborhoods in Baghdad.

Once that decision had been made, the Sunni Arab “Awakening” deal took more than 100,000 insurgents off the battlefield and turned them into critical US assets against AQI. Only then could sufficient forces be freed up to crack down effectively on rampaging Shi’a militias — primarily Muqtada al-Sadr’s “Mahdi Army.”

Petraeus also wrongly paints al-Maliki as supportive of the deal with Sunni Arab combatants, albeit merely in Sunni Arab areas, in 2007. From my vantage point in US Intelligence, I watched as the Iraqi PM set about actively trying to torpedo the arrangement during 2007 — even going to the extreme of ordering a major Iraqi army attack on an Awakening force west of Baghdad (in a Sunni Arab area), thankfully headed off by US forces, in addition to other attempted attacks on specific “Awakening” commanders as well as the kidnapping of some of their relatives.

Petraeus rejects the notion that “we got lucky with the Awakening,” but that is, in fact, far closer to the truth because the “Awakening” emanated from Iraq’s Sunni Arab community — not from “a conscious decision” on the part of the US (save for a belated US decision to accept a deal that had been on the table for two years). Had the Bush administration instead continued to reject such a deal in 2007-08, US forces probably would not have had nearly such a decisive impact on the war — regardless of Petraeus’ otherwise more creative approach to the conflict. Conversely, had Washington allowed the deal to be accepted far earlier, Petraeus’ predecessor, Gen. George Casey, would have enjoyed a lot more success (despite a less savvy tactical approach).

Petraeus, nonetheless, is correct that welcoming — rather than spurning — Iraq’s Sunni Arabs is perhaps the only way out of the current escalating spiral of violence. Unfortunately, Maliki’s determination to minimize Sunni Arab political participation over the past four years especially has so poisoned the well of sectarian trust that it could be very difficult to achieve such a shift in policy so long as al-Maliki remains in power. It is, therefore, supremely ironic that after ignoring years of US entreaties to abandon his marginalization and persecution of Iraq’s Sunni Arabs and embrace reconciliation instead, al-Maliki should be meeting with President Obama today asking for American anti-terrorism assistance to address the violence he and his cronies have done so much to provoke.

]]>by James A. Russell

The confirmation hearings of John Brennan for director of the Central Intelligence Agency serve as the latest searing reminder of the intellectual rigamortis gripping the national security establishment and how brain dead we have become as a country in addressing strategy and strategic issues.

The sole focus [...]]]>

by James A. Russell

The confirmation hearings of John Brennan for director of the Central Intelligence Agency serve as the latest searing reminder of the intellectual rigamortis gripping the national security establishment and how brain dead we have become as a country in addressing strategy and strategic issues.

The sole focus of these hearings has been the country’s ongoing love affair with targeted assassinations carried out by drones against our Islamic extremist adversaries.

Instead of engaging in a real debate over the efficacy of these assassinations as an element of counter-terrorism strategy, we are left with the voices of Republicans who see nothing wrong with the state drawing up its monthly assassination lists and those of Democrats who worry about civil rights issues and want judges to review who the government proposes to assassinate each month.

If ever there was an example of tactics in search of a strategy, this is it. Sadly, this is only the latest example of the national security establishment confusing the two.

This country has witnessed the substitution of tactics for strategy during the last decade as a series of military and civilian leaders have trumpeted the benefits of “counterinsurgency strategy” as the correct approach to our wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Yet counterinsurgency is nothing more than a tactical approach on the battlefield, which, by the way, has mostly failed miserably when attempted by western militaries over the last century. It is not a strategy.

Killing terrorists by whatever means is also tactics masquerading as strategy — just like counterinsurgency. Our focus on assassinating suspected terrorist foes both by hellfire missiles from above and by Special Forces kicking in doors on the ground in fact reflects a specific approach to counter-terrorism called leadership decapitation. You won’t hear this mentioned in the hearings — but this is the strategic issue under discussion, without, of course, being discussed.

Leadership decapitation as a strategy is short-sighted, bound to ultimately fail, and may in fact increase threats to our country. What is the evidence to support this assertion and where has leadership decapitation been tried? The answer exists in almost every irregular war undertaken by occupying armies over the last century. The French perfected the technique during their occupation of Algeria in one celebrated example, though that war didn’t turn out well for them. Another current day example is Israel, which has routinely assassinated its adversaries in its futile attempt to prevent terrorist attacks over the last 60 years. Just as the French could not kill their way to victory in Algeria, Israel cannot kill its way to peace and security.

Although you might not realize it, the United States is by far the greatest modern day practitioner of leadership decapitation. How has this strategy worked out for us and why isn’t Brennan being asked about it in his confirmation hearings?

I recall sitting in on a briefing in Afghanistan back in 2010 and seeing the obligatory power point slide with all the red “X’s” through the Taliban’s leadership structure in the province I was visiting. Stupidly, of course, I mentioned to the briefer: “Well, we must be winning, then.” He laughed and responded: “You could have shown up here for every year for the last few years and seen the exact same slide. They just keep coming back.”

Therein lies the problem. The US has implemented the tactic of leadership decapitation on an industrial scale in Afghanistan over the last three years under the military leadership of General Stanley McChrystal and then his successor, David Petraeus. Both unleashed the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) in Afghanistan just as they did in Iraq. In Iraq during 2007 and 2008, JSOC killed many Iraqis, which helped cover the US retreat but that’s about it. JSOC teams and the CIA drone mavens have also killed a lot of the Taliban, but has the Taliban given up?

Setting aside the moral and ethical issues related to state assassinations of people without due process, the broader strategic issue remains — we can’t kill our way out of disputes with Islamic militants that are currently on the receiving end of our hellfire missiles. They will keep coming back until a political settlement is reached or until they are all dead. Since we can’t kill them all, the war will go on.

Still worse, by intervening in what are essentially local political disputes in countries like Yemen, Mali and Afghanistan, we run the risk of provoking exactly the kind of attacks against us that we are supposed to be trying to forestall.

Leadership decapitation is a prescription for never ending war, which may be useful for political purposes in some US quarters (like it is in Israel), but remains a terrible strategy. Just ask the Israelis how it has worked out for them. Despite the comforting illusion of the cost-free, push-button war offered by our standoff drone strikes and our darkly clad soldiers jumping out of helicopters to gun down suspected terrorists, we are playing a dangerous game that may only increase threats to this country.

As much as we might want to believe otherwise, there is no military solution to the political problem of extremist violence. It is a square peg being inserted into a round hole. Al Qaeda-inspired militancy around the Islamic world is at heart a violent protest against modernity that commands no broadly based popular political support. Do we see Saudi citizens (or any citizens, anywhere, for that matter) mounting the barricades in a revolution supporting Al Qaeda’s call for a return to the caliphate? We should let Al Qaeda die its natural death. If anything, America’s military interventions in the developing world have prolonged the relevance of the handful of militants flocking to this banner.

At the very least, sound strategic thinking would deliver us the kind of debate that is so desperately needed on the strategic choices facing this country as we try to decide how best to protect ourselves. The recent confirmation hearings offered us the chance to explore these issues, but the silence from both the executive and legislative branches is deafening.

This country is tumbling into a de facto era of apparently endless drone wars with no critical assessment or alternative views being offered. It’s hard not to draw the parallel to Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, with the United States ceaselessly lobbing missiles into an unpoliceable, dark, and impenetrable interior just as the ship did in Conrad’s story — firing away futilely at unseen targets in a world gone mad.

]]>By James A. Russell

As the Senate prepares for what will be contentious confirmation hearings for Chuck Hagel to be the next Secretary of Defense, it is important to debunk some of the popularized narratives that are being offered by neoconservative commentators as they attempt to seize control of important issues [...]]]>

By James A. Russell

As the Senate prepares for what will be contentious confirmation hearings for Chuck Hagel to be the next Secretary of Defense, it is important to debunk some of the popularized narratives that are being offered by neoconservative commentators as they attempt to seize control of important issues that will likely come up during the confirmation process.

Hagel was one of the few who had the guts to question the Iraq invasion when it was politically unpopular to do so, was right about the disastrous consequences of the invasion for US power and prestige, and rightly raised questions about the increase in troop levels committed as part of the so-called “surge” in 2007. As noted by Wayne White in this blog, there are many misconceptions and myths perpetrated about the surge and its relationship to America’s experience in the war.

Neoconservative commentators have successfully shaped a popular narrative suggesting that the surge helped spur the famous Anbar Awakening that turned the tide in Iraq and somehow helped “win” the war. There are grains of truth in these assertions, but these half-truths have been used to support wholly unfounded and full-blown myths that are still spouted in print by columnists like Charles Krauthammer, Elliott Abrams and others.

My book on ground operations in Iraq from 2005-07 in Anbar and Mosul deals extensively with local politics in Anbar during the period and provides an entirely different picture of the awakening and its circumstances that had little to do with the surge. Like all complex phenomena, the awakening occurred in a particular context and with a history that has been largely omitted from popular narratives about the war.

The first of the so-called tribal “flips” started in 2005 in Al Qaim due in part to a dispute involving the Albu Mahal tribe and its interest in controlling border and smuggling operations. The Albu Mahals subsequently became the “desert protector” force in 2005; Marines issued them uniforms and installed them in local police stations to start directing traffic and performing other constabulary duties. In a pattern that would be repeated elsewhere around the province, the Marines turned a blind eye to the Albu Mahal’s smuggling operations in exchange for this support — so long as the smuggling did not support insurgent activities. The Marines initially tried to set up local militias in 2004 in the city of Hit in Anbar — efforts that failed miserably as the units disintegrated when insurgents attacked them.

The Awakening spread from western Anbar in 2005 and culminated in Ramadi in the summer/fall of 2006 — before the surge had even begun. By the time the surge happened in the spring of 2007, there were already over 1,000 former Sunni tribal and nationalist insurgents manning police checkpoints in and around Ramadi.

The tribal flip had to do with many factors – national-level political developments and the rising power of the Shi’ites and the realization by Sunni tribal leaders that only the US could protect them from the ascendant Shi’ites. They grasped the obvious in late 2006: their continued alliance with the jihadists would lead to their destruction. They had also become disaffected with the non-Iraqi jihadists and their brutal methods of intimidation. They also resented the way these jihadists had seized control over the smuggling routes in Anbar that had supported Sunni tribes for decades.

In the fall of 2006, US commanders in Ramadi stood by as the 1920s Brigade and other Sunni nationalist insurgents dragged the jihadists out of the mosques on Fridays and blew their brains out. Importantly, the improved tactical proficiency of US units — a proficiency driven by desperation and willingness to learn and adapt — played a role in supporting the awakening process. US brigade and battalion commanders deserve great credit for forming personal relationships with tribal leaders like Abdul Sittar Abdu Risha that helped immeasurably as the awakening process gathered momentum in the fall of 2006.

Contrary to popular myths now being offered up on the airwaves, the White House and Gen. David Petraeus were not involved in decisions by brigade and battalion commanders to start forming these local alliances. My research on this period of the war shows that these commanders took these steps out of desperation and because they couldn’t think of anything else to do to reduce insurgent violence.

Many myths surround the Awakening and the surge – myths popularized by the neocons and the mainstream media, as well as by fawning narratives in books by Paula Broadwell and others about how brilliant senior leaders engineered this change in the landscape of Iraq. Like all narratives, however, their stories contain only grains of truth.

The increase in US troop numbers were important in tamping down violence in Iraq, and the bloody and brutal campaign undertaken by the Joint Special Operations Command in 2007 in Baghdad eviscerated the insurgent networks in and around the capital. But, the surge was not responsible for the Awakening and it did not “win” the war, as asserted by the neoconservatives.

The net result of the surge was to help create circumstances to cover the US retreat so the neoconservatives and others could assert we had in fact achieved something worthwhile in Iraq. The problem with this is that there are still those out there that believe the information operations (IO) campaign that was itself part of the surge. We ended up believing our own invented press releases — a process now repeating itself in Afghanistan.

This IO campaign regrettably succeeded, and there is today no national-level debate over the disastrous US experience in Iraq. That absence means that columnists like Krauthammer and other neocons can make unsupported and unchallenged assertions about the “surge” and its circumstances.

Importantly, it means that the same neoconservative figures who helped sell the Iraq war in the first place can also, with straight faces, go after figures like Chuck Hagel, who, whatever his faults, turned out to be right about Iraq. If Hagel was right about Iraq, maybe it says something about other judgments he might have to make as our next secretary of defense.

Maybe this country would be better off with senior leaders willing to take politically unpopular positions on important questions and have the strength of their convictions to carry those arguments into the senior reaches of government.

– James Russell serves as an associate professor in the Department of National Security Affairs at the Naval Post-Graduate School in Monterey, Ca. The views in this article are his alone.

Photo: President George W. Bush makes a statement to reporters about the war in Iraq after his meeting with senior national defense leaders at the Pentagon May 10, 2007. DoD photo by Staff Sgt. D. Myles Cullen, U.S. Air Force.

]]>Criticism of former Senator Chuck Hagel for not backing the 2007 US “troop surge” in Iraq demands an explanation of why that relatively small reinforcement was not the main driver for reversing Iraq’s descent into violent chaos. In fact, when proposed in late 2006, there was widespread doubt about its potential [...]]]>

Criticism of former Senator Chuck Hagel for not backing the 2007 US “troop surge” in Iraq demands an explanation of why that relatively small reinforcement was not the main driver for reversing Iraq’s descent into violent chaos. In fact, when proposed in late 2006, there was widespread doubt about its potential for success among experts. And that skepticism was not, as detractors allege, off target. In reality, a different change in Bush Administration Iraq policy was the primary game-changer. Nonetheless, widespread belief still persists that the troop surge alone reversed the downward spiral in Iraq during 2003-2006. Some have tried to correct the record, but without much success.

When I served with the Iraq Study Group (ISG) led by former Secretary of State James Baker and former Congressman Lee Hamilton in 2006, many of its core Middle East experts felt the “troop surge” would fail because it was far too small. It increased US troops in Iraq by less than 20 percent. The situation, which included the robust Sunni Arab insurgency, widespread al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) terrorism and rampant sectarian cleansing, had gotten too far out of control for so few troops to make a real difference. Some believed as many as five times the 21,500 troops the Bush Administration sent in were needed. After all, troop levels had risen and fallen modestly before with little change in what had been a grindingly indecisive anti-insurgency war.

Unknown to the ISG (and evidently most of everyone outside the executive branch) the Bush Administration had quietly made another decision truly capable of sparking a major improvement on the ground in Iraq. The White House agreed to a deal with the bulk of the Sunni Arab insurgents fighting US forces. The insurgents not only wanted to stop fighting US/UK forces, but also to partner with Coalition forces against al-Qaida in Iraq. Although holding their own and inflicting heavy casualties, the insurgents had tired of suffering heavy losses themselves, were appalled by damage to their own communities from the fighting, and had been angered by extremist AQI abuses in their home towns and villages.

In fact, insurgent leaders began approaching US forces over two years earlier with the same offer. But it was rebuffed by the Bush Administration (despite the support of many US military officers in Iraq) because the Shi’a-dominated Iraqi government bitterly opposed such a deal. In late 2006, however, in the face of a severe spike in violence — and despite more objections from the Iraqi government — the US accepted the deal. That triggered what was called Iraq’s Sunni Arab “Awakening” (up to 100,000 Sunni Arab insurgents changing sides).

It took nearly two more years of hard fighting to bring most all Sunni Arab insurgents into the arrangement, weaken the power of AQI, and curb sectarian cleansing. The modest US “troop surge” improved tactics set in motion by General David Petraeus, and gains in Iraqi Army professionalism helped too, but these were not nearly as critical as what some called the far more sweeping “deal with the devil.”

Sadly, Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, who objected to the deal well into 2008, continues to exclude the Sunni Arab community from the Iraqi political mainstream. Despite assurances to the contrary, he has hounded many Sunni Arab fighters who took part in the “Awakening”, arresting and even taking out a good number of them. This has soured Sunni Arabs on Maliki and his Shi’a allies, causing enough Sunni Arabs to resume assisting AQI to make it difficult to stop the lethal bombings.

Why the decision to make this deal with the vast majority of the insurgents was withheld from the Iraq Study Group (and others) is unknown to me. It almost surely would have changed our recommendations, and likewise might well have made lawmakers like Chuck Hagel less skeptical of what otherwise appeared to be an inadequate fix in the face of a far greater challenge.

Equally bizarre has been the sloppy use of the US “troop surge” by most American media outlets as misleading shorthand for everything that altered the Iraqi playing field back in 2007-2008. As a result, critics continue to hound opponents (like Hagel) about a troop surge that could well have been a military failure if not for the stunning, belated, and initially secretive deal that transformed most of our Sunni Arab foes in Iraq into American allies.

Photo: US Army soldiers move down a street as they start a clearing mission in Dora, Iraq, on May 3, 2007. Soldiers from the 2nd Platoon, Alpha Company, 2nd Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment, 3rd Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division are patrolling the streets in Dora. DoD photo by Spc. Elisha Dawkins, US Army. (Released)

]]>The grandfather of the 16-year-old American-Yemeni boy who was killed by a CIA drone strike in Yemen last year is suing 4 US officials, including Defense Secretary Leon Panetta and Former CIA Director David Petraeus, over his son and grandson’s deaths.

The father of the Colorado-born Abdulrahman al Awlaki’s was an al [...]]]>

The grandfather of the 16-year-old American-Yemeni boy who was killed by a CIA drone strike in Yemen last year is suing 4 US officials, including Defense Secretary Leon Panetta and Former CIA Director David Petraeus, over his son and grandson’s deaths.

The father of the Colorado-born Abdulrahman al Awlaki’s was an al Qaeda leader. Rights groups and reporters have argued that the boy was extrajudicially killed for his father’s actions. The fact that he was an American civilian killed by the US military in a country with which Washington is not at war also raised legal and ethical questions.

But Americans appear to favor drone strikes over all. A February 2012 Washington Post/ABC poll says 83 percent of Americans support drone strikes and 79 percent approve even when US citizens are targeted. Interestingly, Americans appear far less supportive of drone technology used for domestic law enforcement targeting citizens.

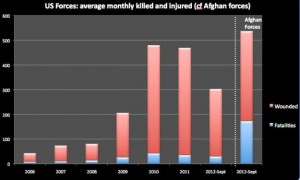

]]>Foreign Policy’s Stephen Walt highlights a chart by Belfer Center fellow Matt Waldman showing that as the US-led 2009 “Surge” in Afghanistan proceeded, US casualties increased. The pace in 2012 is also roughly similar to the toll from the previous two years:

Equally important, the final column (based on figures [...]]]>

Foreign Policy’s Stephen Walt highlights a chart by Belfer Center fellow Matt Waldman showing that as the US-led 2009 “Surge” in Afghanistan proceeded, US casualties increased. The pace in 2012 is also roughly similar to the toll from the previous two years:

Foreign Policy’s Stephen Walt highlights a chart by Belfer Center fellow Matt Waldman showing that as the US-led 2009 “Surge” in Afghanistan proceeded, US casualties increased. The pace in 2012 is also roughly similar to the toll from the previous two years:

Equally important, the final column (based on figures reported by Simon Klingert) suggests that the Taliban’s ability to inflict casualties on Afghan security forces (ANSF) remains undiminished. Given that U.S. hopes of a “soft landing” following withdrawal depend on the ANSF taking up the fight themselves, this does not augur well for Afghanistan’s post-American future.

Michael Cohen meanwhile argues in the Guardian that General David Petraeus’s fatal flaw was not his extramarital affair (which he will forever remembered for) but his surge strategy in Afghanistan:

]]>Petraeus was wrong – badly wrong. And more than 1,000 American soldiers, and countless more Afghan civilians, have paid the ultimate price for his over-confidence in the capabilities of US troops. And it wasn’t as if Petraeus was an innocent bystander in these discussions: he was working a behind-the-scenes public relations effort – talking to reporters, appearing on news programs – to force the president’s hand on approving a surge force for Afghanistan and the concurrent COIN strategy.

But when he took over as commander of the Afghanistan war in 2010, Petraeus adopted the harsh military strategy that he’d claimed the new, more civilian-focused COIN military plan would eschew. He ramped up airstrikes, which led to more civilian deaths. He increased the use of special forces operations. Perhaps worst of all, he sought to hinder the implementation of a political strategy for ending the war, seeking, instead, a clear military victory against the Taliban.

The greatest indictment of Petraeus’s record is that, 18 months after announcing the surge, President Obama pulled the plug on a military campaign that had clearly failed to realize the ambitious goals of Petraeus and his merry team of COIN boosters. Today, the Afghanistan war is stalemated with little hope of resolution – either militarily or politically – any time soon. While that burden of failure falls hardest on President Obama, General Petraeus is scarcely blameless. Yet, to date, he has almost completely avoided examination for his conduct of the war in Afghanistan.

History, it is said, arrives first as tragedy, then as farce. First as Karl Marx, then as the Marx Brothers. In the case of twenty-first century America, history arrived first as George W. Bush (and Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld and [...]]]>

History, it is said, arrives first as tragedy, then as farce. First as Karl Marx, then as the Marx Brothers. In the case of twenty-first century America, history arrived first as George W. Bush (and Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld and Paul Wolfowitz and Douglas Feith and the Project for a New America — a shadow government masquerading as a think tank — and an assorted crew of ambitious neocons and neo-pundits); only later did David Petraeus make it onto the scene.

It couldn’t be clearer now that, from the shirtless FBI agent to the “embedded” biographer and the “other other woman,” the “fall” of David Petraeus is playing out as farce of the first order. What’s less obvious is that Petraeus, America’s military golden boy and Caesar of celebrity, was always smoke and mirrors, always the farce, even if the denizens of Washington didn’t know it.

Until recently, here was the open secret of Petraeus’s life: he may not have understood Iraqis or Afghans, but no military man in generations more intuitively grasped how to flatter and charm American reporters, pundits, and politicians into praising him. This was, after all, the general who got his first Newsweek cover (“Can This Man Save Iraq?”) in 2004 while he was making a mess of a training program for Iraqi security forces, and two more before that magazine, too, took the fall. In 2007, he was a runner-up to Vladimir Putin for TIME’s “Person of the Year.” And long before Paula Broadwell’s aptly named biography, All In, was published to hosannas from the usual elite crew, that was par for the course.

You didn’t need special insider’s access to know that Broadwell wasn’t the only one with whom the general did calisthenics. The FBI didn’t need to investigate. Even before she came on the scene, scads of columnists, pundits, reporters, and politicians were in bed with him. And weirdly enough, many of them still are. (Typical was NBC Nightly News anchor Brian Williams mournfully discussing the “painful” resignation of “Dave” — “the most prominent and best known general of the modern era.”) Adoring media people treated him like the next military Messiah, a combination of Alexander the Great, Napoleon, and Ulysses S. Grant rolled into one fabulous piñata. It’s a safe bet that no general of our era, perhaps of any American era, has had so many glowing adjectives attached to his name.

Perhaps Petraeus’s single most insightful moment, capturing both the tragedy and the farce to come, occurred during the 2003 invasion of Iraq. He was commanding the 101st Airborne on its drive to Baghdad, and even then was inviting reporters to spend time with him. At some point, he said to journalist Rick Atkinson, “Tell me how this ends.” Now, of course, we know: in farce and not well.

Here was the odd thing: none of David Petraeus’s “achievements” outlasted his presence on the scene. Still, give him credit. He was a prodigious campaigner and a thoroughly modern general. From Baghdad to Kabul, no one was better at rolling out a media blitzkrieg back in the U.S. in which he himself would guide Americans through the fine points of his own war-making.

Where, once upon a time, victorious commanders had to take an enemy capital or accept the surrender of an opposing army, David Petraeus conquered Washington, something even Robert E. Lee couldn’t do. Until he made the mistake of recruiting his own “biographer” (and lover), he proved a PR prodigy. He was, in a sense, the real life military version of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Jay (“the Great”) Gatsby, a man who made himself into the image of what he wanted to be and then convinced others that it was so.

In the field, his successes were transitory, his failures all too real, and because he proved infinitely adaptable, none of it really mattered or stanched the flood of adjectives from admirers of every political stripe. In Washington, at least, he seemed invincible, even immortal, until it all ended in a military version of Dallas or perhaps previews for Revenge, season three.

His “fall from grace,” as ABC’s nightly news labeled it, was a fall from Washington’s grace, and his tale, like that of the president who first fell in love with him, might be summarized as all-American to fall-American.

Turning the Lone Superpower Into the Lonely Superpower

David Petraeus was a Johnny-come-lately in respect to Petraeus-ism. He would pick up the basics of the imperial style of that moment from his models in and around the Bush administration and apply them to his own world. It was George W. and his guys (and gal) who first dreamed the dreams, spent a remarkable amount of time “conquering Washington,” and sold their particular set of fantasies to themselves and then to the American people.

They were the original smoke-and-mirrors crew. From the moment, just five hours after the 9/11 attacks, that Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld — in the presence of a note-taking aide – urged planning to begin against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq (“Go massive. Sweep it all up. Things related and not…”), the selling of an invasion and various other over-the-top fantasies was underway.

First, in the heat of 9/12, the president and top administration officials sold their “war” on terror. Then, after “liberating” Afghanistan and deciding to stay for the long run, they launched a massive publicity campaign to flog the idea that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction and was linked to al-Qaeda. In doing so, they would push the image ofmushroom clouds rising over American cities from the Iraqi dictator’s nonexistent nuclear program, and chemical or biological weapons being sprayed over the U.S. East Coast by phantasmal Iraqi drones.

Cheney and Rice, among others, would make the rounds of the talk shows, putting the heat on Congress. Administration figures leaked useful (mis)information, pressed the CIA to cherry-pick the intelligence they wanted, and even formed their own secret intel outfit to give them what they needed. They considered just when they should roll out their plans for their much-desired invasion and decided on September 2002. As White House Chief of Staff Andrew Card infamously explained, “From a marketing point of view, you don’t introduce new products in August.”

They were, by then, at war — in Washington. Initially, they hardly worried about the actual war to come. They were so confident of what the U.S. military could do that, like the premature Petraeuses they were, they concentrated their efforts on the homeland. Romantics about U.S. military power, convinced that it would trump any other kind of power on the planet, they assumed that Iraq would be, in the words of one of their supporters, a “cakewalk.” They convinced themselves and then others that the Iraqis would greet the advancing invaders as liberators, that the cost of the war (especially given Iraq’s oil wealth) would be next to nothing, and that there was no need to create a serious plan for a post-invasion occupation.

In all of this, they proved both masters of public relations and staggeringly wrong. As such, they would be the progenitors of an imperial tragedy — a deflating set of disasters that would take the pop out of American power and turn the planet’s “lone superpower” into a lonely superpower presiding over an unraveling global system, especially in the Greater Middle East. Blinded by their fantasies, they would ensure a more precipitous than necessary American decline in the first decade of the new century.

Not that they cared, but they would also generate a set of wrenching human tragedies: first for the Iraqis, hundreds of thousands of whom became casualties of war, insurgency, and sectarian strife, while millions more fled into exile; then there were the Afghans, who died attendingweddings, funerals, even baby-naming ceremonies; and, of course, tens of thousands of U.S. soldiers and contractors, who died or were injured, often grievously, in those dismal wars; and don’t forget the inhabitants of post-Katrina New Orleans left to rot in their flooded city; or the millions of Americans who lost jobs, houses, even lives in the economic meltdown of 2008, a disaster that emerged from a set of globe-spanning financial fantasies and snow jobs that Bush and his crew encouraged and facilitated.

They were the ones, in other words, who took a mighty imperial power already in slow decline, grabbed the wheel of the car of state, put the peddle to the metal, and like a group of drunken revelers promptly headed for the nearest cliff. In the process — they were nothing if not great salesmen — they sold Americans a bill of goods, even as they fostered their own dreams of establishing a Pax Americana in the Greater Middle East and aPax Republicana at home. All now, of course, down in flames.

They were the ones, in other words, who took a mighty imperial power already in slow decline, grabbed the wheel of the car of state, put the peddle to the metal, and like a group of drunken revelers promptly headed for the nearest cliff. In the process — they were nothing if not great salesmen — they sold Americans a bill of goods, even as they fostered their own dreams of establishing a Pax Americana in the Greater Middle East and aPax Republicana at home. All now, of course, down in flames.

In his 1987 Princeton dissertation, David Petraeus wrote this on perception: “What policymakers believe to have taken place in any particular case is what matters — more than what actually occurred.” On this and other subjects, he was certainly no dope, but he was a huckster — for himself (given his particular version of self-love), and for a dream already going down in Iraq and Afghanistan. And he was just one of many promoters out there in those years pushing product (including himself): the top officials of the Bush administration, gaggles of neocons, gangs of military intellectuals, hordes of think tanks linked to serried ranks of pundits. All of them imagining Washington as a battlefield for the ages, all assuming that the struggle for “perception” was on the home front alone.

Producing a Bedside Manual

You could say that Petraeus fully arrived on the scene, in Washington at least, in that classic rollout month of September (2004). It was then that the three-star general, in charge of training Iraq’s security forces, gave a president in a tight race for reelection a little extra firepower in the domestic perception wars. Stepping blithely across a classic no-no line for the military, hewrote a well-placed op-ed in the Washington Post as General Johnnie-on-the-spot, plugging “tangible progress” in Iraq and touting “reasons for optimism.”

Given George W. Bush’s increasingly dismal and unpopular mission-unaccomplished war and occupation, it was like the cavalry riding to the rescue. It shouldn’t have been surprising, then, that the general, backed and promoted in the years to come by various neocon warriors, would be the military man the president would fall for. Over the first half of the “surge” year of 2007, Bush would publicly cite the general more than 150 times, 53 in May alone. (And Petraeus, a man particularly prone toward those who idolized him — see: Broadwell, Paula — returned the favor.)

But there was another step up the ladder of perception that would make him the perfect neocon warrior. While commanding general at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in 2005-2006, he also became the “face” of a new doctrine. Well, actually, a very old and particularly dead doctrine that went by the name of counterinsurgency or, acronymically, COIN. It had been part and parcel of the world of colonial and neocolonial wars and, in the 1960s, became the basis for the U.S. ground war and “pacification” program in South Vietnam — and we all know how that turned out.

Amid the greatest defeat the U.S. had suffered since the burning of Washington in 1814, counterinsurgency as a doctrine was left for dead in the rubble of Vietnam. With a sigh of relief, the military high command turned back to the task of stopping Soviet armies-that-never-would from pouring through Germany’s Fulda Gap. Even in the military academies they ceased to teach counterinsurgency — until Petraeus and his team disinterred it, dusted it off, polished it up, and turned it into the military’s latest war-fighting bible. Via a new Army and Marine field manual Petraeus helped to oversee, it would be presented as the missing formula for success in the Bush administration’s two flailing, failing invasions-cum-occupations on the Eurasian mainland.

It would gain such acclaim, in fact, that the University of Chicago Press would publish it as a trade paperback on July 4, 2007. Already back in Baghdad filling the role of Washington’s savior, the general, who had already written a foreward for that “paradigm shattering” manual, would flog it with this classic blurb: “Surely a manual that’s on the bedside table of the president, vice president, secretary of defense, 21 of 25 members of the Senate Armed Services Committee, and many others deserves a place at your bedside too.”

And really, you know the rest. He would be sold (and, from Baghdad, sell himself) to the public the same way Saddam’s al-Qaeda links and weapons of mass destruction had been. He, too, would be rolled out as a product — our “surge commander” — and soon enough become the general of the hour, and Iraq a success story for the ages. Then, appointed CENTCOM commander, the military man in charge of Washington’s two wars, by Bush, he made it out of town before it became fully apparent that his successes in Iraq would leave the U.S. out on its ear a few years down the line.

The Fall of the American Empire (Writ Small)

Afghanistan followed as he maneuvered to box a new president, Barack Obama, into a new “surge” in another country. Then, his handpicked war commander General Stanley McChrystal, newly minted COIN believer, “ascetic,” and “rising superstar” (who wouldundergo his own Petraeus-like media build-up), went down in shame over nasty commentsmade by associates about the Obama White House. In mid-2010, Petraeus would take McChrystal’s place to save another president by bringing COIN to bear in just the right way. The usual set of hosannas — and even less success than in Iraq — followed.

But as with Saddam Hussein’s mythical WMDs, it seemed scarcely to matter when there was no there there. Even though Afghanistan’s two COIN commanders had visibly failed in a war against an under-armed, undermanned, none-too-popular minority insurgency, and even though the doctrine of counterinsurgency would soon be tossed off a moving drone and left to die in the Afghan rubble, Petraeus once again made it out in one piece. In Washington, he was still hailed as the soldier of his generation and President Obama, undoubtedly fearing him in 2012, either as a candidate or a supporter of another Republican candidate, promptly stashed him away at the CIA, sending him safely into the political shadows.

With that, Petraeus left his four stars behind, shed COIN-mode just as his doctrine was collapsing completely, and slipped into the directorship of a militarizing CIA and its drone wars. He remained widely known, in the words of Michael O’Hanlon of the Brookings Institution (praising Broadwell’s biography), as “the finest general of this era and one of the greatest in modern American history.” Unlike George W. Bush and crew who, despite pulling in staggering speaker’s fees and writing memoirs for millions, now found themselves in a far different set of shadows, he looked like the ultimate survivor — until, of course, books and “bedsides” resurfaced in unexpected ways.

In the Iraq surge moment, the liberal advocacy group MoveOn.org unsuccessfully tried to label him “General Betray Us.” Now, as his affair with Broadwell unraveled into the reality TV show of our moment, he became General Betray Himself, a figure of derision, an old man with a young babe, the “cloak-and-shag-her” guy (as one New York Post screaming headline put it).

So here you have it, the two paradigmatic figures of the closing of the “American Century”: the president’s son whose ambitions were stoked by Texas politics after years in the personal wilderness and the man who married the superintendent’s daughter and rose like a meteor in a military that could never win a war. In the end, as the faces of American-disaster-masquerading-as-success, neither made it out of town before shame caught up with them. It’s a measure of their importance, however, that Bush was finally put to flight by a global economic meltdown, Petraeus by the local sexual version of the same. Again, it’s history vs. farce.

Or think of the Petraeus version of collapse as a tryout for the fall of the American empire, writ very small, with Jill Kelley and Paula Broadwell as our Gibbons and the volume of email, including military sexting, taking the place of his six volumes. A poster general for American decline, David Petraeus will be a footnote to history, a man out for himself who simply went a bridge or a book too far. George W. and crew were the real thing: genuine mad visionaries who simply mistook their dreams and fantasies for reality.

But wasn’t it fun while it lasted? Wasn’t it a blast to occupy Washington, be treated as a demi-god, go to Pirate-themed parties in Tampa with a 28-motorcycle police escort, and direct your own biography… even if it did end as Fifty Shades of Khaki?

Tom Engelhardt, co-founder of the American Empire Project and author of The United States of Fear as well as The End of Victory Culture, his history of the Cold War, runs the Nation Institute’s TomDispatch.com. His latest book, co-authored with Nick Turse, is Terminator Planet: The First History of Drone Warfare, 2001-2050. You can see his recent interview with Bill Moyers on supersized politics, drones, and other subjects by clicking here.

[Note for TomDispatch Readers: A small bow to several sites that I always find particularly helpful: my daily companion Antiwar.com, Juan Cole’s invaluable Informed Comment blog, the always provocative War in Context run by Paul Woodward, and Noah Shachtman’sDanger Room at Wired magazine. (At that site, I particularly recommend Spencer Ackerman’s mea culpa for having been drawn into the cult of Petraeus. Scores of other journalists and pundits had far more reason to write such a piece -- and didn’t.) By the way, in case you think that, until recently, it wasn’t possible for anyone to see what is now commonly being written about the general, check out a piece I posted in 2008 under the title “Selling the President’s General.”]

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter @TomDispatch and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch book, Nick Turse’s The Changing Face of Empire: Special Ops, Drones, Proxy Fighters, Secret Bases, and Cyberwarfare.

Copyright 2012 Tom Engelhardt

]]>Paula Broadwell, whose affair with Gen. David Petraeus brought his career to a sudden end last week, had sought to help defend his decision in 2010 to allow village destruction in Afghanistan that not only violated his own previous guidance but the international laws of war.

But her efforts had [...]]]>

Paula Broadwell, whose affair with Gen. David Petraeus brought his career to a sudden end last week, had sought to help defend his decision in 2010 to allow village destruction in Afghanistan that not only violated his own previous guidance but the international laws of war.

Paula Broadwell, whose affair with Gen. David Petraeus brought his career to a sudden end last week, had sought to help defend his decision in 2010 to allow village destruction in Afghanistan that not only violated his own previous guidance but the international laws of war.

But her efforts had the opposite effect.

The new Petraeus policy guidance allowed the destruction of villages in three districts of Kandahar province if the population did not tell U.S. forces where homemade bombs were hidden.

In early January 2010, Broadwell went to visit the Combined Task Force I-320th in Kandahar to write a story justifying the decision to destroy the village of Tarok Kaloche and much of three other villages in its area of operations.

Ironically, it was Broadwell who introduced the complete razing of the village of Tarok Kalache in in Kandahar’s Arghandab Valley in October 2010 to the blogosphere. Dramatic photographs of the village before and after it was razed, which she had obtained from U.S. military sources, were published with her article in the military blog Best Defense Jan. 13, 2011.

The pictures and her article brought a highly critical response from blogger Joshua Foust, who is a specialist on Afghanistan.

Tarok Kalache was only one of many villages destroyed or nearly destroyed in an October 2010 offensive by U.S. forces in three districts of Kandahar Province, because the heavy concentrations of IEDs had made clearing the village by conventional forces too costly.

In the late summer and early fall, commanders in those districts had been ordered to clear the villages of Taliban presence, but they had taken heavy casualties from IEDs planted in and around the villages.

As commander of Combined Task Force I-320th, Lt. Col. David Flynn was responsible for several villages in the Arghandab valley, including Tarok Kalache.

Flynn told Spencer Ackerman of the Danger Room blog in early February 2011 that, once he felt he had the necessary intelligence on IEDs in Tarok Kalache, he had adopted a plan to destroy the village, first with mine clearing charges, which destroyed everything within a swath 100 yards long and wide enough for a tank, then with aerial bombing.

U.S. forces completed the destruction Oct. 6, 2010, dropping 25 2,000-pound bombs on what remained of Tarok Kalache’s 36 compounds and gardens, according to Flynn’s account.

And in an interview with the Daily Mail nearly three weeks after Tarok Kalache had been flattened, Flynn revealed that he had just told residents of Khosrow Sofla that if they didn’t inform him of the location of the IEDs in their village within a few days, he would destroy the village.

Flynn later confirmed to Ackerman that he had told the residents, if they couldn’t tell him exactly where the bombs were located, he would have no way of disposing of them without blowing up the buildings.

The sequence of events clearly suggests that Flynn was using the destruction of Tarok Kalache to convince the residents of Khosrow Sofla that the same thing would happen to them if they didn’t provide the information about IEDs demanded by Flynn.

That tactic apparently succeeded. Carlotta Gall reported in The New York Times Mar. 11, 2011 that after seeing what had happened to Tarok Kalache, the residents of the still undestroyed homes in Khosrow Sofla had hired a former mujahedeen to defuse the IEDs.

In her fawning biography of Petraeus, Broadwell quotes Flynn’s response to being informed by the Khosrow Sofla village chief that the IEDs were all gone, which U.S. troops had verified: “No dozers. No mass punishment. They were already punished by the Taliban.”

The destruction of Tarok Kalache was thus a “collective punishment” of the residents of the village as well as “intimidation” of the residents of Khosrow Sofla – practices that were strictly forbidden by the 1949 Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons.

Article 33 of that agreement states, “Collective penalties and likewise all measures of intimidation or of terrorism are prohibited.”

The village destruction also contravened a central principle of the counterinsurgency guidance that had been promulgated by Gen. Stanley A. McChrystal when he became the top commander in Afghanistan in 2009.

“Destroying a home or property jeopardises the livelihood of an entire family – and creates more insurgents,” said McChrystal’s guidance.

Petraeus had confirmed that prohibition in an August 2010 guidance, warning that killing civilians or damaging their property would “create more enemies than our operations eliminate”.

But Petraeus was under pressure from the Barack Obama administration to produce tangible evidence of “progress” that could be used to justify troop withdrawals. He needed to be able cite the clearing of those villages, regardless of the political fallout.

Petraeus himself clearly approved the general policy allowing the destruction of villages by Flynn and other commanders in Kandahar in late 2010. Flynn told Ackerman he had sent his plan up the chain of command and believed that International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) headquarters were informed.

Carlotta Gall reported Mar. 11, 2011 that revised guidelines “reissued” by Petraeus permitted the total destruction of a village such in Tarok Kalache, according to a NATO official.

Although the large-scale demolition of homes had been reported by the Times in November, it had not generated any significant reaction in the United States. But in Afghanistan, the home destruction created frictions between Afghans and Petraeus’s command over the loss of homes and livelihoods.

When Broadwell traveled to Flynn’s command post in early January 2011, Petraeus was anticipating a story in the New York Times on the growing friction over the home destruction.

Broadwell’s first article for Best Defense was published Jan. 13, 2011, the same day as the New York Times article reporting that the Afghan government estimate of property damage from the destruction of homes and fields was 71 times higher than the 1.4-million-dollar ISAF estimate.

Broadwell was introduced by Ricks as a “friend of the blog” and as “Best Defense Afghanistan Correspondent”.

Although a note following her article referred to her as the author of a forthcoming book on Petraeus, Broadwell was ostensibly writing as an independent journalist rather than as a constant companion of Petraeus.

The article portrayed Flynn as forced to choose between “suffering the tragic losses and the horrific daily amputees” to clear the four villages in question and destroying the IED-laden homes.

In a comment apparently reflecting Petraeus’s concern, she said the unit “could not afford to lose momentum”.

Broadwell claimed the residents had abandoned the village when the Taliban “conducted an intimidation campaign to chase the villagers out”.

After Afghanistan blogger Joshua Foust sharply criticised her lack of concern about the razing of Tarok Kolache, Broadwell wrote on her Facebook page, “I definitely have sympathy for the villagers who had been displaced, even though they made the judgment call to ‘sell’ the village to the Taliban….”

Both those explanations were untrue, however. Former residents told IPS reporter Shah Noori in February that they had begun leaving their homes only in August when the Taliban began gearing up for an assault by U.S. troops by laying IEDs.

They also said the Taliban had allowed residents to return to check on their houses, and to tend their gardens and orchards.

Broadwell repeated an ISAF claim that the compounds were booby-trapped, but residents insisted to Noori that only some compounds had explosives.

Finally Broadwell claimed that the villagers who had lost their homes and gardens had told Petraeus and other visitors that “Flynn was their hero and they wanted him to move into the village with them.”

Then she acknowledged that villagers were “pissed about the loss of their mud huts”, adding cheerfully, “but that’s why the BUILD story is important here.”

*Gareth Porter, an investigative historian and journalist specialising in U.S. national security policy, received the UK-based Gellhorn Prize for journalism for 2011 for articles on the U.S. war in Afghanistan.

]]>Further to Jeremy Scahill’s reporting on General David Petraeus’s impact on the CIA is a post at the Afghanistan Study Group by Mary Kaszynski on the costs and feasiblity of nation-building in the war-torn country:

Bing West, assistant Secretary of Defense for President Reagan, had this to say about [...]]]>

Further to Jeremy Scahill’s reporting on General David Petraeus’s impact on the CIA is a post at the Afghanistan Study Group by Mary Kaszynski on the costs and feasiblity of nation-building in the war-torn country:

Further to Jeremy Scahill’s reporting on General David Petraeus’s impact on the CIA is a post at the Afghanistan Study Group by Mary Kaszynski on the costs and feasiblity of nation-building in the war-torn country:

]]>Bing West, assistant Secretary of Defense for President Reagan, had this to say about Gen. Petraeus and Afghanistan:

“Gen. Petraeus’s concept of nation building as a military mission probably will not endure. Our military can train the armed forces of others (if they are willing) and, in Afghanistan, we can leave behind a cadre to destroy nascent terrorist havens. But American soldiers don’t know how to build Minneapolis or Memphis, let alone Muslim nations.”

West pinpointed one of the fundamental flaws of nation-building. U.S. troops are most capable in the world, but they are trained for combat, not building roads and distributing food aid.

There’s another big problem with nation-building in Afghanistan: it is very expensive. And with the a national debt of over $16 trillion, the U.S. cannot afford to spend billions more on the war in Afghanistan.

War costs ramped up significantly as the U.S. mission in Afghanistan expanded. From 2001 to 2006, spending on the war did not exceed $20 billion per year. In 2010, 2011, and 2012, war costs were over $100 billion per year.

The Nation’s Jeremy Scahill injects some badly needed context into the media frenzy over David Petraeus’s CIA resignation by examining the four-star General’s legacy against the backdrop of an increasingly militarized intelligence agency:

As head of US Central Command in 2009, Petraeus issued execute orders that significantly broadened the ability [...]]]>

The Nation’s Jeremy Scahill injects some badly needed context into the media frenzy over David Petraeus’s CIA resignation by examining the four-star General’s legacy against the backdrop of an increasingly militarized intelligence agency:

The Nation’s Jeremy Scahill injects some badly needed context into the media frenzy over David Petraeus’s CIA resignation by examining the four-star General’s legacy against the backdrop of an increasingly militarized intelligence agency:

]]>As head of US Central Command in 2009, Petraeus issued execute orders that significantly broadened the ability of US forces to operate in a variety of countries, including Yemen, where US forces began conducting missile strikes later that year. During Petraeus’s short tenure at the CIA, drone strikes conducted by the agency, sometimes in conjunction with JSOC, escalated dramatically in Yemen; in his first month in office, he oversaw a series of strikes that killed three US citizens, including 16-year-old Abdulrahman Awlaki. In some cases, such as the raid that killed Osama bin Laden in Pakistan, commandos from the elite JSOC operated under the auspices of the CIA, so that the mission could be kept secret if it went wrong.