Professor Walt was a Resident Associate of the Carnegie Endowment for Peace and a Guest Scholar at the Brookings Institution, and he has also served as a consultant for the Institute of Defense Analyses, the Center for Naval Analyses, and the National Defense University. He presently serves on the editorial boards of Foreign Policy, Security Studies, International Relations, and the Journal of Cold War Studies.

via IPS News

Responding to growing criticism by human rights groups and foreign governments, U.S. President Barack Obama Thursday announced potentially significant shifts in what his predecessor called the “global war on terror”.

In a major policy address at the National Defense University here, Obama said drone strikes against [...]]]>

via IPS News

Responding to growing criticism by human rights groups and foreign governments, U.S. President Barack Obama Thursday announced potentially significant shifts in what his predecessor called the “global war on terror”.

In a major policy address at the National Defense University here, Obama said drone strikes against terrorist suspects abroad will be carried out under substantially more limited conditions than during his first term in office.

He also renewed his drive to close the U.S. detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, which currently only holds 166 prisoners.

In particular, he announced the lifting of a three-year-old moratorium on repatriating Yemeni detainees to their homeland and the appointment in the near future of senior officials at both the State Department and the Pentagon to expedite the transfer the 30 other prisoners who have been cleared for release to third countries.

In addition, he said he will press Congress to amend and ultimately repeal its 2001 Authorization to Use Military Force (AUMF) against Al-Qaeda and others deemed responsible for the 9/11 attacks “(in order) to determine how we can continue to fight terrorists without keeping America on a perpetual war-time footing.”

The AUMF created the legal basis for most of the actions – and alleged excesses — by U.S. military and intelligence agencies against alleged terrorists and their supporters since 9/11.

“The AUMF is now nearly 12 years old. The Afghan War is coming to an end. Core Al-Qaeda is a shell of its former self,” he declared. “Groups like AQAP (Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula) must be dealt with, but in the years to come, not every collection of thugs that labels themselves Al-Qaeda will pose a credible threat to the United States.”

“Unless we discipline our thinking and our actions, we may be drawn into more wars we don’t need to fight, or continue to grant presidents unbound powers more suited for traditional armed conflicts between nation states,” he warned.

His remarks gained a cautious – if somewhat sceptical and impatient – welcome from some of the groups that have harshly criticised Obama’s for his failure to make a more decisive break with some of former President George W. Bush’s policies and to close Guantanamo, and his heavy first-term reliance on drone strikes against Al-Qaeda and other terrorist suspects.

“President Obama is right to say that we cannot be on a war footing forever – but the time to take our country off the global warpath and fully restore the rule of law is now, not at some indeterminate future point,” said Anthony Romero, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

Romero especially praised Obama’s initial moves to transfer detainees at Guantanamo but noted that he had failed to offer a plan to deal with those prisoners who are considered too dangerous to release but who cannot be tried in U.S. courts for lack of admissible evidence. He also called the new curbs on drone strikes “promising” but criticised Obama’s continued defence of targeted killings.

Obama’s speech came amidst growing controversy over his use of drone strikes in countries – particularly Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia – with which the U.S. is not at war. Since 9/11, the U.S. has conducted more than 400 strikes in the three countries with a total death toll estimated to range between 3,300 and nearly 5,000, depending on the source. The vast majority of these strikes were carried out during Obama’s first term.

While top administration officials have claimed that almost all of the victims were suspected high-level terrorists, human rights groups, as well as local sources, have insisted that many civilian non-combatants – as well as low-level members of militant groups — have also been killed.

In a letter sent to Obama last month, some of the country’s leading human rights groups, including the ACLU, Amnesty International, and Human Rights First, questioned the legality of the criteria used by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the Pentagon’s Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) to select targets.

Earlier this month, the legal adviser to former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Harold Koh, also criticised the administration for the lack of transparency and discipline surrounding the drone programme.

In his speech Thursday, Obama acknowledged the “wide gap” between his government and independent assessments of casualties, but he strongly defended the programme as effective, particularly in crippling Al-Qaeda’s Pakistan-based leadership, legal under the AUMF, and more humane than the alternative in that “(c)onventional airpower or missiles are far less precise than drones, and likely to cause more civilian casualties and local outrage.”

“To do nothing in the face of terrorist networks would invite far more civilian casualties – not just in our cities at home and facilities abroad, but also in the very places – like Sana’a and Kabul and Mogadishu – where terrorists seek a foothold,” he said.

According to a “Fact Sheet” released by the White House, lethal force can be used outside of areas of active hostilities when there is a “near certainty that a terrorist target who poses a continuing, imminent threat to U.S. persons” is present and that non-combatants will not be injured or killed. In addition, U.S. officials must determine that capture is not feasible and that local authorities cannot or will not effectively address the threat.

The fact sheet appeared to signal an end to so-called “signature strikes” that have been used against groups of men whose precise is identity is unknown but who, based on surveillance, are believed to be members of Al-Qaeda or affiliated groups.

If the target is a U.S. citizen, such as Anwar Awlaki, a U.S.-born cleric who the administration alleged had become an operational leader of AQAP and was killed in a 2011 drone strike in Yemen, Obama said there would be an additional layer of review and that he would engage Congress on the possibility of establishing a secret court or an independent oversight board in the executive branch.

On Wednesday, the Justice Department disclosed that three other U.S. citizens – none of whom were specifically targeted – have been killed in drone strikes outside Afghanistan.

On Guantanamo, where 102 of the 166 remaining detainees are participating in a three-month-old hunger strike, Obama said he would permit the 56 Yemenis there whose have been cleared for release to return home “on a case-by-case basis”. He also re-affirmed his determination to transfer all remaining detainees to super-max or military prisons on U.S. territory – a move that Congress has so far strongly resisted. He also said he would insist that every detainee have access to the courts to review their case.

In addition to addressing the festering drone issue and Guantanamo, however, the main thrust of Thursday’s speech appeared designed to mark what Obama called a “crossroads” in the struggle against Al-Qaeda and its affiliates and how the threat from them has changed.

“Lethal yet less capable Al-Qaeda affiliates. Threats to diplomatic facilities and businesses abroad. Homegrown extremists. This is the future of terrorism,” he said. “We must take these threats seriously, and do all we can to confront them. But as we shape our response, we have to recognise that the scale of this threat closely resembles the types of attacks we faced before 9/11.”

“Beyond Afghanistan,” he said later, “we must define our effort not as a boundless ‘global war on terror’ – but rather as a series of persistent, targeted efforts to dismantle specific networks of violent extremists that threaten America.”

Obama also disclosed he had signed a Presidential Policy Guidance Wednesday to codify the more restrictive guidelines governing the use of force.

White House officials who brief reporters before the speech suggested that, among other provisions, the Guidance called for gradually shifting responsibility for drone strikes and targeted killings from the CIA to the Pentagon – a reform long sought by human-rights groups.

]]>by Mattea Kramer and Chris Hellman

via Tom Dispatch

Imagine a labyrinthine government department so bloated that few have any clear idea of just what its countless pieces do. Imagine that tens of billions of tax dollars are disappearing into it annually, black hole-style, since it can’t pass a [...]]]>

by Mattea Kramer and Chris Hellman

via Tom Dispatch

Imagine a labyrinthine government department so bloated that few have any clear idea of just what its countless pieces do. Imagine that tens of billions of tax dollars are disappearing into it annually, black hole-style, since it can’t pass a congressionally mandated audit.

Now, imagine that there are two such departments, both gigantic, and you’re beginning to grasp the new, twenty-first century American security paradigm.

For decades, the Department of Defense has met this definition to a T. Since 2003, however, it hasn’t been alone. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which celebrates its 10th birthday this March, has grown into a miniature Pentagon. It’s supposed to be the actual “defense” department — since the Pentagon is essentially a Department of Offense — and it’s rife with all the same issues and defects that critics of the military-industrial complex have decried for decades. In other words, “homeland security” has become another obese boondoggle.

But here’s the strange thing: unlike the Pentagon, this monstrosity draws no attention whatsoever — even though, by our calculations, this country has spent a jaw-dropping $791 billion on “homeland security” since 9/11. To give you a sense of just how big that is, Washington spent an inflation-adjusted $500 billion on the entire New Deal.

Despite sucking up a sum of money that could have rebuilt crumbling infrastructure from coast to coast, this new agency and the very concept of “homeland security” have largely flown beneath the media radar — with disastrous results.

And that’s really no surprise, given how the DHS came into existence.

A few months before 9/11, Congress issued a national security reportacknowledging that U.S. defense policy had not evolved to meet the challenges of the twenty-first century. The report recommended a “national homeland security agency” with a single leader to oversee homeland security-style initiatives across the full range of the federal government. Although the report warned that a terrorist attack could take place on American soil, it collected dust.

Then the attack came, and lawmakers of both political parties and the American public wanted swift, decisive action. President George W. Bush’s top officials and advisers saw in 9/11 their main chance to knock off Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein and establish a Pax Americana in the Greater Middle East. Others, who generally called themselves champions of small government, saw an opportunity to expand big government at home by increasing security spending.

Their decision to combine domestic security under one agency turned out to be like sending the Titanic into the nearest field of icebergs.

President Bush first created an Office of Homeland Security in the White House and then, with the Homeland Security Act of 2002, laid plans for a new executive department. The DHS was funded with billions of dollars and staffed with 180,000 federal employees when it opened for business on March 1, 2003. It qualified as the largest reorganization of the federal government since 1947 when, fittingly, the Department of Defense was established.

Announcing plans for this new branch of government, President Bush made a little-known declaration of “mission accomplished” that long preceded thatinfamous banner strung up on an aircraft carrier to celebrate his “victory” in Iraq. In November 2002, he said, “The continuing threat of terrorism, the threat of mass murder on our own soil, will be met with a unified, effective response.”

Mission unaccomplished (big time).

A decade later, a close look at the hodge-podge of homeland security programs that now spans the U.S. government reveals that there’s nothing “unified” about it. Not all homeland security programs are managed through the Department of Homeland Security, nor are all programs at the Department of Homeland Security related to securing the homeland.

A decade later, a close look at the hodge-podge of homeland security programs that now spans the U.S. government reveals that there’s nothing “unified” about it. Not all homeland security programs are managed through the Department of Homeland Security, nor are all programs at the Department of Homeland Security related to securing the homeland.

Federal officials created the DHS by pulling together 22 existing government departments, including stand-alone agencies like the Federal Emergency Management Agency, better known by its acronym FEMA, and the Coast Guard, which came with programs both related and unrelated to counterterrorism. They also brought into the DHS a host of programs that had previously existed as parts of other agencies like the Nuclear Incident Response Team from the Department of Energy and the Transportation Security Administration at the Department of Transportation. To knit these disparate parts together, officials built a mammoth bureaucracy over an already existing set of bureaucracies. At the same time, they left a host of counterterrorism programs scattered across the rest of the federal government, which means, a decade later, many activities at the DHS are duplicated by similar programs elsewhere.

A trail of breadcrumbs in federal budget documents shows how much is spent on homeland security and by which agencies, though details about what that money is buying are scarce. The DHS budget was $60 billion last year. However, only $35 billion was designated for counterterrorism programs of various sorts. In the meantime, total federal funding for (small-h, small-s) homeland security was $68 billion — a number that, in addition to the DHS money, includes $17 billion for the Department of Defense, plus around $4 billion each for the Departments of Justice and Health and Human Services, with the last few billion scattered across virtually every other federal agency in existence.

From the time this new security bureaucracy rumbled into operation, the Government Accountability Office (GAO), Washington’s internal watchdog, called the DHS a “high risk” proposition. And it’s never changed its tune. Regular GAO reports scrutinize the department and identify major problems. In March of last year, for instance, one GAO report noted that the office had recommended a total of 1,600 changes. At that time, the department had only “addressed about half of them” — and addressed doesn’t necessarily mean solved.

So rest assured, in the best of all possible homeland security worlds, there are only 800-odd issues outstanding, according to the government’s own watchdog, after we as a nation poured $791 billion down the homeland security rabbit hole. Indeed, there remain gaping problems in the very areas that the DHS is supposedly securing on our behalf:

* Consider port security: you wouldn’t have much trouble overnighting a weapon of mass destruction into the United States. Cargo terminals are the entry point for containers from all over the world, and a series of reports have found myriad vulnerabilities — including gaps in screening for nuclear and radiological materials. After spending $200 million on new screening technology, the DHS determined it wouldn’t deliver sufficient improvements and cancelled the program (but not the cost to you, the taxpayer).

* Then there are the problems of screening people crossing into this country. The lion’s share of responsibility for border security lies with part of the DHS, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), which had an $11.7 billion budget in fiscal 2012. But in the land of utter duplication that is Washington’s version of counterterrorism, there is also something called the Border Security Program at the State Department, with a separate pot of funding to the tune of $2.2 billion last year. The jury’s out on whether these programs are faintly doing their jobs, even as they themselves define them. As with so many other DHS programs, the one thing they are doing successfully is closing andlocking down what was once considered an “open” society.

* For around $14 billion each year, the Department of Homeland Security handles disaster response and recovery through FEMA, something that’s meant to encompass preparedness for man-made as well as natural disasters. But a 2012 investigation by the GAO found that FEMA employs an outdated method of assessing a disaster-struck region’s ability to respond and recover without federal intervention — helpfully, that report came out just a month before Hurricane Sandy.

* Recently, it came to light that the DHS had spent $431 million on a radio system for communication within the department — but only one of more than 400 employees questioned about the system claimed to have the slightest idea how to use it. It’s never surprising to hear that officials at separate agencies have trouble coordinating, but this was an indication that, even within the DHS, employees struggle with the basics of communication.

* In a survey that covered all federal departments, DHS employees reported rock-bottom levels of engagement with their work. Its own workers called the DHS the worst federal agency to work for.

Those are just a few of a multitude of glaring problems inside the now decade-old department. Because homeland security is not confined to one agency, however, rest assured that neither is its bungling:

* There is, for instance, that $17 billion in homeland security funding at the Department of Defense — a mountain of cash for defending against terrorist attacks, protecting U.S. airspace, and providing security at military bases. But perhaps defense officials feel that $17 billion is insufficient, since an October 2012 report by the GAO found the Pentagon had outdated and incomplete plans for responding to a domestic attack, including confusion about the chain of command should such an event take place. That should be no surprise, though: the Pentagon is so replete with oversight problems and obsolete, astronomically expensive programs that it makes the DHS look like a trim, well-oiled machine.

* Or consider the domestic counterterrorism unit at the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF), which enjoyed $461 million in homeland security funding last year and is housed not at the DHS or the Pentagon but at the Department of Justice. ATF made headlines for giving marked firearms to Mexican smugglers and losing track of them — and then finding that the weapons were used in heinous crimes. More recently, in the wake of the Newtown massacre, ATF has drawn attention because it fails one of the most obvious tests of oversight and responsibility: it lacks a confirmed director at the helm of its operations. (According to The Hill newspaper, Sen. Charles Grassley (R-IA) is currently holding up President Obama’s appointment to head the agency.)

Washington has poured staggering billions into securing the so-called homeland, but in so many of the areas meant to be secured there remain glaring holes the size of that gaping wound in the Titanic’s side. And yet over the past decade — even with these problems — terrorist attacks on the homeland have scarcely hurt a soul. That may offer a clue into just how misplaced the very notion of the Department of Homeland Security was in the first place. In the wake of 9/11, pouring tiny percentages of that DHS money into less flashy safety issues, from death by food to death by gun to death by car, to mention just three, might have made Americans genuinely safer at, by comparison, minimal cost.

Perhaps the strangest part of homeland security operations may be this: there isno agreed-upon definition for just what homeland security is. The funds Washington has poured into the concept will soon enough approach a trillion dollars and yet it’s a concept with no clear boundaries that no one can agree on. Worse yet, few are asking the hard questions about what security we actually need or how best to achieve it. Instead, Washington has built a sprawling bureaucracy riddled with problems and set it on autopilot.

And that brings us to today. Budget cuts are in the pipeline for most federal programs, but many lawmakers vocally oppose any reductions in security funding. What’s painfully clear is this: the mere fact that a program is given the label of national or homeland security does not mean that its downsizing would compromise American safety. Overwhelming evidence of waste, duplication, and poor management suggests that Washington could spend far less on security, target it better, and be so much safer.

Meanwhile, the same report that warned in early 2001 of a terrorist attack on U.S. soil also recommended redoubling funding for education in science and technology.

In the current budget-cutting fever, the urge to protect boundless funding for national security programs by dismantling investment essential to this country’s greatness — including world-class education and infrastructure systems — is bound to be powerful. So whenever you hear the phrase “homeland security,” watch out: your long-term safety may be at risk.

Mattea Kramer is research director at National Priorities Project, where Chris Hellman is senior research analyst. Both are TomDispatch regulars. They co-authored the book A People’s Guide to the Federal Budget.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch book, Nick Turse’s The Changing Face of Empire: Special Ops, Drones, Proxy Fighters, Secret Bases, and Cyberwarfare.

Copyright 2013 Mattea Kramer and Chris Hellman

]]>via IPS News

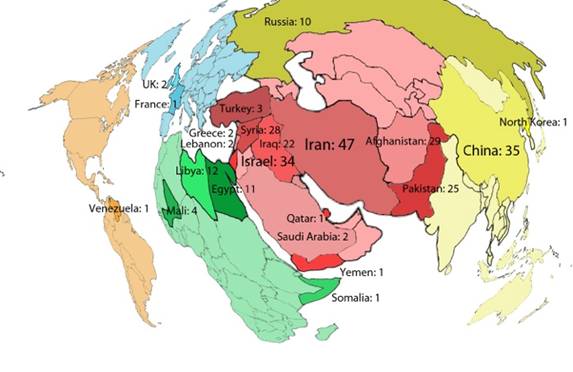

Graphic: The figures signify the number of times each country was mentioned in the Oct. 22 presidential debate. Credit: Zachary Fleischmann/IPS

U.S. strategy in the Greater Middle East, which has dominated foreign policy-making since the 9/11 attacks more than 11 years ago, similarly dominated the third and last debate between [...]]]>

via IPS News

Graphic: The figures signify the number of times each country was mentioned in the Oct. 22 presidential debate. Credit: Zachary Fleischmann/IPS

U.S. strategy in the Greater Middle East, which has dominated foreign policy-making since the 9/11 attacks more than 11 years ago, similarly dominated the third and last debate between President Barack Obama and Governor Mitt Romney Monday night.

The biggest surprise of the debate, which was supposed to be devoted exclusively to foreign policy and national security, was how much Romney agreed with Obama’s approach to the region.

His apparent embrace of the president’s policies appeared consistent with his recent efforts to reassure centrist voters that he is not as far right in his views as his primary campaign or his choice for vice president, Rep. Joe Ryan, would suggest.

The focus on the Greater Middle East, which took up roughly two-thirds of the 90-minute debate, reflected a number of factors in addition to the perception that the region is the main source of threats to U.S. security, a notion that Romney tried hard to foster during the debate.

“It’s partly because all candidates have to pander to Israel’s supporters here in the United States, but also four decades of misconduct have made the U.S. deeply unpopular in much of the Arab and Islamic world,” Stephen Walt, a Harvard international relations professor who blogs on foreignpolicy.com, told IPS.

“Add to that the mess Obama inherited from (George W.) Bush, and you can see why both candidates had to keep talking about the region,” he said.

But the region’s domination in the debate also came largely at the expense of other key regions, countries and global issues – testimony to the degree to which Bush’s legacy, particularly from his first term when neo-conservatives and other hawks ruled the foreign-policy roost, continues to define Washington’s relationship to the world.

Of all the countries cited by the moderator and the two candidates, China was the only one outside the Middle East that evoked any substantial discussion, albeit limited to trade and currency issues.

Romney re-iterated his pledge to label Beijing a “currency manipulator” on his first day in office, while Obama for the first time described Beijing as an “adversary” as well as a “partner” – a reflection of how China-bashing has become a predictable feature of presidential races since the end of the Cold War.

With the exception of one very short reference (by Romney) to Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez and another to trade with Latin America, Washington’s southern neighbours were completely ignored by the two candidates, as was Canada and all of sub-Saharan Africa, except Somalia and Mali where Romney charged that “al Qaeda-type individuals” had taken over the northern part of the country.

Not even the long-running financial crisis in the European Union (EU) – arguably, one of the greatest threats to U.S. national security and economic recovery – came up, although Romney warned several times that the U.S. could become “Greece” if it fails to tackle its debt problems.

Similarly, the big emerging democracies, including India, Brazil, South Africa, and Indonesia – all of which have been wooed by the Obama administration – went entirely unmentioned, although at least one commentator, Tanvi Madan, head of the Indian Project at the Brookings Institution, said Indians should “breathe a sigh of relief” over its omission since it signaled a lack of controversy over Washington’s relations with New Delhi.

Another key emerging democracy, Turkey, was mentioned several times, but only in relation to the civil war in Syria.

And climate change or global warming, which has been considered a national-security threat by U.S. intelligence agencies and the Pentagon for almost a decade, was a no-show at the debate.

“There was no serious discussion of climate change, the Euro crisis, the failed drug war, or the long-term strategic consequences of drone wars, cyberwar, and an increasingly ineffective set of global institutions,” noted Walt.

“Neither candidate offered a convincing diagnosis of the challenges we face in a globalised world, or the best way for the U.S. to advance its interests and values in a world it no longer dominates.”

Romney, whose top foreign-policy advisers include key neo-conservatives who were major promoters of Bush’s misadventures in the region, spent much of the debate repeatedly assuring the audience that he would be the un-Bush when it came to foreign policy.

“We don’t want another Iraq,” he said at one point in an apparent endorsement of Obama’s drone strategy. “We don’t want another Afghanistan. That’s not the right course for us.”

“I want to see peace,” he asserted somewhat awkwardly as he began his summation, suggesting that it was a talking point his coaches told him he must impress upon his audience before he left the hall in Boca Raton, Florida.

“Romney clearly decided he needed to head off perceptions of himself as a throwback to George W. Bush-era foreign policy adventurism, repeatedly stressing his desire for a peaceful world,” wrote Greg Sargent, a Washington Post blogger.

So strongly did he affirm most of Obama’s policies that, for those who hadn’t been paying close attention to Romney’s previous stands, the president’s charge that his rival’s foreign policy was “wrong and reckless” must have sounded somewhat puzzling.

As Obama was forced to remind the audience repeatedly, Romney’s positions on these issues have been “all over the map” since he launched his candidacy more than two years ago.

“I found it confusing, because he has spent much of the campaign season in some ways recycling Bush’s foreign policy, and, at least for one night, he seemed to throw the neo-cons under the bus,” said Charles Kupchan, a foreign policy specialist at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“Whether it was accepting the withdrawal timetable in Afghanistan, walking back a more aggressive stance on Syria, or basically agreeing with Obama’s approach on Iran, he seems to be stepping away from a lot of the positions he was taking just a few weeks ago,” he noted. “At this point, it’s impossible for voters to actually know what he thinks because he spent most of the campaign embracing a platform that was much further to the right.”

That Obama, who took the offensive from the outset and retained it for the next 90 minutes, won the debate was conceded by virtually all but the most partisan Republican commentators, with some analysts calling the president’s performance as decisive a victory as that which Romney achieved in the first debate earlier this month and which reversed his then-fading fortunes.

A CBS/Knowledge Networks poll of undecided voters taken immediately after the debate found that 53 percent of respondents thought Obama had won; only 23 percent saw Romney as the victor.

Whether that will be sufficient to reverse Romney’s recent gains in the polls – national surveys currently show a virtual tie among likely voters – remains to be seen.

Foreign policy remains a relatively minor issue in the minds of the vast majority of voters concerned mostly about the economy and jobs – one reason why, at every opportunity, Romney Monday tried, with some success, to steer the debate back toward those problems.

]]>Posted by Tom Dispatch

As he campaigns for reelection, President Obama periodically reminds audiences of his success in terminating the deeply unpopular Iraq War. With fingers crossed for luck, he vows to do the same with the equally unpopular [...]]]>

Posted by Tom Dispatch

As he campaigns for reelection, President Obama periodically reminds audiences of his success in terminating the deeply unpopular Iraq War. With fingers crossed for luck, he vows to do the same with the equally unpopular war in Afghanistan. If not exactly a peacemaker, our Nobel Peace Prize-winning president can (with some justification) at least claim credit for being a war-ender.

Yet when it comes to military policy, the Obama administration’s success in shutting down wars conducted in plain sight tells only half the story, and the lesser half at that. More significant has been this president’s enthusiasm for instigating or expanding secret wars, those conducted out of sight and by commandos.

President Franklin Roosevelt may not have invented the airplane, but during World War II he transformed strategic bombing into one of the principal emblems of the reigning American way of war. General Dwight D. Eisenhower had nothing to do with the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb. Yet, as president, Ike’s strategy of Massive Retaliation made nukes the centerpiece of U.S. national security policy.

So, too, with Barack Obama and special operations forces. The U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) with its constituent operating forces — Green Berets, Army Rangers, Navy SEALs, and the like — predated his presidency by decades. Yet it is only on Obama’s watch that these secret warriors have reached the pinnacle of the U.S. military’s prestige hierarchy.

John F. Kennedy famously gave the Green Berets their distinctive headgear. Obama has endowed the whole special operations “community” with something less decorative but far more important: privileged status that provides special operators with maximum autonomy while insulating them from the vagaries of politics, budgetary or otherwise. Congress may yet require the Pentagon to undertake some (very modest) belt-tightening, but one thing’s for sure: no one is going to tell USSOCOM to go on a diet. What the special ops types want, they will get, with few questions asked — and virtually none of those few posed in public.

Since 9/11, USSOCOM’s budget hasquadrupled. The special operations order of battle has expanded accordingly. At present, there are an estimated 66,000 uniformed and civilian personnel on the rolls, a doubling in size since 2001 with further growth projected. Yet this expansion had already begun under Obama’s predecessor. His essential contribution has been to broaden the special ops mandate. As one observer put it, the Obama White House let Special Operations Command “off the leash.”

Since 9/11, USSOCOM’s budget hasquadrupled. The special operations order of battle has expanded accordingly. At present, there are an estimated 66,000 uniformed and civilian personnel on the rolls, a doubling in size since 2001 with further growth projected. Yet this expansion had already begun under Obama’s predecessor. His essential contribution has been to broaden the special ops mandate. As one observer put it, the Obama White House let Special Operations Command “off the leash.”

As a consequence, USSOCOM assets today go more places and undertake more missions while enjoying greater freedom of action than ever before. After a decade in which Iraq and Afghanistan absorbed the lion’s share of the attention, hitherto neglected swaths of Africa, Asia, and Latin America are receiving greater scrutiny. Already operating in dozens of countries around the world – as many as 120 by the end of this year — special operators engage in activities that range from reconnaissance and counterterrorism to humanitarian assistance and “direct action.” The traditional motto of the Army special forces is “De Oppresso Liber” (“To Free the Oppressed”). A more apt slogan for special operations forces as a whole might be “Coming soon to a Third World country near you!”

The displacement of conventional forces by special operations forces as the preferred U.S. military instrument — the “force of choice” according to the head of USSOCOM, Admiral William McRaven — marks the completion of a decades-long cultural repositioning of the American soldier. The G.I., once represented by the likes of cartoonist Bill Mauldin’s iconic Willie and Joe, is no more, his place taken by today’s elite warrior professional. Mauldin’s creations were heroes, but not superheroes. The nameless, lionized SEALs who killed Osama bin Laden are flesh-and blood Avengers. Willie and Joe were “us.” SEALs are anything but “us.” They occupy a pedestal well above mere mortals. Couch potato America stands in awe of their skill and bravery.

This cultural transformation has important political implications. It represents the ultimate manifestation of the abyss now separating the military and society. Nominally bemoaned by some, including former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and former Joint Chiefs Chairman Admiral Mike Mullen, this civilian-military gap has only grown over the course of decades and is now widely accepted as the norm. As one consequence, the American people have forfeited owner’s rights over their army, having less control over the employment of U.S. forces than New Yorkers have over the management of the Knicks or Yankees.

As admiring spectators, we may take at face value the testimony of experts (even if such testimony is seldom disinterested) who assure us that the SEALs, Rangers, Green Berets, etc. are the best of the best, and that they stand ready to deploy at a moment’s notice so that Americans can sleep soundly in their beds. If the United States is indeed engaged, as Admiral McRaven has said, in “a generational struggle,” we will surely want these guys in our corner.

Even so, allowing war in the shadows to become the new American way of war is not without a downside. Here are three reasons why we should think twice before turning global security over to Admiral McRaven and his associates.

Goodbye accountability. Autonomy and accountability exist in inverse proportion to one another. Indulge the former and kiss the latter goodbye. In practice, the only thing the public knows about special ops activities is what the national security apparatus chooses to reveal. Can you rely on those who speak for that apparatus in Washington to tell the truth? No more than you can rely on JPMorgan Chase to manage your money prudently. Granted, out there in the field, most troops will do the right thing most of the time. On occasion, however, even members of an elite force will stray off the straight-and-narrow. (Until just a few weeks ago, most Americans considered White House Secret Service agents part of an elite force.) Americans have a strong inclination to trust the military. Yet as a famous Republican once said: trust but verify. There’s no verifying things that remain secret. Unleashing USSOCOM is a recipe for mischief.

Hello imperial presidency. From a president’s point of view, one of the appealing things about special forces is that he can send them wherever he wants to do whatever he directs. There’s no need to ask permission or to explain. Employing USSOCOM as your own private military means never having to say you’re sorry. When President Clinton intervened in Bosnia or Kosovo, when President Bush invaded Afghanistan and Iraq, they at least went on television to clue the rest of us in. However perfunctory the consultations may have been, the White House at least talked things over with the leaders on Capitol Hill. Once in a while, members of Congress even cast votes to indicate approval or disapproval of some military action. With special ops, no such notification or consultation is necessary. The president and his minions have a free hand. Building on the precedents set by Obama, stupid and reckless presidents will enjoy this prerogative no less than shrewd and well-intentioned ones.

And then what…? As U.S. special ops forces roam the world slaying evildoers, the famous question posed by David Petraeus as the invasion of Iraq began — “Tell me how this ends” — rises to the level of Talmudic conundrum. There are certainly plenty of evildoers who wish us ill (primarily but not necessarily in the Greater Middle East). How many will USSOCOM have to liquidate before the job is done? Answering that question becomes all the more difficult given that some of the killing has the effect of adding new recruits to the ranks of the non-well-wishers.

In short, handing war to the special operators severs an already too tenuous link between war and politics; it becomes war for its own sake. Remember George W. Bush’s “Global War on Terror”? Actually, his war was never truly global. War waged in a special-operations-first world just might become truly global — and never-ending. In that case, Admiral McRaven’s “generational struggle” is likely to become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Andrew J. Bacevich is professor of history and international relations at Boston University and a TomDispatch regular. He is editor of the new bookThe Short American Century, just published by Harvard University Press. To listen to Timothy MacBain’s latest Tomcast audio interview in which Bacevich discusses what we don’t know about special operations forces, click here or download it to your iPod here.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter @TomDispatch and join us on Facebook.

Copyright 2012 Andrew J. Bacevich

]]>Stephen M. Walt, co-author of the ground-breaking The Israel Lobby and US Foreign Policy, gave a keynote address on “Obama’s Foreign Policy and the End of the American Era” at an event is co-hosted by the IIEA and UCD’s Clinton Institute for American Studies. You can download the Post [...]]]>

Stephen M. Walt, co-author of the ground-breaking The Israel Lobby and US Foreign Policy, gave a keynote address on “Obama’s Foreign Policy and the End of the American Era” at an event is co-hosted by the IIEA and UCD’s Clinton Institute for American Studies. You can download the Post Event Notes from this event here. Walt’s bio can be found after the fold.

]]>Stephen M. Walt is the Robert and Rene Belfer Professor of International Relations at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. He previously taught at Princeton University and the University of Chicago.

Professor Walt is the author of The Origins of Alliances (1987), Revolution and War (1996), Taming American Power: The Global Response to U.S. Primacy (2005), and, with co-author J.J. Mearsheimer, The Israel Lobby (2007). He writes regularly online at walt.foreignpolicy.com.