by Jasmin Ramsey

The only certainty now about the talks between world powers and Iran over its nuclear program is that the negotiators have their work cut out for them. Other than occasional runaway comments to the press from France, and now China, the parties have remained tight-lipped about their [...]]]>

by Jasmin Ramsey

The only certainty now about the talks between world powers and Iran over its nuclear program is that the negotiators have their work cut out for them. Other than occasional runaway comments to the press from France, and now China, the parties have remained tight-lipped about their closed-door dealings. However, judging by the tone of the briefings by the US and Iran coming out of the 5-day session that ended in Vienna last Friday, the pressure has increased as the self-imposed deadline looms. The negotiations can certainly be extended, but as a senior US official noted in a background briefing to the press:

We are all focused on reaching July 20th. As I’ve said before, if we get close and we need a few more days, I don’t think anyone will mind. But we are very focused on getting it done now. We have all agreed that time is not in anyone’s interest; it won’t help get there. And if indeed by the time we get to July 20th we are still very far apart, then I think we will all have to evaluate what that means and what is possible or not.

What are the odds of the now formally titled “Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action” being signed by Iran and the P5+1 (US, UK, France, China, and Russia plus Germany) at the end of July? Independent scholar and LobeLog contributor Farideh Farhi offered her take during a June 21 interview with Iran Review:

Two factors work in favor of the eventual resolution of the nuclear dossier and transformation of US-Iran relations from a constant state of hostility and non-communication to interaction, even if not necessarily in constructive ways at all times. One is the seriousness of the negotiations and the political will on the part of the current administrations in both countries to prevent the nuclear dossier from becoming a pretext for war or spiraling into something uncontrollable. And the second is the high cost of failure now that both sides have invested so heavily in the talks.

But there are also factors that inhibit confidence in assuming a point of no return to status quo ante. First, in both countries there are political forces that oppose any type of interaction and lessening of tensions, although at this point my take is that opponents, encouraged by regional players, have more significant institutional power in the United States than Iran. In other words, along with political power, they have extensive policy instruments – the most important of which are legally embedded in the sanctions regime – that can be relied upon to undermine or prevent political accord between the two countries.

The second factor is the unequal power relationship between the two countries, which has consistently led various US administrations to be tempted by the argument that economic, political muscle, and military threats will eventually pay off and force various administrations in Iran to give in irrespective of domestic political equations and the stances they have taken within their own political environment. Currently, this second factor is part and parcel of broader indecision or uncertainty in the US’ strategic calculus regarding whether to come to terms with Iran as a prominent regional player or continue its three decade policy of containing it and alternatively Iran’s commitment to being an independent and powerful regional actor irrespective of fears in the neighborhood.

This dynamic of one side always wanting more than the other can give and/or alternatively being unwilling or incapable of matching concessions with what the other side deems as comparable concessions has been the source of impasse in negotiations. This is not to suggest that inflexibility or lack of realism only comes from one side. During the previous administration, Iran also miscalculated in its assessment of the leverage the United States could build through its ferocious sanctions regime in the same way the United States miscalculated in its assessment of the extent to which Iran could expand its nuclear program in the face of sanctions. As such, Iran’s expectation for the sanctions regime that took years to build to be lifted quickly and permanently is as unrealistic as the US expectation for Iran’s enrichment program to be significantly scaled back.

As to the impact of Iran-US direct talks, it is still possible for the unprecedented high profile direct engagement between the two countries in and of itself to lead to some sort of transformation in the relationship irrespective of the results of nuclear talks. If indeed the two countries’ foreign ministers or even presidents can continue to pick up the phone and talk to each other over matters of common concern or for the sake of de-escalating tensions, that by itself is an important achievement of nuclear talks and its significance should not be under-estimated. But this also depends on how the potential failure of nuclear talks is managed by both sides.

Read more here.

This article was first published by LobeLog and was reprinted here with permission. Follow LobeLog on Twitter and like us on Facebook.

Photo: The Iranian nuclear negotiating team headed by Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif (center) and Deputy Foreign Ministers Abbas Araghchi (to Zarif’s right) and Majid Takht-Ravanchi.

]]>by Farideh Farhi

On April 3 the European Parliament (EP) passed a resolution on EU Strategy towards Iran. It proposes the opening of a EU delegation in Tehran; cooperation in a number of areas such as the fight against narcotic drugs, environmental protection, and exchanges of students and academics; engaging [...]]]>

by Farideh Farhi

On April 3 the European Parliament (EP) passed a resolution on EU Strategy towards Iran. It proposes the opening of a EU delegation in Tehran; cooperation in a number of areas such as the fight against narcotic drugs, environmental protection, and exchanges of students and academics; engaging with Iran on ending the Syrian civil war; stabilising Afghanistan; and outlining the prospect of lifting nuclear-related sanctions against Iran once there is a final agreement on the nuclear issue.

The resolution was offered as a signal of the EP’s desire to embark on a new relationship with Iran, but its questioning of the legitimacy of Iran’s 2013 presidential election and recommendation for parliamentary delegations that visit Iran to meet with dissidents angered Tehran and led to the cancellation of a visit by an Iranian parliamentary delegation to Strasbourg in eastern France. Even Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif was compelled to question the powers of the EP, saying it does not have the political and ethical standing to “preach to others.”

I contacted Eldar Mamedov to learn about the politics of this resolution and how it came to be after a couple of visits to Iran by the European Parliament’s delegation. Mamedov is the Political Advisor for the Social-Democratic Group in the Foreign Affairs Committee of the European Parliament. I saw him in Tehran last October when he accompanied a delegation from the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats — this was the first European parliamentary delegation to visit Iran since 2007. He later accompanied the delegation headed by Tarja Cronberg who is a member of the European Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee, its subcommittee on Security and Defence, and the Chair of the Iran delegation. It was this delegation that extended the now cancelled invitation to Iran’s parliamentary members to visit Europe. Mamedov agreed to talk to me in his private capacity and emphasized that the views expressed here are not necessarily the position of the Social-Democrat Group or the EP.

Farideh Farhi: Before discussing the politics of the EP resolution that was just passed, can you elaborate on the powers of the EP and the role it has in EU foreign policy decision-making? Does it have significant powers to influence the policy direction of the European Union or is the message mostly a statement of sentiments?

Eldar Mamedov: The EU, as a union of 28 nations, has a complex institutional architecture. All essential foreign policy decisions are taken by the Council of the EU, the institution representing EU member state governments. That’s where ministers from each member state meet and decide on laws and policies.

After the major reform of the EU in 2009 known as the Lisbon Treaty, the EP has acquired new powers on foreign policy. In addition to its power over the EU budget, including the foreign policy appropriations (which it already had before 2009), it can now grant or withdraw consent to international agreements concluded in the name of the EU with other countries. That means that if, for example, the EU signs a trade agreement with Iran it must be ratified by the EP.

But EP positions on foreign affairs carry weight, even if they are not legally binding, because they are expressed by the only directly elected body of the EU and therefore are considered important political messages.

Q: Since the election of Hassan Rouhani, two EP delegations have visited Iran. The EU’s foreign policy chief Catherine Ashton also visited Tehran in March. These visits suggested a desire to recalibrate Europe’s relationship with Iran. What explains the EP’s decision to adopt a resolution at this time?

This is not the first EP resolution regarding Iran. There have been many others that call on Iran to improve its human rights record. But this one tried to set a new tone.

The previous EP report on EU strategy on Iran, known as the Belder report, was adopted in 2011. It was a hawkish report drafted by a rapporteur known for his close links to Israel. It called to maintain and expand the sanctions regime against Iran, condemned Iran´s regional policies and scarcely outlined any areas of possible cooperation. The overall context — Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s presidency, the post-2009 election crackdown — made it very difficult for supporters of engagement to press their case. After the election of Hassan Rouhani as the president of Iran, and especially after the Geneva interim nuclear deal on 24 November 2013, prospects for the normalization of relations between the West and Iran improved and it was felt that the time has come to adjust the EP’s position to the new situation and make a constructive contribution to EU policy on Iran. The Parliament is in a better position to do so than the European External Action Service (EEAS), which operates under the authority of the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Catherine Ashton or the Ministerial Council, where taking bold steps requires lengthy and complicated negotiations, and where some big countries, such as the UK and France, have a tough approach to Iran.

The Socialists & Democrats Group (S&D), the main progressive group in the Parliament, stepped in and assumed initiative on the Iranian file. In October 2013, even before the Geneva deal, a delegation of the S&D led by its president, Hannes Swoboda, visited Tehran and held talks with Iranian officials, including former President Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani and the Speaker of the Parliament, Ali Larijani. This was the first visit from the EP to Iran in 6 years. Subsequently the S&D’s Spanish member Maria Muniz became the rapporteur on Iran and prepared the first draft for consideration in the Foreign Affairs Committee.

Q. The way you describe it, there was quite a bit of political wrangling regarding the language of the resolution, and the intent was to push for improved relations with Iran rather than reiterate the EP’s concerns regarding Iran’s domestic affairs. What was the process leading to the adoption of the report?

First, the rapporteur presented her draft. Then it was opened to amendments by different members representing their political groups. The method in the EP is to work on compromises between the original text and the amendments. Those amendments that cannot be deemed as covered by the compromise have to be voted on separately.

When the amendments were tabled, it became apparent that there were broadly two approaches: the forward-looking, constructive one advocated by the S&D rapporteur and other progressive groups, which included Liberals, Greens and United Left, and the one put forward by conservative groups such as the European People´s Party (EPP). The EPP includes Christian-Democrats and other mainstream centre-right political groups. It is the biggest group in the EP. Other conservative groups involved in this process included the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) with British Tories and associated right-wing allies, and the Europe of Freedom and Democracy (EFD), which includes far right groups such as the UKIP or Italy´s Northern League.

The conservative block sought to minimize or deny the positive elements of the resolution by using three strategies: 1) making any improvement in relations, however modest, conditional on a final and comprehensive nuclear agreement; 2) while welcoming the Geneva deal, emphasizing that Iran is still in violation of several United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolutions; 3) questioning the legitimacy of Rouhani as the president of Iran by pointing to the “non-democratic nature” of Iran’s elections and associating him with the steady rise in executions during the last few months.

In its most extreme form, the conservative line dismissed the Geneva deal for allowing Iran to preserve its enrichment activities and called for continuing a “robust sanctions regime” (language used by the EFD). The EFD also asked to defend the Persian Gulf Cooperation Council countries from the Iranian threat. Interestingly, conservative group members (some of them with links to the exiled Iranian opposition group, the Mujahadeen-e-Khalq (MEK), such as Spanish EPP member Alejo Vidal-Quadras and British ECR member Struan Stevenson) proposed amendments deleting the call for an opening of the EU office in Tehran, fully in line with the position of their supposed enemies — Iranian hardliners.

It must be said that not all in the EPP held such a hawkish position, but the hardliners were better mobilized to press their case than the moderates. This allowed them to win the internal EPP debate.

For the rapporteur and the progressives, the conservative strategies were not acceptable for several reasons. First, there are areas that require an urgent dialogue with Iran, such as ending the civil war in Syria and stabilizing Iraq and Afghanistan, which is why the EU can ill afford to postpone discussion of other issues except the nuclear one until after a final deal is reached. Besides, cooperation in areas of mutual interest may create trust and good will necessary for a successful final nuclear deal. Second, insisting on Iran´s violations of UNSC resolutions makes little sense when the same UNSC members plus Germany have negotiated the Geneva deal, which tacitly recognizes Iran´s right for limited enrichment. Thus, welcoming the Geneva deal and insisting on the UN resolutions is contradictory. Third, doubting the democratic credibility of Rouhani´s election serves no other purpose than to undermine his legitimacy, as does linking him with Iran’s sharp increase in executions, which is, by the way, under the purview of the judiciary, not the president.

Since the progressive and conservative blocks are roughly equal in the EP, there was a need to reach compromise on these issues to make the final text acceptable to the large majority.

Q: Can you explain the nature of compromises made in the final text?

The final text as adopted reflects the compromise achieved between the progressives and conservatives, but it is actually more progressive-leaning.

Here are some examples:

- The final text insists on simultaneous and reciprocal action from both sides to make sure the Geneva accord (the Joint Plan of Action) leads to a final deal. Reciprocity is the key notion here, instead of insisting on one-sided Iranian concessions.

- In a concession to the conservatives, the final text states that the presidential elections were not held in accordance with European democratic standards. But in the next sentence it refers to “President Hassan Rouhani” and acknowledges his readiness for more open and constructive relations between the EU and Iran. This means that the resolution recognizes Mr. Rouhani as the legitimate president of Iran.

- While the text does identify Iran’s nuclear activities as in contradiction to previous UNSC resolutions, it rejected (or did not include) the EPP/ECR amendment to the effect that the Geneva accord does not change the fact that Iran is still in violation of those resolutions.

- The text vocalizes EP support for the Geneva agreement and considers it vital for the comprehensive agreement to be reached within the agreed time-frame. It gives clear support for continued diplomacy even though a defeated EFD amendment criticised the Geneva deal and called for a “robust sanctions regime.”

- The text stresses that there can be no alternative to a peaceful, negotiated solution of the nuclear issue and that Iranian security concerns and sensitivities should be taken into account. The EPP wanted instead to have “the peaceful solution as the best solution.” Little nuance, but an important one: “no alternative to a peaceful solution” is stronger language than merely stating that it would be the “best solution”. And the notion that Iran has legitimate security concerns is also recognized.

- The text welcomes the decisions of the EU [ministerial] Council to partially lift sanctions — it also outlines the prospect of lifting nuclear-related sanctions altogether after the final deal is agreed.

- The conservatives’ desire to introduce strict conditionality linking any further improvement of relations with Iran to a final agreement on the nuclear issue was rejected. The final text only states that more constructive relations with Iran are contingent merely on progress in the implementation of the Joint Action Plan.

- The call for the opening of the EU delegation in Tehran was opposed by the conservatives but was approved for the final text.

- The final text calls on the Council of the EU to consider a number of important areas for cooperation with Iran such as a joint fight against drug trafficking, environmental protection, technology transfers, infrastructure development and planning, education, culture, and health. The EPP wanted to make this all conditional on a final agreement. But the text only states that it should be “subject to substantial progress in nuclear negotiations”, which is merely stating the obvious, but not adding new restrictive conditions.

- This text also expresses concerns over possible outbreaks of infectious diseases due to medicine shortages caused by the sanctions — a rather bold admission for an EP resolution.

- Concerns about the environmental situation in Iran are noted and there is a call for cooperation with Iranian scientists and environmental organisations.

- The importance of fostering trade with Iran is emphasized.

- The text calls on EU institutions not merely to increase exchanges of students and academics but to make a concerted effort to assist the process. This is meaningful, since too often different branches of the EU bureaucracy do not coordinate their actions sufficiently.

- The text calls for a more independent EU policy towards Iran. This is a very important statement, meaning mainly not to simply follow US policies.

- The text calls on Iran to be involved in all discussions on ending the Syrian civil war. “All” implies Iran’s inclusion in the Geneva II process. Conservative amendments only condemned Iran for its support for the Assad regime.

- The text encourages the EU to facilitate dialogue between Iran and GCC countries. In contrast, a defeated EFD amendment called to protect the GCC from the Iranian threat.

- The text calls for joint efforts in Afghanistan — again, an EPP amendment tried to delete this part.

Q: And what were the compromises related to human rights in Iran?

This is the most critical part of the resolution. Both progressives and conservatives agree that the human rights situation in Iran continues to be unacceptable. But there are still nuances. The text acknowledges the release of some political prisoners, including the Sakharov prize awardee Nasrin Sotoudeh, by the Rouhani government. It also “notes with interest” President Rouhani´s initiative on a new “citizenship chapter”.

It calls on Iran to issue a visa to the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Iran Ahmad Shaheed, which Iran doesn´t like, since it doesn´t accept that its human rights record is bad enough to warrant the appointment of a special rapporteur. It also calls on the UN HR High Commissioner Navi Pillay to accept Iran´s invitation to visit the country.

The most offensive part according to the Iranians is the language interpreted as obliging EP delegations visiting Iran to meet with dissidents. But this is a standard practice in the EP, and Iran is not being singled out on this. Moreover, the resolution does not make any future visits to Iran conditional on such meetings, but merely recommends to future delegations “to be committed” to meeting the opposition and civil society representatives. This is a recommendation and a wish, not a condition. Besides, the next European Parliament will decide on future delegation visits on a case-by-case basis.

Q: How has the EP’s views on Iran’s human rights record been shaped?

The information used in the resolution comes from respected human rights organizations that focus on Iran, such as the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran, the Iran Human Rights Documentation Centre, and the Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation.

While some EP members might have close ties with the Israeli government or the MEK, this had a negligible effect on the human rights chapter of the resolution. Iran’s high number of executions and discrimination against LGBT people and Bahais are universal concerns in the EP.

Q: Is Iran singled out on human rights?

No. The EP issues critical resolutions on human rights and democracy even on its own member states. Hungary is a case in point. Also on allies: in 2005-2006 there was a whole special committee to investigate Guantanamo and secret rendition flights and prisons in the context of the “war on terror”.

This March the EP adopted a strongly critical report on Saudi Arabia (with S&D MEP Ana Gomes as the Rapporteur). It was actually more critical than the recent resolution on Iran: it criticised Saudi Arabia for its role in promoting Wahhabism/Salafism worldwide and supporting extremist forces in the Middle East and elsewhere.

Q: But reports are different from resolutions, no?

The difference is merely procedural. Resolutions are prepared faster, but in terms of the political status and impact, there is no difference. The final text should be measured not against what would be ideal, but against the political realities and correlation of forces in the EP. As such, it is always a result of compromise and debate. From this point of view, this was the most forward-looking text on Iran that this Parliament has ever produced.

Q: Given that this is not the first time a resolution has been adopted, why do you think it created such uproar inside Iran this time while previous resolutions were ignored? Given the cancellation of the Iranian delegation’s visit, do you think the progressives’ efforts to pave the way for improved interactions with Iran may have ended up being counter-productive? The way it sounds, the intention was to change the direction of the EP, but perceptions in Iran, devoid of context, were otherwise. Is this a dilemma for EP progressives?

The reactions in Tehran were not surprising, but we now have dialogue, which didn’t occur in the past. When you talk to people, you also receive reactions. So, it might sound counter-intuitive, but in a way these reactions testify to the progress that we´ve been able to achieve in recent months.

That said, these reactions are mostly about politics in Iran. The conservatives use the resolution to embarrass the reformists and moderates who support engagement with Europe and US. We have exactly the same situation in Europe: our hardliners attack the progressives as the “appeasers of mullahs”. Both European and Iranian hardliners converge in one point: they don´t want a more constructive relationship between Europe and Iran. But Iranian conservatives and hardliners are not the only target audience of this resolution. The reformists and the moderates have noticed the positive elements in it. I think it would be a great idea to translate this resolution into Persian so that the Iranian people might draw their own conclusions.

In any case, even if some factions strongly disagree with the resolution, cancelling the visit of the Iranian parliamentarians to Europe was a bad idea. If you want to make a point, you have to talk. In the absence of dialogue, the only winners are groups like the MEK, who organised a conference in the European Parliament to use the reactions to the resolution as supposed “proof” that nothing has changed in Tehran.

Photo Credit: © European Union 2014 – European Parliament

]]>by Farideh Farhi & Jasmin Ramsey

Editor’s Note: Following is Jasmin Ramsey’s introduction and interview with Farideh Farhi, an independent scholar and expert on Iran from the University of Hawaii who has been in Tehran since the end of August.

The Iranian President Hassan Rouhani was inaugurated [...]]]>

by Farideh Farhi & Jasmin Ramsey

Editor’s Note: Following is Jasmin Ramsey’s introduction and interview with Farideh Farhi, an independent scholar and expert on Iran from the University of Hawaii who has been in Tehran since the end of August.

The Iranian President Hassan Rouhani was inaugurated just three months ago and two important historic events have already occurred under his watch: the private meeting between Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif and Secretary of State John Kerry on the sidelines of September’s UN General Assembly in New York and President Barack Obama’s 15-minute phone conversation with Rouhani on Sept. 28.

The hope that was generated in New York — where Rouhani and Zarif effectively presented Iran’s new administration to the world — carried through into the Oct. 15-16 resumed talks in Geneva between Iran and the 6-world power P5+1 team. While all parties have remained officially silent on the details of those talks, Iran, the US and the EU concluded with positive statements.

At the very least, it was obvious that Iran’s new negotiating team, led by Zarif — a well-known diplomat with demonstrable knowledge of the US and how to solve political quagmires — has entered negotiations with a serious plan and intent to resolve the nuclear issue once and for all. Of course, Iran and the P5+1 insist on certain bottom lines and it remains to be seen whether the stars will align in Tehran and Washington enough to allow a deal to happen. With that in mind, I spoke by phone with the Iran expert Farideh Farhi, who’s currently in Tehran, to get a sense of where things stand ahead of the next round of talks scheduled for Nov. 7-8 in Geneva.

Jasmin Ramsey: What is the political environment like in Iran right now in relation to the nuclear issue?

Farideh Farhi: A good part of the Iranian political spectrum is supportive of their nuclear negotiating team’s different approach and efforts for resolving this issue. The folks who are not supportive of this effort are effectively marginalized because of the presidential election’s results; the only argument that they have at this particular moment is: “it’s not going to work.” They’re hedging so that if the talks fail, they can come back and say: “we told you so.”

Does that raise the stakes for the Rouhani administration?

This government has a lot riding on the resolution of the nuclear issue because it made it a campaign promise and priority. Had Mr. Rouhani’s rival, Tehran mayor Mohammad-Baqer Qalibaf, been elected a failure on the nuclear diplomacy front would have posed less of a problem since Mr. Qalibaf’s campaign platform was more focused on the better management of Iran’s economy. But Rouhani’s campaign promise, as well as a quick jump on the nuclear issue, has raised the stakes for him and his foreign policy team (failure on this front may also end up impacting his promises on the domestic front). This is not to say that Rouhani is ready or desperate to make any deal in order to save his presidency or his other agenda items. The Iranian political environment continues to make the acceptance of an agreement that does not acknowledge Iran’s rights under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) impossible. So, the acceptance of a bad deal is politically even more dangerous for Rouhani than not reaching an agreement.

Are the Iranians reasonable in terms of what they are expecting from the other side as part of a mutual deal?

While discussing the complex web of sanctions that have been imposed on Iran, Iran’s Deputy Foreign Minister for Europe and Americas, Majid Takht-Ravanchi, argued that in exchange for Iran’s confidence-building moves, at least one of these sanctions should be removed as a first step. This suggests that Iran will not be asking for the removal of all sanctions immediately, as it has done in the past, but is looking for something that will show a change of direction in the U.S. approach to this issue. A reversal of the sanctions trend is important for selling whatever compromises the Iranian nuclear team makes to its audience back home.

As I mentioned previously, this government has a lot riding on this issue and if it is unable to frame the results of the negotiations as also protective of Iran’s rights, then it will not only be unable to sell the agreement domestically, it will also begin to face serious challenges regarding its domestic agenda.

Can you elaborate?

Mr. Rouhani’s election platform had three prongs. One was related to foreign policy; he promised a reduction of tensions with the Western world at least partly through successful nuclear negotiations. Then there was the economic prong, which has a management component. Against the backdrop of deteriorating economic conditions, Rouhani promised both better management of the economy and more rationalized state support for the private sector and productive activities. Finally, he called for the de-securitization of Iran’s political environment.

The continuation and further tightening of the sanctions regime will force the private sector and producers in Iran to rely even more on the state for protection against a deteriorating economic environment and the challenges of getting around sanctions. It will also increase the threat perception of the political system as a whole and as such make the further easing of political controls more difficult.

What about what’s happening in Iran domestically. Earlier this month the daughter of a key opposition figure, Mir Hossein Mousavi — who’s currently under house arrest — was reportedly harshly harassed by a guard outside of Mousavi’s home. Can movement on the nuclear issue aid the de-securitization of Iran’s domestic environment?

If a movement on the nuclear issue ends up reversing the economic war that has been waged and eliminate the threat of military attack that keeps being issued against Iran, then it is not too outlandish to think of the further opening of the Iranian political system. It should be noted that the high participation rate in the presidential election has already had some impact in terms of reducing the systemic fears that motivated the terribly restricted political environment of the past four years. In other words, on the domestic front the move towards the center, supported by the electorate, has already eased tensions within the country. The removal of external threats is likely to further this process. But if Mr. Rouhani’s foreign policy agenda is blocked by the United States taking a maximalist position, then there is no guarantee that this process will continue. In fact, it is more likely that old fears about outsiders — and particularly the US — trying to foment domestic disturbances will once again resurface.

So President Rouhani definitely wants to relax the state’s hand in the personal lives of Iranians?

He has certainly expressed his desire for a less interventionist state in the personal lives of the citizenry as well as a less repressive state in the treatment of critics and dissidents. His Intelligence Minister even said recently that dealing with security issues through securitizing the political environment is not something to boast about. So the expression of desire and/or pretense is there.

But there has been more than an expression of desire or hope. As I mentioned before, the political environment has also opened up considerably since the election. No doubt hundreds of political prisoners, including former presidential candidates, remain. Abuses such as the one you mentioned regarding Mousavi’s daughters also continue to occur. Just last week, a reformist newspaper was shut down for an article that should have been challenged through a critical engagement rather than shutting down a whole newspaper. Still, I arrived in Tehran two months ago and have yet to meet someone who does not acknowledge a vastly different political environment than prior to the election. This may be just temporary given how bad things were after the 2009 election, but there is nevertheless a palpable and acknowledged sense of relief and political release.

President Rouhani and the Iranian nuclear negotiating team have referenced a limited timeline for reaching a deal. How long do you think it will be before they say too much time has passed?

The process has become accelerated, but I don’t think anyone is expecting the sanctions regime to crumble within 6 months. People have even talked about some sanctions remaining for a long time — they reference the sanctions on Iraq and the time it took for them to be lifted. Nevertheless, there is expectation or hope regarding a reversal of these deteriorating trends.

The bottom line is that a good part of the Iranian population as well as the leadership is ready for a compromise. Under these circumstances, there is readiness for a full-fledged process of give and take and as such, agreements to keep meeting are no longer deemed satisfactory. Hence the expectation that something needs to happen by the next meeting. I don’t think this necessarily means immediate major concessions from either side, but I do think that once the first step is taken, there is no reason why this process cannot become even more accelerated.

In a speech on Sunday, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei essentially voiced support for Iran’s nuclear negotiating team and told hardliners to hold back for now. Does this signal a shift on his part?

It does not signal a shift, but it does highlight two key elements of Iran’s approach to the nuclear talks. First, his words make clear that despite the noise made by the hardliners criticizing the negotiation team’s softness, excitement, and perhaps even gullibility, Zarif and his aides have full systemic support in their efforts to find a reasonable solution to the nuclear conflict — a solution that addresses both Iran’s bottom lines in relation to the right to peaceful uranium enrichment as well as western concerns regarding potential weaponization. Secondly, Khamenei’s words also made clear that Iran’s approach to negotiations is quite pragmatic. As he said, if the negotiations work, “so much for the better”, if not, Iran will carry on with a more inwardly oriented approach to its development. By giving full support to the negotiating team — led by the very popular Foreign Minister Javad Zarif — the Leader is positioning himself on the side of public opinion, which favors talks, while making sure that the same public opinion eventually does not consider him a stumbling block to a reasonable solution. Such a positioning will make it more likely that domestic public opinion will blame US unreasonableness, egged on by the Israeli government, and not inflexibility or lack of diplomatic acumen of a Zarif-led negotiating team if talks fail.

Do you sense that Iran’s hardliners are willing to support a nuclear deal?

It’s not a question of their willingness; despite the hardliners’ loud voices at this particular moment, they’re marginalized. A systemic go-ahead has been issued for the perusal of some sort of compromise that acknowledges Iran’s right to enrichment despite limitations on the levels and extent. The hardliners will come out of the margins if the Obama administration insists on the maximalist position of no enrichment that is being pushed by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu or is unable to offer any kind of meaningful sanctions relief in exchange for significant Iranian concessions.

So Rouhani is walking a fine line in trying to balance his foreign policy agenda on the nuclear issue with the tricky situation he’s dealing with politically at home?

No doubt, but I would say that at this particular moment, President Rouhani and his team have some leeway regarding how to frame an agreement because of the consensus that was generated by the election. I would even argue that their hands are less tied than President Obama’s, considering Congress’ hardline position on the sanctions regime.

On that point, it’s quite interesting, because on one hand there’s almost a sense among those who are hopeful here regarding negotiations that Obama needs help. But on the other hand there seems to be a tactical urge on the part of others to mirror US policy on Iran. So, while some would like to reduce expressions of anti-Americanism that have long been present in the Iranian public sphere through slogans, posters and so on, others argue that the pursuit of diplomacy while emphatically chanting “Death to America” is Iran’s version of the US’ dual-track policy of sanctions and diplomacy on Iran.

Do you think the taking down of anti-US billboards earlier this month in Tehran is part of that?

Yes, they were taken down by the Tehran municipality and that was apparently on Mayor Qalibaf’s order. I saw smaller versions of those billboards, calling on the Iranian negotiators not to trust the American negotiators, being carried by demonstrators on Nov. 4, the anniversary of the US embassy takeover.

The protest rally in front of the former US embassy was more robust this year as well. Many people showed up or were bused in and instead of avoiding “Death to America” chants, Saeed Jalili, the former nuclear negotiator and presidential contender, made the case that it is perfectly fine to simultaneously negotiate and chant “Death to America.” He added that the chant is not directed at the American people, only at the US government. There was a clear rhetorical play on the US’ dual track of sanctions and diplomacy; the underlying point was that chants of “Death to America” are not directed at the US public in the same way that both the Obama administration and US Congress make the claim that sanctions are not directed at the Iranian people.

There have been several reports recently that foreign commercial actors such as oil companies are thinking about how they could return to Iran in the event of a nuclear deal. Are you seeing any of that on the ground?

Not yet. The sanctions regime is still in full force. I was talking to an Iranian businessman the other day and he told me that he can’t even receive brochures through the mail from German companies because they fear they would be violating sanctions. Of course, he then told me how he gets around that issue byway of Dubai.

Iran’s Oil Minister Bijan Zaganeh has stated that the Petroleum Ministry is re-evaluating its terms and conditions for investment in the country’s oil and gas sector with an eye for offering better terms. He has also acknowledged conversations with some European companies but he said all of this is just at the level of initial talks. So, people do seem to be getting ready for something — the mood for now seems to be that things may work out well because people are also sensing some change in the Obama administration. That said, everybody remains extremely cautious; they know very well that things could also fall apart very quickly.

]]>by Jasmin Ramsey

Visit NBCNews.com for breaking news, LobeLog

by Jasmin Ramsey

Visit NBCNews.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy

Amazing things have been happening on the US-Iran front, which began to defrost following Hassan Rouhani’s presidential inauguration this summer. I’ve listed some of them in my last two reports for IPS News (here and here) but today’s news is monumental.

You’ve probably heard something about a letter exchange between Presidents Obama and Rouhani. Well, this has not only been confirmed by both administrations, we’re also learning some of the details now, which I touch on below. Before I do so it’s worth noting that after news of the letter exchange and ahead of the United Nations General Assembly next week where Rouhani will give a speech, Iran released today a group of political prisoners, including lawyer and human rights advocate Nasrin Sotoudeh, who ended a 49-day hunger strike in December 2012 after Iran’s authorities lifted a travel ban on her 12-year-old daughter. Here is Sotoudeh’s interview in English with CNN’s Christiane Amanpour and some truly heart-warming photographs of her reunion with her family.

As shown in the clip above, Ann Curry has also conducted Rouhani’s first interview with an American news outlet as Iran’s president, which will air on NBC’s Nightly News tonight at 6:30 EST. (I think Curry hasn’t been to Iran since 2011 when she interviewed former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.) Only bits of the interview have been released so far, and while Rouhani won’t likely say anything earth-shattering so early on, he did describe the “tone” of Obama’s letter as “positive and constructive“. Of course, yesterday Obama also described Rouhani in a positive light. ”There are indications that Rouhani, the new president, is somebody who is looking to open dialogue with the West and with the United States, in a way that we haven’t seen in the past. And so we should test it,” Obama told Telemundo. That’s a dramatic change in tone from White House statements marking Rouhani’s inauguration.

All this is good news and there’s going to be a lot of expert analysis on what it all means, but I can’t get into it now as I’m getting ready to travel to New York where I will be reporting on Obama’s and Rouhani’s speeches from the UN, among other things. For now, here’s an excerpt from Paul Pillar’s “The Stars Align In Tehran” (written before today’s exciting news), to keep in mind as these developments unfold:

The late Abba Eban, the silver-tongued Israeli foreign minister, once famously said that the Palestinians never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity. The circumstances, and Palestinian preferences and policies, that underlay his remark changed greatly long ago. But his apothegm might apply to much of the history of the U.S.-Iranian relationship. It would, tragically, apply all the more if the current opportunity is missed, either because of the ammunition being supplied to Iranian hardliners or because the side led by the United States simply does not put on the negotiating table the sanctions relief necessary to strike a deal.

Photo Credit: ISNA/Abdolvahed Mirzazadeh

]]>SUSRIS Editor’s Note: Over the last two years the twin crises in Egypt and Syria have placed a heavy diplomatic and security burden on leaders and policymakers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United States. Washington and Riyadh have worked closely [...]]]>

SUSRIS Editor’s Note: Over the last two years the twin crises in Egypt and Syria have placed a heavy diplomatic and security burden on leaders and policymakers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United States. Washington and Riyadh have worked closely to formulate responses to the unfolding catastrophes in these countries as well as complex national security troubles unfolding across the region. As with any bilateral relationship American and Saudi interests do not always coincide as has been displayed in the reaction to the coup and crackdown in Egypt. The prospects for a military response to the use of chemical weapons in the Syrian civil war only adds to the difficulties of forging a common approach to the new regional realities.

To provide context to these urgent issues SUSRIS called onAmbassador Chas W. Freeman, Jr., to share insight and perspective on the diplomatic consequences for Washington and Riyadh. Freeman’s distinguished career included service as US Ambassador to Saudi Arabia during Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm and as Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs. He was the President of the Middle East Policy Council and vice chair of the Atlantic Council of the United States. Freeman is Chairman of the Board of Projects International, Inc. We spoke with Ambassador Freeman by phone from his home in Rhode Island on August 27, 2013.

[SUSRIS] Thank you for taking time to talk about the crises in Syria and Egypt and the fallout for American ties with its allies in the region, especially the US-Saudi relationship.

All eyes have shifted from the coup and crackdown in Egypt and the American reaction to it, to the increasing likelihood that the United States will take the lead in a military response to last week’s use of chemical weapons in Syria. In what ways are there agreements and differences in the policies of Washington and Riyadh over Egypt and Syria?

[Amb. Chas W. Freeman, Jr.] There is actually a fair amount of convergence in short-term Saudi and American objectives with respect to Syria, but probably some divergence in long-term views, which we can get back to. At the moment there are serious divisions of opinion between the United States and Saudi Arabia that mainly find expression in our policies toward Egypt.

It’s no secret that the Royal Family in Saudi Arabia was shocked when the United States first vacillated and then withdrew its support from President Mubarak. This seemed to them to show that the United States was an unreliable protector. Obviously protection has been one of the services that the Saudi Royal Family has traditionally looked to the United States to provide. The Mubarak situation catalyzed Saudi reactions borne of over a decade of growing exasperation with U.S. policy. While the Saudis don’t want to give up the relationship with the U.S. – for some purposes the U.S. remains a valued partner, they have concluded that in many respects they’re on their own. They see they now have to act unilaterally in defense of their own interests, even when this puts them at odds with the United States.

Now we see a strong Saudi intervention in Egypt on behalf of autocracy. The effort to make the region safe for autocracy directly counters the American ideology of democratization. In the Saudi judgment, recent experience shows that democratization leads inevitably to the triumph of political Islam. Islamist democratism is a challenge to the legitimacy of the Saudi monarchy, which is based on the notion that in Islamic societies there is a religiously enlightened leader, an emir, who leads the Muslim community, the Ummah. While the emir’s leadership has to be responsive to opinion and political consensus, it is ultimately autocratic.

This idea contrasts with the western notion that sovereignty is or should be exercised from the bottom up through elections. So we have a fundamental disagreement on Egypt. We probably have the same disagreement, although less obviously, in the case of Bahrain. It was there that, from the Saudi perspective, the first effects of the Mubarak debacle in the Arabian Peninsula were felt.

The turmoil in Egypt has led to the emergence of some degree of entente between the Saudis and the Russians on the issue of autocracy and opposition to militant Islamist populism. The Russians see an opportunity in Egypt as the Egyptians reconsider their dependence on the United States – perhaps in part reversing the Egyptian switch to American protection that Sadat pulled off. The Russians may try to work with the Saudis, the Emiratis, and others wealthy autocracies in the Gulf to reestablish a military supply and strategic relationship with Egypt that would once again give them significant influence in the Middle East beyond Syria. This has clearly been discussed, at least in a preliminary way, between Prince Bandar bin Sultan and Vladimir Putin. So I think Saudi-American disagreements over Egypt are not trivial.

There are other sore points dating back to the invasion of Iraq. Some Saudis favored the invasion, but most at the top clearly did not. It badly backfired in terms of establishing a pro-Iranian, Shiite-dominated regime in Baghdad. The U.S. attempted for some time to broker rapprochement between Riyadh and Baghdad but I think it has now concluded this is impossible and given up.

There is also a difference in opinion between us about how much of a supporter Malaki is for the Assad regime in Damascus. And I don’t think the Saudis have lost their sympathy for the Sunni minority in Iraq or their desire to see it reestablish itself in a position of at least equality, maybe even more, in Iraqi politics.

In Syria, as I said, we have a short-term convergence of interest. We both wish to remove Syria from the asset side of Iran’s geo-strategic balance sheet. We both oppose Hezbollah. We both would both like to see Assad out. In the end, however, we may not agree about the future of Syria. The Saudis have a strong interest in the territorial integrity of Syria. The United States may not share that interest. Certainly Israel, our principle partner on these matters, does not. The Saudis may see a future Sunni-dominated Syria as a platform from which to remove Iraq from the Iranian orbit. I don’t think Americans have thought much about the implications of that.

There’s a lot of confusion and cognitive dissonance. Many things are in motion between the United States and Saudi Arabia with respect to the overall configuration of the region. The Arab uprisings were about Arabs re-seizing control of their own destiny. This began in Tunisia and Egypt and spread. It has now affected Saudi Arabia in the sense that the Saudis are also attempting to seize control of their own destiny and regional role, in both of which the US will necessarily play a diminished part.

[SUSRIS] Saudi and UAE officials were said to have warned the US Secretary of State of consequences for US ties, especially in the area of security concerns, over the question of American support for Egypt according to a Wall Street Journal article. King Abdullah warned that Saudi Arabia stood against those who tried to interfere in Egypt’s domestic affairs. You were quoted by Jim Lobe as saying, “The Al-Saud partnership with the United States has not only lost most of its charm and utility; it has from Riyadh’s perspective become in almost all respects counterproductive.” Yet, the Obama Administration engaged in weeks of verbal gymnastics to keep from calling the coup a coup and has so far only reacted with token measures against the bloody crackdown against the Muslim Brotherhood. Is there that much daylight between Riyadh and Washington on the Egypt issue to warrant such a high-pitched reaction?

[Freeman] Riyadh is very realistic. When Mubarak was removed from office there was the shock, which I described, and an absence – from the Saudi perspective – of a helpful and supportive American reaction. The Saudis embraced the new reality and tried to make the best of it, but then they saw several things happen which they didn’t like. First, in foreign policy Morsi reached out to Iran, which Saudi Arabia sees as its principle regional rival. Morsi’s government did not have the negative view of Hamas that Riyadh does. As the Morsi government proved to be incompetent, demonstrating that the Muslim Brotherhood and Islamists in general lack a coherent and effective economic philosophy or policy, Saudi Arabia saw Egypt drifting into anarchy and alignments that were contrary to its interests. Saudi Arabia very much welcomed and may even have encouraged the overthrow of Morsi. By any definition, notwithstanding the tortured legal fictions that prevail in Washington, it was a coup. The Saudis are pleased that the U.S. has not said that.

The Saudis do not want the United States to break with the al-Sisi government in Cairo. On the contrary, they would like the U.S. to support that government, as they do. Our support has been equivocal. The military aid relationship has not been solidly reaffirmed. It has been under review. Things have been moving on a case-by-case basis. American statements have — true to our values — continued to attempt to balance ideological commitments to democratization with our in interest in preserving the Camp David structure and the Egyptian cooperation with Israel, which are central to our position in the Middle East.

So we haven’t had an open break, but we’ve been very firmly warned by the Saudis. If we do suspend assistance, they will step in and repair whatever damage is done to the Egyptian Armed Forces. They have in effect deprived us of a considerable amount of leverage over the Egyptian Army.

This is the first time that I have seen so open, in fact much of any, open or concealed Saudi divergence from U.S. policy objectives. In the past the Saudi tendency has been to register objections but to refrain from undercutting U.S. policies they don’t like. Now they’re acting. And this goes back to the point I was making that they, like others, in the region have decided to take matters into their own hands.

Egypt has a history of switching sides, making dramatic readjustments in its strategic orientation. Ultimately that is what’s at stake here. The United States should exercise caution with Egypt. We could provoke a return of Egyptian strategic deference to Moscow. Of course, we’re not in the Cold War, and Russia is not our enemy. But it is a diplomatic rival, and were Egypt to return to military supply and training relationships with Russia under circumstances where the Egyptian army was running Egypt, this would have ramifications that go well beyond the question of our priority use of the Suez Canal or reliable transit rights over Egyptian airspace. I think that’s one element of this, but far from the only one.

[SUSRIS] How do the warnings from Saudi Arabia and the U.A.E. officials that security cooperation elsewhere in the region might be affected fit in here?

[Freeman] Well this is, of course, another issue. Let’s consider for a moment on a speculative basis, because that’s all it is at this point, what factors might go into a Saudi-Russian entente, maybe a Saudi-Russian entente including others in the GCC. First of all we need to remember that the strategic utility of the United States to Saudi Arabia in relation to Israel has been reduced. Our long default on peacemaking means that we are no longer on the right side of the effort to inhibit the Israel-Palestine issue’s radicalization of Arab politics. Moreover, it is obvious that we cannot control or even constrain unilateral actions by Israel against neighboring countries including, Saudi Arabia. So we don’t perform the protective roles we once did with respect to the region’s greatest military power.

Then, too, our actions in Iraq inadvertently strengthened Iran. We gave Iran a friendly and, in some respects, allied Iraq, instead of an Arab enemy that balances it. Iraq shares Iran’s interests, for example, with respect to Bahrain, which is a core Saudi security concern. We’ve also failed, from the Saudi perspective, to come up with an effective way of reversing, or even checking the growth in Iranian prestige and influence in the region. From Riyadh’s perspective, Iran is not just a nuclear issue although that’s part of it. In the case of Iran, many Saudis accuse us of errors of omission in addition to errors of commission in Iraq and Lebanon. So they don’t see us as they once did.

This brings us to Saudi and Russian interests. There are now many coincidences between them. First, both Riyadh and Moscow favor autocratic regimes. In Egypt the Russians may see an opportunity to regain influence with Saudi help. The Saudis may see an opportunity to offset objectionable American policies by either paying for or helping to arrange Russian arms transfers to replace those that we suspend or cancel. With respect to Bahrain, of course the Russians have no objection to Saudi or GCC policies. With respect to Iran, relations between Moscow and Tehran are good on a day-to-day basis but the two remain strategic rivals. Russia is in the region. It can’t come and go as we do. Russia has the potential capacity to balance Iran from the north, not in the Gulf, without the socio-political complications that our presence there entails.

Russia is also a historic rival of Turkey. Relations between Moscow and Ankara have never been better but their rivalry continues just below the surface. The Saudis are against the Turkish model of Islamist democratism and do not have an interest in advancing Turkish foreign policy objectives, especially in Egypt.

Finally, strangely enough, about twenty percent of Israelis are Russian so the Russians have some unexpended influence in Israel to bring to bear should it choose to do so. So the attractions of trying to work out a Saudi-Russian entente are there. By entente, I mean a framework for limited cooperation on a limited set of issues, perhaps for a limited period time.

There also are a lot of difficulties in the way of Saudi-Russian cooperation. Let me take one of them.

If you look at Syria the primary Saudi objective is to remove it from the Iranian orbit and undercut Hezbollah. Secondarily, they want to remove Assad from office. From the Saudi perspective, he has been dishonest, deceitful, and dishonorable. Riyadh would like to see him go and his regime with him. However, the primary objective is to eliminate Iranian influence and to undercut Hezbollah, which has emerged as the dominant political force in Lebanon, where it contests Saudi influence. There may also be a Saudi objective of using a reoriented Syria, as I suggested, to try to retake some or all of Iraq for Sunni Islam, reducing Iranian influence there.

Assad is a secondary issue. What the Russians have wanted to do in Syria in addition to protecting their commercial interests, their naval base, and their relationships with the Syrian elite, is to draw a contrast between their own stalwart support for the beleaguered Assad and the American abandonment of Mubarak. They want to show that they are a reliable protector and partner.

Syria is now de facto partitioned in many respects, and the Assad regime does not even control many of the elements that support it. In some cases they are taking on the characteristics of warlords or gang leaders, even self-financing with smuggling and extortion and protection rackets and other activities. The only way one could imagine Assad surviving after a graceful interval and being allowed to withdraw with dignity from a Syria he can no longer control is if the Saudis and the Russians cooperated to accomplish that. Depending on what was agreed, that could perhaps achieve the Saudi objective of cutting the Damascus’ ties with Tehran. It could also accomplish the Russian objective of not having Assad overthrown, but withdrawing with some dignity. This is a real long shot but not impossible to imagine.

So you could see a situation in which both sides gained from the strategic reorientation of Syria and from the orderly removal of Mr. Assad. I suspect that there will be some talk about this, although it appears the initial Saudi approach to the Russians was another effort to persuade them to do what Saudi Arabia would prefer, which is simply to get rid of Mr. Assad at the outset. That can’t have gotten very far but it is not necessarily the end of the story.

[SUSRIS] It was done in a surprisingly public way. Prince Bandar could have made his meeting with President Putin without posing for the cameras.

[Freeman] There are many games going on here, and one of them is a reminder to the United States that there’s more at stake than we tend to imagine.

[Freeman] There are many games going on here, and one of them is a reminder to the United States that there’s more at stake than we tend to imagine.

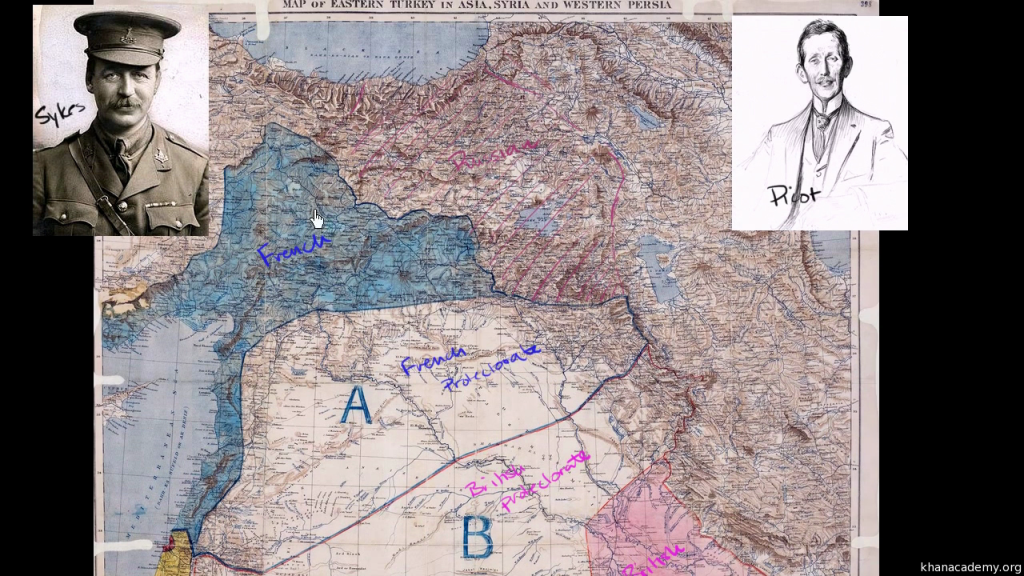

The world that has existed in the Middle East is changing. Mr. Sykes’ and Mr. Picot’s work is coming undone. Strategic orientations of the past cannot be taken for granted. Saudi Arabia itself has got its own interests and requirements for policy and cannot be taken for granted by the United States, as we’ve often tended to do.

Additionally, by going to Moscow, the Saudis undoubtedly hoped to unnerve Bashar Al-Assad and Tehran and put pressure on both.

Finally there’s another factor and that is Russia and Saudi Arabia – the two largest oil producers and exporters in the world – are concerned about how to cope with the resurgence of American production of oil and gas from shale and other unconventional sources. Apparently one of the things that was discussed was some sort of arrangement for coordination to sustain oil prices at what the two sides consider to be a reasonable level. This is another previously improbable but new and potentially significant subject for these two governments to explore.

[SUSRIS] Now that Syria has displaced Egypt in the headlines and Washington is ready to act against Assad is there likely to be a change in language about the disagreements or policy moving forward?

[Freeman] Both governments have an interest in sustaining an appearance of harmony and cooperation between them. What does it benefit either to appear to separate from the other, unless and until some major strategic deal that has advantages for one side or the other is struck? I wouldn’t expect either side to be very honest or forthcoming about what it thinks about the actions and activities of the other. Of course if the United States attacks Syria I expect the Saudis will be delighted since they have been urging a more active American support of the opposition and opposition to Assad for eighteen months anyway.

[SUSRIS] Is there a risk that a limited punitive strike, along the lines of what is being discussed, will do little to change the situation, the catastrophe that it is, and with Assad still in power?

[Freeman] Here we have to quite cynically recognize some realities. The first is that if the primary objective of both Saudi Arabia and the United States, and some other countries in the region, is to remove Syria from Iran’s embrace, then anarchy and mayhem are the next best thing to regime change.

The case has been made, most recently in the New York Times by Edward Luttwak, that the United States would lose if either side won. Therefore, the argument goes, the best thing is for the fighting to go on. Now that of course is a reminder of some of the more absurd elements of the “red line” about the use of chemical weapons. In a week where the Egyptian army killed a thousand people, the Syrian government was accused – rightly or wrongly, we don’t know – of having killed three or four hundred people, as if it was the use of the weapon involved, not the deaths that really mattered. One hundred thousand people or more have died in Syria with the United States and others doing very little of an overt nature. The international community remains divided on this subject. Some might argue that it displays an odd set of humanitarian priorities.

So, this is one set of issues. Another is that this effort to use precision strikes to alter the situation on the ground in Syria is unlikely to be effective. Look at what has happened in Syria. A very fractured opposition now confronts an increasingly fractured regime, with militias operating under local warlords or gang leaders. They are carrying on a great deal of their struggle not so much in support of the regime as in defense of the ethnic communities that depend on the regime — the Christians, the Alawites, secular groups who don’t like the Islamists who dominate the opposition.

It’s entirely possible that a strike on chemical weapons facilities would result in the degradation and devolution of control over the chemical weapons to these warlords and feudal barons, meaning that it would further dilute the government’s control of chemical weapons, and greatly increase the probability of their use by people without the knowledge or support of whatever regime remains in place in Damascus.

This is an extremely dangerous situation. Far more dangerous still is the question of what follows the Assad regime. And here is where I think the United States and Saudi Arabia may turn out to have some serious differences. The Saudi tolerance of Salafi Muslims is a great deal higher than that of the United States. After all, Saudi Arabia is officially Salafi. And while we have a common enemy in Al-Qaeda, the Jihadi elements who attack us also attack Saudi Arabia, or perhaps it’s the other way around – those who attack Saudi Arabia also attack us. To the extent there’s daylight between the United States and Saudi Arabia, their incentive to focus on Saudi Arabia rather than the United States goes down. That is to say that the probability of a Jihadi focus on the United States goes up. That would be an ironic result indeed of what I take to be an effort by the Saudis in Syria and Lebanon to reduce the danger of terrorism against their own society.

[SUSRIS] Let’s return to the U.S.-Saudi relationship. The partnership is much more complex than any one element of the security component. Let’s look at US-Saudi relations in their totality, and the history of recurring ups and downs, in the past you referred to it as being a marriage. How would you describe the playing field going forward, looking at the scope of business ties and all of the things that are held as being values in the relationship?

[Freeman] It’s a much more fluid and dynamic relationship now than it was, with many things in motion going in different directions. It’s more like a polo field than it is like the stable relationship characteristic of marriage. There are a lot of gopher holes in the field that can break the legs of the horses who are playing the game.

If you look at the various interests that have brought us together, there is the tradeoff of energy for security. As I’ve pointed out the Saudis no longer have much confidence in our ability to deliver security for them. They also see us, I suspect, as an increasingly problematic factor in global energy markets given our rapid ramp up in oil production and our gas exports. The question of cooperation on Islamic issues has been moot for quite a while. We’re very much at odds on that, although I continue to believe that under King Abdullah there have been major opportunities for us to cooperate with the Saudis in pulling the fangs of the Jihadi movement, which we have not seized. It’s a tragedy that we have not done so.

We have a continuing interest in freedom of transit through the air and sea space in the Arabian Peninsula and around it as the discussion of Egypt in the Wall Street Journal that you cited brings out. That continues on a case-by-case basis with no overall framework that guarantees it. It’s clearly related to Egyptian decisions on these matters and perhaps cannot be taken quite so much for granted as in the past.

The Saudis continue to use their connections to the United States, I think very wisely and skillfully, to expose a younger generation of lower-middle class Saudis to come to the modern culture of the United States. There’s a huge number of students here under the King’s scholarship program.

The U.S. continues to be a very significant presence in Saudi commercial markets but in terms of market share we have been a diminishing presence. In every respect we are not the destination for Saudi oil exports we once were. We’re not the source of imports we once were. Others have a greater role.

With respect to cooperation in foreign policy, the Saudis are clearly looking around for ways to dilute what they regard as over-dependence on the United States. This is not a particularly promising arena for cooperation in the short term.

Finally, cooperation on counterterrorism brings us squarely to the irony that it is in many respects Saudi closeness to the United States, and therefore to American policies on issues like the Israel-Palestine issue, that makes Saudi Arabia a target for Islamist terrorists. Therefore, the closer our cooperation, public cooperation, arguably the greater the cost it will be to Saudi Arabia in this arena. Nevertheless, we do have the same enemy, and I would expect our cooperation to continue, though perhaps with less publicity.

To sum all this up I would say that neither side can do without the other, or wants to do without the other, but the Saudis are much more prepared than in the past to reduce their reliance on the United States and to seek new partners and new directions.

[SUSRIS] Can you remember any point in American diplomatic history where there has been such a convoluted collection of circumstances as we see now in the Middle East?

[Freeman] Last fall I gave two speeches on the changing world order, one called“Paramountcy Lost” [Challenges for American Diplomacy in a Competitive World Order] the other called “Nobody’s Century” [The American Prospect in Post Imperial Times]. The key point is that it’s not just the Middle East but everywhere there is a decentralization of political and economic power. Militarily we Americans are still unmatched but in the other spheres we now have effective rivals on the regional and sometimes even on the global level.

The complexity of foreign affairs now requires a level of agility from Americans that we have not historically displayed. We’re good at wars of attrition and the diplomatic equivalent of trench warfare, not blitzkrieg.

What we are confronting now is the possibility, still just a possibility, still reversible, that the entire landscape in the Middle East that we have been accustomed to, could be rearranged by some geostrategic earthquake.

I think there is a broader context here. The Saudis are looking out for their interests first, in a way that frankly they did not in the past. The Saudi concept has been that friends defer to the interest of friends. Since the United States does not defer to anyone else’s interests these days, not surprisingly, Saudi expectations and behavior are different now. We have interests that differ from theirs. They are not treating us with the deference they once did. They are pursuing their own interests and policies. I think we need to reexamine our own interests. I think our interests dictate a strong relationship with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia but some of the policies we have followed in the Middle East have clearly been counterproductive and others have been ineffectual. We need to rethink things.

]]>by Jasmin Ramsey

Almost 1,000 Egyptians have died, according to the official count, since Aug. 14 when Egypt’s armed forces began clamping down on Muslim Brotherhood-led protests against the military ouster of President Mohamed Morsi. That number well exceeds the 846 people who officials say died during the 18 days of protest [...]]]>

by Jasmin Ramsey

Almost 1,000 Egyptians have died, according to the official count, since Aug. 14 when Egypt’s armed forces began clamping down on Muslim Brotherhood-led protests against the military ouster of President Mohamed Morsi. That number well exceeds the 846 people who officials say died during the 18 days of protest that ended Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year rule in Jan. 2011.

The democratically elected Morsi, a leading member of the MB, has not been seen in public since Jul. 3. But Mubarak has been released from prison into house arrest while he faces retrial. Egyptian media has for the most part adopted the language of the army in framing the unrest — Muslim brotherhood members are alleged “terrorists” who are trying to destroy the country.

While the US, who the Egyptian media claims conspired with the Brotherhood, has cancelled military exercises with Egypt and urged both sides to halt violence, it has so far resisted calls for halting military aid to its strategically positioned ally.

The rapid turn of events in Egypt, from a revolution to perhaps a “counterrevolution”, has left US President Barack Obama in quandary. Having eventually supported the fall of Mubarak, the US looks hypocritical in continuing its relationship with the military as authoritarian rule is restored.

In an interview with IPS, Emile Nakhleh, the former director of the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) Islamic Strategic Analysis Program, explained why repression will not prevent the Muslim Brotherhood from continuing its existence as a rooted, cultural and political force. Continued repression could also push the Brotherhood’s younger members to embrace violence as a political tool.

The US should pursue its own interests in Egypt, which “do not necessarily equate with dictatorial repressive regimes,” the Middle East expert told IPS. “In the long run, democratically elected governments will be more stable than these autocratic regimes.”

Q: There are different accounts circulating, especially in the Egyptian media, about what the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) actually is. Can you provide some background?

A: The Muslim Brotherhood was founded in 1928 as a social, religious, educational, political and partly military movement. It was founded against British colonialism and with it came the fight for Palestine, starting in the early 30s. Its main ideology is as follows: Islam is the solution. And the 3 D’s in Arabic, which translate to Islam is faith, state and society. There is to be no separation between the mosque and state in any of these.

The Muslim Brotherhood spread more than any other party in the Middle East in the last 85 years. It focused heavily on Islam, but took all those other things into consideration. And then of course they got involved in politics. That put them in conflict with the monarchy at the time. In 1948 this conflict became violent. Muslim Brotherhood members assassinated the Egyptian Prime Minister and in turn, the regime assassinated the founder of the MB in 1949.

By the mid-90′s, the Brotherhood decided to forgo violence and move toward their original mission, Da’wa, to proselytize their doctrine by Islamizing society from below. They wouldn’t allow themselves to be removed by force; they saw what happened in Algeria in 1991 and redirected their ideology to society itself, modeled after that American baseball-feed ideology, you know, you build it and they will come. So you Islamicize society from below and once society becomes Islamicized, you can establish a position in government and become a Shari’a-friendly government.

This process started in the late 80s, when the MB entered 4 or 5 parliamentary elections as independents or in alliance with other parties, such as the Wafd Party and the Labor Socialist party. Why? Because the government passed Law 100, which prohibited religious parties from participating in politics.

In the 2005 election, the MB won 88 seats in parliament, the largest ever for the MB. But they ran as independents. They emerged as the largest opposition party in parliament after Mubarak’s ruling party. In their 85-year history, the MB has been banned and repressed by regimes — from King Faruk to Mubarak; that’s why they’re not going away. They’re part and parcel of the religious foundation of Egyptian society.

With every regime Egypt has had since 1948, the relationship with the MB has always initially been good and then soured toward the end. Gamal Abdel Nasser was the same. He reached out to the Muslim Brotherhood in 1954 and by 1955-6, when a plot to assassinate him was uncovered, the Muslim Brotherhood was repressed and exiled. Then in 1966 Nasser’s government hanged one of the MB’s conservative thinkers, Sayyid Qutb.

Q: Is that what’s happening now, with the army’s arrest of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Supreme Guide, Mohamed Badie?

A: Qutb was actually more of a radical thinker than the mainstream MB. It’s also very interesting to note that a number of MB activists were exiled to Saudi Arabia where they established a more radical view of Islam. That view led Saudi Arabia to oppose Nasser’s actions in Yemen and other Arab nationalist projects.

Q: The Saudis welcomed the MB because they were Salafis?

A: The Saudis welcomed the MB with open arms because they were Salafis and because they were opposed to the secular Arab nation ideology that was preached by Nasser. The MB’s relationship with Nasser soured until 1970 when Nasser died and Anwar Sadat came to power. Sadat also began to court the MB as a countervailing force against leftist and Nasserist nationalist ideology.

The MB’s influence really began in the 1970s when they reconstituted themselves as a religious party that underpinned society. The constitution reflected Islam and allowed them freedom to preach and participate in associations, so much so that by the 1980s, the MB, through elections, controlled almost every professional association and university student council.

That scared the hell out of Hosni Mubarak, who also tried to court the MB in the beginning. It was, by the way, Mubarak who approved a change in the constitution to say Sharia is the source of legislation.

General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s game is thus very dangerous. It will fail because the MB is the most organized and the most disciplined in Egypt and because they have been used to repression from Farouk to Nasser to Sadat and to Mubarak. Sadat allowed the MB to reconstitute itself and invited MB exiles to return home, but by the late 1970s, the MB broke with Sadat because of his trip to Jerusalem and the peace treaty with Israel. At that time, the entire Arab world broke with Sadat.