by Jasmin Ramsey

The title of this post is a quote from Shaul Bakhash, a George Mason University professor who moderated a panel discussion, “Iran, the Next Five Years: Change or More of the Same?“ at the Wilson Center today. “In a way, we’ve been here before,” said the esteemed scholar, referring [...]]]>

by Jasmin Ramsey

The title of this post is a quote from Shaul Bakhash, a George Mason University professor who moderated a panel discussion, “Iran, the Next Five Years: Change or More of the Same?“ at the Wilson Center today. “In a way, we’ve been here before,” said the esteemed scholar, referring to the presidencies of centrist leader Hashemi Rafsanjani and Mohammad Khatami, when the country was perceived as moving towards openness at home and abroad. But while Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s administration includes individuals with past ties to those movements, Bakhash says the conservatives “remain the strongest political body in Iran”.

While nothing can stay the same forever, many people worried (some still do) that the Islamic Republic would continue down a path of conservatism verging on radicalism before the surprise presidential election of Rouhani in June 2013. Since Rouhani took over from Mahmoud Ahmadinejad — whose former conservative allies couldn’t effectively unite in time to support another conservative into the presidency — those worries have changed. Now the question on everyone’s mind is: can Rouhani successfully navigate Iran’s contested political waters in his quest to implement foreign, economic and social policy reforms?

A lot depends on Iran’s 2016 parliamentary elections, according to panelist Bernard Hourcade, an expert on Iran’s social and political geography. “Elections matter In Iran”, said Hourcade, echoing Farideh Farhi. What happened in 2009 (when large groups of Iranians protested the election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and were violently repressed) proved that “elections have become a major political and social item in [Iranian] political life.”

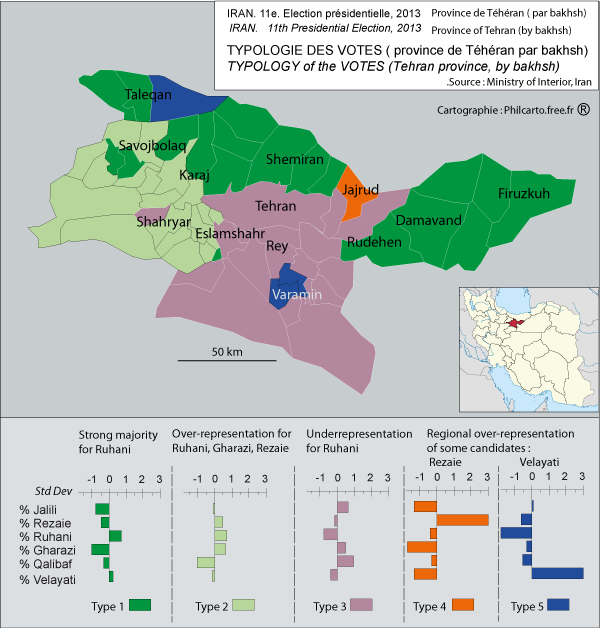

Hourcade uses official data to back up that point. Most interestingly, he shows that due to population migration patterns, the most important political divisions no longer exist between Iranian cities and villages, but between city centers and suburbs. Consider, for example, the typology of presidential votes for Rouhani in Tehran province. Hourcade’s diagram shows that while Rouhani had strong support in the northern part of Shemiran, he didn’t get a majority in central Tehran. Why that occurred is more difficult to answer, according to Hourcade, due to limited data resources.

Hourcade uses official data to back up that point. Most interestingly, he shows that due to population migration patterns, the most important political divisions no longer exist between Iranian cities and villages, but between city centers and suburbs. Consider, for example, the typology of presidential votes for Rouhani in Tehran province. Hourcade’s diagram shows that while Rouhani had strong support in the northern part of Shemiran, he didn’t get a majority in central Tehran. Why that occurred is more difficult to answer, according to Hourcade, due to limited data resources.

How political divisions play out in Iran’s upcoming parliamentary elections, which could give Iran’s currently sidelined conservatives more power, will also impact the Majles’ (parliament’s) reaction to the potential comprehensive deal with world powers over Iran’s nuclear program.

In other words, even if Iran’s rock star Foreign Minister can negotiate a final deal with the P5+1 (the U.S., Britain, France, China, and Russia plus Germany) that Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei approves, Iran’s parliament still has to ratify it, and if conservatives who oppose Rouhani dominate the majles, we may have another problem on our hands.

There were many other important points offered by Hourcade and his co-panelists, including Roberto Toscano, Italy’s former ambassador to Iran. He noted that former President Mohammad Khatami didn’t have the same chances as Rouhani because he was “too much out of the mainstream”. Rouhani, a centrist cleric and former advisor to Ayatollah Khamenei, wouldn’t have won the presidency without pivotal backing by both Khatami and Rafsanjani. So, as Toscano argues, Rouhani is in the mainstream (for now). But whether he and his allies will be able to maintain support from these important players moving forward, especially in 2016, will seriously influence whether he, like Khatami and Rafsanjani will be ultimately sidelined, or achieve a presidential legacy in Iran like nothing we’ve seen before.

Photo: Iranian President Hassan Rouhani walks by former Presidents Mohammad Khatami and Hashemi Rafsanjani following his June 2013 presidential vicotry. Credit: Mehdi Ghasemi/ISNA

]]>by Farideh Farhi

Paul Pillar has aptly explained why the vote this week in the House of Representatives for even more sanctions against Iran (H.R. 850) is at odds with the stated US foreign policy objective of changing Iran’s nuclear policies. While the Senate is unlikely to go along, at [...]]]>

by Farideh Farhi

Paul Pillar has aptly explained why the vote this week in the House of Representatives for even more sanctions against Iran (H.R. 850) is at odds with the stated US foreign policy objective of changing Iran’s nuclear policies. While the Senate is unlikely to go along, at least for now, the vote brings into question the motives for such a move.

I do not know whether the folks in the House wanted to remain in the good graces of the pro-Israel lobby, AIPAC, as Ali Gharib and M.J. Rosenberg suggest, or if they really do want to block any possibility of a deal with Iran to hasten regime change — which State Department folks keep telling me is not the official and stated policy of the US government. The bottom line is, however, that the motives are irrelevant to the chilling effect the vote’s outcome will have on negotiations and Iran’s skepticism about the Obama administration’s ability to “have the sanctions gone in a moment if it will substantively and constructively negotiate with the P5+1” as stated last month by Wendy Sherman, the US Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs.

The vote is undoubtedly a signal that members of Congress are more interested in making the Iranian government cry uncle than negotiating. That’s not a smart move if the US government’s objective and stated policy is to convince Iran to limit its nuclear program and subject it to a more robust inspection regime. And let’s be clear: the message is not only to the Iranian government; it’s also to the Iranian people.

There is really no going around it. The House’s vote also shows the proverbial middle finger to the Iranian electorate, who went to the polls on June 14 in large numbers to the tune of 73 percent — a significantly higher participation rate than in years of US presidential elections — and voted for someone who was an unlikely victor because of his stated desire to reroute Iran’s foreign policy and improve relations with the world. That same electorate then treated Hassan Rouhani’s victory as a reflection of its will by celebrating in the streets.

Just to reiterate, in addition to the systemic odds against him, Rouhani was elected by an Iranian public who refused inaction despite the results of the contested 2009 election and the repression that followed. Prodded by two former presidents, centrist Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and reformist Mohammad Khatami, Iranian voters forcefully entered the fray to support Rouhani’s key promises of “prudent” economic management, interaction with the world and a relaxation of the highly securitized political atmosphere.

The vote ensures that Rouhani will be actively involved in convincing his Western interlocutors as well as skeptics inside Iran that through diplomacy, an agreement that respects Iran’s sovereignty — as well as the Islamic Republic’s legitimacy in protecting that sovereignty — and addresses Western concerns regarding the potential weaponization of Iran’s nuclear program is possible.

It is true that Rouhani will not be the sole decision-maker and has to negotiate with Iran’s other centers of power. An agreement must also receive broad support inside Iran and could be torpedoed by domestic forces framing it as a disproportionate concession to Western “bullying”.

But the need to convince other domestic stakeholders should not be confused with Rouhani not being given room to pursue, at least for a while, a “fair” agreement that also addresses the P5+1′s concerns. The fact that Rouhani is being told by no less than Leader Ali Khamenei not to trust Western powers should be construed as Khamenei’s fall-back “I told you so” position in case of failure and not an inhibitor of the attempt to reach an agreement.

Both reformist Khatami and hardline Mahmoud Ahmadinejad were given room to negotiate with Western powers during their presidencies. An agreement during Khatami’s presidency could not be reached because of the Bush administration’s insistence on “not a single centrifuge spinning.” A potential confidence-building agreement to transfer fissile material out of Iran during Ahmadinejad’s presidency was first rejected by a whole array of political forces inside Iran who were fearful that a deal with outsiders would pave the way for domestic repression in the tumultuous post-2009 election. Later, a similar agreement was rejected by the Obama administration, which did not want to abandon the success it was having in creating a willing coalition in favor of sanctions.

And herein lies the challenge for the folks who seem to have a voracious appetite for sanctions. In voting into office a reasonable face of Iran, the Iranian electorate is also counting on an encounter with the US’ reasonable face. Demanding significant confidence-building measures from Iran in exchange for vague promises of significant steps by Western powers in the future — promises that, given Congress’ stamp on many of the sanctions in place, are unlikely to be fulfilled soon — doesn’t seem all that reasonable.

The attitude and judgment of the Iranian electorate should not be taken lightly. In the midst of a region where hope about the positive impact of an Obama presidency has all but vanished, failure to reach an agreement with the reasonable face of Iran will be perceived as yet another clueless — and dangerous — US policy of heavy-handed demands without a clear understanding of the end game and the costs for achieving it.

With the Iranian government and electorate in the same corner, at least for now, it will be much harder to describe the sanctions regime as anything but a vindictive policy of collective punishment intended to not only bring down the Iranian government, but also destabilize the lives and livelihoods of the Iranian people. An academic who regularly visits Iran recently told me he was surprised by the extent of negative attitudes towards the US even in northern Tehran — the supposed bastion of secular and “westernized Iranians”. Things have really changed in a couple of years, he said.

I am not very keen on anecdotal evidence but the observation makes sense. Moves that reject the Iranian people’s efforts to change the course of their government’s policies and instead intensify policies of collective punishment will reap what they sow.

Photo Credit: Mona Hoobehfekr

]]>by Omid Memarian

Traditionally, a few months before a presidential election in Iran, the government opens the public sphere, giving more freedom to the press, more space for activists to speak out and even loosening social restrictions like the one on women’s clothing and hijab. But less than two months before [...]]]>

by Omid Memarian

Traditionally, a few months before a presidential election in Iran, the government opens the public sphere, giving more freedom to the press, more space for activists to speak out and even loosening social restrictions like the one on women’s clothing and hijab. But less than two months before Iran’s June 14 election, the situation feels very different in Tehran. In fact, the opposite is happening.

In mid-January, Iranian intelligence forces arrested more than 16 journalists and questioned many more. All of them were released after a few weeks. Iranian intelligence also summoned the managing editors of major publications and warned them against criticizing the government during the election season.

A number of political activists linked to the reformists’ camp, including former MP Hossein Loghmanian, have also been arrested in the last few weeks. And just months before the election, instead of experiencing more freedom, three major publications — Mehrnameh, Aseman and Panjareh — have shut down voluntarily to avoid likely censure and official closure. A reporter from one of these publications told me, “We all thought we were going to have a similar environment like in the past, and that the government would be more tolerant regarding the media’s performance, but the monitoring and censorship imposed by the intelligence is intensifying day by day.”

It’s not just about the media or activists anymore either. On April 30, Reuters reported that Bagher Asadi, a prominent Iranian diplomat — well-known and respected in UN diplomatic circles — had been arrested in mid-March. The government kept the arrest quiet for more than six weeks, but once the family leaked the news to the media, they confirmed it.

Former diplomat Mohammad Reza Heydari told me on Thursday that he believes the arrest occurred because Asadi was critical of Ahmadinejad’s foreign policy and challenged the government’s performance on a number of occasions — something Tehran does not tolerate, especially when it comes from Iranians.

These are just a few examples of how the Iranian government is getting ready for June. Remembering the aftermath of the 2009 presidential election, the widespread protests in the streets and the massive number of arrests, the government has chosen to preempt any possible challenge to the regime’s narrative on a wide range of issues, from the government’s policies, to the candidates’ qualifications, to the ongoing crackdown on dissidents.

By now, two presidential candidates in the last election, Mehdi Karroubi and Mir Hossein Mousavi, as well as Mousavi’s wife Zahra Rahnavard, have spent well over two years under house arrest. These two were beloved politicians in the eyes of Islamic Republic founder Ayatollah Khomeini. Even so, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei can’t tolerate them. Meanwhile, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, whom Khamenei supported unconditionally in his first term, now won’t pass up any opportunity to criticize the establishment.

So if the regime can’t trust a former prime minister and a former head of parliament, or even it’s current president, then whom can they, or rather, the Supreme Leader, trust? The answer is basically no one. And if you don’t trust anyone, from veteran revolutionaries to the younger generation of political figures, then what do you do with a presidential election?

The regime’s extreme sense of suspicion and distrust, and the level of squabbling amongst the political parties, who, regardless of ideology or revolutionary ideals, are all greedy for a piece of the pie, point to an unsettling future for Iran’s political sphere in the months to come. The Supreme Leader will do whatever it takes to make sure one of his loyalists ends up in office.

As Khamenei strives to keep his stranglehold on power, we should expect intensifying censorship and control over the media, civil society and political activists in the coming months. No matter who is nominated for Iran’s presidential election in the coming days, the regime is ready to avoid any surprises, regardless of the cost.

]]>via IPS News

A review of Flynt Leverett and Hillary Mann Leverett’s “Going to Tehran: Why the United States Must Come to Terms with the Islamic Republic of Iran” (Metropolitan Books, 2013)

“Going to Tehran” arguably represents the most important work on the subject of U.S.-Iran relations to be published thus [...]]]>

via IPS News

A review of Flynt Leverett and Hillary Mann Leverett’s “Going to Tehran: Why the United States Must Come to Terms with the Islamic Republic of Iran” (Metropolitan Books, 2013)

“Going to Tehran” arguably represents the most important work on the subject of U.S.-Iran relations to be published thus far.

Flynt Leverett and Hillary Mann Leverett tackle not only U.S. policy toward Iran but the broader context of Middle East policy with a systematic analytical perspective informed by personal experience, as well as very extensive documentation.

More importantly, however, their exposé required a degree of courage that may be unparalleled in the writing of former U.S. national security officials about issues on which they worked. They have chosen not just to criticise U.S. policy toward Iran but to analyse that policy as a problem of U.S. hegemony.

Both wrote memoranda in 2003 urging the George W. Bush administration to take the Iranian “roadmap” proposal for bilateral negotiations seriously but found policymakers either uninterested or powerless to influence the decision. Hillary Mann Leverett even has a connection with the powerful American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), having interned with that lobby group as a youth.

After leaving the U.S. government in disagreement with U.S. policy toward Iran, the Leveretts did not follow the normal pattern of settling into the jobs where they would support the broad outlines of the U.S. role in world politics in return for comfortable incomes and continued access to power.

Instead, they have chosen to take a firm stand in opposition to U.S. policy toward Iran, criticising the policy of the Barack Obama administration as far more aggressive than is generally recognised. They went even farther, however, contesting the consensus view in Washington among policy wonks, news media and Iran human rights activists that President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s election in June 2009 was fraudulent.

The Leveretts’ uncompromising posture toward the policymaking system and those outside the government who support U.S. policy has made them extremely unpopular in Washington foreign policy elite circles. After talking to some of their antagonists, The New Republic even passed on the rumor that the Leveretts had become shills for oil companies and others who wanted to do business with Iran.

The problem for the establishment, however, is that they turned out to be immune to the blandishments that normally keep former officials either safely supportive or quiet on national security issues that call for heated debate.

In “Going to Tehran”, the Leveretts elaborate on the contrarian analysis they have been making on their blog (formerly “The Race for Iran” and now “Going to Tehran”) They take to task those supporting U.S. systematic pressures on Iran for substituting wishful thinking that most Iranians long for secular democracy, and offer a hard analysis of the history of the Iranian revolution.

In an analysis of the roots of the legitimacy of the Islamic regime, they point to evidence that the single most important factor that swept the Khomeini movement into power in 1979 was “the Shah’s indifference to the religious sensibilities of Iranians”. That point, which conflicts with just about everything that has appeared in the mass media on Iran for decades, certainly has far-reaching analytical significance.

The Leveretts’ 56-page review of the evidence regarding the legitimacy of the 2009 election emphasises polls done by U.S.-based Terror Free Tomorrow and World Public Opinon and Canadian-based Globe Scan and 10 surveys by the University of Tehran. All of the polls were consistent with one another and with official election data on both a wide margin of victory by Ahmadinejad and turnout rates.

The Leveretts also point out that the leading opposition candidate, Hossein Mir Mousavi, did not produce “a single one of his 40,676 observers to claim that the count at his or her station had been incorrect, and none came forward independently”.

“Going to Tehran” has chapters analysing Iran’s “Grand Strategy” and on the role of negotiating with the United States that debunk much of which passes for expert opinion in Washington’s think tank world. They view Iran’s nuclear programme as aimed at achieving the same status as Japan, Canada and other “threshold nuclear states” which have the capability to become nuclear powers but forego that option.

The Leveretts also point out that it is a status that is not forbidden by the nuclear non-proliferation treaty – much to the chagrin of the United States and its anti-Iran allies.

In a later chapter, they allude briefly to what is surely the best-kept secret about the Iranian nuclear programme and Iranian foreign policy: the Iranian leadership’s calculation that the enrichment programme is the only incentive the United States has to reach a strategic accommodation with Tehran. That one fact helps to explain most of the twists and turns in Iran’s nuclear programme and its nuclear diplomacy over the past decade.

One of the propaganda themes most popular inside the Washington beltway is that the Islamic regime in Iran cannot negotiate seriously with the United States because the survival of the regime depends on hostility toward the United States.

The Leveretts debunk that notion by detailing a series of episodes beginning with President Hashemi Rafsanjani’s effort to improve relations in 1991 and again in 1995 and Iran’s offer to cooperate against Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan and, more generally after 9/11, about which Hillary Mann Leverett had personal experience.

Finally, they provide the most detailed analysis available on the 2003 Iranian proposal for a “roadmap” for negotiations with the United States, which the Bush administration gave the back of its hand.

The central message of “Going to Tehran” is that the United States has been unwilling to let go of the demand for Iran’s subordination to dominant U.S. power in the region. The Leveretts identify the decisive turning point in the U.S. “quest for dominance in the Middle East” as the collapse of the Soviet Union, which they say “liberated the United States from balance of power constraints”.

They cite the recollection of senior advisers to Secretary of State James Baker that the George H. W. Bush administration considered engagement with Iran as part of a post-Gulf War strategy but decided in the aftermath of the Soviet adversary’s disappearance that “it didn’t need to”.

Subsequent U.S. policy in the region, including what former national security adviser Bent Scowcroft called “the nutty idea” of “dual containment” of Iraq and Iran, they argue, has flowed from the new incentive for Washington to maintain and enhance its dominance in the Middle East.

The authors offer a succinct analysis of the Clinton administration’s regional and Iran policies as precursors to Bush’s Iraq War and Iran regime change policy. Their account suggests that the role of Republican neoconservatives in those policies should not be exaggerated, and that more fundamental political-institutional interests were already pushing the U.S. national security state in that direction before 2001.

They analyse the Bush administration’s flirtation with regime change and the Obama administration’s less-than-half-hearted diplomatic engagement with Iran as both motivated by a refusal to budge from a stance of maintaining the status quo of U.S.-Israeli hegemony.

Consistent with but going beyond the Leveretts’ analysis is the Bush conviction that the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq had shaken the Iranians, and that there was no need to make the slightest concession to the regime. The Obama administration has apparently fallen into the same conceptual trap, believing that the United States and its allies have Iran by the throat because of its “crippling sanctions”.

Thanks to the Leveretts, opponents of U.S. policies of domination and intervention in the Middle East have a new and rich source of analysis to argue against those policies more effectively.

*Gareth Porter, an investigative historian and journalist specialising in U.S. national security policy, received the UK-based Gellhorn Prize for journalism for 2011 for articles on the U.S. war in Afghanistan.

Photo: Tehran skyline in Iran.

]]>