by Hooshang Amirahmadi

President Barack Obama’s move towards normalization of relations with Cuba has generated lots of hope and analyses that a similar development may take place with Iran. Jim Lobe, founder of the Lobe Log and Washington Bureau Chief of the Inter Press Service, is one such observer. His recent article offers an excellent elaboration of the arguments. I rarely comment on writings by others, but his article deserves a response.

Lobe writes, “In my opinion, Obama’s willingness to make a bold foreign policy move [on Cuba] should—contrary to the narratives put out by the neoconservatives and other hawks—actually strengthen the Rouhani-Zarif faction within the Iran leadership who are no doubt arguing that Obama is serious both about reaching an agreement and forging a new relationship with the Islamic Republic.”

As someone who has spent 25 years trying to mend relations between the US and Iran, I wish Mr. Lobe and his liberal allies were right, and that their “neoconservative” opponents were wrong in their assessments that after Cuba comes Iran; unfortunately they are not. The truth is that Obama cannot so easily unlock the 35-year US-Iran entanglement that involves complex forces, including an Islamic Revolution.

First, Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif and President Hassan Rouhani used to tell Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei that Obama could be trusted, but after 14 months and many rounds of negotiations, they have now subscribed to Khamenei’s line that the US cannot be trusted. Iran’s nuclear program has already been reduced to a symbolic existence but the promised relief from key sanctions, Rouhani’s main incentive to negotiate, is nowhere on the horizon.

During the meeting in Oman between Kerry and Zarif just before the November 24, 2014 deadline for reaching a “comprehensive” deal, as disclosed by the parliamentarian Mohammad Nabavian in an interview, “[Secretary of State] Kerry crossed all Iranian red lines” and Zarif left for Tehran “thinking that the negotiations should stop.” One such red line concerns Iran’s missile program, which is now included in the negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program.

In a recent letter to his counterparts throughout the world regarding the talks and why a comprehensive deal was not struck last November, Zarif writes that “demands from the Western countries [i.e., the US] are humiliating and illegitimate” and that the “ball is now in their court.” Partly reflecting this disappointment, the Rouhani Government has increased Iran’s defense and intelligence budgets for 2015 by 33 percent and 48 percent respectively (the Iranian calendar begins on March 21).

Second, Zarif and Rouhani could not make the “beyond-the-NPT” concessions that they have made if the supreme leader had not authorized them. The argument that Khamenei and his “hardline” supporters are the obstacle misses the fact that while they have raised “concern” about Iran’s mostly unilateral concessions and the US’s “rapacious” demands, they (particularly the supreme leader) have consistently backed the negotiations and the Iranian negotiators.

Third, Lobe’s thinking suggests that the problem between the two governments is a discursive and personal one: if Khamenei is convinced that Obama is a honest man, then a nuclear agreement would be concluded and a new relationship would be forged between the two countries. What this genus of thinking misses is a radical “Islamic Revolution” and its “divine” Nizam (regime) that stands between Washington and Tehran.

The Islamic Revolution has been anti-American from its inception in 1979 (and not just in Iran), and will remain so as long as the first generation revolutionary leaders rule. The US has also been hostile to the theocratic regime and has often tried to change it. No wonder Khamenei and his people view the US as an “existential threat,” and to fend it off, they have built a “strategic depth” extending to Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Yemen and other countries.

Fourth, several times in the past the Iran watchers in the West have become excited about elections that have produced “moderate” governments, making them naively optimistic that a change in relations between the US and Iran would follow. What they miss is that the Islamic “regime” (nizam) and the Islamic “government” are two distinct entities, with the latter totally subordinated to the former.

Specifically, the Nizam (where the House of Leader and revolutionary institutions reside) is ideological and revolutionary, whereas the government has often been pragmatic. Indeed, in the last 35 years, the so-called hardliners have controlled the executive branch for less than 10 years. The division of labor should be easy to understand: the Nizam guards the divine Islamic Revolution against any deviation and intrusion while the government deals with earthly butter and bread matters.

Fifth, to avoid a losing military clash with the US and at the same time reduce Washington’s ability to change its regime or “liberalize” it, the Islamic Republic has charted a smart policy towards the US: “no-war, no-peace.” The US has also followed a similar policy towards Iran to calm both anti-war and anti-peace forces in the conflict. Thus, for over 35 years, US-Iran relations have frequently swung between heightened hostility and qualified moderation (in Khamenei’s words, “heroic flexibility”).

Sixth, the Cuban and Iranian cases are fundamentally dissimilar. True, the Castros were also anti-American and are first-generation leaders, but Fidel is retired and on his deathbed while his brother Raul has hardly been as revolutionary as Fidel. Besides, with regard to US-Cuban normalization, Fidel and his brother can claim more victory than Obama; after all, the Castros did not cave in, Obama did. Furthermore, the Castros are their own bosses, head a dying socialist regime, and are the judges of their own “legacy.”

In sharp contrast, Khamenei subscribes to a rising Islam, heads a living though conflicted theocracy, and subsists in the shadow of the late Ayatollah Khomeini who called the US a “wolf” and Iran a “sheep,” decreeing that they cannot coexist. Indeed, in the Cuban case, the US held the tough line while in the case of Iran, the refusal to reconcile is mutual. Furthermore, the Cuban lobby is a passing force and no longer a match for the world-wide support that the Cuban government garners. Conversely, in the Iranian case, Obama has to deal with powerful Israeli and Arab lobbies, and the Islamic Republic does not have effective international support.

On the other hand, we also have certain similarities between the Cuban and Iranian cases. For example, both revolutions have been subject to harsh US sanctions and other forms of coercion that Obama called a “failed approach.” Obama is also in his second term, free from the yoke of domestic politics, and wishes to build a lasting legacy. Despite these similarities, the differences between the Iranian Islamic regime and the Cuban socialist system make the former a tougher challenge for Obama to solve.

Finally, while I do not think that the Cuban course will be followed for Iran any time soon, I do think that certain developments are generating the imperative for an US-Iran reconciliation in the near future. On Iran’s side, they include a crippled economy facing declining oil prices, a young Iranian population demanding transformative changes, and the gradual shrinking of the first-generation Islamic revolutionary leaders.

On the US side, the changes include an imperial power increasingly reluctant to use force, rising Islamic extremism, growing instability in the Persian Gulf and the larger Middle East, and the difficulty of sustaining the “no-war, no-peace” status quo in the absence of a “comprehensive” deal on Iran’s nuclear program. However, on this last issue, in Washington and Tehran, pessimism now far outweighs optimism, a rather sad development. Let us hope that sanity will prevail.

Photo: Iranian President Hassan Rouhani greets a rally in commemoration of the Islamic Republic’s 35 anniversary of its 1979 revolution in Tehran, Iran on Feb. 11, 2014. Credit: ISNA/Hamid Forootan

]]>by Robert E. Hunter

It’s too early to tell all there is to be told about the negotiations in Vienna between the so-called P5+1 and Iran on the latter’s nuclear program. The “telling” by each and every participant of what happened will surely take place in the next several days, and then better-informed assessments can be made. As of now, we know that the talks did not reach agreement by the November 24 deadline—a year after the interim Joint Plan of Action was agreed—and that the negotiators are aiming for a political agreement no later than next March and a comprehensive deal by June 30.

This is better than having the talks collapse. Better still would have been a provisional interim fill-in-the-blanks memorandum of headings of agreement that is so often put out in international diplomacy when negotiations hit a roadblock but neither side would have its interests served by declaring failure.

An example of failing either to set a new deadline or to issue a “fill in the blanks” agreement was vividly provided by President Bill Clinton’s declaration at the end of the abortive Camp David talks in December 2000. He simply declared the talks on an Israeli-Palestinian settlement as having broken down, rather than saying: progress has been made, here are areas of agreement, here is the timetable for the talks to continue, blah, blah. I was at dinner in Tel Aviv with a group of other American Middle East specialists and Israel’s elder statesman, Shimon Peres, when the news came through. We were all nonplussed that Clinton had not followed the tried and true method of pushing off hard issues until talks would be resumed, at some level, at a “date certain,” which had been the custom on this diplomacy since at least 1981. One result was such disappointment among Palestinians that the second intifada erupted, producing great suffering on all sides and a setback for whatever prospects for peace existed. Poor diplomacy had a tragic outcome.

This example calls for a comparison of today’s circumstances with past diplomatic negotiations of high importance and struggles over difficult issues. Each, it should be understood, is unique, but there are some common factors.

Optimism

The first is the good news that I have already presented: the talks in Vienna did not “break down” and no one walked away from the table in a huff. The other good news is that the official representatives of the two most important negotiators, the United States and Iran, clearly want to reach an agreement that will meet both of their legitimate security, economic, and other interests. Left to themselves, they would probably have had a deal signed, sealed, and delivered this past weekend if not before. But they have not been “left to themselves,” nor will they be, as I will discuss below.

Further good news is that all the issues involving Iran’s nuclear program have now been so masticated by all the parties that they are virtually pulp. If anything is still hidden, it is hard to imagine, other than in the minds of conspiracy theorists who, alas, exist in abundance on any issue involving the Middle East. A deal to be cut on specifics? Yes. New factors to consider? Highly unlikely.

Even more good news is that the United States and the other P5+1 countries (US, UK, Russia, China, France plus Germany), have got to know much better than before their official Iranian counterparts and overall Iranian interests, perspectives, and thinking (US officials, long chary of being seen in the same room with “an Iranian,” lag behind the others in this regard). We can hope that this learning process has also taken place on the Iranian side. This does not mean that the actual means whereby Iran takes decisions—nominally, at least, in the hands of the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei—is any less opaque. But even so, there is surely greater understanding of one another—one of the key objectives of just about any diplomatic process.

A partial precedent can be found in US-Soviet arms control and other negotiations during the Cold War. The details of these negotiations were important, or so both sides believed, especially what had to be a primarily symbolic fixation with the numbers of missile launchers and “throw-weight.” This highly charged political preoccupation took place even though the utter destruction of both sides would be guaranteed in a nuclear war. Yet even with great disparities in these numbers, neither side would have been prepared to risk moving even closer to the brink of conflict. Both US and Soviet leaders came to realize that the most important benefit of the talks was the talking, and that they had to improve their political relationship or risk major if not catastrophic loss on both sides. The simple act of talking proved to be a major factor in the eventual end of the Cold War.

The parallel with the Iran talks is that the process itself—including the fact that it is now legitimate to talk with the “Devil” on the other side—has permitted, even if tacitly, greater understanding that the West and Iran have, in contrast to their differences, at least some complementary if not common interests. For the US and Iran, these include freedom of shipping through the Strait of Hormuz; counter-piracy; opposition to Islamic State (ISIS or IS); stability in Afghanistan; opposition to the drug trade, al-Qaeda, Taliban and terrorism; and at least a modus vivendi in regard to Iraq. This does not mean that the US and Iran will see eye-to-eye on all of these issues, but they do constitute a significant agenda, against which the fine details of getting a perfect nuclear agreement (from each side’s perspective) must be measured.

Pessimism

There is also bad news, however, including in the precedents, or partial precedents, of other negotiations. As already noted, negotiations over the fate of the West Bank and Gaza have been going on since May 1979 (I was the White House member of the first US negotiating team), and, while some progress has been made, the issues today look remarkably like they did 37 years ago.

Negotiations following the 1953 armistice in the Korean War have also been going on, with fits and starts, for 61 years. The negotiations over the Vietnam War (the US phase of it) dragged on for years and involved even what in retrospect seem to have been idiocies like arguments over the “shape of the table.” They came to a conclusion only when the US decided it was time to get out—i.e., the North Vietnamese successfully waited us out. Negotiations over Kashmir have also been going on, intermittently, since the 1947 partition of India. The OSCE-led talks on Nagorno-Karabakh (Armenia versus Azerbaijan) have gone on for about two decades, under the nominal chairmanship of France, Russia, and the United States. All this diplomatic activity relates to a small group of what are now called “frozen conflicts,” where negotiations go on ad infinitum but without a lot of further harm done.

But with the exception of the Vietnam talks, all the other dragged-out talking has taken place against the background of relatively stable situations. Talks on Korea go nowhere, but fighting only takes place in small bursts and is not significant. Even regarding the Palestinians, fighting takes place from time to time, including major fighting, but failure to get a permanent end of hostilities does not lead to a fundamental breakdown of “stability” in the Middle East, due to the tacit agreement of all outside powers.

Dangers of Delay

The talks on the Iranian nuclear program, due to restart in December, are different. While they are dragging along, things happen. Sanctions continue and could even be increased on Iran, especially with so many “out for blood” members of the incoming 114th US Congress. Whether this added pressure will get the US a better deal is debatable, but further suffering for the Iranian people, already far out of proportion to anything bad that Iran has done, will just get worse. Iran may also choose to press forward with uranium enrichment, making a later deal somewhat—who knows how much—more difficult to conclude and verify. Israel will have calculations of its own to make about what Iran is up to and whether it should seriously consider the use of force. And chances for US-Iranian cooperation against IS will diminish.

So time is not on the side of an agreement, and any prospects of Iranian-Western cooperation on other serious regional matters have been further put off—a high cost for all concerned.

Due to the contentious domestic politics on both sides, the risks are even greater. In Iran, there are already pressures from the clerical right and from some other nationalists to undercut both the Iranian president, Hassan Rouhani, and the lead negotiator, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, both of whom, in these people’s eyes, are now tainted. We can expect further pressures against a deal from this quarter.

The matter is at least as bad and probably worse on the Western side—more particularly, on the US side. The new Congress has already been mentioned. But one reason for consideration of that factor is that, on the P5+1 side of the table, there have not just been six countries but eight, two invisible but very much present, and they are second and third in importance at the table only behind the US itself: Israel and Saudi Arabia.

Both countries are determined to prevent any realistic agreement with Iran on its nuclear program, even if declared by President Barack Obama, in his judgment, to satisfy fully the security interests of both the United States and its allies and partners, including Israel and the Gulf Arabs. For them, in fact, the issue is not just about Iran’s nuclear program, but also about the very idea of Iran being readmitted into international society. For the Sunni Arabs, it is partly about the struggle with the region’s Shi’as, including in President Bashar Assad’s Syria but most particularly in Iran. And for all of these players, there is also a critical geopolitical competition, including vying for US friendship while opposing Iran’s reemergence as another regional player.

The United States does not share any of these interests regarding Sunni vs. Shi’a or geopolitical competitions among regional countries. Our interests are to foster stability in the region, promote security, including against any further proliferation of nuclear weapons (beginning with Iran), and to help counter the virus of Islamist fundamentalism. On the last-named, unfortunately, the US still does not get the cooperation it needs, especially from Saudi Arabia, whose citizens have played such an instrumental role in exporting the ideas, money, and arms that sustain IS.

Thus it is to be deeply regretted, certainly by all the governments formally represented in the P5+1, that efforts to conclude the talks have been put off. The enemies of agreement, on both sides, have gained time to continue their efforts to prevent an agreement—enemies both in Iran and especially in the United States, with the heavy pressures from the Arab oil lobby and the Israeli lobby in the US Congress.

What happens now in Iran can only be determined by the Iranians. What happens with the P5+1 will depend, more than anything else, on the willingness and political courage of President Obama to persevere and say “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead” to the Gulf Arab states, Israel, and their allies in the United States, and do what he is paid to do: promote the interests and security of the United States of America.

]]>by Peter Jenkins

Seyed Hossein Mousavian, the lead author of Iran and the United States: An Insider’s View on the Failed Past and the Road to Peace, has two objectives: to help American readers understand the Iranian perspective on the fraught US-Iranian relationship, and to advocate a sustained attempt to break the cycle of hostility that was triggered by the 1979 Islamic revolution.

Such is the suspicion on both sides of this relationship that some readers may wonder about the extent to which Mousavian’s descriptions of the Iranian perspective can be trusted. This reviewer’s opinion is that Mousavian—a former Iranian ambassador who has been living in the US since 2009—whom the reviewer has known since 2004, is not trying to pull wool over anyone’s eyes. There is corroborating evidence for much of the information he advances. If in places the reader senses that he or she is not getting the full story, a respectable explanation is to hand: those who have worked at the heart of a government, as Mousavian has done, are bound to be “economical” with certain truths, as a British cabinet secretary once put it.

The Iranian political establishment can be reduced, simplistically, to two broad currents. The first contains those who nurture so great a sense of grievance towards the US, and so deep a mistrust, that they have no wish to end the intermittent cold war of the last 35 years. In the second current are those who understand that nurturing grievances is futile, who recognise that the US has legitimate grievances of its own, and who believe that a measure of détente is in the interest of both countries.

Mousavian belongs to the second current. So do Iran’s president since August 2013, Hassan Rouhani, and his foreign minister and chief nuclear negotiator, Mohammed Javad Zarif. Iran’s ultimate decision-maker and religious leader, Ayatollah Seyed Ali Khamenei, straddles the two camps. He is deeply distrustful of the United States, which he suspects of being bent on the overthrow of the Islamic Republic and of having no interest in détente, but he is ready to give the second current opportunities to prove him wrong.

Iran’s president from 2005-13, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad—who created a deplorable impression in the West, and gifted Israeli propagandists, by denying the reality of the Holocaust—came to office as a member of the first current, a “hard-liner.” But one of the revelations of this book is that he made more attempts than any previous leader to engineer a thaw in relations with the United States.

Mousavian’s intriguing thesis is that Ahmadinejad believed that achieving détente would be so popular with Iranian voters that it would help him to become Iran’s equivalent of Vladimir Putin.

Amb. Mousavian was the spokesman for Iran in the negotiations over its nuclear program with the international community 2003-05.

The middle section of the book is given over to an account of the US-Iranian relationship from the author’s first-hand experience. Mousavian does not flinch from addressing all the episodes that have generated a sense of grievance on one side or the other, from cataloguing the false starts and missed opportunities, or from exploring the incidents that have set back relations just when an improvement seemed to be in the offing.

He has been so well connected to several leaders of Iran’s nezam (establishment) during most of the last 35 years that these chapters amount to a fascinating story, told from the inside of a political system that many foreigners find opaque.

It is somewhat remarkable how often relations have been set back just when it seemed that a thaw was about to set in. In 1992, intelligence about Iranian nuclear purchases undermined the good will created by Iran’s intercessions to secure the release of US hostages in the Lebanon. In 1996, the Kolahdooz incident set back relations with Europe that had been improving since the early 90s. In 2002, the Karine A incident negated the cooperation that the US had been receiving from Iran since 9/11, and it led to the infamous naming of Iran as a member of the “Axis of Evil” in a State of the Union address.

Mousavian suspects that these and other setbacks were not coincidental; they were the work of people who had no interest in a thaw. That theory would account for the haste with which Iran’s enemies have asserted Iranian responsibility for such incidents. But in the last analysis, answers to these puzzles of responsibility have yet to be authenticated.

In any case, how realistic is it to suppose that an improvement in US-Iran relations can be achieved?

Mousavian admits that there are formidable obstacles to a full normalisation, and he seems to doubt that the US and Iran will become best buddies any time soon.

Chief among the obstacles, seen from the US side, are Iran’s refusal to modify its view that the Jewish character of the Israeli state, proclaimed in Israel’s constitution, is bound to result in injustice, oppression and humiliation for Palestinians living in Israel, and has in fact done so—plus Iran’s determination to support a fellow-Shia movement that Israel and the US deem to be terrorist, Hezbollah.

On the Iranian side, Ayatollah Khamenei fears the consequences of anything more than a modest rapprochement. In his view, the opening of a US embassy in Tehran, for instance, would create opportunities for US subversion of the Islamic Republic; and greater exposure of the Iranian population to all things American would undermine respect for Islamic values. He remains convinced that the US seeks the overthrow of the Islamic Republic.

Yet Mousavian believes that there is a middle ground between mutual hostility and full normalisation. He sees scope for the US and Iran to work together, on a basis of mutual respect, to achieve common objectives in areas where their interests coincide. At present those areas include Afghanistan, counter-narcotics, WMD counter-proliferation, energy security, and combating the Jihadi threat in Iraq and Syria.

Developing what Mousavian terms “a framework for cooperation” should be accompanied, he suggests, by an agreement to lock the drawer that contains both sides’ equally long lists of historic grievances, and by a commitment to eschew the rhetoric of enmity and aggression.

The key to taking relations on to a new plane, he argues, is resolving the dispute over Iran’s nuclear activities. This dispute has been fuelled by Israel, partly perhaps for Palestine-related reasons, and by the US’ strategic balance of power considerations.

He believes that a resolution is nonetheless possible. The progress made by American and Iranian negotiators since September 2013, and the alarm that this has caused Israel’s prime minister, suggests that he is right.

Mousavian warns his readers against pressing Iran to cut back its uranium enrichment capacity from the current level, which, objectively, is modest and cannot reasonably be construed as threatening as long as its use is monitored by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). He fears that the US and EU negotiators will fail to appreciate the cultural and psychological factors that would lead the Iranian nezam to prefer no deal to the kind of capacity reductions that the US and EU have been seeking.

The Islamic Republic is rooted in nationalist as much as in religious values, he explains. The nezam is quick to perceive threats to Iran’s sovereignty and national dignity. They would rather defy than be humiliated. They are ready to engage in reasonable compromise but they will not capitulate.

It is these insights into the Islamic Iranian mind-set that are likely to make this book exceptionally interesting for all but students of Iran—and even they may like to compare their views with those of Mousavian.

He will doubtless be pleased if the book sells well, as it deserves to do. But what will please him most, I suspect, is if it contributes to a better understanding of Iran in the US and in Europe, and if it helps bring to a close a quarrel that reflects well on neither side.

]]>by Adnan Tabatabai

The negotiations in Vienna between world powers and Iran over its nuclear program are in the home stretch even if the July 20 deadline to reach a final deal set by last year’s interim accord will not be met.

Few expected a deal to be reached so quickly, less than [...]]]>

by Adnan Tabatabai

The negotiations in Vienna between world powers and Iran over its nuclear program are in the home stretch even if the July 20 deadline to reach a final deal set by last year’s interim accord will not be met.

Few expected a deal to be reached so quickly, less than one year after last year’s historic agreement, the Joint Plan of Action. Experts argued early on that there would be an extension. Even Iran’s Deputy Foreign Minister Seyyed Abbas Araqchi said on July 12 that “there is a possibility of extending the talks for a few days or a few weeks if progress is made.”

While the possibility of a final deal being reached any time soon is far from guaranteed, one thing is certain: the Rouhani government’s most important task will be effectively framing the outcome of these talks at home.

Zarif Makes Iran’s Case

Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif and his team made two significant moves in presenting Iran’s position more clearly than ever before during this marathon round of talks, which began on July 2.

First, Zarif offered details, for the first time, about Iran’s proposal in an interview with the New York Times.

Second, Zarif’s team published a document clearly outlining Iran’s view of its practical needs for its nuclear program in English, which it distributed through social media.

Prior to this latest round of talks, Zarif also again emphasized his country’s willingness to reach a comprehensive agreement with world powers in a video message released by the Foreign Ministry.

This commitment is based on a number of domestic incentives.

In order to gain more strength in his critical second year in office, President Hassan Rouhani needs a policy success story. Solving the conflict over Iran’s nuclear program was among his top campaign promises, and so far he has yet to achieve any of them.

A nuclear deal would embolden him to push for ambitious policy decisions to pursue his other campaign promises.

Rouhani — to use his own words — has to “break” the devastating sanctions imposed on Iran before any meaningful economic reconstruction and development can be implemented.

With a nuclear deal in his pocket, Rouhani could begin to counter Iranian hard-liners’ and conservatives’ deep-rooted scepticism towards the West. Indeed, a nuclear deal would fly in the face of those who argue that the West cannot be trusted. Rouhani could prove that moderation and reconciliation, when strategically applied, can be extremely beneficial.

A no-deal scenario, one could therefore conclude, would considerably weaken Rouhani while strengthening his opponents at home. But this train of thought is highly simplistic.

Framing the Outcome

Regardless of what these negotiations lead to, more than half the battle will involve controlling how the outcome is framed and perceived at home.

Rouhani and Zarif will have to respond to two forms of criticism: factual and ideological.

The factual criticism will be concerned with the actual details of the negotiations — particularly those determining the scope and future prospects of Iran’s nuclear program.

The ideological criticism will be related to Zarif’s negotiating strategy. For Iran’s far-right principlist faction, Zarif’s reconciliatory approach toward world powers is not in line with Iran’s revolutionary ideals.

Many of them former supporters of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, these parliamentarians and archconservative clerics prefer a more confrontational foreign policy approach through which Iran maintains its position of resistance, is the main regional powerhouse and pursues its nuclear program without seeking approval from the international community.

The latter dimension was stressed in a follow-up meeting of the “We’re concerned” conference in Tehran, which I discussed in May. The very same figures who launched the first event gathered again in a “Red lines” session July 15 to set clear limits on what is and is not negotiable.

In many ways, these hard-liners resemble hawks in the US Congress. Both groups are trying hard to impose themselves into the negotiating process and express their discontent at being side-lined through emphatic opposition to reconciliation and prospects for normalized relations.

In fact, deal or no deal, Rouhani and Zarif will have to convince critics at home that they safeguarded Iran’s national interests — especially in terms of scientific progress and security — and maintained Iran’s position as an important regional actor.

Successfully framing the post-negotiations environment will mean that neither Rouhani nor Zarif will be able to maintain their considerable political capital even in a no-deal scenario.

A “Win-Win” for the Supreme Leader

Rouhani and Zarif have not only proven themselves as adept negotiators (Rouhani was Iran’s chief negotiator from 2003-05), they have also been skilfully manoeuvring Iran’s domestic political scene in the following ways:

- They know how to address criticism. Be it in media appearances, public speeches or during parliamentary questioning sessions, both of these men have demonstrated the perfect mix of responding to some concerns while strongly making their own cases. They have not allowed their critics to intimidate them.

- Whenever criticism has taken over, influential actors including former Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Velayati, Parliament Speaker Ali Larijani, or Chief of staff of the Armed Forces, General Hassan Firouzabadi threw their political weight behind Rouhani and his foreign minister. This was only possible through Rouhani’s connections with various political factions prior to his presidential election and his approach to the presidency thus far. These key figures’ public approval of Zarif’s negotiating strategy has often been voiced with reference to the words of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

- Iran’s foreign minister has become one of the most popular politicians in Iran. Allowing him to go alone into the firing line of hard-line criticism — especially in the case of a no-deal scenario — could be too costly for the overall political atmosphere The Supreme Leader has therefore not allowed Zarif or Rouhani to be openly criticized too harshly.

- Finally, and most importantly, even in the case of a no-deal scenario, the Supreme Leader may, in the end, achieve one major goal: proving to the Iranian public that the P5+1 (US, UK, France, China, and Russia plus Germany) stood in the way of a final agreement, and not him. While he has thus far supported Iran’s negotiating team, he has consistently decried the other side’s sincerity, which enables him to be right, deal or no deal.

“Khamenei’s personal win-win,” as a Tehran-based political analyst recently told me, would also eliminate a lot of pressure from the Supreme Leader’s shoulders, which — as the past 25 years have shown — has always led to less domestic turmoil.

Indeed, when under pressure, Supreme Leader Khamenei approves tighter security measures. Not only was this the case during the 2009 post-election crisis when crackdowns on protests and the arrests of prominent critics escalated, but also during the final year of the Ahmadinejad presidency when some of his aides were verbally and, in the case of Ali Akbar Javanfekr, even physically attacked.

Thus, Iran’s negotiating partners should keep in mind that while Zarif’s negotiating team is committed to achieving a comprehensive agreement, and Rouhani would gain considerable political clout in the event of one, it would be wrong to operate on the assumption that they are desperate for it. Their careers do not depend on the outcome of the talks.

]]>by Jasmin Ramsey

The only certainty now about the talks between world powers and Iran over its nuclear program is that the negotiators have their work cut out for them. Other than occasional runaway comments to the press from France, and now China, the parties have remained tight-lipped about their [...]]]>

by Jasmin Ramsey

The only certainty now about the talks between world powers and Iran over its nuclear program is that the negotiators have their work cut out for them. Other than occasional runaway comments to the press from France, and now China, the parties have remained tight-lipped about their closed-door dealings. However, judging by the tone of the briefings by the US and Iran coming out of the 5-day session that ended in Vienna last Friday, the pressure has increased as the self-imposed deadline looms. The negotiations can certainly be extended, but as a senior US official noted in a background briefing to the press:

We are all focused on reaching July 20th. As I’ve said before, if we get close and we need a few more days, I don’t think anyone will mind. But we are very focused on getting it done now. We have all agreed that time is not in anyone’s interest; it won’t help get there. And if indeed by the time we get to July 20th we are still very far apart, then I think we will all have to evaluate what that means and what is possible or not.

What are the odds of the now formally titled “Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action” being signed by Iran and the P5+1 (US, UK, France, China, and Russia plus Germany) at the end of July? Independent scholar and LobeLog contributor Farideh Farhi offered her take during a June 21 interview with Iran Review:

Two factors work in favor of the eventual resolution of the nuclear dossier and transformation of US-Iran relations from a constant state of hostility and non-communication to interaction, even if not necessarily in constructive ways at all times. One is the seriousness of the negotiations and the political will on the part of the current administrations in both countries to prevent the nuclear dossier from becoming a pretext for war or spiraling into something uncontrollable. And the second is the high cost of failure now that both sides have invested so heavily in the talks.

But there are also factors that inhibit confidence in assuming a point of no return to status quo ante. First, in both countries there are political forces that oppose any type of interaction and lessening of tensions, although at this point my take is that opponents, encouraged by regional players, have more significant institutional power in the United States than Iran. In other words, along with political power, they have extensive policy instruments – the most important of which are legally embedded in the sanctions regime – that can be relied upon to undermine or prevent political accord between the two countries.

The second factor is the unequal power relationship between the two countries, which has consistently led various US administrations to be tempted by the argument that economic, political muscle, and military threats will eventually pay off and force various administrations in Iran to give in irrespective of domestic political equations and the stances they have taken within their own political environment. Currently, this second factor is part and parcel of broader indecision or uncertainty in the US’ strategic calculus regarding whether to come to terms with Iran as a prominent regional player or continue its three decade policy of containing it and alternatively Iran’s commitment to being an independent and powerful regional actor irrespective of fears in the neighborhood.

This dynamic of one side always wanting more than the other can give and/or alternatively being unwilling or incapable of matching concessions with what the other side deems as comparable concessions has been the source of impasse in negotiations. This is not to suggest that inflexibility or lack of realism only comes from one side. During the previous administration, Iran also miscalculated in its assessment of the leverage the United States could build through its ferocious sanctions regime in the same way the United States miscalculated in its assessment of the extent to which Iran could expand its nuclear program in the face of sanctions. As such, Iran’s expectation for the sanctions regime that took years to build to be lifted quickly and permanently is as unrealistic as the US expectation for Iran’s enrichment program to be significantly scaled back.

As to the impact of Iran-US direct talks, it is still possible for the unprecedented high profile direct engagement between the two countries in and of itself to lead to some sort of transformation in the relationship irrespective of the results of nuclear talks. If indeed the two countries’ foreign ministers or even presidents can continue to pick up the phone and talk to each other over matters of common concern or for the sake of de-escalating tensions, that by itself is an important achievement of nuclear talks and its significance should not be under-estimated. But this also depends on how the potential failure of nuclear talks is managed by both sides.

Read more here.

This article was first published by LobeLog and was reprinted here with permission. Follow LobeLog on Twitter and like us on Facebook.

Photo: The Iranian nuclear negotiating team headed by Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif (center) and Deputy Foreign Ministers Abbas Araghchi (to Zarif’s right) and Majid Takht-Ravanchi.

]]>by Shervin Malekzadeh

Millions of Iranians will gather in the coming days to watch their country take on the world in something other than politics. Against the odds, against Argentina, and after a long, eight-year absence, Iran’s participation in the World Cup is a welcome break from usual state TV programming. While the people [...]]]>

by Shervin Malekzadeh

Millions of Iranians will gather in the coming days to watch their country take on the world in something other than politics. Against the odds, against Argentina, and after a long, eight-year absence, Iran’s participation in the World Cup is a welcome break from usual state TV programming. While the people of Iran ceaselessly hope for sanctions relief and a better economy, at least for now, sports will draw their interest more than their government’s wrangling with Western powers over Iran’s nuclear portfolio.

Missing out on the festivities will be the more than 1 million recent high school graduates studying for the dreaded konkoor, a yearly university entrance exam scheduled for June 26. Tucked away in their bedrooms, poorly sheltered against the frantic shouts and exhortations just outside their doors, the temptation of the World Cup could not have come at a worse time for these students. They face a cruel calculus: an entire year of preparation to take a four-hour test focusing on five subject areas — the only way to gain college admission. The cost of failure will be an entire year of waiting just to retake the test. Those students who pass, on the other hand, will have no way of knowing beforehand where they will be placed (there are no campus visits in Iran) nor whether they will be able to enroll in their preferred course of study (their ranking on the konkoor determines both).

What is not uncertain is that most of the successful test-takers will complete their university education without securing a job or an obvious career path. More than 21 percent of all young people with a college degree were unemployed according to last year’s state figures, more than double the official national average. An astounding 43 percent of college-educated women are without work. Young, overqualified, and unemployed, most of Iran’s college graduates will continue to live at home and toil away at jobs unrelated to their degrees and majors, a state of adolescent suspension that the political scientist Diane Singerman has memorably labeled, “waithood.”

It is an inconsistency that youth and the possession of a university degree have become the strongest predictors for unemployment in Iran today. The great mystery is that none of this seems to matter. Despite considerable outrage in the media and amongst the general public about the inability of Iran’s educational system to funnel graduates into the workforce, the demand for college amongst ordinary Iranians remains insatiable.

The single-minded pursuit of credentialed merit in Iran persists against dim prospects. Since 2005, the percentage of 18-24-year-olds attending college has nearly tripled, rising from just over 20 percent to the current 55 percent, a demand fueled in part by an Ahmadinejad administration determined to establish its populist bona fides through education. State planners keen on expanding the government’s reach have been met more than halfway from below, by a society obsessed with the distinction and opportunities that “getting the paper” supposedly brings. “Learn and study what you will,” writes one long time observer of Iran’s educational system, “but above all get a university degree!”

So why participate in a system in which the odds, if not the system itself, appear to be stacked against you? This question is not limited to academia. Iranians take part in all kinds of “games,” be they educational (attending college to gain employment), political (voting in presidential elections), or athletic (the World Cup), despite very low chances of success.

Indeed, almost exactly a year ago today, more than 18 million Iranians, over 70 percent of the voting age population, participated in Iran’s presidential election despite the turmoil of the 2009 election and violent suppression of the Green Movement. Though polling and anecdotal evidence showed that many Iranians believed their vote “would not matter” and that the election would be rigged, an absolute majority turned up at the ballot box in June 2013 to vote Hassan Rouhani into office, shocking even the most astute of observers and creating a “political earthquake.”

The politics of participation in Iran is not without explanation. Disappointment and fatigue with a revolution that remains wedded to large and unwieldy promises have left many people inclined to seek their advantage in the small and manageable, to get what they can from revolutionary strictures. A college degree is unlikely to produce a job, just as a vote for Hassan Rouhani will surely not lead to Jeffersonian democracy. But while both are uncertain opportunities for progress, nonparticipation guarantees failure.

Something similar is happening with Iran’s Team Melli. The national team qualified for the World Cup just days after Rouhani’s election, the celebratory crowds for which dwarfed even the widespread street celebrations following Rouhani’s presidential win. Today, every Iranian knows the chances of the national team making it to the second round, much less winning the tournament, are almost zero. That does not mean, however, that Iranians will turn off the TV when Iran plays against Lionel Messi and the formidable Argentinian team on Saturday, or that young people won’t find a way to sneak away from their books to watch the match, all in the hopes that maybe, just maybe, the odds will turn their way.

This article was first published by LobeLog and was reprinted here with permission. Follow LobeLog on Twitter and like us on Facebook

Photo: Iranian youth celebrating in northern Tehran after Team Melli qualified for the 2014 Brazil World Cup on June 18, 2013, just days after Hassan Rouhani was elected president. Credit: Kosoof

*Editor’s note: Yesterday we covered the arrest of a group of young Iranians in Tehran, who made a video to Pharrell’s hit song, “Happy.” As noted in our story, the original fan video, which received over 160,000 views on YouTube over the month it was online, has since [...]]]>

*Editor’s note: Yesterday we covered the arrest of a group of young Iranians in Tehran, who made a video to Pharrell’s hit song, “Happy.” As noted in our story, the original fan video, which received over 160,000 views on YouTube over the month it was online, has since been marked private, but reproductions have been flourishing on the Internet. As of this posting, a May 20th (two days ago) upload by Pooya Jahandar has over 721,000 hits, and counting…

by Derek Davison

Friends, who among us has not been confronted by that irritating and morally corrosive internet video that both grates on the nerves and threatens to undermine everything that is good and decent in society? Are you interested in protecting others from being exposed to this filth? I’m here to help. Here’s a step-by-step guide to keeping YouTube’s dangerous grip off our beloved Islamic Republic:

Step 1: Find an offensive video to ban

You might consider deliberately looking for something to get mad about strange, but rest assured that combing the internet for something that outrages you is a completely legitimate and highly productive use of your time.

You might consider deliberately looking for something to get mad about strange, but rest assured that combing the internet for something that outrages you is a completely legitimate and highly productive use of your time.

Now, you can’t redirect people’s outrage with just any video. Please use a discerning eye and find something that is really offensive. Like kittens — nobody likes kittens, with their little slashing claws and sharp teeth. Babies are also good — I mean, who likes babies? Or, hypothetically of course, you could find a video of pleasant-looking young people violating the long-held prohibition on men and women appearing together in an internet video and dancing to a song sung by an American who wears a funny hat. You’ll want something that’s gone a little “viral” but hasn’t blown up too much, because then you won’t be able to greatly increase awareness of the existence of the video while simultaneously trying to make sure that it never gets seen.

Step 2: Denounce the video and arrest the participants, ideally in the most public manner possible

This is simple logic. How will people know that the YouTube video they probably haven’t seen is bad and offensive unless you do something very public to let them know? Answer: they won’t. This is not good; you can’t suppress something that only a few people know about! So put somebody in uniform, a police commander maybe, on camera to denounce the video and reassure the public that anyone who films themselves in a “false utopia” will be jolted into reality by squatting naked!

This is simple logic. How will people know that the YouTube video they probably haven’t seen is bad and offensive unless you do something very public to let them know? Answer: they won’t. This is not good; you can’t suppress something that only a few people know about! So put somebody in uniform, a police commander maybe, on camera to denounce the video and reassure the public that anyone who films themselves in a “false utopia” will be jolted into reality by squatting naked!

Then, arrest everybody involved in the making of the video. This will be difficult if we’re dealing with kittens because of the scratching and biting. Babies, on the other hand, are surprisingly easy to arrest, but they are unable to go on TV and confess to, well, whatever. This is why if you can find a video of dancing young people, that’s really the way to go. Anyway, stick the arrestees on TV and pressure them into confessing to something, anything, so the people watching know that regardless of who’s president, conservative forces will always be in control.

Step 3: Let the power of modern media work for you

By now your efforts are really starting to pay off. By publicly drawing massive amounts of attention to this video that a relatively small number of people had seen before you pointed it out to them, you’ve not only managed to alert your own public to the excellent work you’re doing, but you’ve gotten the foreign press interested as well.

6 Iranians arrested for making ‘Happy’ video via @CNN http://t.co/619PdZdXnI

— OutFrontCNN (@OutFrontCNN) May 21, 2014

This is great; young people think of the news media as “square,” which means “uncool,” so if the video is being covered by the media then people will be less interested in seeing it. Maybe you’ve even inspired a bunch of people to reproduce the original video so that even if the original is taken down the copies will still be available. This is excellent news, because our people are notoriously counter-culture and will not want to watch something if it’s all over the place, so the more copies of the video there are, the less likely it will be that anyone will look at it. If you’re really lucky, a major celebrity, like the American in the funny hat if you went that route, will publicly denounce your actions, maybe even a couple of times, and this is gold!

Then free these kids..

by Marsha B. Cohen

The results of a new survey released by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), as deplorable as they are, show that Iran is the least anti-Semitic country in the Middle East.

Not that the ADL is doing anything to point this out in their just-released report entitled, Global 100: An Index of [...]]]>

by Marsha B. Cohen

The results of a new survey released by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), as deplorable as they are, show that Iran is the least anti-Semitic country in the Middle East.

Not that the ADL is doing anything to point this out in their just-released report entitled, Global 100: An Index of Anti-Semitism. This surprising fact can only be uncovered by comparing Iranian responses with those of other Middle Eastern countries.

According to the index scores of the more than 100 countries around the world included in the survey, the most anti-Semitic place on earth is the West Bank and Gaza (93%). Iraq isn’t far behind the Palestinian territories, which are, of course, under Israeli occupation. But Iran doesn’t even make it into the survey’s worldwide top 20 anti-Semitic hotspots.

The first of the eleven statements to which respondents were asked to categorize as “probably true” or “probably false” was Jews are more loyal to Israel than to [this country/to the countries they live in]. While 56% of Iranians responded in the affirmative, in other MENA countries the percentage of respondents agreeing with this assertion were significantly higher: Saudi Arabia 71%; Lebanon 72%; Oman 76%; Egypt 78% Jordan 79%; Kuwait 80%; Qatar 80%; UAE 80%; Bahrain 81%; Yemen 81%; Iraq 83%; West Bank and Gaza 83%. (It’s too bad that Israel was not among the countries surveyed. It would be interesting to know what Israelis believe on this point.)

The other indicators of anti-Semitic attitudes were:

Jews have too much power in the business world. Iran 54%; Saudi Arabia 69%; Oman 72%; Egypt 73%; UAE 74%; Lebanon 76%; Qatar 75%; Bahrain 78%; Jordan 79%; Kuwait 79%; Yemen 82%; Iraq 84%; West Bank and Gaza 91%.

Jews have too much power in international financial markets. Iran 62%; Oman 68%; Egypt 69%; Saudi Arabia 69%; UAE 71%; Qatar 71%; Jordan 76%; Bahrain 76%; Lebanon 76%; Kuwait 77%; Yemen 78%; Iraq 85%; West Bank and Gaza 89%.

Jews still talk too much about what happened to them in the Holocaust. Iran 18%; Yemen 16%; Saudi Arabia 22%; Egypt 23%; Kuwait 24%; Lebanon 26%; Jordan 29%; Iraq 33%; Oman 42%; UAE 45%; Bahrain 51%; Qatar 52%; West Bank and Gaza 64%.

Jews don’t care what happens to anyone but their own kind. Iran 50%; Egypt 68%; Oman 70%; Lebanon 71%; Kuwait 73%; UAE 73%; Saudi Arabia 74%; Jordan 75%; Qatar 75%; Bahrain 75%; Iraq 76%; Yemen 80%; West Bank and Gaza 84%.

Jews have too much control over global affairs. Iran 49%; Oman 67%; Saudi Arabia 70%; Egypt 71%; Qatar 73%; UAE 73%; Bahrain 76%; Iraq 77%; Lebanon 77%; Jordan 78%; Kuwait 80%; Yemen 80%; West Bank and Gaza 88%.

Jews have too much control over the United States government: Iran 61%; Oman 67%; Saudi Arabia 70%; UAE 72%; Jordan 73%; Lebanon 73%; Qatar 73%; Egypt 74%; Bahrain 77%; Kuwait 78%; Yemen 79%; Iraq 85%; West Bank and Gaza 85%.

Jews think they are better than other people: Iran 52%; Lebanon 61%; Egypt 66%; Oman 66%; Qatar 67%; Bahrain 68%; UAE 68%; Saudi Arabia 69%; Kuwait 71%; West Bank and Gaza 72%; Jordan 73%; Yemen 76%; Iraq 80%.

Jews have too much control over the global media: Iran 55%; Bahrain 61%; Oman 65%; Egypt 69%; Saudi Arabia 69%; Qatar 70%; UAE 70%; Kuwait 72%; Lebanon 73%; Iraq 77%; Jordan 77%; Yemen 79%; West Bank and Gaza 88%.

Jews are responsible for most of the world’s wars: Iran 58%; Qatar 64%; Lebanon 65%; Oman 65%; UAE 65%; Kuwait 66%; Saudi Arabia 66%; Egypt 66%; Jordan 67%; Bahrain 71%; West Bank and Gaza 78%; Yemen 84%; Iraq 85%.

People hate Jews because of the way Jews behave: Iran 64%; Lebanon 76%; Bahrain 77%; Kuwait 80%; Egypt 81%; Oman 81%; Iraq 81%: Saudi Arabia 81%; Qatar 82%; UAE 82%; Jordan 84%; West Bank and Gaza 87%; Yemen 90%.

Iran has a complicated relationship with its Jewish community, and has a long way to go before it can be considered a safe haven for Jews, even if some Iranian Jews may disagree. Still, the ADL’s data makes it clear that Iran is not only the least anti-Semitic country in its region, it also scores far better on every one of the ADL’s eleven survey indicators by a statistically significant margin. That’s something worth thinking about.

Photo: Persian Jews celebrate the Jewish holiday of Sukkot in a Tehran synagogue last October. Credit: CNN screenshot.

]]>by Jasmin Ramsey

The title of this post is a quote from Shaul Bakhash, a George Mason University professor who moderated a panel discussion, “Iran, the Next Five Years: Change or More of the Same?“ at the Wilson Center today. “In a way, we’ve been here before,” said the esteemed scholar, referring [...]]]>

by Jasmin Ramsey

The title of this post is a quote from Shaul Bakhash, a George Mason University professor who moderated a panel discussion, “Iran, the Next Five Years: Change or More of the Same?“ at the Wilson Center today. “In a way, we’ve been here before,” said the esteemed scholar, referring to the presidencies of centrist leader Hashemi Rafsanjani and Mohammad Khatami, when the country was perceived as moving towards openness at home and abroad. But while Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s administration includes individuals with past ties to those movements, Bakhash says the conservatives “remain the strongest political body in Iran”.

While nothing can stay the same forever, many people worried (some still do) that the Islamic Republic would continue down a path of conservatism verging on radicalism before the surprise presidential election of Rouhani in June 2013. Since Rouhani took over from Mahmoud Ahmadinejad — whose former conservative allies couldn’t effectively unite in time to support another conservative into the presidency — those worries have changed. Now the question on everyone’s mind is: can Rouhani successfully navigate Iran’s contested political waters in his quest to implement foreign, economic and social policy reforms?

A lot depends on Iran’s 2016 parliamentary elections, according to panelist Bernard Hourcade, an expert on Iran’s social and political geography. “Elections matter In Iran”, said Hourcade, echoing Farideh Farhi. What happened in 2009 (when large groups of Iranians protested the election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and were violently repressed) proved that “elections have become a major political and social item in [Iranian] political life.”

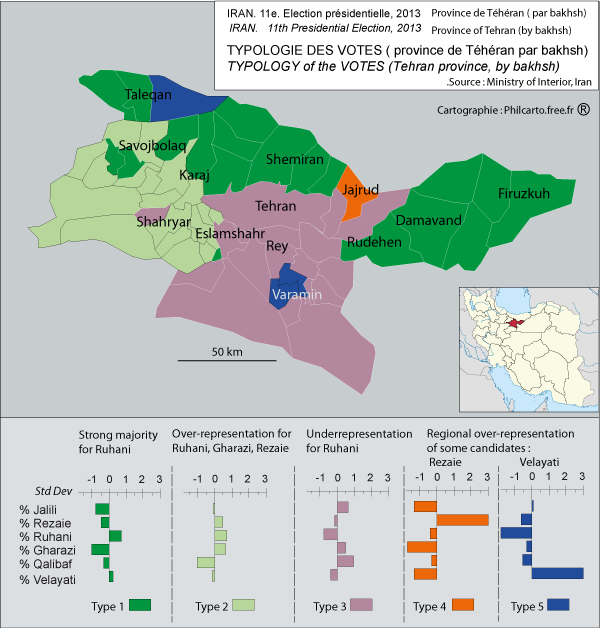

Hourcade uses official data to back up that point. Most interestingly, he shows that due to population migration patterns, the most important political divisions no longer exist between Iranian cities and villages, but between city centers and suburbs. Consider, for example, the typology of presidential votes for Rouhani in Tehran province. Hourcade’s diagram shows that while Rouhani had strong support in the northern part of Shemiran, he didn’t get a majority in central Tehran. Why that occurred is more difficult to answer, according to Hourcade, due to limited data resources.

Hourcade uses official data to back up that point. Most interestingly, he shows that due to population migration patterns, the most important political divisions no longer exist between Iranian cities and villages, but between city centers and suburbs. Consider, for example, the typology of presidential votes for Rouhani in Tehran province. Hourcade’s diagram shows that while Rouhani had strong support in the northern part of Shemiran, he didn’t get a majority in central Tehran. Why that occurred is more difficult to answer, according to Hourcade, due to limited data resources.

How political divisions play out in Iran’s upcoming parliamentary elections, which could give Iran’s currently sidelined conservatives more power, will also impact the Majles’ (parliament’s) reaction to the potential comprehensive deal with world powers over Iran’s nuclear program.

In other words, even if Iran’s rock star Foreign Minister can negotiate a final deal with the P5+1 (the U.S., Britain, France, China, and Russia plus Germany) that Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei approves, Iran’s parliament still has to ratify it, and if conservatives who oppose Rouhani dominate the majles, we may have another problem on our hands.

There were many other important points offered by Hourcade and his co-panelists, including Roberto Toscano, Italy’s former ambassador to Iran. He noted that former President Mohammad Khatami didn’t have the same chances as Rouhani because he was “too much out of the mainstream”. Rouhani, a centrist cleric and former advisor to Ayatollah Khamenei, wouldn’t have won the presidency without pivotal backing by both Khatami and Rafsanjani. So, as Toscano argues, Rouhani is in the mainstream (for now). But whether he and his allies will be able to maintain support from these important players moving forward, especially in 2016, will seriously influence whether he, like Khatami and Rafsanjani will be ultimately sidelined, or achieve a presidential legacy in Iran like nothing we’ve seen before.

Photo: Iranian President Hassan Rouhani walks by former Presidents Mohammad Khatami and Hashemi Rafsanjani following his June 2013 presidential vicotry. Credit: Mehdi Ghasemi/ISNA

]]>