The stakes could not be higher—or the issues tougher—as the world’s six major powers and Iran launch talks February 18 on final resolution of the Iranian nuclear crisis.

The goal “is to reach a mutually-agreed long-term comprehensive solution that would ensure Iran’s nuclear program will be exclusively peaceful,” says the temporary Joint [...]]]>

The stakes could not be higher—or the issues tougher—as the world’s six major powers and Iran launch talks February 18 on final resolution of the Iranian nuclear crisis.

The goal “is to reach a mutually-agreed long-term comprehensive solution that would ensure Iran’s nuclear program will be exclusively peaceful,” says the temporary Joint Plan of Action, which calls for six months of negotiations. If talks fail, the prospects of military action—and potentially another Middle East conflict—soar.

Six issues are pivotal to an accord. The terms on each must be accepted by all parties—Iran on one side and Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia and the United States on the other—or there is no deal. The Joint Plan notes, “This comprehensive solution would constitute an integrated whole where nothing is agreed until everything is agreed.”

1. Limiting Uranium Enrichment

Iran’s ability to enrich uranium is at the heart of the international controversy. The process can fuel both peaceful nuclear energy and the world’s deadliest weapon. Since 2002, Iran’s has gradually built an independent capability to enrich uranium, which it claims is only for medical research and to fuel an energy program. But the outside world has long been suspicious of Tehran’s intentions because its program exceeds its current needs. Iran’s only nuclear reactor for energy, in the port city of Bushehr, is fueled by the Russian contractor that built it.

Centrifuges are the key to enriching uranium. In 2003, Iran had fewer than 200 centrifuges. In 2014, it has approximately 19,000. About 10,000 are now enriching uranium; the rest are installed but not operating. To fuel a nuclear power reactor, centrifuges are used to increase the ratio of the isotope U-235 in natural uranium from less than one percent to between three and five percent. But the same centrifuges can also spin uranium gas to 90 percent purity, the level required for a bomb.

Experts differ on how many centrifuges Iran should be allowed to operate. Zero is optimal, but Iran almost certainly will not agree to eliminate totally a program costing billions of dollars over more than a decade. Iranian officials fear the outside world wants Tehran to be dependent on foreign sources of enriched uranium, which could then be used as leverage on Iran—under threat of cutting off its medical research and future nuclear energy independence.

Most experts say somewhere between 4,000 and 9,000 operating centrifuges would allow many months of warning time if Iran started to enrich uranium to bomb-grade levels. The fewer centrifuges, the longer Iran would need to “break out” from fuel production to weapons production.

So the basic issues are: Can the world’s major powers convince Iran to disable or even dismantle some of the operating centrifuges? If so, how low will Iran agree to go? And will Iran agree to cut back enrichment to only one site, which would mean closing the underground facility at Fordow?

A deal may generally have to include:

- reducing the number of Iran’s centrifuges,

- limiting uranium enrichment to no more than five percent.

- capping centrifuge capabilities at current levels.

In short, as George Shultz and Henry Kissinger say, a deal must “define a level of Iranian nuclear capacity limited to plausible civilian uses and to achieve safeguards to ensure that this level is not exceeded.”

2. Preventing a Plutonium Path

Iran’s heavy water reactor in Arak, which is unfinished, is another big issue. Construction of this small research reactor began in the 1990s; the stated goal was producing medical isotopes and up to 40 megawatts of thermal power for civilian use. But the “reactor design appears much better suited for producing bomb-grade plutonium than for civilian uses,” warn former Secretary of Defense William Perry and former Los Alamos Laboratory Director Siegfried Hecker.

For years, Iranian officials allowed weapons inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the U.N. nuclear watchdog, intermittent access to Arak. Inspectors have been granted more access since the Joint Plan of Action went into effect on January 20. But satellite imagery can no longer monitor site activity due to completion of the facility’s outer structure.

The reactor will be capable of annually producing nine kilograms of plutonium, which is enough material to produce one or two nuclear weapons. However, the reactor is at least a year away from operating, and then it would need to run for 12 to 18 months to generate that much plutonium. Iran also does not have a facility to reprocess the spent fuel to extract the plutonium. In early February, Iranian officials announced they would be willing to modify the design plans of the reactor to allay Western concerns, although they provided no details.

3. Verification

The temporary Joint Plan allows more extensive and intrusive inspections of Iran’s nuclear facilities. U.N. inspectors now have daily access to Iran’s primary enrichment facilities at the Nantaz and Fordow plants, the Arak heavy water reactor, and the centrifuge assembly facilities. Inspectors are now also allowed into Iran’s uranium mines.

Over the next six months, negotiations will have to define a reliable long-term inspection system to verify that Iran’s nuclear program is used only for peaceful purposes. A final deal will have to further expand inspections to new sites. The most sensitive issue may be access to sites suspected of holding evidence of Iran’s past efforts to build an atomic bomb. The IAEA suspects, for example, that Iran tested explosive components needed for a nuclear bomb at Parchin military base.

Iran may be forthcoming on inspections. Its officials have long held that transparency—rather than reduction of capabilities—is the key to assuring the world that its program is peaceful. They have indicated a willingness to implement stricter inspections required under the IAEA’s Additional Protocol—and maybe even go beyond it. But they are also likely to want more inspections matched by substantial sanctions relief and fewer cutbacks on the numbers of centrifuges in operation. At least four of the six major powers—the United States, Britain, France and Germany—will almost certainly demand both increased inspections and fewer, less capable centrifuges.

4. Clarifying the Past

The issue is not just Iran’s current program and future potential. Several troubling questions from the past must also be answered. The temporary deal created a Joint Commission to work with the IAEA on past issues, including suspected research on nuclear weapon technologies. Iran denies that it ever worked on nuclear weapons, but the circumstantial evidence about past Iranian experiments is quite strong.

Among the issues:

- research on polonium-210, which can be used as a neutron trigger for a nuclear bomb,

- research on a missile re-entry vehicle, which could be used to deliver a nuclear weapon, and

- suspected high-explosives testing, which could be used to compress a bomb core to critical mass.

Iran may be reluctant to come clean unless it is guaranteed amnesty for past transgressions—and can find a way to square them with its many vigorous denials. And any suspicions that Iran is lying will undermine even rigorous new inspections that verify Iran’s technology is now being used solely for civilian purposes.

On February 8, in a potential breakthrough, the IAEA and Iran agreed on specific actions that Iran would take to provide information and explanations of its past activities. “Resolution of these issues will allow the agency to verify the completeness and correctness of Iran’s nuclear activities,” says Kelsey Davenport of the Arms Control Association, “and help ensure that Tehran is not engaged in undeclared activities.” Resolving all past issues before a final agreement may prove difficult, however. Negotiations may instead produce a process for eventual resolution.

5. Sanctions Relief

Iran’s primary goal is to get access to some $100 billion in funds frozen in foreign banks and to end the many sanctions that have crippled the Iranian economy. Since the toughest U.S. sanctions were imposed in mid-2012, Iran’s currency and oil exports have both plummeted by some 60 percent.

The temporary Joint Plan of Action says a final agreement will “comprehensively lift UN Security Council, multilateral and national nuclear-related sanctions…on a schedule to be agreed upon.” (It does not, however, address sanctions imposed on other issues, such as support for extremist groups or human rights abuses.) The United States and the Europeans may want to keep some sanctions in place until they are assured that Iran is meeting new obligations.

The specter of the U.S. Congress will overshadow negotiations. Its approval will be required to remove the most onerous sanctions over the past five years. “The U.S. Congress will have to allow meaningful sanctions relief to Iran, just as Iran’s hard-liners are going to have to be convinced not to stand on principle when it comes to their ‘right’ to enrich and their demand to have all sanctions lifted,” says Brookings Institution scholar Ken Pollack, “The U.S. Congress is going to have to agree to allow Iran’s economy to revive and Tehran’s hard-liners are going to have to be satisfied with the revival of their economy and some very limited enrichment activity.”

6. The Long and Winding Road

The final but critical issue is timing: How long is a long-term deal? It will clearly require years to prove Iran is fully compliant. But estimates vary widely from five to 20 years. Another alternative is a series of shorter agreements that build incrementally on one another.

For all the big issues ahead, both sides have an interest in negotiating a deal. The world’s six major powers want to curtail more of Iran’s program, while Iran wants to revive its economy and normalize its international relations. If the negotiators succeed, they will make history. Their failure could open the path to a nuclear-armed Iran or a new war in the Middle East – or both.

– Joseph Cirincione is president of Ploughshares Fund and author of Nuclear Nightmares: Securing the World before It Is Too Late

This article was originally published on the Iran Primer

]]>via USIP

Iran has mixed feelings and conflicting interests in the Syrian crisis. Tehran has a strategic interest in opposing chemical weapons due to its own horrific experience during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. For years, President Saddam Hussein’s military used chemical weapons that killed thousands of Iranian soldiers. So [...]]]>

via USIP

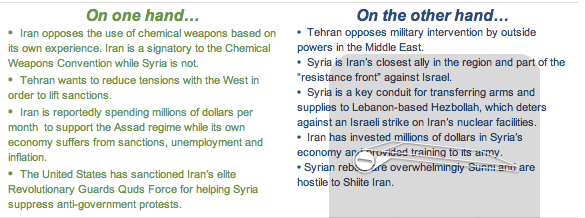

Iran has mixed feelings and conflicting interests in the Syrian crisis. Tehran has a strategic interest in opposing chemical weapons due to its own horrific experience during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. For years, President Saddam Hussein’s military used chemical weapons that killed thousands of Iranian soldiers. So Iran actually shares interests with the United States, European nations and the Arab League in opposing any use of chemical weapons.

But the Islamic Republic also has compelling reasons to continue supporting Damascus. The Syrian regime is Iran’s closest ally in the Middle East and the geographic link to its Hezbollah partners in Lebanon. As a result, Tehran vehemently opposes U.S. intervention or any action that might change the military balance against President Bashar Assad.

The Iran-Syria alliance is more than a marriage of convenience. Tehran and Damascus have common geopolitical, security, and economic interests. Syria was one of only two Arab nations (the other being Libya) to support Iran’s fight against Saddam Hussein, and it was an important conduit for weapons to an isolated Iran. Furthermore, Hafez Assad, Bashar’s father, allowed Iran to help create Hezbollah, the Shiite political movement in Lebanon. Its militia, trained by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, has been an effective tool against Syria’s archenemy, Israel.

Relations between Tehran and Damascus have been rocky at times. Hafez Assad clashed with Hezbollah in Lebanon and was wary of too much Iranian involvement in his neighborhood. But his death in 2000 reinvigorated the Iran-Syria alliance. Bashar Assad has been much more enthusiastic about Iranian support, especially since Hezbollah’s “victorious” 2006 conflict with Israel.

In the last decade, Iran’s Revolutionary Guards have trained, equipped, and at times even directed Syria’s security and military forces. Hundreds of thousands of Iranian pilgrims and tourists visited Syria before its civil war, and Iranian companies made significant investments in the Syrian economy.

Fundamentalist figures within the Guards view Syria as the “front line” of Iranian resistance against Israel and the United States. Without Syria, Iran would not be able to supply Hezbollah effectively, limiting its ability to help its ally in the event of a war with Israel. Hezbollah wields thousands of rockets able to strike Israel, providing Iran deterrence against Israel — especially if Tel Aviv chose to strike Iran’s nuclear facilities. A weakened Hezbollah would directly impact Iran’s national security. Syria’s loss could also tip the balance in Iran’s rivalry with Saudi Arabia, making the Wahhabi kingdom one of the most influential powers in the Middle East.

In the run up to a U.S. decision on military action against Syria, Iranian leaders appeared divided.

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and hardline lawmakers reacted with alarm to possible U.S. strikes against the Assad regime. And Revolutionary Guards commanders threatened to retaliate against U.S. interests. The hardliners clearly viewed the Assad regime as an asset worth defending as of September 2013.

But President Hassan Rouhani, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif and former President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani adopted a more critical line on Syria. “We believe that the government in Syria has made grave mistakes that have, unfortunately, paved the way for the situation in the country to be abused,” Zarif told a local publication in September 2013.

Rafsanjani, still an influential political figure, reportedly said that the Syrian government gassed its own people. This was a clear breach of official Iranian policy, which has blamed the predominantly Sunni rebels. Rafsanjani’s words suggested that he viewed unconditional support for Assad as a losing strategy. His remark also earned a rebuke from Khamenei, who warned Iranian officials against crossing the “principles and red lines” of the Islamic Republic. Khamenei’s message may have been intended for Rouhani’s government, which is closely aligned with Rafsanjani and seems to increasingly view the Syrian regime as a liability.

Regardless, a significant section of Iran’s political elite could be amenable to engaging the United States on Syria. Both sides have a common interest: preventing Sunni extremists from coming to power in Damascus. Iran and the United States also prefer a negotiated settlement over military intervention to solve the crisis. Tehran might need to be included in a settlement given its influence in Syria. Negotiating with Iran on Syria could ultimately help America’s greater goal of a diplomatic breakthrough, not only on Syria but Tehran’s nuclear program as well.

– Alireza Nader is a senior international policy analyst at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation.

*Read Alireza Nader’s chapter on the Revolutionary Guards in “The Iran Primer”

Photo Credits: Bashar Assad and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei via Leader.ir, Syria graphic via Khamenei.ir Facebook

]]>via Iran Primer

The United States has imposed several layers of sanctions against Iran—for widely diverse reasons—dating back to the 1979 revolution. Tehran now wants relief from sanctions as part of any diplomatic deal on its controversial nuclear program. But lifting sanctions is often harder than imposing them—and [...]]]>

via Iran Primer

The United States has imposed several layers of sanctions against Iran—for widely diverse reasons—dating back to the 1979 revolution. Tehran now wants relief from sanctions as part of any diplomatic deal on its controversial nuclear program. But lifting sanctions is often harder than imposing them—and varies depending on the issues, origins and methods imposed.

What types of sanctions has the United States imposed on Iran?

Sanctions have been the policy tool of choice used by six presidents to deal with Iran. Since the 1979 revolution, the White House has issued 16 executive orders and Congress has passed nine acts imposing punitive sanctions on Iran in four waves.

The first wave of U.S. sanctions, from 1979 to 1995, was a response to the U.S. embassy hostage crisis and Tehran’s support for extremist groups in the region.

The second wave of sanctions, from 1995 to 2006, sought to weaken the Islamic Republic by targeting its oil and gas industry and denying it access to nuclear and missile technology. U.S. sanctions also targeted any company in a third country that invested in Iran’s energy sector, a move to compel allies to adopt a unified stance against Iran.

The third wave, from 2006 to 2010, was imposed chiefly due to concerns over Tehran’s nuclear ambitions, but also included punitive measures for Iran’s human rights violations. Sanctions targeted almost every major chokepoint in Iran’s economy.

The latest wave of sanctions since 2010 includes some of the toughest restrictions the United States has ever imposed on any country. They target Iran’s Central Bank and its ability to repatriate oil revenues as well as many transportation, insurance, manufacturing and financial sectors.

The first two waves of sanctions were unilaterally imposed by Washington. But the last two included similar measures imposed by U.S. allies and the United Nations, generating almost a global sanctions regime against Iran.

What would the United States need to do to lift sanctions?

The standard for lifting U.S. sanctions is high. The president could nullify the White House executive orders imposed over the years. But nearly 60 percent of these sanctions have also been codified into law by Congress, which puts amending or repealing sanctions beyond the president’s control. Congress would also have to take action.

For example, executive orders banning U.S. trade with Iran — under Executive Orders 12957, 12959 and 13059 — were subsequently written into the law when Congress passed the Iran Freedom Support Act in 2006 and the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act in 2010. Similarly, sanctions on Iran’s energy and petrochemical sector under Executive Order 13590 and human rights violators under Executive Order 13606 were subsequently codified into law through the Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act of 2012.

The president could still exercise his waiver authority to exempt countries, entities and individuals from sanctions. He could also mandate greater flexibility in determining violations and enforcing penalties. The Clinton and Bush administrations opted for the latter option and never determined any country in violation of U.S. sanctions, which could have damaged relations with US allies.

What steps would Iran have to take to get sanctions lifted?

Sanctions have become so extensive and so intricately woven that the United States will probably have a hard time offering significant or tangible relief unless Iran reverses major aspects of its domestic and foreign policies. The same applies to the 34-year-old state of emergency on Iran, which gives the president broad powers to unilaterally impose sanctions or other punitive measures.

The 16 executive orders and nine Congressional acts are also not tied only to the nuclear issue. More than 80 percent of the sanctions are linked to Iran’s broader foreign or domestic policies. As such, not all have the same standards to be lifted.

On Terrorism: Restoration of U.S.-Iran trade relations would first require that the United States remove Iran from the list of state sponsors of terrorism, which Tehran has been on since the list was created in the 1980s. And the requirements are stiff. Tehran would notably have to cut ties to Hezbollah, a Lebanese Shiite militia and political party that Tehran helped create in the early 1980s, as well as several other movements that use violence.

Tehran would also have to provide assurances — and proof — that it had abandoned international terrorism and support for extremist groups. The White House would then have to certify to Congress that Iran had not provided support for terrorism for at least six months, timing that could delay implementation of any diplomatic deal. Congress could block Iran’s removal from the list through a joint resolution, which would in turn be subject to a presidential veto. Congress could override the veto with a two-thirds majority, however.

On Human Rights: Ending sanctions imposed for human rights violations under the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act would require Iran to take several steps, including:

- unconditional release of all political prisoners;

- conducting a transparent investigation into the killings, arrests and abuse of protestors after the disputed 2009 presidential election;

- ending human rights violations;

- and establishing an independent judiciary.

On the Nuclear Program: The United States has no clear criteria for removing these sanctions. The basic demands by the world’s six major powers include:

- halting all enrichment of uranium up to 20 percent,

- neutralizing the current stockpile of uranium enrich to 20 percent

- mothballing the new enrichment facility build into the mountains of Fordo.

- accepting maximum level of transparency and intrusive inspections,

- resolving all the outstanding issues with the International Atomic Energy Agency,

- and abiding by the six UN Security Council resolutions demanding suspension of uranium enrichment and reprocessing activities.

But most US sanctions are multipurpose. For example, termination of measures under the Iran Sanctions Act , which is at the core of U.S. sanctions, requires:

- that the president to certify that Iran has ceased efforts to design, develop or acquire nuclear, chemical and biological weapons, as well as ballistic missile technology;

- that Tehran has been removed from the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism;

- and that Iran poses no significant threat to U.S. national security interests or its allies.

What obstacles would the White House face in lifting sanctions from Congress, political lobbies, public opinion or other players?

Lifting U.S. sanctions could be complicated by politics, particularly discordant views between the White House and Congress. Some lawmakers seem less interested in a diplomatic resolution–or less convinced of its feasibility. They are not swayed by the views of U.S. allies. Others would actually prefer to impose additional sanctions.

So in Washington’s highly politicized climate, Congress may not easily defer to the president on sanctions relief, especially given powerful lobbies on the issue.

Easing sanctions may also not automatically alter or increase international trade with Iran, given economic realities and business wariness. Sanctions have significantly altered basic trade and consumption patterns that may be hard to change—and may limit or delay any benefits to Iran. Some companies and countries that have shifted away from Iran over the years are unlikely to rush back without solid assurances that sanctions relief is not just temporary. Uncertainty would make them hesitant to re-engage.

For example, one possibility in a diplomatic deal would be short-term suspension of sanctions–as an interim step—so the two sides have time for building confidence between each other and for winning political support at home for concessions. One of Iran’s top priorities is to get sanctions relief so that it can export more oil, which accounts for up to 80 percent of its export earnings. But the international oil industry may hesitate to reengage during a short-term suspension. Iranian crude also has specific characteristics that would require reconfiguration of refineries, an expensive step without prospects of an enduring deal.

All in all, the nature of multi-purpose and multi-layered sanctions has confused their strategic purpose, while constraining Washington’s ability to respond to positive actions with requisite nimbleness. Over time, as they has simultaneously grown and ossified, the sanctions have become a less-than-optimal tool to advance negotiations in a diplomatic process where a scalpel, rather than a chainsaw, is required.

Would the United States remove the diverse sanctions in the same way?

The timing and means of removing sanctions will almost certainly vary.

- Politically sensitive sanctions–notably for Iran’s human rights violations and support of militant groups–are unlikely to be on the menu in the near future.

- Restrictions on oil and financial transactions are the crown jewels of the sanctions regime in the eyes of Western policy makers. Neither Washington nor its European Union partners are likely to suspend them without significant Iranian guarantees about Tehran’s nuclear concessions. But the reality of suspending sanctions is also not easy either. For instance, both the president and Congress would have to act to allowing Iran to reach its previous petroleum exports,including:

- revoking Executive Order 13622,

- using national security waiver to permit other states to buy more oil from Iran under the National Defense Authorization Act of 2012,

- permitting financial transactions with Iran’s energy, shipping and port sectors, which are all declared “entities of proliferation concern” under the Iran Freedom and Counter-proliferation Act of 2012,

- waiving sanctions under TRA and IFCA to allow the provision of insurance and reinsurance for shipping Iranian oil,

- and waiving the ban on repatriating Iran’s oil revenue under TRA. Waivers need to be renewed every 120 or 180 days.

Almost all Iranian major energy and shipping companies are also blacklisted by the Treasury Department, either as entities supporting terrorism (under Executive Order 13224) or for being involved in proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction under Executive Order 13382. Foreign companies will be more than reluctant to work with these companies unless they are delisted.

The only remaining option would be to suspend other sanctions that tangibly affect Iran’s economic well-being. The United States could allow Iran to import or export specific goods that produce revenue or help Iran’s manufacturing sector. The P5+1 world major powers — the United States, Britain, China, France, Germany and Russia — chose a similar route in the February and April 2013 negotiations with Iran in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Their offer to relax sanctions on Iran’s petrochemical sales and gold trade was meaningful, but it was not proportionate to the concessions expected from Tehran.

Given the complexities, another U.S. option might be to focus on European sanctions, which are more elastic and lack clear criteria for termination. Their repeal requires a unanimous decision by all 28 member states of the European Union. Building consensus, however, is not always a straight forward enterprise in Europe. Also, there is now so much overlap between the U.S. and EU sanctions that a unilateral EU removal of sanctions might have little impact on the ground. One-sided EU concessions also risk being seen by Tehran as a tactical ploy to maintain U.S. sanctions in place indefinitely.

Diplomatic talks are expected to resume in the fall. The challenge for world’s six major powers will be devising a package of incentives, including some degree of sanctions relief that is achievable both politically and legally while also genuinely addressing Iranian concerns. The challenge for the new Iranian government will be to respond in kind.

Ali Vaez is the International Crisis Group’s senior Iran analyst.

Click here to see Vaez discuss sanctions at a July 22 event at the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars.

]]>I don’t know the answer to the question I’ve posted above, but today’s news may offer an indication:

The EU imposes new sanctions against Iran’s nuclear program and reaffirms its said commitment to reaching a peaceful, diplomatic solution:

…the objective of the EU remains to achieve a comprehensive, negotiated, long-term settlement, [...]]]>

I don’t know the answer to the question I’ve posted above, but today’s news may offer an indication:

The EU imposes new sanctions against Iran’s nuclear program and reaffirms its said commitment to reaching a peaceful, diplomatic solution:

…the objective of the EU remains to achieve a comprehensive, negotiated, long-term settlement, which would build international confidence in the exclusively peaceful nature of the Iranian nuclear programme, while respecting Iran’s legitimate rights to the peaceful uses of nuclear energy in conformity with the NPT, and fully taking into account UN Security Council and IAEA Board of Governors’ Resolutions.

Israel nods approvingly but doesn’t rejoice:

[Benjamin] Netanyahu, speaking Tuesday at the start of a meeting in Jerusalem with European Union member state ambassadors, called the sanctions “tough” and said Iran was “the greatest threat to peace in our time.”

“These sanctions are hitting the Iranian economy hard, (but) they haven’t yet rolled back the Iranian program. We’ll know that they’re achieving their goal when the centrifuges stop spinning and when the Iranian nuclear program is rolled back,” he said.

As does the former EU and US terrorist-designated organization the Mujahadeen-e Khalq (aka MEK, NCRI, PMOI) while reaffirming its commitment to regime change in Iran:

Therefore, although comprehensive sanctions are an essential and indispensible element to stop the clerical regime’s nuclear weapons project, the ultimate and definitive solution for the world community to rid itself of the terrorist mullahs’ attempt to acquire nuclear weapons is a regime change by the Iranian people and Resistance. Thus, recognizing the Iranian people’s efforts to overthrow religious fascism and to establish democracy in Iran is more essential than ever.

Iran complains loudly while tooting its resistance regime horn and allegdly hitting back against cyber attacks waged against its nuclear program.

And all the while average Iranians (and terminally ill ones) continue to carry the brunt of the weight:

]]>The measures come as Iran’s economy continues to reel in the wake of previous Western sanctions targeting the country’s crucial oil exports and access to international banking networks. Iranians are suffering economically amid inflation and the sharp devaluation of the Iranian currency against the dollar.

Shop owners in downtown Tehran said that prices had risen 50% since last month and that they were expecting things to only get worse.

Amir Mosayan, who sells watch batteries wholesale, said that immediately following the sanctions the price of his goods went up 70%.

via the United States Institute of Peace

What are the primary reasons that the Iranian rial has lost half of its value against the U.S. dollar in just one year? Iran’s currency was valued at about 10,000 rials to the dollar in the summer of 2011. It plummeted to more than [...]]]>

via the United States Institute of Peace

What are the primary reasons that the Iranian rial has lost half of its value against the U.S. dollar in just one year? Iran’s currency was valued at about 10,000 rials to the dollar in the summer of 2011. It plummeted to more than 20,000 to the dollar in the summer of 2012.

What are the primary reasons that the Iranian rial has lost half of its value against the U.S. dollar in just one year? Iran’s currency was valued at about 10,000 rials to the dollar in the summer of 2011. It plummeted to more than 20,000 to the dollar in the summer of 2012.

Inflation in Iran’s economy has not been this bad since the end of the Iran-Iraq War or the economic crisis of the early 1990s, which also caused high inflation. The rial’s value began to slide rapidly at the beginning of 2012 after the United States announced new sanctions above and beyond the latest U.N. sanctions. The slide was due partly to the psychology of sanctions.

The government also went back to a tiered currency regime similar to what it had in the 1980s, during the Iraq-Iran War, and through the 1990s. Various types of imports and transactions had different exchange rates. Today, the official exchange rate is used for strategic imports such as food and medicine. That is another reason the price of rice did not go up a lot.

The price of chicken went up a lot, however, because Iran is not a socialist country. It cannot control the price of everything. Chicken farmers and wholesale buyers respond to market prices. The government capped the store price of chicken, but the price of chicken feed was going up because much of it is imported.

The state also stopped its phased subsidy reductions. It had planned to further cut longstanding subsidies for electricity, gasoline and utilities, but parliament told the president in the spring to continue the current level of subsidies. The president initially refused, but under parliamentary pressure has deferred any new price hikes. So U.S. and E.U. sanctions have forced the Islamic Republic to stop the subsidy reduction program that the International Monetary Fund and the Ahmadinejad government had been working on for years.

What roles have U.S. and international sanctions played in Iran’s currency drama? In July 2012, Parliamentary Speaker Ali Larijani said that only 20 percent of Iran’s economic problems were due to international sanctions. What is your assessment?

It is hard to put a number on what percentage U.S. and E.U. sanctions have on currency devaluation and inflation because both are produced by a combination of factors– what individuals do based on future uncertainty and the sometimes contradictory policies of the government.

The Central Bank has suggested that it may change the official exchange rate. What impact will that have? Will it solve the problem? Are there any side effects or dangers?

Some economists, including many in Iran, say the country needs a single rate. People make money playing the official and unofficial currency rates off each other. But the state does not have the luxury of unifying the rial’s value. So it is trying all sorts of stop-gap measures, which in the long term are harmful. They create opportunities for speculation. But the state, which is dealing in the short term, is in a double bind. Letting the official rate devalue would lead to such an inflationary burst that prices could go up even more.

Semira N. Nikou of the United States Institute of Peace Iran Primer recently interviewed Iranian regime insider and staunch Ahmadinejad critic Seyed Hossein Mousavian who discussed the Iranian perspective on prospects for U.S.-Iran rapprochement. I have republished the entire article below. The clip above is Mousavian’s February lecture at Princeton [...]]]>

Semira N. Nikou of the United States Institute of Peace Iran Primer recently interviewed Iranian regime insider and staunch Ahmadinejad critic Seyed Hossein Mousavian who discussed the Iranian perspective on prospects for U.S.-Iran rapprochement. I have republished the entire article below. The clip above is Mousavian’s February lecture at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and External Affairs. He begins by discussing the origin and direction of Iran’s nuclear program and points out that Iran’s nuclear program began during the Shah’s reign with U.S. assistance and

- if the Shah had not been overthrown by the Islamic Revolution in 1979, and were in power today, Iran would have a large nuclear arsenal. The West thus owes a debt of gratitude to the Islamic Republic because Iran has neither produced a nuclear bomb nor diverted its nuclear program toward military purposes.

Oh, the irony…

Hossein Mousavian: Iran is Ready to Negotiate–If

By Semira N. Nikou

Seyed Hossein Mousavian was foreign policy adviser to former nuclear negotiator, Ali Larijani (2005-07), former spokesperson of Iran’s nuclear negotiation team (2003-05), former head of the Foreign Relations Committee of the National Security Council of Iran (1997-2005), and the former ambassador to Germany (1990-97). He is currently a visiting research scholar at Princeton University. This interview was conducted after Mousavian’s first public presentation since his arrest in Iran in April 2007. He spoke to an audience of 5,000 people at Chautauqua Institution.

- What are the prospects, realistically, for progress this year in diplomatic efforts? What are the realistic options for a U.S.-Iran rapprochement?

The supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, is the ultimate decision-maker and he will be ready to negotiate once Iran is offered the right package. He does not object to transparency because he already issued a fatwa in 1995 against weapons of mass destruction. But he is against discrimination, suspension [of uranium enrichment], and the deprivation of Iran’s rights under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

I do not understand the notion that the supreme leader is not willing to negotiate—considering how the issue of Iran’s right to enrichment has never been approached properly. Ultimately, prospects for negotiation depend on whether the P5+1 (five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council plus Germany) offers Iran an acceptable package.

Even during the 2003-2005 negotiations, Iran’s confidence-building measures—including suspension of enrichment, implementation of the Addition Protocol, and inspections beyond those required by NPT—all had to be approved by the supreme leader. Otherwise, we would not have been able to implement those policies. This is the same leader.

By early 2005, the supreme leader had lost confidence in the ability of the Europeans—Iran’s main negotiating interlocutors at the time—to deliver on their promises. This was before Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s presidency.

Now, after eight years, there is still a dispute among the P5+1 members over Iran’s rights. In 2005, Russia, China, Germany, and even France were prepared to recognize Iran’s rights to enrichment, but the United Kingdom and the United States were not. The U.S. position at the time was that Iran could have not any centrifuges.

Since Barack Obama won the presidency, there has been a clear change. As far as I understand, the United States is prepared to recognize Iran’s rights to enrichment under certain conditions—such as intrusive inspections, temporary limit on the number of centrifuges, etc.

I am surprised that the Europeans—led by France—are now resisting. Paris is pushing the United States to discuss enrichment at the end of negotiations, rather than at the beginning. So, while Washington has come to understand that no agreement can be reached without first recognizing Iran’s rights, France has a different position.

That is why the P5+1 policy towards Iran has failed and will continue to fail until there is willingness to accept Iran’s rights to peaceful nuclear enrichment. The suspension era is over.

It is simply not acceptable for P5+1 countries, which control 98 percent of the world’s stockpile of nuclear weapons, to deprive others from the pursuit of peaceful nuclear energy and fuel cycle.

- What conditions need to be met for negotiations to be successful? What does Iran need to do? What does the U.S. need to do?

The P5+1 want a step-by-step approach toward negotiations, but Iran wants to see the final result. The step-by-step approach does not work. A comprehensive package acknowledging Iran’s right to enrichment should be placed on the table at the start of negotiations. In other words, both parties should see the final outcome.Otherwise, the Iranians will not enter a road where they cannot see the end.

After agreeing on a comprehensive package, the parties can then further negotiate on the implementation of the package in a phased manner, with an agreed upon timetable. Without a timetable, Tehran will again hesitate to enter an agreement given its concerns about the P5+1’s intentions to play with time and prolong the negotiation process.

On the nuclear issue, the end state for the Iranians is full rights under the NPT, without discrimination over enrichment. Other countries enrich but do not face sanctions. The nuclear impasse will not be resolved as long as U.N. resolutions are enforced because they require Iran to indefinitely suspend enrichment and provide access to sites and scientists for an indefinite period. These conditions extend beyond the framework of NPT.

Parties negotiating with Iran have pushed for measures beyond the NPT and the Additional Protocol, with no definition of what those measures are and no limit on their scope. That is why I think Iran will never accept these resolutions.

- What would convince Iran to cooperate with the world’s six major powers?

The focal point of the P5+1 negotiations should be assurances about the peaceful nature of the Iranian nuclear program and non-diversion toward weapons program in the future. If the P5+1 is seeking the above outcomes, then talking about suspension—especially indefinite suspension—is both meaningless and useless. Suspension has nothing to do with transparency. Iran views indefinite suspension as a way for the P5+1 to buy time for a long-term ban on Iran’s enrichment program and ultimately its discontinuation.

Instead, the P5+1 can ask Iran for objective guarantees. The Europeans are the ones who first introduced the term “objective guarantees” in 2003-04, during the Paris Agreement. We [the Iranian negotiating team, of which Mousavian was a part] asked them to define what they meant, including the measures they expected from Iran for full transparency. They were never able to fully define what they meant.

The P5+1 can never ask Iran to give the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) access that goes beyond NPT and the Additional Protocol for an unlimited period. That is clear discrimination and the Iranian parliament would never accept it. But if the P5+1 asks for confidence-building measures beyond NPT for only a short term, then it is possible because Iran showed such gestures when Dr. Rowhani and Dr. Ali Larijani’ were chief negotiators.

- What steps could Iran take to build confidence?

We need a fair and balance “solution package” as a face-saving exit for both parties. To meet Iran’s bottom-line requirements, the P5+1 should respect the rights of Iran under the NPT, including its right to uranium enrichment; lift the sanctions; remove Iran’s case from UN Security Council and normalize nuclear cooperation with Iran under NPT.

In response, Iran could demonstrate objective guarantees, more transparency and confidence-building measures in a number of ways :

- Commit not to enrich uranium above 5 percent during a period of confidence-building—as long as the international community sells it fuel for the Tehran Research Reactor, which uses 20 percent enriched fuel (Iran’s Foreign Minister, Ali Akbar Salehi, made this offer in February 2010.)

- Adhere to all international nuclear treaties at the maximum level of transparency and cooperation as defined by the IAEA.

- Take steps toward regional and international cooperation for enrichment activities within Iran.

- Limit enrichment activities to its actual fuel needs.

- Export all enriched uranium not used for domestic fuel production and refraining from reprocessing spent fuel from research reactors for a period of confidence building.

- Resolve all IAEA’s remaining technical issues within the “Modality Agreement” or “Work Plan” signed between ElBaradei and Larijani in 2007.

I also think that a parallel, comprehensive agreement on Iran-U.S. bilateral relations is essential for achieving a realistic, face-saving solution to the nuclear issue. This package should be negotiated between Tehran and the United States directly, while Iran’s nuclear issue can be negotiated within the framework of the P5+1 talks.

- What role does domestic politics play in Iran’s position?

A very substantial one. The reality is that the overwhelming majority of Iranians are pro-nuclear technology.

Before 1979, full rights on the nuclear program was a red line for the shah, who demanded full rights—including reprocessing and enrichment—under the NPT. After the revolution, the Islamic Republic also eventually came to view the nuclear program as a red line. It was so under the presidencies of Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, Mohammad Khatami, and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Therefore, it does not matter whether moderates, reformists, or principlists are in power or whether we have a monarchical system or an Islamic Republic. The 50-year history of Iran’s nuclear program has proven that it has always been a red line, regardless of the governing system.

- How will heightened sanctions against Iran—both economic and human rights –affect future negotiations?

Sanctions have not, and will not, change Iran’s nuclear posture. This is just a reality that Iran’s interlocutors have to come to terms with.

After three decades, unilateral and multilateral sanctions against Iran’s nuclear program have not led to the intended results. For example, they have failed to change Iran’s nuclear policy, the Iranian population still views the nuclear program as a national right. And Iran has been able to acquire long-range missile capabilities, a nuclear fuel cycle, and advanced chemical and biological technologies.

But there is also another reality that it is very difficult to reverse sanctions, particularly the unilateral ones imposed by the United States Congress. Existing U.S. legislation does not endow the president with the authority to waive or terminate sanctions in response to goodwill gestures on Iran’s part.

It is the understanding of these dynamics that have made Iran more insistent on seeing the end game at the beginning of negotiations. In other words, recent sanctions have made Iran more suspicious of the United States intentions. Tehran does not see unilateral sanctions as instruments of pressure but in fact as mechanisms promoted to make a comprehensive agreement impossible and maintain the regime change scenario always on the table.

- Russia has proposed a “step-by-step” proposal for nuclear negotiations between Iran and the P5+1. What are the prospects, realistically, for the Russian initiative?

The initiative is a step forward but it is not a new proposal. The Russians first presented a similar plan to the United States in October 2010. Now, after the failure of negotiations in Geneva and Istanbul, Moscow believes the proposal can be a breakthrough.

I do not know the plan’s details but if it is a step-by-step one, it can only be successful if does not promote yet another round of suspension and it defines an end game entailing the following:

- Iran’s full rights to enrichment

- Lifting of sanctions

- Removal of Iran’s nuclear file from the U.N. Security Council and the IAEA Board of Governors

Engagement is both logical and realistic. But in the absence of a negotiable framework, the two parties will not be able to compromise. If the focus is on making Iran’s program transparent and assuring its peacefulness, then a framework for negotiations can be developed. But if the idea is to force Iran to do something that no other country is asked to do, then there will be no agreed upon framework for talks. Even if there are meetings, they will not go anywhere.

]]>But what is the real nature of [...]]]>

But what is the real nature of Iran’s relationship with the Taliban? According to Mohsen Milani, chairman of the Department of Government and International Affairs at the University of South Florida, Iran and the Taliban are ideological foes who share certain strategic interests, or rather, common enemies. While relations remain limited, the two have been brought closer together by the continued US-NATO occupation of Afghanistan.

An Iran Primer Q&A with Milani which I’ve republished below discusses Iran’s ties to the Taliban.

• What is the status of Iran’s relations with the Taliban today? Have there been significant changes since 2001?

The Islamic Republic of Iran has no official relation with the Taliban. Nor do the Taliban have an office or a representative in Tehran, as do many non-state actors, such as HAMAS. At the same time, Tehran has recognized that the Taliban have remarkable resiliency and are an integral component of the Afghan society that cannot be ignored. As there have been persistent reports that President Hamid Karzai, the United States, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia all have opened their channels of communications with the Taliban, Tehran is determined not to become marginalized and seems to have tried to open its own non-diplomatic and secret channels of communication. But the Taliban are not monolithic, and it is not clear which faction Iran is seeking to establish relations.

• How has Iran’s view of the Taliban changed since the U.S. intervention in Afghanistan in 2001?

Iran’s views of the Taliban have changed considerably since 2001. Iran did not recognize the Taliban government and considered them an ideological nemesis and a major security threat that was created by Pakistan’s ISI, with generous financial support from Saudi Arabia partly for the purpose of spreading Wahhabism and undermining Iran. When the Taliban were in power in the 1990s, Iran, along with India and Russia, provided significant support to the Northern Alliance, which was the principal opposition force to Taliban rule and eventually dislodged them. Iran also contributed to dismantling the Taliban regime and to establishing a new government in Kabul in 2001.

Today, the Taliban have evolved into a formidable armed organization fighting U.S. and NATO troops in Afghanistan. Ironically, the strategic interests of Tehran and Taliban have converged today, as each, independent of the other and for different reasons, oppose the presence of foreign troops in Afghanistan and demand their immediate and unconditional withdrawal.

• Is Iran providing tangible financial, military or political support for the Taliban?

There have been numerous public reports about support for the Taliban coming from Iran. There are reports that elements within the Revolutionary Guards may have transferred long-range rockets to the Taliban and provided training for the Taliban. In February 2011, British forces reportedly intercepted in Afghanistan a shipment of 48 122-mm rockets that they claimed had originated from Iran. Spokesmen of the Islamic Republic have consistently denied all these allegations. Such denials, even if we assume their validity, do not preclude the possibility that non-state actors within Iran may be used by the government to provide weapons or training to some factions within the Taliban organization.

From a strategic perspective, the Iranian government looks at the Taliban as a useful enemy that is undermining the interests of its other enemy, namely the United States. Therefore, it should not be surprising at all if the Iranian government supports the Taliban or if it looks the other away as behind-the-scenes support is provided by Iran’s non-state actors to the Taliban. Such support, however, appears to be very limited. The apparent goal is to empower the Taliban sufficiently to remain a major headache to the United States, but not to an extent that would allow them to seriously undermine the Karzai government or become the dominant force in all of Afghanistan.

• What is Tehran’s position on a Taliban-controlled government in Kabul?

A Taliban-dominated government is clearly not in Iran’s long-term interests, since it would generate considerable tension and conflict between Iran and Afghanistan and would inevitably lead Pakistan, and to a lesser extent Saudi Arabia, becoming dominant foreign powers in Afghanistan, which Tehran vehemently opposes. At the same time, Tehran has for many years maintained that political stability in Afghanistan can be achieved only if the government reflects the rich ethnic and sectarian diversity of Afghanistan itself. Iran, more than anything else, wants to see a stable and friendly government in Kabul. Tehran now seems convinced that without Taliban participation in the government, as a partner but not as the main force, stability would be unattainable.

• What is the state of Tehran’s relations with the Afghan government of President Hamid Karzai?

The bilateral relationship remains friendly, but not devoid of tension. Karzai has deftly managed to simultaneously have good relations with Tehran and Washington. Tehran continues with its heavy involvement in Afghan reconstruction, and trade between the two countries has increased substantially.

Still, Tehran has not abandoned its support for its traditional allies among the non-Pushtun Afghans, notably the Northern Alliance and the Shiite Hazarats. Tehran continues to express its displeasure with the way Kabul has handled the relatively free crossing of the Jondollah terrorist group into Iran, and with the flow of narcotics into Iran.

The major tension between Kabul and Tehran, however, is their diametrically opposed views regarding the presence and future of U.S./NATO troops. Tehran has attempted in vain to convince Karzai to call for the withdrawal of Western troops. Tensions between the two neighbors are likely to increase if there is a new agreement between Washington and Kabul about establishing permanent U.S. military bases in Afghanistan.

• How does Iranian influence in Afghanistan compare to its influence in Iraq? Which of the two countries is more important to Iran strategically?

Strategically, economically, and ideologically, Iraq is much more important than Afghanistan for Iran. Iran also exerts much more influence and has much more leverage in Iraq than in Afghanistan. Iran’s friends are much more organized in Iraq than they are in Afghanistan. Trade between Iran and Iraq has increased substantially, surpassing trade between Iran and Afghanistan. Iraq is now one of Iran’s major trading partners.

Politically and ideologically, Iran is much closer to the Shiite-dominated government in Baghdad than to the Sunni/Pushtun-dominated government of Hamid Karzai. While good relations with Karzai are important for Tehran, the relationship does not have profound international ramifications. Afghanistan’s strategic importance for Iran lies in the fact that American troops are stationed there. The case of Iraq is fundamentally different. Close relations between Tehran and Baghdad — two major oil exporters — or a political alliance between the two would be a game changer and would have significant economic ramifications for the world. It could also change the strategic balance of power in the oil-rich Persian Gulf.

]]>The allegations were first brought to light by New York Times correspondent Dexter Filkins. Filkins later confirmed the exchanges of cash with Karzai himself, who [...]]]>

The allegations were first brought to light by New York Times correspondent Dexter Filkins. Filkins later confirmed the exchanges of cash with Karzai himself, who called the allegation defamation even as he admitted it was true.

But what exactly does the exchange of cash mean?

Iran has long been involved in post-Taliban Afghanistan. As Amb. James Dobbins recounts in his section of the U.S. Institute of Peace’s Iran Primer, which was also published at Tehran Bureau, Iran’s relationship with the Northern Alliance allowed the December 2001 Bonn Conference to end successfully with the creation of an Afghani government. It was also Iran, says Dobbins, who represented the U.S. at the conference, and suggested adding language about elections to the interim Afghan constitution created in Bonn.

Most analysts seem to agree that the “bags of cash” pseudo-scandal only reinforces the notion that Iran and the U.S. share an interest in a stable Afghanistan, or at worst, that the cash handed over pales in comparison to what the U.S. throws around with Karzai unlikely to be beholden to Iranian demands.

“Worries about geopolitical bogeymen can overwhelm good sense,” writes Foreign Policy‘s Steve LeVine on his blog about oil geopolitics. “Just who is Tehran endangering by keeping Karzai lubricated with pocket change? For one, the fellows U.S. troops are fighting: the Taliban.”

“Today’s alarmism is partly over Karzai’s use of some of the Iran money to buy off Taliban leaders. To which one can rightly reply, So what? The strategic payoff is how power operates in Afghanistan,” he adds.

Michigan professor Juan Cole blogs that the revelation underscores several realities, among them “that the US and Iran are de facto allies in Afghanistan (in fact both of them are deeply opposed to the Taliban and their backers among hard line cells of the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence).”

“US military spokesmen have sometimes attempted to make a case that Iran is helping the hyper-Sunni, Shiite-killing, anti-Karzai Taliban, which is not very likely to be true or at least not on a significant scale,” he continues. “The revelations of Tehran’s support for Karzai give credence to Iranian officials’ claims of having been helpful to NATO, since they both want Karzai to succeed.”

Even Ann Marlowe, a visiting fellow at the neoconservative Hudson Institute, doesn’t think the revelation is a big deal, despite underscoring the Karzai’s “venality”: “On the bright side, the Iranian money probably doesn’t influence Mr. Karzai’s policy or Afghan actions any more than, say, our money does,” she writes on a New York Times online symposium on the subject. “The Afghan president has always had a ‘strategy of tactics,’ playing one powerbroker off against another to make sure he stays afloat.”

Thought she concludes that the money might be intended to hasten a U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, Marlowe acknowledges the ‘bags of money’ don’t pose a great threat to the United States: “The bogyman of Iranian influence in Afghanistan is overhyped. The Iranians have every interest in a relatively stable neighbor.”

This is just about the same view as neoconservative Council on Foreign Relations scholar Max Boot, who writes in Commentary: “These cash payments hardly mean that Karzai is a dupe of Iran. He gets much more money and support from the U.S. than from the Iranians, and he knows that.”

“In a way, what the Iranians are doing, while undoubtedly cynical, is not that far removed from conventional foreign-aid programs run by the U.S., Britain, and other powers that also seek to curry influence with their donations,” Boot notes. He does, however, have concerns that the Iran-Karzai relationship is an indication of what is to come for Afghanistan should the U.S. “leave prematurely.”

So there you have it. Not much on the left, not much on the right. The “bags of cash” scandal has ended up being little more than the rare confirmation of business as usual.

]]>