Yesterday, Gary Samore, president of United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI), published a column on the website of the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) arguing that even if talks between the P5+1 and Iran collapse, “Iran’s ability to produce nuclear weapons in the near term is severely constrained by political and technical factors.”

But Samore seems not to have contacted his office with that sensible sounding message. “It’s time to come down like a ton of bricks on this regime,” Gabriel Pedreira, communications director of UANI, told The Algemeiner, a US Jewish news outlet, on the same day. “We want an economic blockade if real change doesn’t come about. We haven’t seen a single concession from the Iranians, nor has even one centrifuge been destroyed,” said Pedreira.

That’s not what Samore, Pedreira’s boss, wrote. “Despite the impasse over the scale and scope of Iran’s enrichment program, the negotiators have made progress on several other issues, such as converting the Fordow enrichment facility to a research and development facility and converting the Arak heavy water research reactor to produce less plutonium,” said Samore.

And as for Pedreira’s argument that an “economic blockade” would be helpful? Samore acknowledged that a new interim agreement, presumably to be considered if the P5+1 and Iran are unable to meet the November 24 deadline for a comprehensive agreement, would be “resisted by some in Iran” if it is perceived that “it gives away too much nuclear capability without getting enough sanctions relief in return.”

In other words, an “economic blockade,” as Pedreira puts it, would give Iran’s hardliners ammunition to oppose a new interim agreement, which might be exactly what UANI wants.

The organization expressed “disappointment” with the November 2013 Joint Plan of Action, complaining that the agreement “provides disproportionate sanctions relief to Iran,” and has consistently opposed rollback of sanctions as part of an interim deal.

Indeed, both Mark Wallace, UANI’s CEO, and UANI’s mysterious benefactor, billionaire Thomas Kaplan, have expressed more hardline views than Samore, who served in the Obama administration as the president’s Coordinator for Arms Control and Weapons of Mass Destruction until last year.

But the divergence between Samore’s column, in which he is ID’d with his Belfer Center affiliation instead of UANI, and UANI’s contradictory statements the same day, raises questions about how much leadership Samore is offering to the organization and whether his role is more than purely ceremonial. Either way, Samore should probably phone his (UANI) office.

This article was published by The Nation on Sept. 30 and was reprinted here with permission. Copyright The Nation.

]]>By Robert E. Hunter

The devil is in the details. This cliché is already being invoked regarding the deal concluded this past weekend between Iran and the so-called P5+1 – the permanent members of the UN Security Council, plus Germany, along with the European Union’s High Representative, Baroness Ashton.

Devil and details, [...]]]>

By Robert E. Hunter

The devil is in the details. This cliché is already being invoked regarding the deal concluded this past weekend between Iran and the so-called P5+1 – the permanent members of the UN Security Council, plus Germany, along with the European Union’s High Representative, Baroness Ashton.

Devil and details, yes; but if there is such a thing, the “angel” is in the “big picture,” the fact of the agreement itself – interim, certainly; flawed, perhaps; but a basic break with the past, come-what-may. It will now become much harder for Iran to get the bomb, even if it were hell-bent on doing so. The risk of war has plummeted. Israel is safer – along with the rest of the region and the world — even as Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu denies that fact.

This is the end of the Cold War with Iran, (accurately) defined as a state when it is not possible to distinguish between what is negotiable and what is not. Going back to that parlous state would require a major act of Iranian bad faith, perfidy, or aggression, not at all in its self-interest.

In the last few days, the Middle East has become different from what it was before. Indeed, that happened, if one needs to denote “moments of history,” when President Barack Obama picked up the phone to call Iran’s President, Hassan Rouhani, in the latter’s limousine on the way to Kennedy Airport.

Even that moment was months in the making. But psychologically it set in train a sequence of events that is causing an earthquake in the region. And like any good earthquake, the extent, the impact, and even the direction it travels will not be clear for some time. But one thing is clear: much is now different, and despite serious down-side risks, that can be positive if people in power will make it so. As said by John Kennedy, the 50th anniversary of whose assassination also came this past week, “Our problems are man-made, therefore they may be solved by man.”

The struggle with Iran has never been just about “the bomb.” Even putting aside the question whether Iran’s insistence on having a domestic nuclear energy program would ineluctably morph into a nuclear weapons capability (or threshold capability, a “screwdriver’s turn” away from a weapon), Iran has posed a problem for the Middle East, many of its neighbors, and outsiders in the West ever since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. That turned Iran from being a supporter of Western, especially American, interests – a so-called “regional influential” – to being a challenger of US hegemony, the more-or-less accepted predominance of Sunnis over Shiites in the heart of the Middle East, and the comfort level of close US partners among Arab oil-producing states and Israel. That all happened well before Iran’s nuclear program became an issue.

Led by the United States, countries challenged by the Ayatollah Khomeini’s revolution fostered a policy of containing Iran. It included diplomatic isolation, the introduction of economic sanctions, US support – some covert, some open – for Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in its war against Iran, and US buttressing of the military security of its regional partners, along with the plentiful supply of Western armaments. There have also been widespread reports of external efforts to destabilize Iran, along with a US predilection, when not also a formal policy, for regime change in Iran, a goal which continues to have its adherents. For example, see here.

Why Iran has now decided to negotiate seriously about its nuclear program will be long debated and will be variously ascribed to swingeing economic sanctions that have increased pressures by average Iranians on their government to do what is needed to get them lifted; to progressive loss of popular support for the mullah-led regime and a “mellowing” of ideology – factors analogous to the crumbling of Soviet and East European communism two decades ago; and to the election of an Iranian president with an agenda different from his predecessor – blessed, one has to emphasize, by the Supreme Leader for reasons he has not revealed.

The current state of possibilities was helped immeasurably by a US administration that has itself been prepared to negotiate seriously, unlike its two predecessors, from the time a decade ago when Iran put a positive offer on the table that went unanswered – as Secretary of State John Kerry noted in early Sunday morning (Geneva time) commentary.

At heart, what has happened in the last two months is that Iran is now back “in play” in the region and is beginning the march toward resuming a role in the international community – slow perhaps, abortive perhaps, but for now pointed in that direction. Assuming that the issue of Iran’s nuclear program can be dealt with successfully – a big “assuming” — that is clearly in US interests. While it is much too soon to “count chickens,” that could lead toward renewed US-Iranian cooperation, tacit or explicit, over Afghanistan, where complementary interests led Iran to support the US overthrow of the Taliban regime in 2001. The possibility of Iran’s potentially no longer being a pariah state could lead it to value stability in Iraq over the pursuit of major influence there, which itself is problematic, given historic tensions between the two countries that Shia co-fraternity between the leaderships in Baghdad and Teheran only partially obscures.

It is still a stretch, however, to see Iran’s working to reconcile with Israel (a quasi-ally before 1979), although Iran’s full reengagement in the outside world and especially in relations with the United States can never be completed without Iran’s reaching out to Israel (and vice versa), a feat far more difficult than the diplomacy that began to bear fruit last weekend in Geneva. And for Iran to change its posture toward Syria and Hezbollah in Lebanon would require not just alteration of Iran’s ambitions but also changes in policies by other states and groups.

Syria is both symbol and substance of the core problem of Iran’s re-emergence as a serious player in the Middle East. At one level is the slow-burning civil war between Sunnis and Shias that was reignited by the Iranian Revolution and then, when that fire began to be tamped down, by the US-led invasion of Iraq, which overthrew a Sunni minority government dominating a majority Shia population. The war in Syria is at least in part an effort by Sunni states to “right the balance.” In the process, however, Saudi Arabia in particular has been unwilling to control elements in its country that are both inspiring and arming the worst elements of Islamist extremism and which also fuel not just Al Qaeda and its ilk but also the Taliban. They have been primary sources of destabilization in several regional states and have killed American soldiers and others in Afghanistan.

At another level is the state-centered competition for influence in the region – geopolitics. This is also linked to the relationships of regional states with the West and especially the United States. In particular, Saudi Arabia and Israel each has a basic stake in their ties to, and support by, the United States; both stoutly oppose Iran’s reentry into that competition, however modest. Of course, Israel is also concerned by the continuing risk that, somehow, the US (and others) will fail to trammel Iran’s capacity to get the bomb; and also that attention will again swing back to the unresolved Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But Saudi Arabia faces no potential military threat from Iran. Indeed, to the extent it and other Arab states of the Persian Gulf face a threat or challenge from Iran, it is denominated in terms of Sunni vs. Shia, cultural and economic penetration, and the greater vibrancy of Iranian society – none of which can be dealt with by the huge quantities of modern armaments these countries have accumulated.

Further, as Iran does again become a player and moves out from under crippling sanctions, in the process attracting massive foreign investments, uncertainties regarding Iranian power and potential challenges to its neighbors will lead the latter to cleave even more closely to the United States; and the US will have to continue being a critical strategic presence in the region – its desire to “pivot” to East Asia notwithstanding.

With all these stakes, it is not surprising that several regional states are opposing the US-led opening to Iran and have already signaled a no-holds-barred campaign, including in US domestic politics, if not to scuttle what has been achieved so far, at least to limit US (and P5+1) negotiating flexibility. (Iranian hard-liners will also be working to undercut President Rouhani.) Israel and others can rightly ask that the US not fall for a “sucker’s deal,” though, as Secretary Kerry correctly stated, “We are not blind, and I don’t think we’re stupid.” But they are also worried that they will lose their long-unchallenged preeminence in Washington and with Western business interests. This is not Washington’s problem. Indeed, from Afghanistan to Iraq to Syria and even to Israeli-Palestinian relations, drawing Iran constructively into the outside world – if that can be done and done safely – is very much in US interests.

Even as things stand now, at an early stage in moving beyond cold war with Iran, President Obama has earned his Nobel Peace Prize.

]]>by Mark N. Katz

Why has Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov made his dramatic proposal for the Syrian government to not only put its chemical weapons under international control, but also destroy them? There are two possibilities.

This could be a Russian attempt to avert the US military strike on Syria that [...]]]>

by Mark N. Katz

Why has Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov made his dramatic proposal for the Syrian government to not only put its chemical weapons under international control, but also destroy them? There are two possibilities.

This could be a Russian attempt to avert the US military strike on Syria that President Obama called for in response to the Syrian government’s use of chemical weapons against so many of its own citizens on Aug. 21. Fully understanding that support for such a move is weak within Congress, among America’s allies, and in Western public opinion, Moscow hopes that its diplomatic initiative will prevent a strike that would weaken the Assad regime’s ability to defeat its opponents with conventional weapons.

In light of both Soviet and post-Soviet Russian diplomatic efforts, the chance that such cynical motives underlie Lavrov’s initiative cannot be ruled out. But there is another possibility. Considering that Moscow has heretofore denied that Damascus has or ever would use chemical weapons, Lavrov’s proposal could be seen as a stark warning to Assad: either surrender your chemical weapons to international control and destruction, or Moscow will do nothing to defend you against an American strike.

The truth is that these two possible motives are not mutually exclusive. Russia could be simultaneously trying to rally forces in the West wishing to prevent a strike and warning Damascus that its use of chemical weapons last month went too far — even for Moscow.

One thing, though, is certain: Lavrov only made this proposal because Obama has issued a credible threat to strike Syria.

Bashar al-Assad may have accepted the Lavrov proposal because he understands that Saddam Hussein’s non-compliance with the UN Security Council’s weapons of mass destruction inspection program in 2002-03 was seized upon by the Bush administration as justification for a US-led invasion. It is doubtful, though, that Assad will give up his chemical weapons even at Moscow’s behest if he does not feel the threat of a debilitating American attack (even if it’s not an outright invasion).

The immediate reaction of both the Senate and President Obama to the Lavrov proposal has been talk of delaying any such attack — which is exactly what Moscow and Damascus wanted. For the US to incentivize Assad to actually surrender his chemical weapons Washington must maintain the threat of a large-scale attack against him unless Assad complies immediately.

]]>by Robert E. Hunter

Now, after careful deliberation, I have decided that the United States should take military action against Syrian regime targets. This would not be an open-ended intervention. We would not put boots on the ground. Instead, our action would be designed to be limited in duration and scope.

I’ve [...]]]>

by Robert E. Hunter

Now, after careful deliberation, I have decided that the United States should take military action against Syrian regime targets. This would not be an open-ended intervention. We would not put boots on the ground. Instead, our action would be designed to be limited in duration and scope.

I’ve made a second decision: I will seek authorization for the use of force from the American people’s representatives in Congress….this morning, I spoke with all four congressional leaders, and they’ve agreed to schedule a debate and then a vote as soon as Congress comes back into session.

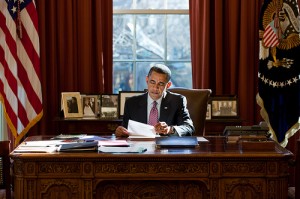

–President Barack Obama, August 31, 2013

President Barack Obama’s announcement this weekend that he has “decided that the United States should take military action against Syrian regime targets” is remarkable for many reasons, in particular because he coupled it with a commitment to “seek authorization for the use of force from…Congress.”

The first remarkable element is that he has already taken the decision to strike before fully engaging Congress, instead of the usual practice of reserving judgment on possible military action until that process is complete. This immediately begs the question “What if Congress balks?” Does the president go ahead anyway? And if Congress turns him down — after all, he is not “consulting” but “seek[ing] authorization” — does that affect his (and America’s) credibility, as the author of the “red line” against the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian government? Proponents of a military strike are already making that point, although, in this writer’ judgment, it is grossly overdrawn, and no one who wishes us ill should put much weight on this proposition.

The best counterargument is that, at a time when the UN and others are still assembling evidence on the use of chemical weapons (undeniable) and “who did it” (probably the Syrian government), waiting awhile is not a bad thing. Obama covered the point about risk of delay by citing the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff “…that our capacity to execute this mission is not time-sensitive; it will be effective tomorrow, or next week, or one month from now.” Taking the time “to be sure” is thus useful; as is the value in trying to build support in Congress, especially given the clarity of memory about the process leading up to the US-led invasion of Iraq a decade ago, when the intelligence “books” were “cooked” by Bush administration officials, as well as by the British government.

The second remarkable element is that the president did not ask Congress to reconvene in Washington in the next day or two, but is content to wait until members return on September 9th. This provides time for the administration to build its case on Capitol Hill, supporting a decision the president says he has already taken; but it also risks diminishing the perceived sense of importance that his team, notably Secretary of State John Kerry, here and here, has been building about the enormity of what has been done.

A related factor is that the United States will not be responding to a direct assault on the United States or its people abroad, civilian or military, and the case for America’s taking the lead is less about our interests than what, at other times, has been called America’s role as the “indispensable nation.” As has been made clear by all and sundry, if the US does not act, no one else will shoulder the responsibility. But this lack of a direct threat to the nation heightens the president’s need to make his case that the US must take the lead.

The need to make the case to Congress was hammered home by the British parliament’s rejection of a UK role in any attack on Syria, despite the lead taken by Prime Minister David Cameron and Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary William Hague in pressing for military action — and thus helping to “box in” the US president. No doubt, what Parliament did influenced Obama’s decision to get the US Congress firmly on record in supporting his decision to act.

A third remarkable element, though not surprising, is that the administration has apparently given up on the United Nations. To be sure, Russia and China would veto in the Security Council any resolution calling for force; but it would have been common practice — and may yet be done — for the US to apply to the recognized court of world opinion by at least trying, loud and long, to establish an international legal basis for military action, even it fails to achieve UN agreement. There is precedent for this approach, notably over Kosovo in 1998, where the UN failed to act (threat of vetoes), but the US at least made a “college try” and demonstrated the point it sought to make. This made it easier for individual NATO allies to adopt the fudge that each member state could decide for itself the legal basis on which it was prepared to act.

But the most remarkable element of the President’s statement is the likely precedent he is setting in terms of engaging Congress in decisions about the use of force, not just through “consultations,” but in formal authorization. This gets into complex constitutional and legal territory, and will lead many in Congress (and elsewhere) to expect Obama — and his successors — to show such deference to Congress in the future, as, indeed, many members of Congress regularly demand.

But seeking authorization for the use of force from Congress as opposed to conducting consultations has long since become the exception rather than the rule. The last formal congressional declarations of war, called for by Article One of the Constitution, were against Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary on June 4, 1942. Since then, even when Congress has been engaged, it has either been through non-binding resolutions or under the provisions of the War Powers Resolution of November 1973. That congressional effort to regain some lost ground in decisions to send US forces into harm’s way was largely a response to administration actions in the Vietnam War, especially the Tonkin Gulf Resolution of August 1964, which was actually prepared in draft before the triggering incident. The War Powers Resolution does not prevent a president from using force on his own authority, but only imposes post facto requirements for gaining congressional approval or ending US military action. In the current circumstances, military strikes of a few days’ duration, those provisions would almost certainly not come into play.

There were two basic reasons for abandoning the constitutional provision of a formal declaration of war. One was that such a declaration, once turned on, would be hard to turn off, and could lead to a demand for unconditional surrender (as with Germany and Japan in World War II), even when that would not be in the nation’s interests — notably in the Korean War. The more compelling reason for ignoring this requirement was the felt need, during the Cold War, for the president to be able to respond almost instantly to a nuclear attack on the United States or on very short order to a conventional military attack on US and allied forces in Europe.

With the Cold War now on “the ash heap of history,” this second argument should long since have fallen by the wayside, but it has not. Presidents are generally considered to have the power to commit US military forces, subject to the provisions of the War Powers Resolution, which have never been properly tested. But why? Even with the 9/11 attacks on the US homeland, the US did not respond immediately, but took time to build the necessary force and plans to overthrow the Taliban regime in Afghanistan (and, anyway, if President George W. Bush had asked on 9/12 for a declaration of war, he no doubt would have received it from Congress, very likely unanimously).

As times goes by, therefore, what President Obama said on August 29, 2013 could well be remembered less for what it will mean regarding the use of chemical weapons in Syria and more for what it implies for the reestablishment of a process of full deliberation and fully-shared responsibilities with the Congress for decisions of war-peace, as was the historic practice until 1950. This proposition will be much debated, as it should be; but if the president’s declaration does become precedent (as, in this author’s judgment, it should be, except in exceptional circumstances where a prompt military response is indeed in the national interest), he will have done an important and lasting service to the nation, including a potentially significant step in reducing the excessive militarization of US foreign policy.

There would be one added benefit: members of Congress, most of whom know little about the outside world and have not for decades had to take seriously their constitutional responsibilities for declaring war, would be required to become better-informed participants in some of the most consequential decisions the nation has to take, which, not incidentally, also involve risks to the lives of America’s fighting men and women.

Photo Credit: Truthout.org

]]>via IPS News

While some kind of U.S. military action against Syria in the coming days appears increasingly inevitable, the debate over the why and how of such an attack has grown white hot here.

On one side, hawks, who span the political spectrum, argue that President Barack Obama’s credibility [...]]]>

via IPS News

While some kind of U.S. military action against Syria in the coming days appears increasingly inevitable, the debate over the why and how of such an attack has grown white hot here.

On one side, hawks, who span the political spectrum, argue that President Barack Obama’s credibility is at stake, especially now that Secretary of State John Kerry has publicly endorsed the case that the government of President Bashar Al-Assad must have been responsible for the alleged chemical attack on a Damascus suburb that was reported to have killed hundreds of people.

Just one year ago, Obama warned that the regime’s use of such weapons would cross a “red line” and constitute a “game-changer” that would force Washington to reassess its policy of not providing direct military aid to rebels and of avoiding military action of its own.

After U.S. intelligence confirmed earlier this year that government forces had on several occasions used limited quantities of chemical weapons against insurgents, the administration said it would begin providing arms to opposition forces, although rebels complain that nothing has yet materialised.

The hawks have further argued that U.S. military action is also necessary to demonstrate that the most deadly use of chemical weapons since the 1988 Halabja massacre by Iraqi forces against the Kurdish population there – a use of which the US. was fully aware but did not denounce at the time – will not go unpunished.

Military action should be “sufficiently large that it would underscore the message that chemical weapons as a weapon of mass destruction simply cannot be used with impunity,” said Richard Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), told reporters in a teleconference Monday. “The audience here is not just the Syrian government.”

While the hawks, whose position is strongly backed by the governments of Britain, France, Gulf Arab kingdoms and Israel, clearly have the wind at their backs, the doves have not given up.

Remembering Iraq

Recalling the mistakes and distortions of U.S. intelligence in the run-up to the 2003 Iraq War, some argue that the administration is being too hasty in blaming the Syrian government.

If it waits until United Nations inspectors, who visited the site of the alleged attack Monday, complete their work, the United States could at least persuade other governments that Washington is not short-circuiting a multilateral process as it did in Iraq.

Many also note that military action could launch an escalation that Washington will not necessarily be able to control, as noted by a prominent neo-conservative hawk, Eliot Cohen, in Monday’s Washington Post.

“Chess players who think one move ahead usually lose; so do presidents who think they can launch a day or two of strikes and then walk away with a win,” wrote Cohen, who served as counsellor to former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. “The other side, not we, gets to decide when it ends.”

“What if [Obama] hurls cruise missiles at a few key targets, and Assad does nothing and says, ‘I’m still winning.’ What do you then?” asked Col. Lawrence Wilkerson (ret.), who served for 16 years as chief of staff to former Secretary of State Colin Powell. “Do you automatically escalate and go up to a no-fly zone and the challenges that entails, and what then if that doesn’t get [Assad's] attention?

“This is fraught with tar-babiness,” he told IPS in a reference to an African-American folk fable about how Br’er Rabbit becomes stuck to a doll made of tar. “You stick in your hand, and you can’t get it out, so you then you stick in your other hand, and pretty soon you’re all tangled up all this mess – and for what?”

“Certainly there are more vital interests in Iran than in Syria,” he added. “You can’t negotiate with Iran if you start bombing Syria,” he said, a point echoed by the head of the National Iranian American Council, Trita Parsi.

“There is a real opportunity for successful diplomacy on the Iranian nuclear issue, but that opportunity will either be completely spoiled or undermined if the U.S. intervention in Syria puts the U.S. and Iran in direct combat with each other,” he told IPS. Humanitarian concerns and U.S. credibility should also be taken into account when considering intervention, he said.

Remembering Kosovo

Still, the likelihood of military action – almost certainly through the use of airpower since even the most aggressive hawks, such as Republican Senators John McCain and Lindsay Graham, have ruled out the commitment of ground troops – is being increasingly taken for granted here.

Lingering questions include whether Washington will first ask the United Nations Security Council to approve military action, despite the strong belief here that Russia, Assad’s most important international supporter and arms supplier, and China would veto such a resolution.

“Every time we bypass the council for fear of a Russian or Chinese veto, we drive a stake into the heart of collective security,” noted Daryl Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association. “Long-term, that’s not in our interest.”

But the hawks, both inside the administration and out, are urging Obama to follow the precedent of NATO’s air campaign in 1999 against Serbia during the Kosovo War. In that case, President Bill Clinton ignored the U.N. and persuaded his NATO allies to endorse military intervention on humanitarian grounds.

The 78-day air war ultimately persuaded Yugoslav President Milosovic to withdraw his troops from most of Kosovo province, but not before NATO forces threatened to deploy ground troops, a threat that the Obama administration would very much like to avoid in the case of Syria.

While the administration is considered most likely to carry out “stand-off” strikes by cruise missiles launched from outside Syria’s territory to avoid its more formidable air-defence system and thus minimise the risk to U.S. pilots, there remains considerable debate as to what should be included in the target list.

Some hawks, including McCain and Graham, have called not only for Washington to bomb Syrian airfields and destroy its fleet of warplanes and helicopter and ballistic capabilities, but also to establish no-fly zones and safe areas for civilians and rebel forces to tilt the balance of power decisively against the Assad government. Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states, led by Saudi Arabia, have urged the same.

But others oppose such far-reaching measures, noting that the armed opposition appears increasingly dominated by radical Islamists, some of them affiliated with Al Qaeda, and that the aim of any military intervention should be not only to deter the future use of chemical weapons but also to prod Assad and the more moderate opposition forces into negotiations, as jointly proposed this spring by Moscow and Washington. In their view, any intervention should be more limited so as not to provoke Assad into escalating the conflict.

Photo: Secretary of State John Kerry delivers remarks on Syria at the Department of State in Washington, DC, on August 26, 2013. Credit: State Department

]]>by Mitchell Plitnick

US Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel may have insisted that the latest sale of US arms to Israel sent a strong message to Iran, but the actual message was a bit more restrained. Hagel made a point of emphasizing that the arms sale reaffirmed the close ties between [...]]]>

by Mitchell Plitnick

US Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel may have insisted that the latest sale of US arms to Israel sent a strong message to Iran, but the actual message was a bit more restrained. Hagel made a point of emphasizing that the arms sale reaffirmed the close ties between the nations and repeated the Obama Administration’s mantra that Israel has the right to defend itself. The actual sale, though, gave the US another lever of control over a potential Israeli attack.

For Israel, the sale was a double-edged sword. The new equipment from the US does make it easier for Israel to attack Iran. Anti-radiation missiles disrupt anti-aircraft systems, and the new refueling jets modernize and expand Israel’s existing arsenal of such planes.

What they don’t do is give Israel the means to carry out an attack on Iran’s key nuclear facility at Fordo. For that, Israel needs the prize it has been seeking from the US: the new Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP), a “super bunker-buster” bomb weighing fifteen tons that’s capable of penetrating ten times as much concrete as previous models. With the Fordo site located some 300 feet underground, the MOP is the only bomb that might be able to impact the facility.

It is by no means certain that even the MOP could knock the Fordo facility out, but without that bomb, Israel cannot realistically try, short of a massive ground invasion. And even with the bomb itself, Israel would still need a plane to deliver the 15-ton explosive. Only a B-2 bomber can do that operationally and Israel currently does not have one.

The message being sent to Israel becomes clearer in light of an interesting event in the Senate on April 17. Senate Resolution 65 was an AIPAC-Sponsored bill that included a clause which committed the United States to supporting Israel if it attacked Iran. Usually, such AIPAC bills slide through the Senate and quickly reach an up or down vote on the floor. This one was marked up in the Foreign Relations Committee.

The markup was significant. Though it still commits the US to supporting Israel against Iran, it is not a simple green light for an Israeli attack with a rubber stamp on US involvement. It refers to legitimate self-defense, rather than just any Israeli decision to attack. The US can decide whether an Israeli act constitutes “legitimate self-defense”. The bill also makes clear that such defense refers only to Iranian nuclear targets. The markup also clarifies that any US support for an Israeli attack must conform to US law, including further Congressional authorization for any US action.

It’s still a problematic bill for many reasons, but it doesn’t create an automatic path for Israel to force the United States into a war with Iran. The fact that this AIPAC bill even went to a markup is unusual and says a lot. Combined with the public refusal to sell Israel the MOP — which gives the strong impression that the US is not even considering such a sale — an image of an Obama Administration determined to have a much firmer grip on its Iran policy during its second term emerges. Previously they felt too easily pressured by Israel’s and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s grip on Congress and public opinion.

The US did enhance Israel’s ability to attack Iran, but it continues to guard the key to making such a mission successful in terms of setting back the Iranian nuclear program. In this way, the Obama Administration has stood by its principle that Israel has the right to defend itself, while maintaining its control over critical decisions regarding Iran. And Congress did not end up thwarting the administration’s designs.

By making it clear that Israel is free to make its own decisions — and that the US will also do so — Obama hopes to blunt Netanyahu’s ability to mount the sort of pressure he did last time. Given that Israel seems to be publicly playing along with these moves, the plan may be working, at least for now.

While a lot of attention has been paid to the continuing US refusal to provide Israel with the massive bunker buster bomb, much of the strategy at play in this sale was revealed in a piece of equipment Israel was able to buy. The V-22 Osprey combines the speed and range of a plane with the vertical maneuverability of a helicopter. Its main use is as a personnel and supplies carrier, though it can also be equipped with surveillance devices.

Israel is the first country the US has sold the V-22 to. Its ability to land almost anywhere it can fit and hover over a given point combines with its range to significantly increase areas in which Israel can consider infiltration operations. It’s possible that some sort of commando operation into Iran could be augmented by the V-22, but it wouldn’t be a direct flight; Iran lies at the extreme edge of the V-22’s range. It would have to be carried there on a ship.

More likely, the V-22 is meant for use in the more immediate neighborhood. It will enable Israel, according to one anonymous Israeli colonel, to “…be able to carry out operations that we never imagined that one of our planes could execute. If we purchase the plane, our ranges of activity will dramatically change and we’ll be able to reach points we’ve never even dreamed of.”

The V-22 could be used to get commandos in and out of areas quickly, enabling Israel to strike specific targets deep inside Arab countries. It would enhance their ability to launch operations at selected militant camps or people and get their own soldiers in and out quickly.

Although the V-22 is likely to be sold to other US allies soon, selling it to Israel before any other country was clearly meant to further the charm offensive that President Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry have been pushing with their visits to the region recently. But underlying that is a tie-in with the efforts to mend the breach between Israel and Turkey.

The hope seems to be that Turkey and Israel can work together to enhance stability in the region as the dominant military powers. That is a bit of a stretch, it’s true, but the US wants to scale back its direct involvement in the region, and this is one way of doing that. It could work. In the worst and more likely case, the US will have enhanced Israel’s ability to strike at unfriendly groups within increasingly tumultuous Arab countries. That keeps Netanyahu happy and is the sort of activity that the US has generally wanted Israel to engage in, despite sometimes explosive consequences.

Photo: Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel gives his opening remarks during a joint media availability with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu before a meeting in Jerusalem, Israel, on April 23, 2013. DoD photo by Erin A. Kirk-Cuomo.

]]>By Robert E. Hunter

As President Obama assembles his new national security team, all eyes are on the four top jobs. These choices obviously matter, to ensure effective US diplomacy (Secretary of State); relevant but reduced military power (Secretary of Defense); an intelligence function attuned to understanding the world rather than [...]]]>

By Robert E. Hunter

As President Obama assembles his new national security team, all eyes are on the four top jobs. These choices obviously matter, to ensure effective US diplomacy (Secretary of State); relevant but reduced military power (Secretary of Defense); an intelligence function attuned to understanding the world rather than fighting the nation’s wars (CIA Director); and a National Security Advisor who asks searching questions and gets the team to work together.

As President Obama assembles his new national security team, all eyes are on the four top jobs. These choices obviously matter, to ensure effective US diplomacy (Secretary of State); relevant but reduced military power (Secretary of Defense); an intelligence function attuned to understanding the world rather than fighting the nation’s wars (CIA Director); and a National Security Advisor who asks searching questions and gets the team to work together.

Yet in fact these top four appointments hardly matter more than what the president and his Cabinet do to marshal a total team, top-to-bottom, that’s able to do the nation’s business abroad. Judging from recent history, this is unlikely to happen.

In reality, most policy is “made,” and certainly both shaped for decision and later carried into action, not at the highest levels, but within the next several layers down. Here, the president and his advisers need to pay as much attention to putting in place people who can do the job “in the ranks” as at the Cabinet level. Yet most sub-cabinet appointments will likely go to individuals who served in the first Obama administration, whether they have done well or poorly — “promotion from within;” who served in the recent presidential campaign (although campaign and governance skills are decidedly different); or who have personal connections with the new Cabinet members, where “comfort level” is often prized over capacity.

Unlike every other Western government, the US professional Foreign Service usually gains admittance to the higher reaches of government only episodically. That means the skills of governing have to be learned on the job by new entrants to State or the civilian side of the Pentagon. It also tends to limit the access of people who have “been there and done that” for years, both abroad and in Washington, in regard to many of the most complex challenges to the US.

The good news is that, by the second term, presidents who are foreign policy tyros when they first enter the Oval Office — and only two recent new presidents, Richard Nixon and George H.W. Bush, have not been tyros because they mastered the national security trade as vice president — have learned a lot about the true requirements of being commander-in-chief.

There is also bad news: since the end of the Cold War, the US has disarmed itself in the capacity to do hard strategic analysis and policy integration even more than it reduced the size of its military. Confrontation with the Soviet Union spawned a major industry in strategic thought, from the 1950s until the Berlin Wall fell, and the afterglow served the nation well for a time afterward — notably in George H.W. Bush’s managing the effects of the Soviet Union’s collapse, fostering Germany’s unification, and promulgating a grand strategy of a “Europe whole and free and at peace.”

Since then, no president has placed priority on hiring and using effectively people genuinely able to “think strategically” and relate the world’s apples to its oranges. In the Holiday from History before 9/11, that did not much matter; now it matters critically. It begins with clear understanding that the US economy is Thing One for national security; and that the imbalance between military and non-military instruments (the dollar ratio is still 17:1) damages the required integration of US efforts abroad, as underscored in both Iraq and Afghanistan. US engagement in North Africa-the Near East-the Persian Gulf-Southwest Asia is still pursued as though these are four only tangentially-related areas, carved up bureaucratically into disparate areas by both State and Defense, rather than as an interconnected region that has to be met and mastered together. Remarkably, none of the last three presidents has engaged a top-flight group of people, from inside and outside government, able to do just that. The recurring inadequacies of US policies are evidence enough.

It is 32 years since Zbigniew Brezezinski left office; 36 for Henry Kissinger — the last two masters of strategic thinking in the US government. Yet while there are available at least several first-rate strategic thinkers and integrators of policy, none serves in the administration.

It will be a year or more before President Obama can be judged a successful foreign policy president; but he can set a course for failure in the next few weeks, unless he chooses his full team wisely and includes at least one person (preferably several) who can provide the strategic insight, analytical skills, and translation into integrated policies he and the nation must have.

– Robert Hunter was ambassador to NATO in the Clinton Administration and until recently was director of the Center for Transatlantic Security Studies at the National Defense University.

]]>