by James A. Russell

Russia’s storming of the Ukrainian naval base in Crimea just as Iran and world powers wrapped up another round of negotiations in Vienna earlier this week represent seemingly contradictory bookends to a world that some believe is spinning out of control.

It’s hard not to argue that the [...]]]>

by James A. Russell

Russia’s storming of the Ukrainian naval base in Crimea just as Iran and world powers wrapped up another round of negotiations in Vienna earlier this week represent seemingly contradictory bookends to a world that some believe is spinning out of control.

It’s hard not to argue that the world seems a bit trigger-happy these days. Vladimir Putin’s Russian mafia thugs armed with weapons bought with oil money calmly annex the Crimea. Chinese warships ominously circle obscure shoals in the Western Pacific as Japan and other countries look on nervously. Israel and Hezbollah appear eager to settle scores and start another war in Lebanon. Syria and Libya continue their descent into a medieval-like state of nature as the world looks on not quite knowing what to do.

The icing on the cake is outgoing Afghanistan President Hamid Karzai’s telling the United States to get stuffed and leave his country — after we’ve spent billions dollars of borrowed money and suffered thousands of casualties over 13 years propping up his corrupt kleptocracy. Karzai and his cronies are laughing all the way to their secret Swiss banks with their pockets stuffed full of US taxpayer dollars. Why the United States thinks it needs to maintain a military presence in Afghanistan remains a mystery — but that’s another story altogether.

In the United States, noted foreign policy experts like Senator John McCain, Lindsey Graham and Condoleeza Rice have greeted these developments with howls of protest and with a call to arms to reassert America’s global leadership to tame a world that looks like it’s spinning out of control. They appear to believe that we should somehow use force or the threat of force as an instrument to restore order. Never mind that these commentators have exercised uniformly bad judgment on nearly all the major foreign policy issues of the last decade.

In the United States, noted foreign policy experts like Senator John McCain, Lindsey Graham and Condoleeza Rice have greeted these developments with howls of protest and with a call to arms to reassert America’s global leadership to tame a world that looks like it’s spinning out of control. They appear to believe that we should somehow use force or the threat of force as an instrument to restore order. Never mind that these commentators have exercised uniformly bad judgment on nearly all the major foreign policy issues of the last decade.

The protests of these commentators notwithstanding, however, it is worth engaging in a debate about what all these events really mean; whether they are somehow linked and perhaps emblematic of a more important structural shift in international politics towards a more warlike environment. For the United States, these developments come as the Obama administration sensibly tries to take the country’s military off a permanent war-footing and slow the growth in the defense budget — a budget that will still see the United States spend more on its military than most of the rest of the world combined.

The first issue is whether the events in Crimea are emblematic of a global system in which developed states may reconsider the basic calculus that has governed decision-making since World War II — that going to war doesn’t pay. Putin may have correctly calculated that the West doesn’t care enough about Crimea to militarily stop Russia, but would the same calculus apply to Moldova, Poland, or some part of Eastern Europe? Similarly, would the Central Committee in Beijing risk a wider war in the Pacific over the bits of rocks in the South China Sea that are claimed by various countries?

While we can’t know the answer to these questions, the political leadership of both Russia and China clearly would face significant political, economic, and military costs in choosing to exercise force in a dispute in which the world’s developed states could not or would not back down. These considerations remain a powerful deterrent to a resumption of war between the developed states, events in Crimea notwithstanding– although miscalculations by foolhardy leaders are always a possibility. Putin could have chosen some other piece of real estate that might have led to a different reaction by the West, but it seems unlikely.

The second kind of inter-state dispute troubling the system are those between countries/actors that have a healthy dislike for one another. Clearly, the most dangerous of these situations is the relationship between India and Pakistan — two nuclear-armed states that have been exchanging fire directly and indirectly for much of the last half century. By the same token, however, there is really nothing new in this dispute that has remained a constant since both states were created after Britain’s departure from the subcontinent.

Similarly, the situation in the Middle East stemming from Israel’s still unfinished wars of independence remains a constant source of regional instability. Maybe one day, Israel and its neighbors will finally decide on a set of agreeable borders, but until they do we can all expect them to resort to occasional violence until the issue is settled. Regrettably, neither Israel nor its neighbors shows any real interest in peaceful accommodation.

The third kind of war is the intra-national conflicts like those in Syria, the Congo, and Libya that some believe is emblematic of a more general slide into a global state-of-nature Hobbesian world in which the weak perish and the strong survive. If this is the case, what if anything can be done about it?

Here again, however, we have to wonder what if anything is new with these wars. As much as we might not like it, internal political evolution in developing states can and often does turn violent until winners emerge. The West’s own evolution in Europe took hundreds of years of bloodshed until winners emerged and eventually established political systems capable of resolving disputes peacefully through politics and national institutions. The chaos in places like Syria, the Congo, Libya, and Afghanistan has actually been the norm of international politics over much of the last century — not the exception.

This returns us to the other bookend cited at the outset of this piece — the reconvened negotiations in Vienna that are attempting to resolve the standoff between Iran and the international community. These meetings point to perhaps the most significant change in the international system over the last century that has seen global institutions emerge as mechanisms to control state behavior through an incentive structure that discourages war and encourages compliance with generally accepted behavioral norms.

These institutions, such as the United Nations, and their supporting regulatory structures like the International Atomic Energy Agency have helped establish new behavioral norms and impose costs on states that do not comply with the norms. While we cannot be certain of what caused Iran to seek a negotiated solution to its standoff with the international community over its nuclear program, it is clear that the international community has imposed significant economic costs on Iran over the last eight years of ever-tightening sanctions.

Similarly, that same set of global institutions and regulatory regimes supported by the United States will almost certainly impose sanctions that will increase the costs of Putin’s violation of international norms in Russia’s seizure of Crimea. Those costs will build up over time, just as they have for Iran and other states like North Korea that find themselves outside of the general global political and economic system. As Iran has discovered, and as Russia will also discover — it’s an expensive and arguably unsustainable proposition to be the object of international obloquy.

For those hawks arguing for a more militarized US response to these disparate events, it’s worth returning to George F. Kennan’s basic argument for a patient, defensive global posture. Kennan argued that inherent US and Western strength would see it through the Cold War and triumph over its weaker foes in the Kremlin. As Kennan correctly noted: we were strong, they were weaker. Time was on our side, not theirs. The world’s networked political and economic institutions only reinforce the strength of the West and those other members of the international community that choose to play by the accepted rules for peaceful global interaction.

The same holds true today. Putin’s Russia is a paper tiger that is awash in oil money but with huge structural problems. Russia’s corrupt, mafia-like dictatorship will weaken over time as it is excluded from the system of global political and economic interactions that rewards those that play by the rules and penalizes those that don’t.

As for other wars around the world in places like Syria, we need to recognize they are part of the durable disorder of global politics that cannot necessarily be managed despite the awful plight of the poor innocent civilians and children — who always bear the costs of these tragic conflicts.

We need to calm down and recognize that the international system is not becoming unglued; it is simply exhibiting immutable characteristics that have been with us for much of recorded history. We should, however, be more confident of the ability of the system (with US leadership) to police itself and avoid rash decisions that will only make these situations worse.

Photo: A Russian armoured personnel carrier in Simferopol, the provincial capital of Crimea. Credit: Zack Baddorf/IPS.

]]>by Jim Lobe

Just 11 days before the annual policy conference of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), the embattled organization got some more bad news, this time in the form of a Gallup poll suggesting that nearly ten years of effort in demonizing Iran in the U.S. public mind [...]]]>

by Jim Lobe

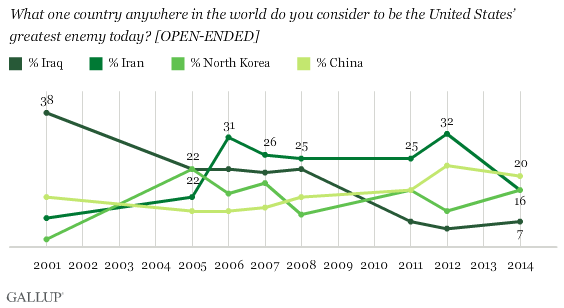

Just 11 days before the annual policy conference of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), the embattled organization got some more bad news, this time in the form of a Gallup poll suggesting that nearly ten years of effort in demonizing Iran in the U.S. public mind may be going down the drain. As Gallup noted in the lede on its analysis of the poll, “Half as many Americans view Iran as the United States’ greatest enemy today as did two years ago.”

Indeed, for the first time since 2006, according to the survey of of more than 1,000 U.S. adults, Iran is no longer considered by the U.S. public to be “the United States’ greatest enemy today.” The relative threat posed by Iran has fallen quite dramatically in just the last two years, the survey found. In 2012, an all-time high of 32 percent of respondents identified Iran as Washington’s greatest foe, significantly higher than the 22 percent who named China. Beijing has now replaced Tehran as the most frequently mentioned greatest threat.” Twenty percent of all respondents cited China, while only 16 percent — or half the percentage of respondents compared to just two years ago — named Iran (which was tied with North Korea).

This is a significant setback for the Israel lobby and AIPAC, which has made Iran the centerpiece of its lobbying activities for the past decade and more, and it should add to the consternation that many of its biggest donors (as well as members) must feel in the wake of its serial defeats on Chuck Hagel, Syria, and, most importantly, on getting new sanctions legislation against Iran last month. As its former top lobbyist, Douglas Bloomfield told me three weeks ago,

Like the old cliche about real estate, ‘Location, location, location,’ for [AIPAC], it’s been ‘Iran, Iran, Iran. Israel and the peace process is in a distant second place.

Now, of course, just as one swallow does not a summer make, one poll can’t be seen as showing a definite trend. But, as you can see from Gallup’s 2001-2014 tracking graph below, the decline in threat perception since 2012 has been remarkably sharp compared, for example, to China’s showing, which has been relatively stable. And the difference between the two nations — 20 percent versus 16 percent — is within the 4-percent margin of error. Still, the fact (brutal as it is for AIPAC) remains: Iran, while still very unpopular (only 12 percent of respondents have a favorable image of it, second in unfavorability only to North Korea), is no longer seen by an important percentage of the population as Washington’s “greatest enemy.”

Moreover, as noted by Gallup’s analysis, “[g]roups that were the most likely to view Iran as the top enemy, such as men, older Americans, and college graduates, tend to show the greatest declines” in seeing Iran as Public Enemy Number One. Younger respondents (aged 18 to 34 years) were least likely to see Iran as the greatest enemy; only nine percent, compared to 21 and 20 percent for China and North Korea, respectively. As for party affiliation, a plurality of Republicans — the party most influenced by neoconservative ideology — still see Iran as the most threatening (20 percent, versus China’s 19 percent); while 23 percent of independents named China as the greatest enemy compared to 16 percent who selected Iran. Among Democrats, 24 percent cited North Korea; only half that percentage named Iran.

Clearly, President Hassan Rouhani and his Foreign Minister Javad Zarif, who dominated U.S. news coverage of Iran during their New York visit in September, as well as progress in negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program, have made a big difference, thus vindicating Benjamin Netanyahu’s (and AIPAC’s) worst fears. No doubt growing tensions between China and its neighbors have also drawn attention away from Iran (which should help, in a somewhat perverse way, Obama’s efforts to “pivot” foreign policy resources more toward Asia), although, as noted above, concern about China has remained relatively stable over the 13 years and actually declined slightly compared to 2012.

Of course, this could also turn around in a flash given the right catalyst. A breakdown in the talks, an incident at sea, or some other unanticipated event could persuade the public that all of the rhetoric about how Iran poses the greatest threat imaginable to the United States and its allies — likely to be amplified at the Washington Convention Center, where AIPAC holds its conference early next month — could propel Tehran back up to the top of the enemies list. But, for now, it’s clear that Netanyahu, who is expected to continue — if not escalate — his aggressive denunciations against the nuclear deal and U.S.-Iranian detente when he comes here to keynote the AIPAC conference, faces a tougher challenge in persuading the American public that Iran poses the greatest threat to U.S. security than at any time since he became Prime Minister. For more on Bibi’s challenges here, read J.J. Goldberg’s editorial in the latest Forward entitled, “Benjamin Netanyahu Tells AIPAC to Put Its Head in a Noose: Pushing American Jews to Take Unpopular Stand on Iran.”

Photo: US Secretary of State John Kerry, EU Foreign Policy Chief Catherine Ashton and Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif’s meeting on the sidelines of the UNGA on Sept. 26, 2013.

]]>by Marsha B. Cohen

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, as of last week, planned on hitting the “refresh” button on the Iranian threat to Israel and the world, juxtaposing the callow grimace of North Korean dictator Kim Jong-Un with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s ubiquitous smile.

Israeli media on Sunday — after President [...]]]>

by Marsha B. Cohen

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, as of last week, planned on hitting the “refresh” button on the Iranian threat to Israel and the world, juxtaposing the callow grimace of North Korean dictator Kim Jong-Un with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s ubiquitous smile.

Israeli media on Sunday — after President Barack Obama’s historic 15-minute phone call with Rouhani — reported Netanyahu was furiously rewriting his UN speech, “vowing to expose ‘the truth’ in the wake of Iranian President Hasan Rouhani’s recent overtures to the United States.”

“Like North Korea before it, Iran will try to remove sanctions by offering cosmetic concessions, while preserving its ability to rapidly build a nuclear weapon at a time of its choosing,” Netanyahu’s office said in a statement explaining the Israeli delegation’s decision to boycott Rouhani’s address last week to the UN General Assembly (UNGA).

Can Netanyahu successfully revive the Bush administration’s lumping together of Iran with North Korea into a new “axis of evil”? He’s done it before, and, according to numerous reports, he’s certainly going to try again on Tuesday. At least this was the plan prior to the phone conversation between Obama and Rouhani on Friday, about which Netanyahu has not commented on and banned his government’s ministers, staff and Israel’s ambassadors from discussing. Israel’s Channel 2 reported on Saturday night that Israel was advised in advance that the phone call would take place, but “there was no advance coordination of positions” between Israel and the US on the content of the talk, according to the Times of Israel.

Netanyahu’s own UNGA speech on Oct. 1 is expected to chronicle the failure of diplomacy to deter North Korea’s development of nuclear weapons, arguing that North Korea’s case demonstrates the futility of diplomatic engagement with Iran. The Israeli daily Israel Hayom reports:

Netanyahu will try to teach the Americans a history lesson involving a not so distant affair that culminated with another big con job: North Korea. The West held talks with that country as well. Promises were made. Then, one morning, the world woke up to a deafening roar of thunder: the regime had conducted a nuclear test. The North Koreans proved that a radical regime can fool the world. Do not create a new North Korean model, Netanyahu will say.

An Israeli official, speaking on condition of anonymity, told the New York Times last week, “Iran must not be allowed to repeat North Korea’s ploy to get nuclear weapons””

“Just like North Korea before it,” he said, “Iran professes to seemingly peaceful intentions; it talks the talk of nonproliferation while seeking to ease sanctions and buy more time for its nuclear program.”

The official said Netanyahu’s speech would highlight the active period of diplomacy in 2005 when the North Korean government seemingly agreed to abandon its program in return for economic, security and energy benefits.

A year later, North Korea tested its first nuclear device. Israeli officials warn something similar could happen if the United States were to conclude too hasty a deal with Mr. Rouhani. As Iran is doing today, the North Koreans insisted on a right to a peaceful nuclear energy program.

To make his case, Netanyahu’s talking points may well refer to some of the parallels he has drawn in the past between North Korea and Iran. Whether he focuses on the North Korea parallel or not, Netanyahu’s arguments will boil down to: 1) Diplomacy isn’t bad, but it won’t work; 2) we need more sanctions; 3) only a credible threat of force will stop Iran from pursuing nuclear weapons; and 4) the talks will be used by the Iranians to delay and deceive. Let’s dig a little deeper into these points.

Diplomacy won’t work:

Immediately after North Korea’s underground nuclear test on May 25, 2009, and less than a month before Iran’s contentious 2009 presidential election, Netanyahu declared that North Korea was a textbook case of what Obama could expect if he insisted on wasting time engaging in dialogue with Iran. Taking no chances about the outcome of the election, in which Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s rivals included two reformist candidates, Netanyahu said the latest Israeli intelligence estimate showed that Iran was engaged in a “national nuclear project” that was more than a one-man show. In other words, even if Ahmadinejad were to lose, Iran’s nuclear weapons program would continue. Netanyahu expressed no hope that Obama (at that point in office for just over 3 months) would ever succeed in talking Iran out of its pursuit of nuclear weapons. However, he generously agreed to give the U.S. President until the end of the year to try.

Sanctions don’t work — but we need more:

Netanyahu has flip-flopped about the efficacy of sanctions in stopping Iran’s alleged quest for a nuclear weapon. In January 2012 he told The Australian that there were signs that sanctions were finally working: “For the first time, I see Iran wobble under the sanctions that have been adopted and especially under the threat of strong sanctions on their central bank.” A week later, he complained to the Knesset’s Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee that “The sanctions employed thus far are ineffective, they have no impact on the nuclear program. We need tough sanctions against the central bank and oil industry. These things are not happening yet and that is why it has no effect on the nuclear program.”

According to an issue brief on “The Global Nonproliferation Regime” published by the Council on Foreign Relations this past June:

Although three states (India, Israel, and Pakistan) are known or believed to have acquired nuclear weapons during the Cold War, for five decades following the development of nuclear technology, only nine states have developed—and since 1945 none has used—nuclear weapons. However, arguably not a single known or suspected case of proliferation since the early 1990s—Pakistan, Iraq, Iran, North Korea, Libya, or Syria— was deterred or reversed by the multilateral institutions [i.e. sanctions] created for this purpose.

The question then becomes, if sanctions haven’t historically deterred states from seeking nuclear weapons, why invest so much time and energy imposing and demanding more of them on Iran?

The credible military threat:

In February 2013, a week after North Korea carried out its third nuclear test (UN resolutions notwithstanding), Netanyahu warned the Jewish Agency’s International Board of Governors that sanctions, no matter how crippling, could not stop Iran from developing a nuclear bomb. “Have sanctions, tough sanctions, stopped North Korea? No. And the fact that they produced a nuclear explosion reverberates everywhere in the Middle East, and especially in Iran.” Without a “robust, credible military threat,” backing up economic sanctions, Iran could not be deterred from seeking nuclear weapons, he argued.

Yet Netanyahu’s repeated calls for sanctions against Iran to “be coupled with a robust, credible military threat” fail to point out a single example where the threat — or actual use — of military force with or without sanctions has successfully deterred any state, including North Korea, from developing nuclear weapons. That’s because there are none.

“Operation Opera,” in which Israeli planes destroyed an Iraqi nuclear reactor in Osirak, is often cited by hawks as a precedent for a similar attack on Iranian nuclear facilities. Numerous security studies experts and counter-proliferation specialists agree that the operation was not nearly as successful as the Israelis claimed in preventing Saddam Hussein’s access to weapons of mass destruction. In fact, it may have accelerated, rather than stymied, Hussein’s quest for nuclear weaponry. (As a related side note, it’s doubtful Netanyahu will claim credit in his UN speech for Israel’s alleged counter-proliferation efforts in Syria, or invoke them as a model for dealing with Iran, but one never knows.)

Talks a tactic to “delay and deceive”:

Speaking during a visit to Prague in May 2012, Netanyahu stated that he had seen “no evidence whatsoever” that Iran was serious about halting its nuclear weapons program:

“It looks as though they (Iran) see these talks as another opportunity to deceive and delay, just like North Korean did for years,” Netanyahu said. “They may try to go from meeting to meeting with empty promises. They may agree to something in principle but not implement it. They may even agree to implement something that does not materially derail their nuclear weapons program,” he said.

But no credible US or Western intelligence estimate has provided evidence that Iran has a nuclear weapons program, or that it is pursuing a nuclear weapon. According to the US intelligence community’s annual worldwide threat assessment, the US believes Iran has the technical capability to make nuclear weapons, but does not know if Iran will decide to do so. However, the assessment also states that the US would know in time if Iran attempted to break out to produce enough highly enriched uranium for a bomb (implying that Iran has not made the decision yet). It goes on to note that Tehran “has developed technical expertise in a number of areas—including uranium enrichment, nuclear reactors, and ballistic missiles—from which it could draw if it decided to build missile-deliverable nuclear weapons,” making “the central issue its political will to do so.”

Deputy National Security Adviser Ben Rhodes was widely quoted last week by numerous media sources including the New York Times in such a way as to imply the U.S. also saw significant similarities between the Iranian and North Korean cases. Only the South Korean News Agency Yonhap quoted enough of Rhodes’ statement to convey his entire message. In fact, Rhodes actually said that the two cases require different strategies: “the international community needs to take different approaches toward North Korea and Iran with regard to their nuclear programs.”

Ultimately though, the bottom line remains: however fervently and persuasively Netanyahu argues that Iranian nuclear weapons capability has been achieved or is imminent, he has yet to offer any solution that will effectively address the problem. Reframing the Iranian nuclear issue in such a way that allows a pragmatist like Rouhani to make substantial and effective nuclear, economic and political reforms in Iran offers the best — and perhaps the only — chance at achieving greater Middle East stability and security. That, unfortunately, will not be among Netanyahu’s recommendations on Tuesday.

]]>by Larry Wilkerson

Now that we have heard Secretary of State John Kerry’s emotional plea for us to believe the still rather ambiguous intelligence on chemical weapons use in Syria, there are far more substantive answers to be sought from the Obama administration.

Putting aside the remaining ambiguities as [...]]]>

by Larry Wilkerson

Now that we have heard Secretary of State John Kerry’s emotional plea for us to believe the still rather ambiguous intelligence on chemical weapons use in Syria, there are far more substantive answers to be sought from the Obama administration.

Putting aside the remaining ambiguities as well as all the experience those of us over 60 years old have with any administration’s unequivocal assurances preceding its use of military force, the basic context surrounding that use against Syria still requires intense analysis.

Forget about those prematurely-born babies stripped from their cradles in the maternity wards in Kuwait, later demonstrated as a figment of war advocates’ vivid imaginations; forget about the utter certainty with which every principal in the G. W. Bush administration assured Americans of Saddam Hussein’s WMD; and forget about for a moment John Kerry’s overly emotional remarks about Syria. Just examine some pertinent facts.

First, tens of thousands of North Koreans have died from hunger imposed by at least two of the latest DPRK dictators. Is dying of hunger somehow better than dying of chemicals? Or might it be that the DPRK has no oil and no Israel? Of course, there are other examples of dastardly dictators and dying thousands; so where does one draw the line of death in the future?

Second, how does one surgically strike Syria, as the Obama administration asserts it wishes to do? That is, to use military force without becoming a participant in the ongoing conflict, simply to send a signal that chemical weapons use will not be tolerated?

Kosovo is a lousy example– where the promised three-days-of-bombing-and-the-dictator-will-cave, turned into 78 long days and a credible threat of ground forces before he actually did cave. Not to mention all the death and destruction wrought by Serbia while much the same was being hurled at it.

Libya is a lousy example because Libya is now a haven for al-Qaeda and next-door-neighbor Mali is destabilized because of it. Libya itself is hardly stable — except in the eyes of those who no longer want to look at it. Of course, the light sweet crude seems to be getting out and to the right people…

Egypt is dissolving; Iraq is returning to civil war; Lebanon is becoming destabilized by the refugees pouring into it from Syria; Jordan is looking dicey having absorbed countless Iraqis from that country’s war-caused diaspora and now taking on Syrians.

How are cruise missiles and bombs and whatever else we choose to send to Syria short of ground forces going to ameliorate this mess?

Moreover, what do we do when President Bashar al-Assad ignores our missiles and bombs and continues right on with his war? Even, perhaps, uses chemical weapons to do so? Hit him again? Remember, we are not going to become participants in the civil war, we are not going to own Syria.

The man or woman who believes that he or she can be surgical with military force is an utter fool. No plan survives first contact with the enemy. No use of military force is surgical. It is blunt, unforgiving, tending to produce results and effects never dreamt of by the user. In for a penny, in for a trillion.

Go ahead, President Obama. Strike that Syrian tarbaby. If your hands, feet and head are not eventually stuck in its brutal embrace — if you stop, reconsider, back out and are allowed to get away with it — what have you accomplished? Preserving your credibility?

US credibility in this part of the world is shot to hell already — largely by the catastrophic invasion of Iraq (not Obama’s fault, to be sure; but just as surely, America’s fault — foreigners do not differentiate presidents.) Credibility has been further shredded by continued drone strikes, by a failure to take any actions against the flow of arms from Saudi Arabia into Syria; by tacit support of the Saudi reinforcement of the dictatorship in Bahrain; and most powerfully by the failure to remain balanced — and therefore of some use — in the issue of Israel and Palestine.

When I survey that long, sunken black granite wall near the Lincoln Memorial and consider the over 58,000 names etched on it, and the two and a half million Vietnamese who, if they had such a wall, would be similarly inscribed, I get angry.

I know that President Johnson’s team, notably his national security advisor, McGeorge Bundy, assured the President that US prestige was at stake in Vietnam. LBJ’s team knew they could not win the war, but they thought they could preserve US prestige.

I just wish they had had to tell that to the families of every name on that wall — and every Vietnamese who would be on that country’s wall if it had one: you all died for prestige.

– Lawrence Wilkerson served 31 years in the US Army infantry. His last position in government was as secretary of state Colin Powell’s chief of staff. He currently teaches government and public policy at the College of William and Mary.

]]>by Peter Jenkins

The statement issued by G8 Foreign Ministers at the end of their meeting in London last week contains four paragraphs on Iran. They appear in a section devoted to Non-Proliferation and Disarmament, ahead of four paragraphs on North Korea (DPRK).

The Iran section opens [...]]]>

by Peter Jenkins

The statement issued by G8 Foreign Ministers at the end of their meeting in London last week contains four paragraphs on Iran. They appear in a section devoted to Non-Proliferation and Disarmament, ahead of four paragraphs on North Korea (DPRK).

The Iran section opens portentously with a ministerial expression of “deep concern”. The word “concern” appears twice more in the section, each time ascribed to “the international community”.

I want to explore whether the drafters of this statement were justified in giving such emphasis to “concern”, and in assuming that all but a handful of the 192 members of the UN (the international community) still feel concern regarding Iran’s nuclear activities.

I say “still” because ten years ago, when the Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) first reported that Iran had failed to report possession of small quantities of nuclear material and their use in unsafeguarded nuclear research, the membership of the IAEA (over 140 states) was pretty much united in concern.

But much has happened since then. Iran has corrected the IAEA failures uncovered in 2003. The IAEA has reported that all the nuclear material that Iran is known to possess is in non-military use. Unlike the DPRK, accused by the US of having a secret uranium enrichment program two months after this accusation was first leveled at Iran (August 2002), Iran has not withdrawn from the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), expelled IAEA inspectors, or tested nuclear devices.

Furthermore, the world’s leading intelligence agencies have come to the view that in 2003, whether from political embarrassment that year or simple prudence, Iran abandoned systematic research into nuclear weapons production, and may no longer intend to acquire nuclear weapons — a view endorsed at a political level:

- - “We do not have grounds to suspect that Iran has aspirations to possess nuclear weapons” (Russian President, Vladimir Putin, 2 December 2010);- “Are they trying to develop a nuclear weapon? No!” (US Secretary of Defence, Leon Panetta, 8 January 2012);

- “[Israel and the US] both know that Khamenei has not given the order to build a nuclear bomb” (Israeli Defence Minister, Ehud Barak, 6 August 2012).

Given all this, is it likely that “the international community” as a whole still feels concern over Iran’s nuclear activities? It would be surprising if 69 representatives of the 100-plus non-aligned segment of the international community do so. Their presidents or ministers adopted a declaration last August which contains no such expression. Instead, it contains several implicit attacks on some G8 members’ Iran policy. Inter alia, they say:

- - “opposed…the actions by a certain group of States to unilaterally reinterpret, redefine, redraft or apply selectively the provisions of [legally-binding] instruments to conform with their own views and interests and affect the rights of [State Parties]” (24.6);- “confirmed that each country’s choices and decisions in the field of peaceful uses of nuclear energy should be respected without jeopardizing its…fuel-cycle policies” (188);

- “reaffirmed… that any attack or threat of attack against peaceful nuclear facilities … poses a great danger to human beings and the environment, and constitutes a grave violation of international law” (192).

So it seems the G8 cannot reasonably claim universal support for their concerns regarding Iran. Are they themselves right, though, to be so deeply concerned “regarding Iran’s continuing nuclear and ballistic missile activities in violation of numerous UN Security Council resolutions”?

Of course in principle the violation of UNSC resolutions must always be cause for concern. But in this instance there are grounds for asking whether continuing to take so serious a view of Iran’s defiance is justified.

The first three Iran resolutions were adopted when it was still rational to fear that Iran was resolved on acquiring nuclear weapons. The resolutions demanded of Iran the suspension of all fuel cycle activities for a purpose: to hinder such acquisition. Is that demand still reasonable now that even an Israeli minister admits that Iran is not “building bombs”?

Those resolutions also demanded that Iran shed more light on its nuclear past, allow the IAEA to verify that Iran has no undeclared nuclear material and improve the timeliness with which the IAEA may detect any future diversion of nuclear material. These demands remain reasonable. But, as the G8 know, Iran is not unready to accede to them. It was doing so from 2003 until 2006; it stopped doing so only when the UNSC was brought into play to make suspension a mandatory requirement.

This suggests that the G8 have it in their power to win respect for these demands. They can do so by recognizing that the situation no longer calls for mandatory suspension and sanctions and trading repeal of these measures for the confidence-building measures they want from Iran.

Until that recognition dawns, caveat lector! Any G8 statement that treats the Iranian nuclear problem as comparable in gravity to North Korea’s numerous nuclear shenanigans is to be read with a pinch of salt.

Photo Credit: Foreign and Commonwealth Office

]]>via USIP

What steps would be necessary for Iran to build a nuclear weapon?

President Obama has estimated that it would take Iran “over a year or so” for Iran to develop a nuclear weapon. But that device would likely be crude and too large to fit on [...]]]>

via USIP

What steps would be necessary for Iran to build a nuclear weapon?

President Obama has estimated that it would take Iran “over a year or so” for Iran to develop a nuclear weapon. But that device would likely be crude and too large to fit on a ballistic missile. Producing a nuclear weapon that could be launched at Israel, Europe, or the United States would take substantially longer. Iran would need to complete three key steps.

Step 1: Produce Fissile Material

Fissile material is the most important component of a nuclear weapon. There are two types of fissile material: weapons-grade uranium and plutonium. Tehran has worked primarily on uranium. There are three levels or enrichment to understand the controversy surrounding Iran’s program:

·90 percent enrichment: The most likely route for Iran to produce fissile material would be to enrich its growing stockpile of low-enriched uranium to 90 percent purity —or weapons-grade level. Western intelligence agencies suggest Iran has not decided to enrich uranium to 90 percent.

·3.5 percent enrichment: As of early 2013, Iran had approximately 18,000 pounds of “low-enriched uranium” enriched to the 3.5 percent level (the level used to fuel civilian nuclear power plants). This stockpile would be sufficient to produce up to seven nuclear bombs, but only if it were further enriched to weapons-grade level (above the 90 percent purity level). Experts estimate Iran would need at least four months to produce enough weapons-grade uranium for one bomb using 3.5 percent enriched uranium as the starting point.

·20 percent enrichment: In early 2013, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the U.N. watchdog group that inspects Iranian nuclear facilities, said Iran also had a stockpile of 375 pounds of 20 percent low-enriched uranium, ostensibly to provide fuel for a medical research reactor. This stockpile is about two-thirds of the 551 pounds needed to produce one bomb’s worth of weapons-grade material if further enriched. If Iran accumulated sufficient quantities of 20 percent low-enriched uranium, it might be able to enrich enough weapons-grade uranium for a single bomb in a month or two.

The main issue is the status of the uranium enriched to 20 percent and the two production sites—at the Fordo plant outside the northern city of Qom and the Natanz facility in central Iran. U.N. inspectors visit these sites every week or two, however, so any move to produce weapons-grade uranium in an accelerated timeframe as short as a month would be detected. Knowing this, Iran is unlikely to act.

The speed of enrichment also depends on the centrifuges used, both their number and their quality. For a long time, Iran had used thousands of fairly slow IR-1 centrifuges to spin and then separate uranium isotopes. But since January 2013, it has started to install IR-2M centrifuges, which spin three to five times faster. In early 2013, Tehran claimed to be using about 200 IR-2Ms at the Natanz site.

Tehran might be able to enrich enough uranium for one bomb ― from 20 percent purity to 90 percent ― in as little as two weeks if it installs large numbers of advanced IR-2M centrifuges. Iran has announced its intention to eventually install as many as 3,000.

Step 2: Develop a Warhead

Iran would next have to build a nuclear device. It would need to build a warhead based on an “implosion” design if Iran wanted to deliver a nuclear device on a missile. It would include a core composed of weapons-grade uranium (or plutonium) and a neutron initiator surrounded by conventional high explosives designed to compress the core and set off a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction.

IAEA documents claim, “Iran has sufficient information to be able to design and produce a workable implosion nuclear device based upon HEU [highly enriched uranium] as the fission fuel.” The IAEA has also expressed concerns that Iran may have conducted conventional high-explosive tests at its military facility at Parchin that could be used to develop a nuclear warhead.

There is no evidence, however, that Iran is currently working to design or construct such a warhead. Even if Iran made the decision, production of a warhead small enough, light enough, and reliable enough to mount on a ballistic missile is complicated. Iran would probably need at least a few years to accomplish this technological achievement.

Step 3: Marry the Warhead to an Effective Delivery System

If Iran built a nuclear warhead, it would need a way to deliver it. Tehran’s medium-range Shahab-3 has a range of up to 1,200 miles, long enough to strike anywhere in the Middle East, including Israel, and possibly southeastern Europe. These missiles are highly inaccurate, but they are theoretically capable of carrying a nuclear warhead if Iran is able to design one.

Iran’s Sajjil-2, another domestically produced medium-range ballistic missile, reportedly has a range of 1,375 miles when carrying a 1,650-pound warhead. Tehran is the only country to develop a missile with that range before a nuclear weapon. But the missile has only been tested once since 2009, which may mean it needs further fine-tuning before deployment. Iran also relies on foreign sources for a number of components for the Sajjil-2.

Iran is probably years away from developing a missile that could hit the United States. A 2012 Department of Defense report said Iran “may be technically capable” of flight testing an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) by 2015 if it receives foreign assistance. But in December 2012, a congressional report said Iran is unlikely to develop an ICBM in this timeframe, and many analysts estimate that Tehran would need until 2020.

Is the North Korean experience relevant?

The Clinton administration confronted a similar dilemma in 1993 on North Korea’s nuclear program. The intelligence community assessed that Pyongyang had one or two bombs’ worth of weapons-grade plutonium. But the intelligence community could not tell the president with a high degree of certainty if North Korea had actually built operational nuclear weapons.

The mere existence of a few bombs’ worth of weapons-grade plutonium seemed to have a powerful deterrent effect on the United States. Washington could not be sure where the material was stored, or if the North Koreans were close to producing a weapon.

The same concerns could apply to Iran if it developed the capability to produce weapons-grade uranium so quickly that it avoids detection even at declared facilities― or if it was able to enrich bomb-grade material at a secret facility. Then Iran might be able to hide the fissile material, making it more difficult for a military strike to destroy. All the other parts of the program, such as weapons design, preparing the uranium core, and fabrication and assembly of other key weapon components, could potentially be done in places dispersed across the country that are easier to conceal and more difficult to target.

Iran may be years away from being able to place a nuclear warhead on a reliable long-range missile. But many analysts are concerned that the game is up once Iran produces enough fissile material for a bomb.

Colin H. Kahl served as the deputy assistant secretary of defense for the Middle East from 2009 to 2011. He is currently an associate professor at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service and a senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security.

]]>by Jim Lobe

I stopped reading neo-con and Dick Cheney favorite Victor Davis Hanson, “the Sage of Fresno”, after the Bush administration, largely because almost everything he wrote sounded exactly the same (cranky), and he offered no insight into what influential people were thinking. Instead, he simply repeated — in [...]]]>

by Jim Lobe

I stopped reading neo-con and Dick Cheney favorite Victor Davis Hanson, “the Sage of Fresno”, after the Bush administration, largely because almost everything he wrote sounded exactly the same (cranky), and he offered no insight into what influential people were thinking. Instead, he simply repeated — in his own kind of world-weary, father-knows-best way — whatever the neo-con echo chamber was expounding on.

This week, however, I made an exception because his latest piece in The National Review, “Iran’s North Korean Future”, addressed an emerging neo-con meme designed to take full advantage of the ongoing crisis over North Korea. To wit, if you think a nuclear Pyongyang is bad, wait until Tehran goes nuclear. (Cliff May of the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, which is trying to become for Iran what the American Enterprise Institute was for Iraq, wrote on the same topic in the Review on the same day.)

Hanson’s Review piece was subsequently published in the Washington Times and the Chicago Tribune and, to my despair, reprinted in the Early Bird edition of the Pentagon’s Current News. The central argument of the article is that a nuclear Iran would be far more dangerous than “other nuclear rogue states” such as Pakistan and North Korea. Why? Pakistan is deterred by a far larger and more powerful India, according to Hansen, while “North Korea can be “muzzled once its barking becomes too obnoxious” to China on whose patronage and support Pyongyang so clear depends. (Hansen also somewhat dubiously claims that Beijing “enjoys the angst that its subordinate causes its rivals.”)

Unlike Pakistan and North Korea, however, Iran has “no commensurate regional deterrent” that would constrain its behavior, according to Hanson. “If North Korea has been a danger, then a bigger, richer and undeterred nuclear Iran would be a nightmare,” he concludes.

Except that earlier in the same op-ed, Hansen notes that Iran would be most unlikely to attack Israel precisely because Israel’s nuclear arsenal is indeed a deterrent. Here’s the relevant passage:

Iran could copy Mr. Kim’s model endlessly — one week threatening to wipe Israel off the face of the map, the next backing down and complaining that problems in translation distorted the actual, less-bellicose communique. The point would not necessarily be to actually nuke Israel (which would translate into the end of Persian culture for a century), but to create such an atmosphere of worry and gloom over the Jewish state as to weaken the economy, encourage emigration and erode its geostrategic reputation.” [Emphasis added.]

So, even while insisting that Iran would not be deterable (because it doesn’t have a powerful next-door enemy like nuclear Pakistan has in India or a powerful patron like nuclear North Korea has in China) Hanson says in virtually the same breath that it is deterable. And this kind of analysis is rewarded by publication in the Current News!

Meanwhile, Paul Wolfowitz somewhat belatedly added his Iraq War retrospective, entitled (predictably) “Iraq: It’s Too Soon to Tell,” to the flurry of op-eds that came out at the end of March to mark the tenth anniversary of the invasion he fought so hard to realize.

Thankfully, it was not published in a U.S. medium beyond the AEI website but rather in the London-based Saudi daily, Asharq Al-Awsat. It appears primarily to be an (extremely lame) exercise in self-exculpation but is nonetheless well worth reading if for no other reason than he is probably the most high-ranking and influential policy-maker to offer an assessment on this occasion.

Unfortunately, I don’t have the time to go into specific details, but you will see some rather obvious problems in the recitation of the facts and logic.

One example: Saddam “also posed a more immediate danger [than his presumed plans to rebuild his WMD capabilities after sanctions were lifted] because terrorists, including Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi, had already begun operating from Iraqi territory to plan terrorist attacks in Europe and the Middle East [at the time of the invasion].” If that is the definition of the kind of imminent threat that justifies a U.S. invasion, what other country in the region, leave aside Pakistan, would not qualify?

(Wolfowitz also seems to put a lot of the blame on former Secretary of State James Baker for allegedly failing to heed Saudi appeals for the U.S. to intervene on behalf of the Shi’a uprising against Saddam in southern Iraq after the first Gulf war.)

The closest he gets to expressing regret is the following passage.

There are many things that one could wish had been done differently in Iraq. Even supporters of the war can make a long list. My own list stars with the US decision to establish an occupation government instead of handing to sovereignty to Iraqis at the outset, and with the four-year delay in implementing a counter-insurgency strategy. It was already clear, soon after we got to Baghdad, that the enemy was pursuing an urban guerilla strategy — in order to prevent a new Iraqi government from succeeding and so that the US would give up and leave — and an appropriate counter-insurgency strategy should have been developed much sooner.

Notice the absence of self in this passage. It wasn’t Wolfowitz who was involved in these decisions; the implication is that he opposed them. It wasn’t even the administration of President George W. Bush in which he was the Deputy Secretary of Defense and an architect of the invasion. It was “the US” that made these decisions.

In fact, it was Wolfowitz who championed de-Baathification within the administration, a policy that, combined with the reigning insecurity and de facto dissolution of the Iraqi army, made an occupation necessary. Indeed, Wolfowitz’s whole argument about the occupation was demolished by none other than Dan Senor, the spokesman for the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), at a Hudson Institute Forum five years ago, as I noted in a blog post at the time.

As for Wolfowitz’s complaint about failure to implement a counter-insurgency strategy, he, of course, has no one to blame but himself. It was he who publicly ridiculed Gen. Eric Shinseki’s warnings about the size of the force that would be needed after the invasion, and it was he who failed to read the intelligence studies that predicted the emergence of an insurgency. That he tries now to somehow separate himself from these failures by referring to the “US” rather than to the specific decision-makers (including himself) responsible for these disasters reflects, in my opinion, a certain lack of moral integrity.

Now, to be fair, a pretty big chunk of the op-ed consists of an appeal for the Sunni-led Gulf Cooperational Council (GCC) countries to do more to support Iraq, whose government is dominated by Shi’a parties. And the fact that he is making that appeal in a Saudi newspaper strongly suggests that the op-ed was consciously written with that purpose foremost in mind. “…(T)he way to keep Iraq out of Iran’s embrace is by supporting Iraq’s new government, not by distancing oneself from it,” he wrote. “This isolation, not a love of Persians, is what has pushed Iraq too close to Iran.”

Still, given Wolfowitz’s heavy responsibility for what took place a decade ago and the series of disasters that befell Iraq while he was still in a key policy-making position — he didn’t leave until 2005 — his efforts at justifying the invasion without acknowledging his personal failures and offering advice appear unseemly at best.

Photo: Former President George W. Bush (right), former Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld (center) and former Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz (left). DoD photo March 25, 2003 by R.D. Ward.

]]>by Peter Jenkins

Divining the Obama administration’s foreign policy intentions can be intellectually challenging.

At the beginning of February the US Vice President appeared to be offering Iran an opportunity to enter into bilateral talks on the nuclear dispute.

Three weeks ago the US was encouraging its European allies to review [...]]]>

by Peter Jenkins

Divining the Obama administration’s foreign policy intentions can be intellectually challenging.

At the beginning of February the US Vice President appeared to be offering Iran an opportunity to enter into bilateral talks on the nuclear dispute.

Three weeks ago the US was encouraging its European allies to review their opening position for the upcoming Almaty talks and be open to demanding a bit less of Iran while offering a little more.

Two weeks ago the Secretary of State was hailing the outcome of the Almaty meeting as useful and expressing hope that serious engagement could lead to a comprehensive agreement.

Yet last week in New York, addressing a UN Security Council committee, Ambassador Susan Rice, a member of President Obama’s cabinet, was speaking of Iran as though nothing had changed since the end of January.

There are many clever people working for the Obama administration. So I suppose we must assume that this apparent incoherence is in fact part of a highly sophisticated stratagem, which will deliver what most — though not all — of us want: peace in our time.

Any, though, who are less inclined to think more of US officials than former British diplomats do, should be forgiven for feeling perplexed — perhaps even a little worried — by Ambassador Rice’s remarks.

Let me try to illustrate that by reviewing a few of her points from the position of a Non-Aligned (NAM) member of the UN. Of course, a former British diplomat cannot hope to imagine the thoughts of NAM counterparts with pin-point accuracy. But I have rubbed shoulders with NAM diplomats for a sufficient number of years, and listened to enough of their intergovernmental interventions, to have a rough idea of what impression Ambassador Rice will have made.

“The Iranian nuclear issue remains one of the gravest threats to international security” she intoned. Really? I, as a NAM diplomat, am not sure Iran has ever violated the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), and am certain Iran has not violated that treaty’s most important provisions. Surely North Korea, which has just conducted its third nuclear test, is a greater threat? And what about Israel, which possesses hundreds of dangerous weapons of mass destruction, as well as sophisticated long-range delivery systems? What about India and Pakistan, which came close to nuclear blows in 2002? What about Israel’s refusal to withdraw from territories it has occupied for over 45 years, a standing affront to Arab self-respect? What about the potential consequences of Western-sponsored civil war in Syria, civil unrest in Iraq, and NATO withdrawal from Afghanistan?

“We meet at a time of growing risks.” Is that so? Surely the latest International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) report suggests that Iran is being careful to deny Israel’s Prime Minister a pretext to draw the US into a war of aggression?

“[Iran is] obstruct[ing] the IAEA’s investigation into the program’s possible military dimension by refusing to grant access to the Parchin site.” Well, yes. But surely the question of access to Parchin is legally more open to dispute than this implies? And hasn’t the US intelligence community concluded that Iran abandoned its nuclear weapons program ten years ago? Don’t the IAEA’s suspicions relate to experiments that may have taken place more than ten years ago and that would have involved only a few grams of nuclear material? Why all the fuss?

“More alarming still…Iran is now….installing hundreds of second-generation centrifuges”. Why is this so alarming? Surely Iran has declared this installation to the IAEA, will submit the machines’ operations to frequent IAEA inspection and intends to use them to produce low-enriched uranium for which Iran will account? Developing centrifuge technology under IAEA safeguards is not a treaty violation.

“These actions are unnecessary and thus provocative.” Since when have states been entitled to dictate what is necessary to one another? Some states certainly don’t see these actions as provocative.

“[Iran’s missile launches] allow Iran to develop a technology that [could] constitute an intolerable threat to peace and security.” Iran has no treaty obligation to refrain from developing missile technology. Many other states have done so. And, didn’t I (NAM diplomat) read recently on the US Congressional Research Service that Iran is unlikely to have an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) by 2015?

“Working together, we can continue to clarify for Iran the consequences of its actions and show Iran the benefits of choosing cooperation over provocation.” My, that sounds patronising, even a little threatening! Will it encourage Iranians to believe that the latest US offer of engagement is sincere?

So what, US readers may feel. The US can say what it likes; it’s a Great Power. Yes, but a power that has the misfortune to be great in an age when greatness confers responsibility for nurturing a law-based international system.

It doesn’t do much good to that system for US ambassadors to sound unreasonable, alarmist, bereft of a sense of proportion and perhaps a little inclined to double standards. Good leaders lead from the middle, not one of the extremities.

And could it be the case that the US is a Great Power that needs a diplomatic solution to an intractable dispute? Neither the Pentagon nor the US public wants another war at this stage. Sanctions have been hurting innocent Iranians but benefitting Iran’s Revolutionary Guards and conservative elite, who feel confident of their ability to contain popular discontent.

When one is running out of options, negotiating theorists suggest that building trust in one’s good faith is a better tactic than dishing out hyperbole and half-truths.

Photo Credit: US Embassy New Delhi/Flickr

]]>by Peter Jenkins

Speaking on 12 February about the latest North Korean nuclear test, the outgoing US Defense Secretary said (according to the BBC): “We’re going to have to continue with rogue states like Iran and North Korea.” Does Iran deserve to be bracketed with North Korea? Is Iran a rogue [...]]]>

by Peter Jenkins

Speaking on 12 February about the latest North Korean nuclear test, the outgoing US Defense Secretary said (according to the BBC): “We’re going to have to continue with rogue states like Iran and North Korea.” Does Iran deserve to be bracketed with North Korea? Is Iran a rogue state?

Unlike North Korea, Iran has remained a party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). It has continued to submit to international inspection the nuclear material in its possession. It has never expelled the inspectors of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). It has never tested a nuclear explosive device. It is assessed to be acquiring a capability to make nuclear weapons, but to be undecided and open to persuasion to refrain from their manufacture.

In a 1994 issue of Foreign Affairs, the US National Security Adviser of the time argued that, to be classified as a rogue, a state had to commit four transgressions: pursue weapons of mass destruction (WMD), support terrorism, severely abuse its own citizens, and stridently criticize the United States.

It is questionable whether Iran is pursuing WMD. Ten years ago, Western officials believed that Iran sought nuclear weapons. Since late 2007, there is growing support for the thesis that Iran is developing, as other Non-Nuclear Weapon States have done, the ability to try for nuclear weapons if it sees advantage in doing so — a different matter, legally and practically.

Evidence for the pursuit of chemical (CW), biological, and toxin weapons, is scant to non-existent. Having been gassed by Western-supplied Iraqi troops in the 1980s, the Iranians developed CW technologies and built production facilities, but they abandoned the program when they decided to adhere to the CW Convention in 1998.

Support for terrorism is another matter. There is ample evidence of Iranian support for groups that the US government regards as “terrorist”. But an old saying — “one man’s terrorist is another’s resistance hero” — is not irrelevant, since the main beneficiaries of Iranian support have been Hezbollah and Hamas (neither of which is considered “terrorist” by the vast majority of UN member states).

Iran’s Islamic government treats political dissidents badly and has the blood of thousands of political opponents on its hands, albeit mainly from the first decade of its existence. Iranians enjoy far greater freedom, and are more empowered, than North Koreans, but being politically active outside the system can cost them dearly.

A Strident critic of the US? Guilty as charged. But ought that to be a criterion of roguishness in the US, a democracy that cherishes freedom of speech?

As it happens, in June 2000 Iran was cleared of the rogue state charge by no less an authority than the then US Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright.

Of course, verbally abusing Iran as a “rogue state” would be of no import if the West had no need of some sort of understanding with Iran about the future scope of its nuclear program.

That is not the case, however. Instead, it has become ever clearer that a nuclear understanding with Iran is in the West’s interest. Western diplomats used to imagine that they could dispense with dialogue and negotiation. Sanctions or the use of force would put a stop to Iran’s development of dual-use technologies and its exploitation of loop-holes in the NPT. Few still harbor that illusion.

Imposing sanctions has failed to bend Iran to the West’s will; at best, it has created a pile of chips that can be exchanged for Iranian concessions in a nuclear negotiation.

And using force no longer looks appealing. The cost/benefit calculation has evolved. The potential reckoning is not quite as grim as in the North Korean case, where the use of force could provoke the obliteration of much of Seoul. But the risk that Iran would retaliate, if attacked, by destroying Saudi desalination plants and oil terminals is a major deterrent, and that is not the only concern.

Verbal abuse could also be ignored if Iran’s leaders had shown themselves indifferent to it. The evidence, however, points in the opposite direction. As recently as 7 February, Iran’s Supreme Leader warned the US against imagining that any form of aggression would conduce to a nuclear settlement.

I have been dipping into a book written by Senator William Fulbright in 1966: The Arrogance of Power. Worried by the worsening situation in South East Asia, and the absence of formal relations with Communist China, the Senator regrets several tendencies: seeing China as the embodiment of an evil and frightening idea; “dehumanising” the Chinese adversary; interpreting information to fit negative preconceptions; and avoiding communication for fear of “giving something away”. He calls on his fellow-countrymen, instead, to treat China with “the magnanimity that befits a great [US] nation”. “Bellicosity is a mark of weakness and self-doubt.” “The true mark of greatness is magnanimity.”

The US is still a great nation. Can it bring itself to treat Iran with magnanimity?

]]>By David Isenberg

Apart from death and taxes, one other thing has also appeared inevitable, at least for the past two decades: Iran will acquire a nuclear weapons capability.

Yet, despite all the near frantic demands for sanctions, clandestine action, sabotage, and outright military strikes to prevent Iran’s presumed inexorable march [...]]]>

By David Isenberg

Apart from death and taxes, one other thing has also appeared inevitable, at least for the past two decades: Iran will acquire a nuclear weapons capability.

Yet, despite all the near frantic demands for sanctions, clandestine action, sabotage, and outright military strikes to prevent Iran’s presumed inexorable march towards that capability, one thing keeps getting overlooked: Iran has not managed to develop a nuclear weapon.

How is that possible? As states go, Iran has a reasonably well-developed scientific and industrial infrastructure, an educated workforce capable of working with advanced technologies, and lots of money. If Pakistan, starting from a much lower level, could develop nuclear weapons, why hasn’t Iran?

That overlooked question was the subject of an important but largely ignored past article, “Botching the Bomb: Why Nuclear Weapons Programs Often Fail on Their Own — and Why Iran’s Might, Too” in Foreign Affairs journal.

In the May/June 2012 issue, Jacques E. C. Hymans, an International Relations Associate Professor at the University of Southern California and author of the book Achieving Nuclear Ambitions: Scientists, Politicians, and Proliferation (from which his article was adapted) wrote:

The Iranians had to work for 25 years just to start accumulating uranium enriched to 20 percent, which is not even weapons grade. The slow pace of Iranian nuclear progress to date strongly suggests that Iran could still need a very long time to actually build a bomb — or could even ultimately fail to do so. Indeed, global trends in proliferation suggest that either of those outcomes might be more likely than Iranian success in the near future. Despite regular warnings that proliferation is spinning out of control, the fact is that since the 1970s, there has been a persistent slowdown in the pace of technical progress on nuclear weapons projects and an equally dramatic decline in their ultimate success rate.

To paraphrase Sherlock Homes, Iran is an example of a nuclear dog that has not barked. In Hyman’s view, Iran’s lack of progress can only partly be attributed to US and international nonproliferation efforts.

But the primary reason is:

…mostly the result of the dysfunctional management tendencies of the states that have sought the bomb in recent decades. Weak institutions in those states have permitted political leaders to unintentionally undermine the performance of their nuclear scientists, engineers, and technicians. The harder politicians have pushed to achieve their nuclear ambitions, the less productive their nuclear programs have become.

Conversely, US and Israeli efforts may actually be helping Iran to someday achieve a nuclear weapons capability.

Meanwhile, military attacks by foreign powers have tended to unite politicians and scientists in a common cause to build the bomb. Therefore, taking radical steps to rein in Iran would be not only risky but also potentially counterproductive, and much less likely to succeed than the simplest policy of all: getting out of the way and allowing the Iranian nuclear program’s worst enemies — Iran’s political leaders — to hinder the country’s nuclear progress all by themselves.

Generally examining the progress of contemporary aspiring nuclear weapons states, Hymans notes that seven countries launched dedicated nuclear weapons projects before 1970, and all of them succeeded in relatively short order. By contrast, of the ten countries that have launched dedicated nuclear weapons projects since 1970, only three have achieved a bomb. And only one of the six states that failed — Iraq — had made much progress toward its ultimate goal by the time it gave up trying. (The jury is still out on Iran’s program.) What’s more, even the successful projects of recent decades have required a long time to achieve their goals. The average timeline to the bomb for successful projects launched before 1970 was about seven years; the average timeline to the bomb for successful projects launched after 1970 has been about 17 years.

In the case of Iran, Hymans notes:

Iran’s nuclear scientists and engineers may well find a way to inoculate themselves against Israeli bombs and computer hackers. But they face a potentially far greater obstacle in the form of Iran’s long-standing authoritarian management culture. In a study of Iranian human-resource practices, the management analysts Pari Namazie and Monir Tayeb concluded that the Iranian regime has historically shown a marked preference for political loyalty over professional qualifications. “The belief,” they wrote, “is that a loyal person can learn new skills, but it is much more difficult to teach loyalty to a skilled person.” This is the classic attitude of authoritarian managers. And according to the Iranian political scientist Hossein Bashiriyeh, in recent years, Iran’s “irregular and erratic economic policies and practices, political nepotism and general mismanagement” have greatly accelerated. It is hard to imagine that the politically charged Iranian nuclear program is sheltered from these tendencies.

Hymans accordingly derived four lessons.

- The first is to be wary of narrow, technocentric analyses of a state’s nuclear weapons potential. Recent alarming estimates of Iran’s timeline to the bomb have been based on the same assumptions that have led Israel and the United States to consistently overestimate Iran’s rate of nuclear progress for the last 20 years. The majority of official US and Israeli estimates during the 1990s predicted that Iran would acquire nuclear weapons by 2000. After that date passed with no Iranian bomb in sight, the estimate was simply bumped back to 2005, then to 2010, and most recently to 2015. The point is not that the most recent estimates are necessarily wrong, but that they lack credibility. In particular, policymakers should heavily discount any intelligence assessments that do not explicitly account for the impact of management quality on Iran’s proliferation timeline.

- The second is that policymakers should reject analyses based on assumptions about a state’s capacity to build nuclear programs in secret. Ever since the mid-1990s, official proliferation assessments have freely extrapolated from minimal data, a practice that led US intelligence analysts to wrongly conclude that Iraq had reconstituted its weapons of mass destruction programs after the Gulf War. The US must guard against the possibility of an equivalent intelligence failure over Iran. This is not to deny that Tehran may be keeping some of its nuclear work secret. But it is simply unreasonable to assume, for example, that Iran has compensated for the problems it has faced with centrifuges at the Natanz uranium-enrichment facility by hiding better-working centrifuges at some unknown facility. Indeed, when Iran has tried to hide weapons-related activities in the past, it has often been precisely because the work was at the very early stages or was going badly.

- The third is that states that poorly manage their nuclear programs can bungle even the supposedly easy steps of the process. For instance, based on estimates of the size of North Korea’s plutonium stockpile and the presumed ease of weapons fabrication, US intelligence agencies thought that by the 1990s, North Korea had built one or two nuclear weapons. But in 2006, North Korea’s first nuclear test essentially fizzled, making it clear that the “hermit kingdom” did not have any working weapons at all. Even its second try, in 2009, did not work properly. Similarly, if Iran eventually does acquire a significant quantity of weapons-grade highly enriched uranium, this should not be equated with the possession of a nuclear weapon.

- The fourth lesson is to avoid acting in a way that might motivate scientific and technical workers to commit themselves more firmly to the nuclear weapons project. Nationalist fervor can partially compensate for poor organization. Accordingly, violent actions, such as aerial bombardments or assassinations of scientists, are a loser’s bet. As shown by the consequences of the Israeli attack on Osiraq, such strikes are liable to unite the state’s scientific and technical workers behind their otherwise illegitimate political leadership. Acts of sabotage, such as the Stuxnet computer worm, which damaged Iranian nuclear equipment in 2010, stand at the extreme boundary between sanctions and violent attacks, and should therefore only be undertaken after extremely thorough consideration.

- David Isenberg runs the Isenberg Institute of Strategic Satire (Motto: Let’s stop war by making fun of it.). He is author of the book Shadow Force: Private Security Contractors in Iraq and blogs at The PMSC Observer and the Huffington Post. He is a senior analyst at Wikistrat, an adjunct scholar at the CATO Institute, and a Navy veteran.

Photo: Iran’s first nuclear power plant in Bushehr, Iran, on August 21, 2010. UPI/Maryam Rahmanianon.

]]>