by Adnan Tabatabai

With the July 20 deadline for reaching a final deal on Iran’s nuclear program looming, Tehran and world powers will resume negotiations on May 13 in Vienna.

While the talks could theoretically be extended, efforts by Iran and the P5+1 (the U.S., Britain, France, China, and Russia [...]]]>

by Adnan Tabatabai

With the July 20 deadline for reaching a final deal on Iran’s nuclear program looming, Tehran and world powers will resume negotiations on May 13 in Vienna.

While the talks could theoretically be extended, efforts by Iran and the P5+1 (the U.S., Britain, France, China, and Russia plus Germany) to strike a final deal soon will be strong, given the considerable domestic pressure faced by the negotiating parties, particularly Iran and the United States.

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and his Foreign Minister Javad Zarif do not want to risk providing domestic hard-liners, the arch-conservative clerics and far-right principlist members of Parliament (MP) who have criticized the government’s negotiating strategy, with another target by asking for their patience until the end of 2014 or early 2015.

Hence, the Islamic Republic is well on track in complying with the Joint Plan of Action (JPOA), the historic interim deal reached in Geneva on November 24, 2013. But consequently, and as a dialectic effect, this progress has also stirred up anxiety among Iranian sceptics.

Hard-line opposition taking center stage in Iran

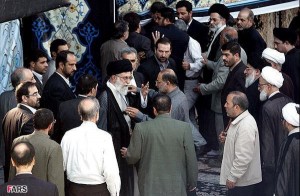

A public conference, entitled “We’re concerned” (“delvaapasim”), was held at the former U.S. Embassy in Tehran on May 3. The panellists included conservative and far-right leaning parliamentarians, former government officials and think-tankers.

The venue of the conference was obviously symbolic. The choice illustrates the ideological nature of the agenda, notwithstanding the actual substantial concerns raised by the participants.

For the most part, Iranian hardliners argue that Foreign Minister Zarif’s negotiating team is giving away too much, too soon and therefore risks selling out Iran’s national interests.

A joint statement issued by the conference’s key speakers includes specific demands for the negotiations that can be grouped into the following: preserve Iran’s rights to an independent, peaceful nuclear program according to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT); sanctions — particularly banking sanctions — must be lifted within a clear-cut timeline; and the negotiations should be transparent and opened to the public before the final agreement is signed as well as subject to approval by Iran’s Parliament and the Supreme National Security Council.

These demands indicate a sense, experienced by hard-liners, of being left in the dark about the details of the negotiations. Thus, not only are these influential stakeholders highly sceptical of the strategies adopted by the P5+1, but also of Iran’s very own negotiating team.

“What we are saying is that this [negotiating] team is entering the talks with a soft position and a diplomacy of smiling, which is not appreciated in a country like Iran that has given martyrs and struggled many years for the victory of its Islamic Revolution,” Mohammad Hossein Karimi-Ghadoosi, a parliamentarian and leading figure of the hard-line Islamic Endurance Front (Jebhe-ye paaydaari), told LobeLog.

Karimi-Ghadoosi also believes Iran might be perceived as weak with such a reconciliatory approach.

“Even though the spell of [failed] talks has been broken after eight years, we cannot see any meaningful progress if we look at all this rationally,” he said.

“Some disoriented media and those supporting the government are creating this positive atmosphere,” added Karimi-Ghadoosi, who is also a member of the important parliamentary committee for National Security and Foreign Affairs.

The concerns of critics like Karimi-Ghadoosi regarding the framework of the agreement may, in fact, be settled depending on how transparently and responsively Zarif’s team conducts the remaining negotiating sessions. With regard to Iran’s overall approach, however, these deeply conservative currents will be hard to satisfy.

Resistance as an intrinsic value

The political ideology promoted by this far-right conservative faction constantly reinvigorates the revolutionary spirit of the late 1970s. Enmity towards the West and the United States in particular is a raison d’être that will not be abandoned.

In order to flourish, this political spectrum needs tensions with the West and its allies. Isolation and segregation, rather than dialogue and integration, are what these groups prefer in Iran’s grand foreign policy strategy, which should be oriented towards furthering Iran’s status as a respected regional power.

“Negotiations on behalf of the system of the Islamic Republic must follow the path of Islamic ideals,” said Karimi-Ghadoosi in reply to my question about what negotiation strategy he prefers.

Hence this faction’s glorification of Saeed Jalili, Iran’s former lead nuclear negotiator under President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Jalili was the recalcitrant figure preferring to lecture his negotiating partners on core Islamic values rather than emphasizing the importance of reaching common ground for resolving this conflict.

In contrast, Zarif’s reconciliatory approach, in the far-right principlists’ view, does not only lead to selling out on Iranian interests, but also contradicts the fundamentals of the nezaam — the system of the Islamic Republic.

One media outlet affiliated with the Endurance Front described the May 3 conference as an illustration of how various “revolutionary currents” are able to turn core ideals and concerns into “operational directives”.

This article also explicitly mentioned that “this gathering will not have matched the taste of reformists,” underlining the event’s purposefully factional nature.

Is Rouhani’s government responsive?

A successful Rouhani presidency depends on many factors, including the way it chooses to respond to these waves of criticism.

Warning remarks by political heavy-weights such as Alaeddin Boroujerdi, chairman of the National Security and Foreign Affairs Committee of Parliament, add to on-going internal pressure for Rouhani to conform.

Anticipating more pressure by the P5+1 on Iran to dismantle its ballistic missile capacity, Boroujerdi recently declared that “Iran’s missile power is not an issue for negotiations,” in comments posted on the hard-line Fars News Agency.

One of the shortcomings of former President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) was the failure of his reformist camp to integrate and address public criticism from conservative factions — a phenomenon that was performed in reverse by the Ahmadinejad government in an even more distinct fashion.

President Rouhani, a centrist through and through, tried to reach out to critics during a recently televised live interview. It seemed, in fact, that this media appearance was used for an overall — though soft-toned — rebuttal against his adversaries.

“We have not kept and will not keep anything secret,” stressed Rouhani during the April 29 TV appearance.

The “red line”, the president held, “is the right of the nation,” which will be preserved by the “thoroughly experienced” negotiating team.

Rouhani also said that bold slogans alone would not lead to political outcomes.

“From the beginning we have said that our approach in the negotiations is that of a win-win approach,” he added.

There’s no indication as of yet that the president’s remarks will tame any of his most outspoken critics, such as Ruhollah Hosseinian, Mehdi Kouchakzadeh, Seyed Mohamad Nabavian or Hamid Rasaei, all parliamentarians who were key speakers at the May 3 conference. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s support for Rouhani is well recognized in those circles, but the hard-liners’ scepticism remains.

Rouhani and Zarif must effectively respond to these figures to avoid further radicalizing their positions. Since increasing pressure on the government would simultaneously lead to increasing pressure on the Supreme Leader, the latter’s support for the government could also become less vocal. Khamenei, too, must ultimately respond to his most loyal followers.

Photo: Participants of Tehran’s May 3 “We’re concerned” conference, which was held at the former U.S. embassy. Credit: SNN/Ali Mokhtari

]]>by Ali Reza Eshraghi

In the current debate over the November 24 interim deal with Iran on its nuclear program, an important lesson from Politics 101 is neglected: state and regime are two conceptually different terms. But when it comes to Iran, US foreign policy has systematically been incompetent in grasping this [...]]]>

by Ali Reza Eshraghi

In the current debate over the November 24 interim deal with Iran on its nuclear program, an important lesson from Politics 101 is neglected: state and regime are two conceptually different terms. But when it comes to Iran, US foreign policy has systematically been incompetent in grasping this distinction.

State refers to a sovereign political entity, which (at least in theory) is supposed to pursue the common good of its population. Regime, on the other hand, signifies an authoritarian form of governance and its ruling elites.

However, the rhetorical use of this word can be biased and highly politically motivated. In Western media one recurrently hears phrases such as “Iranian regime” and “Islamic regime” and not so much “Saudi regime,” despite Iran having significantly greater democratic features than the kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Louis XIV of France once said: “L’Etat c’est moi,” I am the state. In the discourse over Iran’s nuclear program, it is often mistakenly assumed that the regime (along with the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei) is the state. Subsequently, the nuclear conundrum is framed as only the problem of a regime that is greedily obsessed with its own survival, and not that of a state bound to consider long-term national interests.

If one sees a problem as a nail, the solution would be to look for a hammer. In this regard, it is not surprising that many members of the U.S. congress, assuming that more pressure will ultimately force capitulation by the regime, are pushing (though apparently defeated for the time being) for evermore sanctions against Iran.

And when it comes to negotiating with Iran, we see that the old Kremlinology of the Soviet era is ludicrously imitated, with moderate President Hassan Rouhani being compared to Mikhail Gorbachev. All the speculations are focused on how far the Iranian President could go in selling an accord to other players in the regime, and ultimately how much the whole regime, including Rouhani, can be trusted.

But what about the Iranian People? Some argue they would be happy for any deal as long as it alleviates the suffering caused by economic sanctions. It is even claimed that the democratic Iranian opposition is worried a nuclear agreement would empower the regime.

These assertions are inaccurate.

Two days after the historic phone conversation between Presidents Barack Hussein Obama and Hassan Rouhani, a rap song titled “Hassan & Hussein” went viral. The lyrics encouraged Iran-US reconciliation, but cautioned Rouhani: “Just remember when you are dancing [with Obama] / Not to give away the country two-handedly to [him] the foreigner.”

A recent poll by the Zogby Research Service shows 96% of Iranians (also the majority of Rouhani supporters) believe “maintaining the right to advance a nuclear program is worth the price being paid in economic sanctions and international isolation.”

Some Iranian opposition groups — though hateful of the regime — also believe that the nuclear dispute with the West should not be resolved at the price of damaging the pride and interests of the country.

For example Ardeshir Zahedi, the Shah’s last Ambassador to the US, in an interview with BBC Persian in July 2012 defended the nuclear program of a regime that has forced him into exile: “Iranians must maintain their patriotism. No matter who is in power, Iran is our country.”

Akbar Etemad, the founder of the Atomic Energy Organization during the Shah’s regime, even recommends that Iran withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in order to keep its uranium enrichment program. This is the same position that some of the regime’s hardliners have insisted on.

Moreover, the Green Movement leaders (the largest democratic movement in Iran since the 1979 revolution, which the U.S. was sympathetic toward) are also against the Iranian regime signing a nuclear deal at the cost of disregarding national interests.

In October 2009, Iran’s top negotiator Saeed Jalili welcomed a deal in which Iran would send enriched uranium abroad. But Mir-Hossein Mousavi, the Green Movement leader who has been under house arrest for more than a thousand days, accused the regime of “making a deal over the Iranian nation’s long-term interests.” The Supreme Leader later rejected the deal.

Another severe comment was made in May 2010 when Iran signed a nuclear deal with the mediation of Brazil and Turkey (initially encouraged by President Obama but later rejected). This time Zahra Rahnavard, Mousavi’s wife who has also been under house arrest, admonished the agreement as “worse than the disgraceful” Gulistan Treaty.

Coincidentally, this October the Iranian media commemorated the 200th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Gulistan between the Iranian and Russian empires following the peace negotiations that were mediated by Great Britain.

Gulistan (1813) and its following Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828) in which Iran had to give up a great deal of territories and rights have deeply haunted the Iranian psyche.

In the Persian vocabulary “Turkmenchay” has become a metaphor for any humiliating compromise that jeopardizes national interests. In fact, after the recent Geneva agreement Iranians active on social media were wondering if it is another Turkmenchay or not. Luckily, the majority of Iranians don’t believe so although Abolhassan Banisadr, a prominent opposition figure who served as the first President of post-revolutionary Iran, has called the interim deal “worst than the Turkmenchay Treaty.”

To further understand the situation, let’s compare this metaphor to another one, which is often used in explaining the behavior of the regime:

In July 1988 after the eight-year Iran-Iraq war, the Supreme Leader of the time Ayatollah Rouhollah Khomeini reluctantly accepted UN Security Council Resolution 598 and the immediate ceasefire. He equated his decision (like Socrates) to drinking the poisonous chalice. Since then, pundits have participated in an incongruous scholastic dispute over what conditions would lead the current Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to drink the proverbial poison and accept a nuclear deal like his predecessor.

Khomeini has been lambasted by many Iranians for prolonging the war with Iraq but no one has condemned his decision to accept the UN Security Council resolution as an act of giving away a piece of land or undermining national interests and rights.

The real problem for the current Iranian regime headed by Ayatollah Khamenei is not about drinking the poisonous chalice. It has to do with the signing of a nuclear Turkmenchay. Realpolitik suggests that the regime should not be trapped between the Scylla of ever-growing sanctions and the Charybdis of a humiliating unilateral concession.

The US President has apparently grasped this notion. Speaking at the Brookings Institution’s Saban Forum last Saturday, Obama rejected that Iran would surrender under more sanctions and military threats: “I think [this notion] does not reflect an honest understanding of the Iranian people or the Iranian regime.”

When debating the recent Geneva deal and the prospect of a comprehensive agreement, US foreign policy makers, especially Congress, need to distinguish between Iran as a regime and Iran as a state. “What’s the difference?” they might ask.

Yet, as the literary critic Paul De Man once brilliantly explained, “What’s the difference” in some situations could be an answer rather than a question that indicates the responder does not “give a damn what the difference is.” This would be an imprudent answer from the US Congress.

Photo Credit: ISNA/Mehdi Ghasemi

]]>by Ali Reza Eshraghi

News media accounts of reactions from Iran to the recent talks in Geneva remind me of a joke that has gone viral there:

A salesman shows a variety of hearing aids ranging in cost from one to a thousand dollars to a customer, who then asks, “How well does [...]]]>

by Ali Reza Eshraghi

News media accounts of reactions from Iran to the recent talks in Geneva remind me of a joke that has gone viral there:

A salesman shows a variety of hearing aids ranging in cost from one to a thousand dollars to a customer, who then asks, “How well does the one dollar one work?” The salesman responds, “It doesn’t work at all! But, people speak louder when they see you wearing it.”

For the first time, different political factions within the Islamic republic of Iran are in agreement about President Hassan Rouhani’s method for resolving the nuclear issue and negotiating with the United States. But local and international media coverage has focused on Iranian radical groups who have shrunk in size and been marginalized after June’s presidential election. While this group occupies a small space in Iran’s current nuclear discourse, it has been presented as a major actor by the media.

Much of this coverage focuses on Kayhan, the Iranian daily newspaper, and its editor-in-chief, Hossein Shariatmadari, who has openly criticized the Iranian delegates for keeping the details of their negotiations with the P5+1 powers (the United States, Britain, France, Russia and China plus Germany) confidential. For Shariatmadari, this secrecy is an indication that the Iranian delegation is making a bad deal.

Of course, Khayan and Shariatmadari are not the only ones who have criticized Iranian diplomats for keeping things under wraps when it comes to the nuclear issue. In October 2009, when the Saeed Jalili-headed negotiation team was trying to make a deal with the P5+1 in Geneva, Iranian reformist media also complained about the lack of available details on the discussions.

At that time, Mir-Hossein Mousavi, the sidelined candidate of Iran’s 2009 presidential election, accused the negotiators of trading the long-term interests of Iranians for “nothing” in a statement.

And last year — amid rumors of a meeting between Ali Akbar Velayati, a senior aide to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, with American officials — Kalameh, the flagship website of the opposition Green Movement, demanded that the negotiations be “transparent and [conducted] in front of people.”

Shrinking prominence

This time it’s the hardline Kayhan that has printed the loudest complaints against the confidential negotiations. But things are different now. Not long ago, each time Kayhan started a game of ball, it was immediately picked up and passed around in the Principlist front. Today, no one is willing to play along with the well-known daily.

Indeed, other conservative media outlets affiliated with the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corp (IRGC) apparently have no problem with the nuclear negotiations remaining confidential. Here is Sobh-e Sadeq, the official IRGC weekly, expressing satisfaction in its post-Geneva talks coverage:

“The Iranian delegation stressed the importance of respecting Iranian nation’s red lines, as well as the need of change in the position of the West from selfishness to a win-win interaction. [Our delegation] would not back down from the nation’s rights.”

Even more surprisingly, the IRGC has absorbed Rouhani’s vocabulary and is talking about a “win-win interaction with the US.” The Javan daily, another media outlet associated with the IRGC, stressed on Monday that the actions of the Rouhani administration “have the permission of the Supreme Leader.” Javan took this a step further by arguing that even if the administration was unsuccessful in the negotiations, Iran would still emerge victorious because it would be obvious that it was the Americans who, contrary to their claims, have no interest in resolving disputes and restoring relations.

Gholam Ali Haddad Adel, the head of the Majlis Principlist faction whose daughter is married to the Supreme Leader’s son, has also supported the confidentiality of the nuclear negotiations. Considered a hardliner, Haddad Adel, who used to favor Kayhan, could have remained silent in this debate. But he has criticized the newspaper for basing its suspicion of Iran’s diplomatic team on what he considers “the words of the Zionist media.”

With such remarks, Haddad Adel is — perhaps unintentionally — paving the road for reformists to launch a more powerful attack against the radicals. Mir-Mahmoud Mousavi, the former Director General of the Foreign Ministry and the brother of Mir-Hossein Mousavi, has also accused Iranian hardliners of using the language of Israeli hardliners. He believes they both “are trying to weaken Iran’s position in the talks.”

The position of Haddad Adel, the IRGC or even Ahmad Khatami, the radical and sometimes callous Tehran Friday Prayers Leader who also said Rouhani’s administration should be trusted, has confused analysts who measure Iranian politics with a who-is-closer-to-the-Supreme-Leader tape. These pundits are uncomfortably surprised each time they come across such perplexing results. The last such surprise occurred during Iran’s 2013 presidential election when Saeed Jalili, Iran’s nuclear negotiator who was touted as a favorite of the Supreme Leader, lost the vote.

After Ahmadinejad

Of course, it’s crucial to observe certain significant developments in Iran’s nuclear and foreign policy discourse that have occurred since Rouhani took office a few months ago. First, Iranian media can now write more openly and include a variety of opinions about their country’s controversial politics. This is why Mohammad Mohajeri, the editor-in-chief of the popular Khabar Online website and former member of the editorial board of Kayhan, reminded Shariatmadari that Jalili’s former negotiating team had tougher restrictions for the press. Before, “the press would get some burnt intelligence and were then told not to even discuss that useless information because of the confidential nature of the talks.” Compare that situation to the present when trying to gauge the level of change. Last week, for the first time, Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif took a group of Iranian reporters from various media outlets to Geneva. Each day they were briefed repeatedly by members of the Iranian team.

That the reformist media are not alone in attacking and quibbling with the hardliners is another new development. The moderate and progressive Principlists, in an unwritten division of labor with the reformists, have taken on the task of silencing the radicals themselves. Popular news websites affiliated with the Principlists like Alef, Khabar Online and Tabank have constantly — albeit with a softer tone — criticized Iran’s radicals since the talks in Geneva.

Bijan Moghaddam, the managing director of the widely circulated Jam-e Jam daily and the former political editor of the hardliner Fars News Agency, has warned the radicals that the “Iranian society has banished them” and asked hardliners to voice their criticism logically and “without creating a ruckus and swearing.”

Finally, there is now a visible rhetorical shift in the debate over Iran’s foreign policy. Critics of Rouhani’s diplomacy team do not merely rely on mnemonic tropes and the Islamic Republic’s ideological repertoire in their arguments. They are also invoking Iran’s “national interest” in criticizing the administration’s diplomatic method. Such changes are even visible in Khayan’s tone. For example, the daily recently criticized Rouhani for publically announcing ahead of the Geneva talks that the treasury is empty, saying that such statements would weaken Iran’s negotiating position.

In such an atmosphere, it’s not surprising that critics of the government’s foreign policy claim they are aiding the administration’s negotiating strategy. As a radical commentator recently said in an interview with the Javan daily, “President Rouhani can use the views of those opposing the talks with the US as powerful leverage to haggle with the US.”

Photo: Gholam Ali Haddad Adel greets Hossein Shariatmadari. Credit: Jam News

]]>by Farideh Farhi

I read about the Obama-Rouhani phone call in Farsnews, the hardline Iranian agency sometimes referred to as False News for the way it manages to distort certain events. (The official Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) was apparently the first to report the call). Feeling skeptical, I turned [...]]]>

by Farideh Farhi

I read about the Obama-Rouhani phone call in Farsnews, the hardline Iranian agency sometimes referred to as False News for the way it manages to distort certain events. (The official Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) was apparently the first to report the call). Feeling skeptical, I turned to the New York Times where no mention of the event could be found as of yet. By the time I turned to CNN International — which, unlike its American counterpart, thinks its audience deserves better than frivolity and drama — Obama was already talking about Syria with the streaming headlines below his image confirming the phone call.

Obama’s words were not that different from his conciliatory speech at the UN General Assembly, but the news of the phone call between him and Hassan Rouhani has been met with silent awe by all and smiles from most, as documented here by Ali Reza Eshraghi.

I have been in Tehran since the beginning of this month, mostly absorbing conversations everywhere about what Rouhani can do, cannot do, and should do. But I have also heard plenty of talk and questions about Obama and his presumed lack of backbone.

Conversations usually begin with a question directed at me, the American political scientist in the room, about the rhymes and reasons of US policy on Iran. Of course, the questions are usually rhetorical since everyone in the room is more of a political “expert” than I am. This is Tehran, after all…

It usually takes a few seconds before the cacophonous discussion turns to the influence of Israel and Israeli lobbies in the US. “They would not allow it” is the repeated declaration and lament.

But Obama’s UN speech and phone call is raising eyebrows — even a momentary silence. It’s now time to watch and be cautiously optimistic about Obama’s ability for a pushback.

Meanwhile, the Iranian President is also impressing people with his presumed grit. I heard someone say yesterday that Rouhani probably would not have arranged to receive the phone call had the hardline press not acted so pleased with his refusal to shake Obama’s hand and not made fun of the reformist press for hoping for such an encounter.

Rouhani has accomplished more than what most expected from him both domestically and internationally. The release of some political prisoners; a returning degree of calm to economic expectations; the resurgence of a vibrant political press; the opening of the cultural arena; and public commitment to the resolution of the nuclear issue all confirm a re-direction at the top in response to public sensibilities. But few expected this re-direction to have palpable results so soon. The mood remains patient, but clearly pleased.

Yes, a shoe was thrown at Rouhani upon his return from New York City from a group of about 50 or so male demonstrators. But there were more supporters than detractors. It is also true that the intractable Hossein Shariatmadari of Kayhan has found 5 “lamentable” aspects of Rouhani’s trip and performance (including the way the President answered the Holocaust question, his reference to Israel instead of the Zionist regime, and of course, the phone call). But he has also had to defend himself against the charge of sounding more like Bibi Netanyahu than the Leader’s representative to the state-run newspaper.

No one expects Iranian opposition to the easing of tensions with the United States to go away. Over 4 million people voted for Saeed Jalili, Iran’s former nuclear negotiator deemed as the candidate who would continue Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s path. In fact, one of the anti-Rouhani demonstrators was identified as a senior worker on Jalili’s presidential campaign by a few websites. But there is also no denying that at least for now, the detractors are in the minority and mostly focused on the naïve nature of the current Rouhani policy and the presumed trust he may have in the possibility of real change.

They are preparing the ground for their “we told you so” six months from now. In the words of Mehdi Mohammadi, “then no one can say that not seeing the village chief is the problem. Now that they are sitting in front of the one they have called the village chief… If [the problem] is not resolved do we have the right to say that the problem lays elsewhere?”

This is why Obama is also intently watched in Iran. Most are hoping that he will sustain the unexpected fortitude he has shown while others are counting on his failure to overcome domestic and regional opposition to constructive bilateral talks to underwrite the ascent of their point of view that talking to the US is at best a pointless exercise.

Photo Credit: President Barack Obama talks with President Hassan Rouhani of Iran during a phone call in the Oval Office, Sept. 27, 2013. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

]]>by Ali Reza Eshraghi

Following the phone conversation between Presidents Barack Obama and Hassan Rouhani, the atmosphere in Iran has taken a happier turn while remaining surprisingly calm. Contrary to predictions made over the past week and during Rouhani’s trip to the UN, it appears the Iranian president has little problem in [...]]]>

by Ali Reza Eshraghi

Following the phone conversation between Presidents Barack Obama and Hassan Rouhani, the atmosphere in Iran has taken a happier turn while remaining surprisingly calm. Contrary to predictions made over the past week and during Rouhani’s trip to the UN, it appears the Iranian president has little problem in dealing with Iranian hardliners on his diplomatic approach with the USA. What exactly is happening here?

Upon arriving at Mehrabad airport in Tehran, a huge crowd of the president’s supporters welcomed him by slaughtering a sheep — a religious and cultural ritual of thanking god for the safe and successful return of travellers. They chanted, “Rouhani, Rouhani; thank you! thank you!” But, a few miles further down the road, a group of young hardliners known as Basijis or Hezbollahis stopped his car by chanting “Down with USA.” They accused Rouhani of crossing the regime’s redlines by negotiating with America and threw shoes and eggs at him.

In Iranian news media this unpleasant incident was reported only as a gathering of a hundred young protestors, an indicator that hardliners have lost their political influence in Iran for now. Only a few individual radical bloggers and hardline websites such as Rajanews, which is affiliated to the Paidari (Perseverance) Front and backed former chief nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili’s presidential bid criticized Rouhani for talking to Obama.

Unsurprisingly, Hossein Shariatmadari, the managing editor of the hardline Kayhan, described Rouhani’s action as “bad and evil.” Kayhan wrote that Rouhani hasn’t gained anything from the US “except a bunch of empty promises and an old Persian artifact which was stolen” — referring to the 2,700 year-old silver drinking cup which was returned to Iran last week.

Many Iranian political analysts consider Shariatmadari the mouthpiece of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. One of my colleagues, for example, sarcastically calls him the Supreme Leader’s Thomas Friedman.

But Kayhan was the only newspaper that criticized Rouhani on its front page while other Iranian dailies, even Javan — affiliated to Iran’s Revolutionary Guard (IRGC) and Resalat run by orthodox principlists — were mute.

Shariatmadari would probably be very happy to be known as the Supreme Leader’s voice to the public, but he is not alone. Khamenei has different mouthpieces with different functions and neither one represents his views precisely and completely.

For example, the former speaker of the Majlis, Gholam Ali Haddad Adel, whose daughter is married to the Supreme Leader’s son and ran against Rouhani in June’s presidential election, called Rouhani’s speech at the UN General Assembly smart and didn’t criticize his phone conversation with Obama, saying instead that “it can create an atmosphere for Iran to become more active in the international arena.”

To interpret the systematic reaction to Rouhani’s diplomacy with the US one should refer to the Friday prayer sermons across Iran, which were delivered only a few hours prior to the phone call. It is the Supreme Leader who directly appoints Friday prayer leaders and the political part of their sermons are dictated by an institution called the “Friday Prayer Leaders’ Policymaking Council,” also directly supervised by Khamenei. All Friday prayer leaders have unanimously praised the positions declared by the president during his New York trip.

The Friday prayer leader in the city of Mashahd, Ayatollah Ali Alamolhoda — known as a diehard hardliner — considered Rouhani’s words an example of “heroic leniency,” (an expression coined by the Supreme Leader). In legitimizing Rouhani’s actions Alamolhoda explained, “This administration has been successful in balancing its two responsibilities of safeguarding the honor of Islam [read the Iranian regime] and safeguarding the interests of Muslims [read the Iranian nation].”

Yet, one must not be surprised to hear “Down with USA” still being chanted at the same venue in which the lmams of the Friday prayer expressed their support for Rouhani. This paradox simply shows that contrary to what Iran experts say, the phone call will not suddenly end Iran’s domestic propaganda against America.

A considerable number of Iranian members of parliament, which is currently dominated by Principlist lawmakers, have supported Rouhani. This includes Mohammad Hossein Farhangi, a member of the Presiding Board who described the phone conversation “in line with national goals and interests and [in line with] the values of the Islamic revolution.” On the other hand, the powerful lawmaker Ahmad Tavakkoli warned that one should not become irrationally overexcited about this incident because “overexcitement is not in the interest of the Iranian nation and will reduce the bargaining power of Iranian authorities.”

The same goes for the Revolutionary Guards. Their commander, Major General Mohammad Ali Ja’fari, and the commander of the Qods Force (the international branch of the IRGC,) Qasem Soleimani, both have supported Rouhani’s diplomacy. On Saturday, the Sobh-e Sadeq weekly, which belongs to the IRGC, published its latest edition one day after the headline-making phone call. It had a very positive tone with regards to Rouhani’s behavior and described Rouhani’s op-ed piece in the Washington Post as “useful.” It also stressed that the IRGC will cooperate with Rouhani’s administration.

The IRGC’s positive reaction might force many analysts who believe the political and economic interests of the IRGC are against reducing tensions with the US to reconsider their positions. One must not forget that IRGC commanders have a behavior similar to the current Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, Martin Dempsey, who — despite initially warning against the dangers of US intervention in Syria — ultimately defended Obama’s strike proposal during a Senate hearing earlier this month.

Interestingly, both Iranians and Americans are asking the same question about the Rouhani-Obama phone conversation: who requested it? The Iranian side says the US was the one to initiate the call while the American side argues the opposite. This highlights the fundamental kinship between the two old adversaries in their mode of politicking.

The debate also extends to another issue that some Americans, such as Rep. Ed Royce (R-CA), Chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, believe: without sanctions, none of this would have happened. On the other hand, Iranians like Ahmad Tavakkoli believe it was Iran’s resistance against international pressure that has forced the US to enter talks with Iran.

Such debate seems ceaseless. But as of today it appears that Obama will have a more difficult time in convincing Congress to accept talks with Iran than Rouhani will in convincing Iranian hardliners. In a letter written in the the late 1980s to Revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani — who was Rouhani’s boss at the time — called for an end to the taboo of talks with the US. “Treading this pass will be difficult after you[r demise],” he wrote.

Now, twenty-four years after Khomeini’s death, Iranian politicians are smoothly treading this pass. It is wrong to think that Iran’s current Supreme Leader has suddenly made this decision. Just a year ago, around this time, Khamenei’s official website published commentary by Ayatollah Haeri Shirazi — the Supreme Leader’s former representative in the city of Shiraz — tacitly implying that supporters of the Supreme Leader must not be surprised by his decision for peace: “This is a test for the nation [to determine their] submission to the Leader.”

Except for a few figures who autonomously criticized Rouhani for his phone call with Obama, in the lower levels of Khamenei’s constituency all other supporters have taken to their social media networks to discuss the right or wrongfulness of this incident. Usually these discussions end with the justification that for the time being, they must remain silent and wait for the Supreme Leader’s explanation. As one famous Hezbollahi ring leader writes, “the most important things is following the “order of our master [Khamenei] whatever it may be.”

– Ali Reza Eshraghi was a senior editor at several of Iran’s reformist dailies. He is the Iran Project Manager at the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR) and a teaching fellow in the Department of Communication Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

– Photo Credit: Roohollah Vahdati/ISNA

]]>by Jim Lobe

Exactly three weeks ago, a confident Dennis Ross, President Barack Obama’s top Iran policy-maker for most of his first term, made the following assessments and predictions in an op-ed entitled, ironically, “Don’t Discount the Iranian Election:”

So now Ayatollah Khamenei has decided not to leave anything [...]]]>

by Jim Lobe

Exactly three weeks ago, a confident Dennis Ross, President Barack Obama’s top Iran policy-maker for most of his first term, made the following assessments and predictions in an op-ed entitled, ironically, “Don’t Discount the Iranian Election:”

So now Ayatollah Khamenei has decided not to leave anything to chance. …If there had been any hope that Iran’s presidential election might offer a pathway to different policy approaches on dealing with the United States, he has now made it clear that will not be the case. His action should be seen for what it is: a desire to prevent greater liberalization internally and accommodation externally.”

…Clearly, the Supreme Leader wanted to avoid the kind of excitement that Rafsanjani would have stirred up had he continued making public statements, as he has over the last two years, about Iran’s need to fix the economy and reduce Iran’s isolation internationally (a theme he has emphasized in recent years). But the exclusion of Rafsanjani from the election is also an important signal to anyone concerned about Iran’s nuclear program. If the Supreme Leader had been interested in doing a deal with the West on the Iranian nuclear program, he would have wanted [former President Akbar Hashemi] Rafsanjani to be president.

I say that …because if the Supreme Leader were interested in an agreement, he would probably want to create an image of broad acceptability of it in advance. Rather than having only his fingerprints on it, he would want to widen the circle of decision-making to share the responsibility. And he would set the stage by having someone like Rafsanjani lead a group that would make the case for reaching an understanding. Rafsanjani’s pedigree as Khomeini associate and former president, with ties to the Revolutionary Guard and to the elite more generally, would all argue for him to play this role.

…(T)he fact that the Iranian media is lavishing attention on [Saeed] Jalili certainly suggests that he is Khamenei’s preference, even though he has the thinnest credentials of the lot.

If Jalili does end up becoming the Iranian president, it will be hard to avoid the conclusion that the Supreme Leader has little interest in reaching an understanding with the United States on the Iranian nuclear program.”

Three weeks later, we know not only that Jalili did not win the election, but that the candidate backed with enthusiasm by both Rafsanjani and former reformist president Mohammad Khatami — Hassan Rouhani — did. Moreover, during his campaign, Rouhani did exactly what, in Ross’s assessment, made Rafsanjani’s candidacy unacceptable to Ali Khamenei: he spoke “about Iran’s need to fix the economy and reduce Iran’s isolation internationally…” — themes which he repeated in his 90-minute post-election press conference. In addition, Rouhani — given his 15 years on the Supreme National Security Council — appears to be an excellent vehicle for creating “an image of broad acceptability of [an agreement on Iran's nuclear program] in advance” if Khamenei were interested in such an accord. And, although he isn’t a former president like Rafsanjani, Rouhani’s reputed ability to bridge differences between conservatives, pragmatists and reformists would help Khamenei “widen the circle of decision-making to share the responsibility” of a deal. He would also be well placed to “lead a group that would make the case for reaching an understanding.”

Thus, if we assume, as Ross did three weeks ago, that Khamenei leaves nothing to chance and has the power to do so — a very questionable assumption among actual Iran experts (see here and here for examples) — then we might also see Jalili’s defeat and Rouhani’s surprise victory on what was essentially Rafsanjani’s platform as clear signals that Khamenei is indeed “interested in doing a deal on the Iranian nuclear program.” The only missing element in this scenario was Rafsanjani who, as noted above, strongly backed Rouhani and helped rally the centrists and reformists behind him. In light of Ross’s previous assessments regarding how the supreme leader signals his intentions on nuclear negotiations, would it be unreasonable to expect that Ross would not only be somewhat humbler with respect to his understanding of Iranian politics, but also rather hopeful about prospects for a real deal?

On the question of humility, the answer is not really, at least judging by his latest analysis, entitled “Talk to Iran’s New President. Warily.” Ross doesn’t even mention Jalili, Khamenei’s previously presumed chosen one. And while Ross seems genuinely puzzled by why Khamenei “allowed Mr. Rowhani to win the election,” particularly in light of the fact that the president-elect had “run against current [Khamenei-approved] Iranian policies,” he still sees the supreme leader as all-powerful, implying that Rouhani would not have won had Khamenei not approved of his victory.

As to the meaning of Khamenei’s permitting Rouhani to win, Ross floats four possible options, none of which, however, admits the possibility that Khamenei is prepared “to do a deal” acceptable to the West (a possibility for which Ross, just three weeks before, believed could have been signaled by the Guardian Council’s approval of Rafsanjani’s candidacy). He does entertain the possibility that Rouhani gained Khamenei’s approval for reasons related to the nuclear issue, but strictly for tactical purposes — not to reach a final accord that would preclude Iran’s attaining “breakout capability” (as would presumably have been possible if Rafsanjani had won the presidency):

He [Khamenei] believes that Mr. Rowhani, a president with a moderate face, might be able to seek an open-ended agreement on Iran’s nuclear program that would reduce tensions and ease sanctions now, while leaving Iran room for development of nuclear weapons at some point in the future.

He believes that Mr. Rowhani might be able to start talks that would simply serve as a cover while Iran continued its nuclear program.

Ross, who has been arguing for several months now that Washington needs to drop its approach of seeking incremental confidence-building accords with Iran in favor of making a final ultimatum-like offer (backed up by ever-tougher sanctions and ever-more credible threats of military action) that would permit Tehran to enrich uranium up to five percent (subject to the strictest possible international oversight in exchange for a gradual easing of sanctions), goes on to reject any let-up in pressure on Tehran.

Even if he were given the power to negotiate, Mr. Rowhani would have to produce a deal the supreme leader would accept. So it is far too early to consider backing off sanctions as a gesture to Mr. Rowhani.

We should, instead, keep in mind that the outside world’s pressure on Iran to change course on its nuclear program may well have produced his election. So it would be foolish to think that lifting the pressure now would improve the chances that he would be allowed to offer us what we need: an agreement, or credible Iranian steps toward one, under which Iran would comply with its international obligations on the nuclear issue.”[Emphasis added.]

Now, I, for one, find this reasoning difficult to understand. Ross may be right that external pressure was responsible for Rouhani’s election, but I suspect that it was a good deal more complicated than that, and, in any event, one of the last people I would seek out for an explanation as to why Rouhani won would be Ross, given his assessments of Iranian politics just three weeks ago. But to assert that easing pressure on Iran once Rouhani takes office (as a goodwill gesture) would somehow reduce the chances that Rouhani would be allowed to make concessions on the nuclear issue just doesn’t make much sense, if, for no other reason, virtually all Iran experts agree that Khamenei (and presumably hard-liners in and around his office) don’t believe Washington really wants an agreement because its ultimate goal is regime change. (Just today, Khamenei, while insisting that “resolving the nuclear issue would be simple” if hostile powers put aside their stubbornness, noted, “Of course, the enemies say in their words and letters that they do not want to change the regime, but their approaches are contrary to these words.”) If Khamenei is to be persuaded otherwise, Washington should work to bolster Rouhani and the forces that supported him in the election.

Indeed, most Iran specialists whose work I read argue that Rouhani’s election has really put the “ball in President Obama’s court”, as the International Crisis Group’s Ali Vaez wrote this week. They say that the response should not only be goodwill gestures, such as a congratulatory letter on his inauguration, but far more generous offers than what has been put on the table to date. Vali Nasr, for example, made the point last week when he argued that Rouhani “will likely wait for a signal of American willingness to make serious concessions before he risks compromise.”

For the past eight years, U.S. policy has relied on pressure — threats of war and international economic sanctions — rather than incentives to change Iran’s calculus. Continuing with that approach will be counterproductive. It will not provide Rowhani with the cover for a fresh approach to nuclear talks, and it could undermine the reformists generally by showing they cannot do better than conservatives on the nuclear issue.

…There is now both the opportunity and the expectation that Washington will adopt a new approach to strengthen reformists and give Rowhani the opening that he needs if he is to successfully argue the case for a deal with the P5+1.”

Paul Pillar made a similar point in the National Interest last week:

Rouhani’s election presents the United States and its partners with a test — of our intentions and seriousness about reaching an agreement. Failure of the test will confirm suspicions in Tehran that we do not want a deal and instead are stringing along negotiations while waiting for the sanctions to wreak more damage. …Passage of the test …means not making any proposal an ultimatum that is coupled with threats of military force, which only feed Iranian suspicions that for the West the negotiations are a box-checking prelude to war and regime change.”

“The Iranian electorate has in effect said to the United States and its Western partners, “We’ve done all we can. Among the options that the Guardian Council gave us, we have chosen the one that offers to get us closest to accommodation, agreement and understanding with the West. Your move, America.”

And, in contrast to Ross, who believes that time is fast running out and the “multilateral step-by-step approach …has outlived its usefulness,” the Brookings Institution’s Suzanne Maloney argued in Foreign Affairs that

To overcome the deep-seated (and not entirely unjustified) paranoia of its ultimate decision-maker, the United States will need to be patient. It will need to understand, for example, that Rouhani will need to demonstrate to Iranians that he can produce tangible rewards for diplomatic overtures. That means that Washington should be prepared to offer significant sanctions relief in exchange for any concessions on the nuclear issue. Washington will also have to understand that Rouhani may face real constraints in seeking to solve the nuclear dispute without exacerbating the mistrust of hard-liners.

In spite of this advice, things are moving in the opposite direction. On July 1, tough new sanctions to which Obama has already committed himself will take effect. Among other provisions, they will penalise companies that deal in rials or with Iran’s automotive sector. The Republican-led House is expected to pass legislation by the end of next month (that is, on the eve of Rouhani’s inauguration) that would sharply curb or eliminate the president’s authority to waive sanctions on countries and companies doing any business with Iran, thus imposing a virtual trade embargo on Iran. Other sanctions measures, including an anticipated effort by Republican Sen. Lindsay Graham to get an Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) resolution passed by the Senate after the August recess, are lined up.

It would be good to learn what Ross, who is co-chairing the new Iran task force of the ultra-hawkish Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs, thinks of these new and pending forms of pressure and whether they are likely to improve the chances that Rouhani will be able to deliver a deal.

]]>via IPS News

Iran’s June 14 presidential election results, announced the day after, was nothing less than a political earthquake.

The centrist Hassan Rowhani’s win was ruled out when Iran’s vetting body, the Guardian Council, qualified him as one of the eight candidates on May 21.

Furthermore, a first-round win [...]]]>

via IPS News

Iran’s June 14 presidential election results, announced the day after, was nothing less than a political earthquake.

The centrist Hassan Rowhani’s win was ruled out when Iran’s vetting body, the Guardian Council, qualified him as one of the eight candidates on May 21.

Furthermore, a first-round win by anyone in a crowded competition was not foreseen by any pre-election polling.

Until a couple of weeks ago, conventional wisdom held that only a conservative candidate anointed by Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei could win.

Few expected the election of a self-identified independent and moderate who was not well-known outside of Tehran.

And few thought participation rates of close to 73 percent were in the cards.

The expected range was around 60 to 65 percent, in favor of the conservative candidates who benefit from a solid and stable base of support that always comes out to vote.

But the move, a few days before the election by reformists and centrists — guided by two former presidents, Mohammad Khatami and Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani — to join forces and align behind the centrist Rowhani proved successful and promises significant changes in the management and top layers of Iran’s various ministries and provincial offices.

Rowhani has also promised a shift towards a more conciliatory foreign policy and less securitized domestic political environment.

The centrist-reformist alliance occurred when, in a calculated action earlier this week, the reformist candidate Mohammadreza Aref withdrew his candidacy in favor of Rowhani, whose campaign slogan was one of moderation and prudence.

But the strong support for Rowhani, underwriting his first-round win, was made possible by an unexpected surge in voter turnout.

A good part of the electorate, disappointed by Iran’s contested 2009 election and the crackdown that followed, had become skeptical of the electoral process and whether their vote would really be counted.

They also questioned whether the holder of any elected office now could make a difference in the direction of the country.

Low voter turnout was the expectation. But with the centrist-reformist alliance, the mood of the country changed.

Serious debate began everywhere, including in homes, streets, shops and electronic media, about whether to vote or not.

As more and more people became convinced, Rowhani’s chances increased. Hope overcame skepticism and cynicism.

The case for voting centered on the argument that the most important democratic institution of the Islamic Republic — the electoral process — should not be abandoned easily out of the fear that it will be manipulated by non-elective institutions.

Abandoning the field was tantamount to premature surrender, it was argued.

Reformist newspaper editorials also articulated the fear that a continuation of Iran’s current policies may lead the country into war and instability.

Syria, in particular, played an important role as the Iranian public watched a peaceful protest for change in that country turn into a violent civil war through the intransigence of Bashar al-Assad’s government and external meddling.

The hope that the Iranian electoral system could still be utilized to register a desire for change was a significant motivation for voters.

Beyond the choice of Iran’s president, the conduct of this election should be considered an affirmation of a key institution of the Islamic Republic that had become tainted when the 2009 results were questioned by a large part of the voting public.

The election was conducted peacefully and without any serious complaints regarding the process.

Unlike the previous election, when the results were announced hurriedly on the night of the election, the Interior Ministry, which is in charge of conducting the election with over 60,000 voting stations throughout the country, chose to take its time to reveal the results piecemeal.

Other key individual winners of this election, beyond Rowhani, are undoubtedly former presidents Hashemi Rafsanjani and Khatami who proved they can lead and convince their supporters to vote for their preferred candidate.

Khatami in particular had to rally reformers behind a centrist candidate who, until this election, had not said much about many reformist concerns, including the incarceration of their key leaders, Mir Hossein Mussavi, his spouse Zahra Rahnavard, and Mehdi Karrubi.

Khatami’s task was made easier when Rowhani also began criticizing the securitized environment of the past few years and the arrests of journalists, civil society activists and even former government officials.

Meanwhile, Hashemi Rafsanjani, whose own candidacy was rejected by the Guardian Council, sees his call for moderation and political reconciliation confirmed by Rowhani’s win.

He rightly sensed that, despite the country’s huge economic problems — caused by bad management and the ferocious US-led sanctions regime imposed on Iran — voters understood the importance of political change in bringing about economic recovery.

Conservatives, on the other hand, proved rather inept at understanding the mood of the country.

They failed in their attempt to unify behind one candidate and ended up stealing votes from each other instead.

The biggest losers of all were the hardline conservatives, whose candidate Saeed Jalili ran on a platform that mostly emphasized resistance against Western powers and a reinvigoration of conservative Islamic values.

Although he was initially believed to be the the favored candidate due to the presumed support he had from Khamenei, he ended up placing third, with only 11.4 percent of the vote, behind the more moderate conservative mayor of Tehran, Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf.

The hardliners loss did not, however, result from a purge. It is noteworthy that other candidates besides Rowhani received approximately 49 percent of the vote overall.

While this election did not signal the hardliners’ disappearance, it did showcase the diversity and differentiation of the Iranian public.

Rowhani, as a centrist candidate in alliance with the reformists, will still be a president who will need to negotiate with the conservative-controlled parliament, Guardian Council and other key institutions such as the Judiciary, various security organizations and the office of Leader Ali Khamenei, which also continues to be controlled by conservatives.

Rowhani’s mandate gives him a strong position but not one that is outside the political frames of the Islamic Republic.

He will have to negotiate between the demands of many of his supporters who will be pushing for a faster rate of change and those who want to retain the status quo.

His slogan of moderation and prudence sets the right tone for a country wracked by 8 years of polarized and erratic politics.

But Rowhani’s promises constitute a tall order.

Whether he will be able to lower political tensions, help release political prisoners, reverse the economic downturn and ease the sanctions regime through negotiations with the United States remains to be seen.

But Iran’s voters just showed they still believe the elected office of the president matters and expect the person occupying that office to play a vital role in guiding the country in a different direction.

Photo Credit: Mohammad Ali Shabani

]]>Talking to ordinary people in Neishabour and Tehran about Iran’s June 14 presidential election, economic issues seem foremost on their minds. But whom they will vote for is based on vague promises to pull the economy out of its deep crisis rather than well-defined economic programs.

Significant differences on economic philosophy divide [...]]]>

Talking to ordinary people in Neishabour and Tehran about Iran’s June 14 presidential election, economic issues seem foremost on their minds. But whom they will vote for is based on vague promises to pull the economy out of its deep crisis rather than well-defined economic programs.

Significant differences on economic philosophy divide a confused public about how to end economic stagnation and high inflation.

In the last three decades of the Islamic Republic’s history, Iranians have experienced both market-based economic growth and populist redistribution.

This election cycle would have been a good time to debate which of these two economic development strategies should be used in moving forward.

However, the decision by the Guardian Council to eliminate two important candidates, Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei, from the list of those eligible to run has sharply limited the value of this election as a space for vibrant public debate about the issues that are of greatest daily concern to most Iranians.

These two politicians could have represented the contrasting economic strategies and turned the election into a referendum on the past eight years of populist economics practiced by the Ahmadinejad administration.

Mr. Rafsanjani, the former two-time president, is well known for his preference for market-based economic growth as a solution to poverty and equity issues.

Early on in Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s tenure, Mr. Rafsanjani rejected Mr. Ahmadinejad’s populist policy of cash distribution as “fostering beggars.”

His elimination from this election has deprived voters of a critical assessment of Mr. Ahmadinejad’s populist program that has inflicted serious damage on Iran’s economy.

A further blow to a meaningful debate on populism came from the elimination of Mr. Mashaei, who was Mr. Ahmadinejad’s close associate and in-law.

It would have been highly interesting, if not very informative, to watch him debate Mr. Rafsanajani on such important issues as the record of the government’s three ambitious populist programs — low-interest loans to small and medium producers, low-cost housing and cash transfers.

What this election should be about is how to achieve a key promise of the Islamic Revolution.

More than three decades ago, a vast majority of Iranians supported the revolution, expecting that it would divide Iran’s oil wealth more equitably.

Early on, Ayatollah Khomeini, the revolution’s leader, tried to limit these expectations by famously saying that “economics is for donkeys.”

But the failure by two previous administrations (Mr. Rafsanjani and Mohammad Khatami, each serving for eight years as president) to reduce inequality has kept the issue of income and wealth distribution at the forefront in recent elections.

Mr. Ahmadinejad came to power in 2005 promising to take the “oil money to peoples’ dinner table,” which he tried to do.

The last two years for which we have survey data, 2010 and 2011, show falling poverty and inequality, but the economy is in shambles.

Prices rose by 40% last year according to official figures, and the same surveys show unemployment at about 15% overall and twice as high for youth.

It would have been valuable for the public to learn if Mr. Ahmadinejad’s redistribution policies are responsible for the current economic mess, or something else, like incompetence in execution or international sanctions.

What the candidates have said in the short time they have had to campaign is that they will do something different. What and how is not clear.

The four front-runners, Saeed Jalili, Mohammad-Baqer Qalibaf, Hassan Rowhani, and Ali Akbar Velayati, have expressed their differences on how to deal with sanctions.

Sanctions loom large in voter minds, but few believe that whoever is elected will be able to influence Iran’s nuclear policy, which is being tightly directed by the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

What seems to distinguish these candidates most clearly at this point is social rather than economic issues.

They all promise to reduce inflation, increase employment and run a less corrupt and more efficient administration. The differences exist in emphasis rather than specifics.

Mr. Jalili is the most conservative candidate in the race and closest to Mr. Ahmadinejad in economic philosophy but has also been careful to neither defend nor criticize the latter’s policies.

He has defended Iran’s stance in the nuclear negotiations with the P5+1 group (the U.S., Britain, France, China, and Russia plus Germany), which he led in recent years, with the usual anti-Western rhetoric.

By saying the least of any candidate about the economy, he has clearly indicated that economic issues are not his top priority.

In the televised debates, Mr. Jalili made it clear that a more effective enforcement of cultural values was the right way to solve the country’s economic problems.

More specifically, he seemed to reject compromising with the West over Iran’s nuclear program in order to lessen the pain of Western sanctions on ordinary Iranians.

If Mr. Jalili is Mr. Ahmadinejad’s favorite candidate, Mr. Ahmadinejad has not said anything.

He has not made any public statement regarding the candidates so far, except to request time on national television to respond to their criticisms, which was denied.

Word on the street in Tehran is that Mr. Ahmadinejad secretly roots for Mr. Jalili because he believes a President Jalili would be the most likely to make him look good, not by defending his policies, but by taking the economy further into the deep end.

Mr. Rowhani, the only cleric in the race, is the most moderate candidate among the four front-runners.

In the eyes of liberal voters, following this week’s departure of reformist candidate Mohammad-Reza Aref (after an explicit request from the popular former president, Mohammad Khatami), Mr. Rowhani has inherited the reformist mantle of Mr. Khatami as well as Mr. Rafsanjani’s pro-business legacy.

Mr. Rowhani energized Iran’s young voters after the second televised debate in which he criticized the heavy hand of security forces in social affairs.

He appears to have gained the same lift that former presidential candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi achieved four years ago upon declaring he would end police enforcement of public chastity.

However, like Mr. Mousavi, Mr. Rowhani has not offered clear economic policies to address the youth’s more serious problems of unemployment and family formation.

A formidable challenge to Mr. Rowhani comes from Mr. Qalibaf, the current mayor of Tehran and a moderate conservative.

During a recent televised debate, they clashed over how the police should treat student protests, but they have not tried to distinguish themselves on how they would help university graduates get jobs.

If the election goes to a second round run-off between these two candidates, which now seems likely, there is a chance that voters will hear more about their approach to revive the economy.

But then the candidates may find it easier to appeal to voters’ emotions than to their pocketbooks.

Photo: The campaign headquarters of presidential hopeful Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf in the Iranian city of Neishabour. Credit: Djavad Salehi-Isfahani

]]>by Farideh Farhi

I read with great interest the writing of Washington’s new Iran expert, Dennis Ross. With a title like “Don’t Discount the Iranian Election”, I thought, wow! Iran’s contested and improvised politics are finally being taken seriously. What else could that mean other than an acknowledgment that [...]]]>

by Farideh Farhi

I read with great interest the writing of Washington’s new Iran expert, Dennis Ross. With a title like “Don’t Discount the Iranian Election”, I thought, wow! Iran’s contested and improvised politics are finally being taken seriously. What else could that mean other than an acknowledgment that there is politics in Iran, including strategizing by the significant players and the organized and even unorganized forces within the power structures that impact policy choices?

But Ross’s piece is not about competing views of how to run the country, nor is it about Iran. It is all about us.

Iran’s June 14 presidential election has already been engineered by its master designer, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, to send the message that “he has little interest in reaching an understanding with the United States on the Iranian nuclear program.” This, Ross states, “If [Saeed] Jalili does end up becoming the Iranian president.” But he fails to tell us what message Khamenei will send if someone besides Jalili is elected and doesn’t even entertain the possibility that the ballot box results may not be pre-determined — that people might, just might, have something to do with this.

After all, Iranian politics is either about big changes or no changes at all. It is also apparently shaped by one man who knows what he wants, but has to wait for an election to send his message to the US.

Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani failed in his attempt to challenge Khamenei’s authority and now there are no individuals or forces independent of Khamenei remaining. To boot, Khamenei is so independent that he is not moved by anything in society. Everything is generated from his head and his head alone. Like all imagined Oriental despots, Khamenei alone now holds agency in Iran.

The possibility that this election may involve a degree of competition among factions or circles of power, with a good part of the population still undecided about whether to participate or which candidate to vote for, is not even permitted. After all, the “freedom-loving people of Iran” also only have two modes. They either move in unison to protests in the streets or are cowed, again in unison, by the dictates and batons of one man and his cronies. In the first scenario we love them all and in the second we pity them; but in both cases we view them as a herd that occasionally may — at least we hope — stampede toward the goal of what we have.

You’d think that after more than a decade of disastrous policy choices based on the belief that Middle Eastern countries are run by one intractable man, Washington experts would have developed some humility in forwarding their Orientalist presumptions as analysis. But not even ten years of disastrous policies following repeated declarations of so-and-so must go — the last one uttered by President Obama against Bashar al-Assad nearly two years ago — has resulted in any qualms about reducing the complex politics of a post-revolutionary society, which from the beginning has been shaped and reshaped by factions and factional realignments, to a clash of titans invariably moving towards despotism.

What Happened Last Time

Yes, I am aware of what happened in 2009 and even before, when the creeping securitization of the Iranian political system was already well under way, based on both the exaggerated pretext and real fear of external meddling. And yes, I know there is an intense debate among the critics and opposition, be they the reformists or the Green Movement. Activism does not only take place in the streets, it also happens in conversations regarding whether to vote or not.

Given the dynamic state-society relations of the Islamic Republic and societal demands that clearly remain unfulfilled, it would be quite unnatural if at least some parts of Iran’s vibrant, highly urbanized and differentiated society did not debate the legitimacy, role and weight of the electoral system as an integral institution of the Islamic Republic’s identity after what happened in 2009.

This election is deemed important by some and meaningless by others depending on the assessment of the extent to which the masterminds of the 2009 so-called “electoral coup” have managed to consolidate power. But even on the issue of what voting means and whether it will legitimize the Islamic Republic there exists a mostly reasoned debate and conversation. It is a debate and conversation because many people are trying to convince both themselves and their interlocutors that they’re making the right choice. Whatever they decide, they want their action to have political meaning.

Why The Presidential Debates Matter

Another debate also exists within the frames of the available competition. Is there a difference among the candidates in terms of proposed policies? In this conversation, the cynics don’t think that a decision not to vote will undermine the Islamic Republic. Like their counterparts in many other countries, they believe that despite the different rhetoric and promises, the candidates will all end up the same; nothing will change.

But there are also those who are watching for a reason to vote. For some perhaps because a candidate appeals to them. For others, because a candidate scares them.

Iran’s state television recently announced that about 45 million out of a population of 75 million have been watching the presidential debates, the third of which on politics and foreign policy was just held. The interest-level was so high that state TV announced a potential fourth debate.

Perhaps the viewership number has been exaggerated to give the impression of a heated election, but given the conversation I am following on blogs and websites with different viewpoints, it is hard to dispute that many people have been watching.

I’ve always wondered why Iran’s presidential debates have attracted so many viewers. I was in Iran in 1997 when the first debates were held among only four candidates. I had been to Mohammad Khatami’s rallies and knew about his ability to woo through words. What made him difficult to resist as a candidate was precisely the different way he spoke to attract voters. In a country where — in both the monarchist and Islamist eras — what the voter must or should do has always been uttered in every other sentence, a presidential candidate with the art of conversation was something to behold for me. People told me I was crazy and Khatami had no chance. The system would not allow it. But when Khatami came on television and began to talk, things changed.

This isn’t romantic nostalgia. The fundamental changes that have occurred in the relationship between politicians and citizens in Iran can be detected in the way they talk to each other. Iranian clerics have always been good talkers; they know their flock. But finding a language to woo voters is something different.

What’s Happening Now

Just consider what happened in the first presidential debate last week. The highly stilted and child-like format — designed to ensure that the conversation did not spiral out of control — was immediately challenged by the reformist candidate, Mohammadreza Aref, and a couple of others who followed him.

Afterwards the debate was criticized by all the participants and became a subject of both scorn and delicious humor everywhere. The integrity of the institution that held the debate came under question, some said. Others declared the nation had been insulted, the office of the president as a whole denigrated. We are not in kindergarten; treat the audience like adults, the critics shouted.

Iran’s state-run TV effectively was forced to change the format by the second debate, but it was in the third debate that the dam broke and real conversation began on no less a topic than Iran’s handling of its nuclear dossier.

People were somewhat expecting this. Two secretaries of the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) and nuclear negotiators — one former and one current — are, after all, running.

Current negotiator Saeed Jalili has nothing in his portfolio other than his handling of Iran’s nuclear file in negotiations with the five permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany (P5+1), so the framing of his candidacy in terms of his handling of the talks could not be avoided.

But Jalili had to face someone who could not afford to accept his narrative — former negotiator Hassan Rowhani — since Rowhani’s own record is also somewhat tied to nuclear diplomacy. It was an intense conversation with little held back — not about whether Iran should enrich uranium or not, as the discussion is framed in the United States — but about which nuclear negotiating team has been more successful in its interactions with the West. Both played offense and defense.

During Friday’s debate, however, it was not the two nuclear negotiators who broke the dam. It was Ali Akbar Velayati, the former foreign minister and Khamenei’s current senior adviser on foreign affairs. Reacting to Jalili’s certitude over his conduct and disdain for the appeasement of Rowhani’s team, Velayati let loose his criticism of Jalili’s performance by saying, “reading statements does not make diplomacy.” Then Velayati explained to the audience that twice in the past 8 years, attempts to resolve the nuclear issue through negotiations were sabotaged by Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and the foreign ministry. Other candidates followed him, pointing to the lack of success of the current nuclear team.

This is not to say that Jalili demurred. He defended himself and also attacked, rejecting Velayati’s portrayal of his negotiating skills and telling the audience about the shabby way Rowhani’s team was treated by its Western counterparts, egged on by the United States. To prove his point, Jalili even read from Rowhani’s book, which details his negotiations with the EU, UK, France and Germany. Iran gave in and suspended, and the Westerners became louder in their demands, said Jalili. More significantly, Jalili did not talk like anyone’s man; he talked like a believer.

Rowhani did not run away from the conversation either. He’s a believer in his own approach too and disdainful of Jalili’s way — as is Velayati.

Keep in mind that the debates’ audiences don’t watch with a unified eye. Iran, like elsewhere, is not a country with only two abstract actors: “regime” and “people.” There are many people who agree with Jalili regarding the failure of Rowhani’s nuclear team and continue to rally together around this issue. There are also some who identify with his representation of himself as remaining true to being a basiji, or dedicated and lowly soldier of the system.

Then there are those who are genuinely fearful of a Jalili presidency. But even this fear is not expressed in a unified fashion.

Some are petrified by the potential for another 8 years of inept management. I make no claim in knowing who supports Jalili’s candidacy — and would be skeptical of anyone claiming to know. But I can read the websites that support his candidacy. And his potential cabinet ministers look awfully like Ahmadinejad’s ministers.