by Derek Davison

As talks aimed at a comprehensive nuclear deal with Iran continue, with principals from Iran and world powers meeting in Vienna this week, two recent analyses of the negotiations have compared the talks to a “Rubik’s Cube.”

A May 9 report from the International Crisis Group [...]]]>

by Derek Davison

As talks aimed at a comprehensive nuclear deal with Iran continue, with principals from Iran and world powers meeting in Vienna this week, two recent analyses of the negotiations have compared the talks to a “Rubik’s Cube.”

A May 9 report from the International Crisis Group (ICG) entitled, “Iran and the P5+1: Solving the Nuclear Rubik’s Cube,” offers 40 recommended action items that Iran and the P5+1 (the US, UK, France, China and Russia plus Germany) could agree to implement in a comprehensive deal. Today the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) also held a panel discussion called, coincidentally, “The Rubik’s Cube of a Final Iran Deal,” moderated by Colin Kahl, the top Middle East policy official at the Defense Department for most of Obama’s first term, and featuring Robert Einhorn, who served as the State Department’s special advisor on non-proliferation and arms control until less than a year ago, Joe Cirincione, the president of the Ploughshares Fund, and Alireza Nader, an Iran expert at the RAND Corporation.

There’s a clear sense in both analyses that a deal is reachable. Cirincione rightly pointed out at the USIP event that the current talks are “the closest we’ve come to an agreement, ever,” and predicted that “absent some unforeseen event, we are going to get a deal.” Indeed, the very existence of something like the ICG report, a specific and detailed look at what a deal might actually contain, would have appeared presumptuous even six months ago but now seems very reasonable given the progress that has already been made.

However, optimism aside, a great deal of work still needs to be done before a deal can be finalized. The level of detail contained in the ICG report speaks to the complexity involved in the negotiations. The ICG recommends, for example, an immediate cap on Iranian uranium enrichment of 6400 Separative Work Units (SWU, a measurement of enrichment capacity that incorporates both the number and technological advancement of operational centrifuges) per year, which is a steep cut from Iran’s current 9000 SWU/year capacity (that Iran sees as already too low), and one that the Iranians may be unwilling to make. That cap would then be lifted, over 8-10 years, to around 19,000 SWU/year, an increase that could theoretically reduce the time it would take Iran to manufacture a nuclear weapon if it chose to pursue that goal. Of course, it remains to be seen whether Iran and the P5+1 would agree to those terms.

The ICG framed its recommendations around four points:

- constraining any Iranian capacity to build a nuclear weapon;

- implementing a stringent monitoring and verification system on Iran’s nuclear program,

- establishing concrete negative consequences for a breach of the deal by either side;

- and establishing positive consequences for compliance.

But the ICG’s recommendations, and the discussion on the USIP panel, make it very clear that these objectives will be difficult to meet in a way that satisfies both parties. The two sides disagree on even basic elements of the talks; as Kahl explained, the Iranian government rejects the P5+1’s continued focus on Iranian “breakout capacity” because it has officially sworn off of any military application of its nuclear program. The P5+1 does not accept those assurances, but Iran also has legitimate questions as to why other countries with civilian nuclear programs have not been subject to the same requirements that Iran has faced.

The USIP panel seemed to reach a general consensus that the biggest remaining hurdles to a comprehensive deal revolve around Iran’s uranium enrichment program. This includes both Iran’s capacity for enrichment and the amount of enriched uranium it will be allowed to stockpile; the level of access that Iran will permit to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and its inspectors; and the timing of and conditions for sanctions relief.

The P5+1 are seeking to maximize the limits on Iran’s nuclear program and the IAEA’s access to Iranian nuclear sites while maintaining sanctions at a high level for a considerable period of time, perhaps decades. Iran, obviously, is seeking the opposite – minimal limits on its nuclear program in return for considerable sanctions relief and only a short period in which its program is subject to international monitoring. As the ICG report put it, “it would appear that the P5+1’s maximum — in terms of both what it considers a tolerable residual Iranian nuclear capability and the sanctions relief it is willing to provide — falls short of Iran’s minimum.”

The single biggest complication to these talks is the utter lack of trust on both sides. As Nader argued, mutual trust is not a requirement for success and the lack of trust can be worked around with stringent inspections requirements and firm commitments to agreed-upon sanctions relief. But that lack of trust adds considerable complexity and difficulty to the negotiations. Iran is ultimately being asked to prove a negative, that it has no nuclear weapons program, and because the P5+1 do not trust Iran to uphold its promises, demands for monitoring requirements and caps on nuclear capacity may simply be too much for Iran to accept.

This is particularly true given a domestic political environment that Nader termed “poisonous,” with Iranian hardliners increasingly concerned about President Hassan Rouhani’s commitment to protecting Iran’s interests in these negotiations, and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s support for the talks vulnerable to shifting political winds.

Iran will also have difficulty trusting the P5+1 to uphold its end of a deal to reduce sanctions assuming that Iran meets, and continues to meet, its obligations. Indeed, Cirincione pointed out today out that western banks, fearful of running afoul of sanctions laws, have still not released the Iranian assets that were unfrozen under the terms of last November’s “Joint Plan of Action.” The challenge of getting a final deal through a potentially hostile US Congress, particularly in an election year, could also give Iran reason for concern.

Yet failed talks could be disastrous for both sides, according to the ICG. Failure now would make another attempt at negotiations very unlikely, would result in new punitive measures against Iran (including new sanctions on an already sputtering economy, and potential military strikes on Iranian nuclear sites), and could ultimately push Tehran to rush for a nuclear weapon, something which everyone, including Iran, says they don’t want.

]]>via USIP

Iran has mixed feelings and conflicting interests in the Syrian crisis. Tehran has a strategic interest in opposing chemical weapons due to its own horrific experience during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. For years, President Saddam Hussein’s military used chemical weapons that killed thousands of Iranian soldiers. So [...]]]>

via USIP

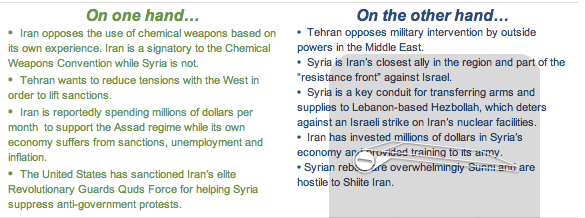

Iran has mixed feelings and conflicting interests in the Syrian crisis. Tehran has a strategic interest in opposing chemical weapons due to its own horrific experience during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. For years, President Saddam Hussein’s military used chemical weapons that killed thousands of Iranian soldiers. So Iran actually shares interests with the United States, European nations and the Arab League in opposing any use of chemical weapons.

But the Islamic Republic also has compelling reasons to continue supporting Damascus. The Syrian regime is Iran’s closest ally in the Middle East and the geographic link to its Hezbollah partners in Lebanon. As a result, Tehran vehemently opposes U.S. intervention or any action that might change the military balance against President Bashar Assad.

The Iran-Syria alliance is more than a marriage of convenience. Tehran and Damascus have common geopolitical, security, and economic interests. Syria was one of only two Arab nations (the other being Libya) to support Iran’s fight against Saddam Hussein, and it was an important conduit for weapons to an isolated Iran. Furthermore, Hafez Assad, Bashar’s father, allowed Iran to help create Hezbollah, the Shiite political movement in Lebanon. Its militia, trained by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, has been an effective tool against Syria’s archenemy, Israel.

Relations between Tehran and Damascus have been rocky at times. Hafez Assad clashed with Hezbollah in Lebanon and was wary of too much Iranian involvement in his neighborhood. But his death in 2000 reinvigorated the Iran-Syria alliance. Bashar Assad has been much more enthusiastic about Iranian support, especially since Hezbollah’s “victorious” 2006 conflict with Israel.

In the last decade, Iran’s Revolutionary Guards have trained, equipped, and at times even directed Syria’s security and military forces. Hundreds of thousands of Iranian pilgrims and tourists visited Syria before its civil war, and Iranian companies made significant investments in the Syrian economy.

Fundamentalist figures within the Guards view Syria as the “front line” of Iranian resistance against Israel and the United States. Without Syria, Iran would not be able to supply Hezbollah effectively, limiting its ability to help its ally in the event of a war with Israel. Hezbollah wields thousands of rockets able to strike Israel, providing Iran deterrence against Israel — especially if Tel Aviv chose to strike Iran’s nuclear facilities. A weakened Hezbollah would directly impact Iran’s national security. Syria’s loss could also tip the balance in Iran’s rivalry with Saudi Arabia, making the Wahhabi kingdom one of the most influential powers in the Middle East.

In the run up to a U.S. decision on military action against Syria, Iranian leaders appeared divided.

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and hardline lawmakers reacted with alarm to possible U.S. strikes against the Assad regime. And Revolutionary Guards commanders threatened to retaliate against U.S. interests. The hardliners clearly viewed the Assad regime as an asset worth defending as of September 2013.

But President Hassan Rouhani, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif and former President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani adopted a more critical line on Syria. “We believe that the government in Syria has made grave mistakes that have, unfortunately, paved the way for the situation in the country to be abused,” Zarif told a local publication in September 2013.

Rafsanjani, still an influential political figure, reportedly said that the Syrian government gassed its own people. This was a clear breach of official Iranian policy, which has blamed the predominantly Sunni rebels. Rafsanjani’s words suggested that he viewed unconditional support for Assad as a losing strategy. His remark also earned a rebuke from Khamenei, who warned Iranian officials against crossing the “principles and red lines” of the Islamic Republic. Khamenei’s message may have been intended for Rouhani’s government, which is closely aligned with Rafsanjani and seems to increasingly view the Syrian regime as a liability.

Regardless, a significant section of Iran’s political elite could be amenable to engaging the United States on Syria. Both sides have a common interest: preventing Sunni extremists from coming to power in Damascus. Iran and the United States also prefer a negotiated settlement over military intervention to solve the crisis. Tehran might need to be included in a settlement given its influence in Syria. Negotiating with Iran on Syria could ultimately help America’s greater goal of a diplomatic breakthrough, not only on Syria but Tehran’s nuclear program as well.

– Alireza Nader is a senior international policy analyst at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation.

*Read Alireza Nader’s chapter on the Revolutionary Guards in “The Iran Primer”

Photo Credits: Bashar Assad and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei via Leader.ir, Syria graphic via Khamenei.ir Facebook

]]>via USIP

Iranian politics are personal. Indeed, the theocrats are decidedly earthly in their rivalries. But the 2013 election is particularly telling. It may be settling a score dating back a quarter century between the revolution’s two most enduring politicos—Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and former President [...]]]>

via USIP

Iranian politics are personal. Indeed, the theocrats are decidedly earthly in their rivalries. But the 2013 election is particularly telling. It may be settling a score dating back a quarter century between the revolution’s two most enduring politicos—Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and former President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani.

The two men have competed for power and the right to define the revolution since the death of revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1989. Rafsanjani originally had the upper hand in two sweeping changes. He oversaw constitutional changes that created an executive president, which he then ran for and won. And, in Tehran’s worst-kept secret, he orchestrated Khamenei’s selection as the new supreme leader, reportedly because Khamenei was a middle-ranking cleric and dour figure who could not rival Rafsanjani’s political base or charismatic wiles. Khamenei actually owes his power and position to Rafsanjani, the man known in Iran as the “shark.”

But since 1989, Rafsanjani’s master plan has gradually unraveled. In 2013, Khamenei has now managed not only to emerge from Khomeini’s shadow. He has also sidelined most of his old rivals, including the crafty Rafsanjani. On May 21, Rafsanjani was disqualified from running for the presidency—even though the 12-man Guardian Council had qualified him to run in three earlier elections. He had been elected twice. Rafsanjani is 78. Winning elected political office is likely to be increasingly difficult. Hardliners in parliament even considered legislation this year that would bar any candidate over the age of 75.

For now, Khamenei is his own man. Yet the two rivals still epitomize a core schism among the original revolutionaries.

Rafsanjani believes Islam should be the basis of Iran’s political system. But he also advocates facets of modern politics, including republican institutions, an essentially capitalist economy, and a foreign policy that honors international practices. It is not liberal democracy. It instead has electoral outlets with strict safeguards that protect religious and revolutionary doctrines. Rafsanjani appears to view himself as a modern day version of Amir Kabir, the reformist chief vizier for Qajar dynasty Naser al Din Shah in the 19th century.

In contrast, Khamenei is more conservative and dogmatic. He believes that the supreme leader, rather than the president, should be the theocracy’s key decision-maker. He also appears to view the Iranian people more as subjects than citizens. For Khamenei, the supreme leader’s authority is primarily derived from God and the Hidden Imam. Elected institutions are meant to implement his policies rather than shape them.

Khamenei has spent the last 24 years converting his vision into a reality—and taking on his revolutionary peers. Between 1989 and 1997, he tolerated President Rafsanjani’s economic liberalization and attempted détente with the West because he had little choice as a newly minted leader. But he used the time to build his own power base, tapping into close connections to the Revolutionary Guards. He had served as their supervisor and deputy minister of defense during the revolution’s first decade and the tough eight-year war with Iraq.

Once Rafsanjani’s term was over, Khamenei used the Guards to suppress reformists under President Mohammad Khatami, who held office for two terms between 1997 and 2005. Khamenei was widely believed to feel threatened by Khatami, a suave cleric who had popular appeal and a historic connection to Khomeini. Like Rafsanjani, Khatami was also thwarted from running again in the 2013 presidential election.

Khamenei’s initial support for Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who first ran for the presidency in 2005, was partly because the Tehran mayor’s had no connections to Khomeini. He was also not a cleric with religious standing that could undermine the supreme leader. The other two major candidates in the disputed 2009 presidential race — Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi — had both been close to Khomeini. As prime minister from 1981 to 1989, Mousavi had frequently clashed with Khamenei at a time Iran had a parliamentary government and Khamenei was titular president. Karroubi had been head of the Imam Khomeini Relief Committee and the Martyr’s Foundation as well as speaker of parliament. Both men are now under house arrest for challenging the 2009 election and serving as leaders of the so-called “sedition” against Khamenei’s rule.

Khamenei has managed to clear the field. Yet his position at the top is also lonely and potentially unwieldy.

Ironically, Iran’s supreme leader now faces opposition from an unexpected source — the family of the only other man who held the job. Khomeini’s daughter recently published an open letter to Khamenei stating that her father wanted Iran to be ruled by Khamenei and Rafsanjani working side-by-side. She warned that Rafsanjani’s removal from power would make the regime a dictatorship — and could even imperil the revolution.

– Alireza Nader is a senior policy analyst at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation and the author of “Iran After the Bomb.”

]]>via USIP

On April 22, Canadian authorities arrested two men who allegedly planned to derail a U.S.-bound passenger train. Officials said al Qaeda elements in Iran gave “direction and guidance” to Chiheb Esseghaier, 30, and Raed Jaser, 35. But police have not found evidence of Iranian state sponsorship. And Tehran [...]]]>

via USIP

On April 22, Canadian authorities arrested two men who allegedly planned to derail a U.S.-bound passenger train. Officials said al Qaeda elements in Iran gave “direction and guidance” to Chiheb Esseghaier, 30, and Raed Jaser, 35. But police have not found evidence of Iranian state sponsorship. And Tehran has denied any connection to the plot.

What has been the relationship between Iran and al Qaeda?

Iran and al Qaeda have had a complex and rocky relationship for two decades. The Shiite theocracy and the Sunni terrorist organization are not natural allies. Al Qaeda’s hardline Salafi/Wahhabi interpretation of Islam believes that Shiites are heretics. In 2009, a leader of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula proclaimed that Shiites, particularly Iranians, posed more of a danger to Sunnis than Jews or Christians. Iran has likewise been hostile toward al Qaeda and its former Taliban hosts in Afghanistan.

But countries and movements with seemingly inimical views can work together when circumstances warrant. The 9/11 Commission reported that Iran and al Qaeda contacts go back two decades, beginning when Osama bin Laden was based in Sudan. The report also noted “strong but indirect evidence” that al Qaeda played “some as yet unknown role” in the 1996 bombing of the Khobar Towers, a U.S. military barracks in Saudi Arabia, by the Iran-supported Saudi Hezbollah. A number of the 9/11 hijackers traveled through Iran to Afghanistan, although there is no evidence that Tehran was aware of the plot.

Some of the best information available on the al Qaeda-Iran relationship was found during the May 2011 raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. Documents “show that the relationship is not one of alliance, but of indirect and unpleasant negotiations over the release of detained jihadis and their families, including members of Bin Laden’s family,” according to the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. “The detention of prominent al Qa`ida members seems to have sparked a campaign of threats, taking hostages and indirect negotiations between al-Qa`ida and Iran that have been drawn out for years and may still be ongoing.”

Iran and al Qaeda are clearly at odds in the Syrian civil war. Bashar Assad’s regime is Iran’s key Arab ally, and Tehran is expending considerable effort to prop up Damascus. Al Qaeda, on the other hand, has joined the anti-Assad insurgency. Ayman al Zawahiri, Osama bin Laden’s successor, has urged fighters from around the region to join the battle against Assad. The Nusra Front, one of Syria’s strongest rebel groups, recently pledged its allegiance to al Qaeda.

Are there known al Qaeda elements in Iran? Where?

Hundreds of al Qaeda fighters in Afghanistan fled west to Iran after the U.S.-led coalition intervention in October 2001, and many were detained by Iranian authorities in eastern Iran, near the Afghanistan and Pakistan border. Iran claims to have extradited more than 500 to their home countries in the Middle East, Africa and Europe.

Some high-profile detainees, including top al Qaeda strategist Saif al Adel and Osama bin Laden’s son-in-law Sulaiman Abu Ghaith, were held with their families under house arrest in Iran, possibly as insurance against al Qaeda attacks on Iranian interests or for use as bargaining chips. Al Adel and Abu Ghaith were given greater freedom to travel in exchange for the 2010 release of an Iranian diplomat who had been held in Pakistan’s tribal areas. Abu Gaith was captured in Jordan by the United States in February 2013.

It’s unclear how close an eye Iranian security services are keeping on al Qaeda elements currently living in eastern Iran. The remote area along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border is sparsely populated and home to the Baloch ― a Sunni ethnic group that has waged a decades-long insurgency against Pakistan and Iran. A 2011 U.S. Treasury Department report accused Tehran of having a secret deal with al Qaeda that allows the group to funnel funds and operatives through Iranian territory. But the report did not cite Iranian officials for complicity in terrorism.

Canadian police said there is no evidence of Iranian sponsorship so far. What is known about Iran’s role?

It would mark a shift in strategy if Iran was actively involved in the planning of al Qaeda attacks. Canadian officials have claimed that al Qaeda leaders in Iran gave the two men considerable independence in planning and carrying out the alleged plot. The Iranian government probably would not have allowed them that operational freedom. Based on the evidence released by Canada, Tehran was probably not involved in any significant way.

The costs would not have been worth the benefits to Iran either. Any proven Iranian role in a terrorist attack that derailed a passenger train would have further strengthened international opinion against Tehran. It is already isolated and faced with many layers of economic sanctions. The timing is also awkward. Iranian complicity could jeopardize negotiations over its controversial nuclear program with the United States and five major world powers. At the same time, Iranian strategy has been opaque even to those who have observed Iran for decades.

– Matthew Duss is a policy analyst at the Center for American Progress.

- Photo: Al-Qaida leaders Ayman al-Zawahri, Osama bin Laden and Suleiman Abu Ghaith in 2002.

]]>via USIP

What steps would be necessary for Iran to build a nuclear weapon?

President Obama has estimated that it would take Iran “over a year or so” for Iran to develop a nuclear weapon. But that device would likely be crude and too large to fit on [...]]]>

via USIP

What steps would be necessary for Iran to build a nuclear weapon?

President Obama has estimated that it would take Iran “over a year or so” for Iran to develop a nuclear weapon. But that device would likely be crude and too large to fit on a ballistic missile. Producing a nuclear weapon that could be launched at Israel, Europe, or the United States would take substantially longer. Iran would need to complete three key steps.

Step 1: Produce Fissile Material

Fissile material is the most important component of a nuclear weapon. There are two types of fissile material: weapons-grade uranium and plutonium. Tehran has worked primarily on uranium. There are three levels or enrichment to understand the controversy surrounding Iran’s program:

·90 percent enrichment: The most likely route for Iran to produce fissile material would be to enrich its growing stockpile of low-enriched uranium to 90 percent purity —or weapons-grade level. Western intelligence agencies suggest Iran has not decided to enrich uranium to 90 percent.

·3.5 percent enrichment: As of early 2013, Iran had approximately 18,000 pounds of “low-enriched uranium” enriched to the 3.5 percent level (the level used to fuel civilian nuclear power plants). This stockpile would be sufficient to produce up to seven nuclear bombs, but only if it were further enriched to weapons-grade level (above the 90 percent purity level). Experts estimate Iran would need at least four months to produce enough weapons-grade uranium for one bomb using 3.5 percent enriched uranium as the starting point.

·20 percent enrichment: In early 2013, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the U.N. watchdog group that inspects Iranian nuclear facilities, said Iran also had a stockpile of 375 pounds of 20 percent low-enriched uranium, ostensibly to provide fuel for a medical research reactor. This stockpile is about two-thirds of the 551 pounds needed to produce one bomb’s worth of weapons-grade material if further enriched. If Iran accumulated sufficient quantities of 20 percent low-enriched uranium, it might be able to enrich enough weapons-grade uranium for a single bomb in a month or two.

The main issue is the status of the uranium enriched to 20 percent and the two production sites—at the Fordo plant outside the northern city of Qom and the Natanz facility in central Iran. U.N. inspectors visit these sites every week or two, however, so any move to produce weapons-grade uranium in an accelerated timeframe as short as a month would be detected. Knowing this, Iran is unlikely to act.

The speed of enrichment also depends on the centrifuges used, both their number and their quality. For a long time, Iran had used thousands of fairly slow IR-1 centrifuges to spin and then separate uranium isotopes. But since January 2013, it has started to install IR-2M centrifuges, which spin three to five times faster. In early 2013, Tehran claimed to be using about 200 IR-2Ms at the Natanz site.

Tehran might be able to enrich enough uranium for one bomb ― from 20 percent purity to 90 percent ― in as little as two weeks if it installs large numbers of advanced IR-2M centrifuges. Iran has announced its intention to eventually install as many as 3,000.

Step 2: Develop a Warhead

Iran would next have to build a nuclear device. It would need to build a warhead based on an “implosion” design if Iran wanted to deliver a nuclear device on a missile. It would include a core composed of weapons-grade uranium (or plutonium) and a neutron initiator surrounded by conventional high explosives designed to compress the core and set off a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction.

IAEA documents claim, “Iran has sufficient information to be able to design and produce a workable implosion nuclear device based upon HEU [highly enriched uranium] as the fission fuel.” The IAEA has also expressed concerns that Iran may have conducted conventional high-explosive tests at its military facility at Parchin that could be used to develop a nuclear warhead.

There is no evidence, however, that Iran is currently working to design or construct such a warhead. Even if Iran made the decision, production of a warhead small enough, light enough, and reliable enough to mount on a ballistic missile is complicated. Iran would probably need at least a few years to accomplish this technological achievement.

Step 3: Marry the Warhead to an Effective Delivery System

If Iran built a nuclear warhead, it would need a way to deliver it. Tehran’s medium-range Shahab-3 has a range of up to 1,200 miles, long enough to strike anywhere in the Middle East, including Israel, and possibly southeastern Europe. These missiles are highly inaccurate, but they are theoretically capable of carrying a nuclear warhead if Iran is able to design one.

Iran’s Sajjil-2, another domestically produced medium-range ballistic missile, reportedly has a range of 1,375 miles when carrying a 1,650-pound warhead. Tehran is the only country to develop a missile with that range before a nuclear weapon. But the missile has only been tested once since 2009, which may mean it needs further fine-tuning before deployment. Iran also relies on foreign sources for a number of components for the Sajjil-2.

Iran is probably years away from developing a missile that could hit the United States. A 2012 Department of Defense report said Iran “may be technically capable” of flight testing an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) by 2015 if it receives foreign assistance. But in December 2012, a congressional report said Iran is unlikely to develop an ICBM in this timeframe, and many analysts estimate that Tehran would need until 2020.

Is the North Korean experience relevant?

The Clinton administration confronted a similar dilemma in 1993 on North Korea’s nuclear program. The intelligence community assessed that Pyongyang had one or two bombs’ worth of weapons-grade plutonium. But the intelligence community could not tell the president with a high degree of certainty if North Korea had actually built operational nuclear weapons.

The mere existence of a few bombs’ worth of weapons-grade plutonium seemed to have a powerful deterrent effect on the United States. Washington could not be sure where the material was stored, or if the North Koreans were close to producing a weapon.

The same concerns could apply to Iran if it developed the capability to produce weapons-grade uranium so quickly that it avoids detection even at declared facilities― or if it was able to enrich bomb-grade material at a secret facility. Then Iran might be able to hide the fissile material, making it more difficult for a military strike to destroy. All the other parts of the program, such as weapons design, preparing the uranium core, and fabrication and assembly of other key weapon components, could potentially be done in places dispersed across the country that are easier to conceal and more difficult to target.

Iran may be years away from being able to place a nuclear warhead on a reliable long-range missile. But many analysts are concerned that the game is up once Iran produces enough fissile material for a bomb.

Colin H. Kahl served as the deputy assistant secretary of defense for the Middle East from 2009 to 2011. He is currently an associate professor at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service and a senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security.

]]>via USIP

What is the state of Iran’s economy in 2013 compared to a year ago?

Iran’s economy enters 2013 significantly worse than a year ago, particularly with higher inflation and unemployment than at the beginning of 2012. The rial also plunged from around 11,000 to the dollar at [...]]]>

via USIP

What is the state of Iran’s economy in 2013 compared to a year ago?

Iran’s economy enters 2013 significantly worse than a year ago, particularly with higher inflation and unemployment than at the beginning of 2012. The rial also plunged from around 11,000 to the dollar at the beginning of 2012 down to between 22,500 and 31,000 at the beginning of 2013, depending on the type of transaction. The past year was probably the most tumultuous economically for Iran since 1994, when an external debt crisis triggered a serious inflationary shock and a recession.

At the outset of 2012, many Iranians expected another economic shock due to the growing array of sanctions on Tehran’s oil sales and financial transactions led by the United States and European Union. In 2013, many now expect the international economic cordon to be further tightened. The 2012 squeeze did not produce a hyperinflationary spiral, but annual overall inflation in 2012 was estimated to hit between 40 percent and 60 percent, according to Iran’s business media. Tehran was forced to limit foreign exchange transactions and the export of strategic goods in response to the effect of sanctions on Iran’s currency market.

Due to sanctions, Iran’s oil exports were also basically cut in half in 2012, from 2.3 million barrels a day at the beginning of 2012 down to around 1 million barrels a day at year’s end, according to the International Energy Agency. The accumulated impact of revenue declines is likely to produce two additional problems in 2013.

First, the national budget deficit is expected to increase to around 30 percent of the current budget (in the Persian year ending in March 2013), which means that President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad will be forced next year to cut spending, raise revenue, and prop up state banks with new cash injections. Iran’s parliament wants to put as much control over the government budget as it can, since many members of parliament contend that Ahmadinejad’s use of revenue is opaque at best.

Second, further changes in subsidies for basic commodities—which date back to hardships during the eight-year Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s—are on hold. Ahmadinejad introduced changes to this subsidy program over 2011-2012, including liberalization of some prices combined with monthly stipends for the entire Iranian population. But he only got through one round of subsidy cuts before Iran’s parliament halted further increases in fuel prices as well as higher stipends. Inflation had whittled away the benefits of both, although the idea is not dead.

Iranian economists are divided about subsidy reforms. Some think the subsidy cutbacks generated an inflationary shock at a time that the domestic economy—both the manufacturing and agricultural sectors—were unprepared for higher production and raw material costs that they then either had to absorb or pass along to consumers. So sanctions were not the only driver of inflation in 2012.

Other economists are more sanguine about the reforms, given the difficulties of enacting any economic policy changes in Iran. The ill-effects are temporary, they contend, and many other developing countries use stipends as part of their welfare programs. A diplomatic solution about Iran’s controversial nuclear program over the next year, they say, would lessen the pain and other subsidies could then be removed.

What is the debate within the government over what to do about the current economic situation?

The admission of economic woes by most of Iran’s political class has opened up space for debate over economic policy. Some officials, including the president, now argue that reducing Iran’s reliance on oil revenues, a byproduct of international sanctions, is a blessing in disguise. Private sector representatives in Iran’s Chamber of Commerce counter that they could manage the economy better than the state does. Both claims are seriously exaggerated, but the rival positions reflect the political impact of the deepening economic crisis in a presidential election year.

A viable solution may depend less on economic policy than on the outcome of Iran’s negotiations on its nuclear program, several Iranian officials have admitted publicly. Iranian officials are now gearing up for talks with the world’s major powers—the so-called P5+1—from the United States, Britain, China, France, Germany and Russia. Iranian negotiators want sanctions relief in exchange for any concessions limiting its nuclear program.

How much influence does the economic situation have on the presidential election due in June 2013?

The economy will clearly be one of the main issues in the election. Unlike many developing countries, however, Iran does not have a large external debt. It has a porous, open economy, which helps the country’s 79 million people deal with the negative effects of financial sanctions. So the situation is not yet dire. But people may vote for a candidate who they believe can actually get something done in the economic arena.

Many candidates will likely run against Ahmadinejad—notably his economic policies—even though he is not allowed to run again under a constitutional limit of two consecutive terms. Across the political spectrum, Ahmadinejad’s administration is now widely associated with failed policies and gross mismanagement. In 2012, most conservative media blasted the president and his staff for Iran’s growing economic woes.

Indeed, Iran’s economic policy debate has often served as a cover for political criticism since the 1979 revolution. The 2013 presidential election will almost certainly follow the same pattern, given growing economic woes and the linking of their alleviation with a resolution of the nuclear issue.

via the United States Institute of Peace

What are the primary reasons that the Iranian rial has lost half of its value against the U.S. dollar in just one year? Iran’s currency was valued at about 10,000 rials to the dollar in the summer of 2011. It plummeted to more than [...]]]>

via the United States Institute of Peace

What are the primary reasons that the Iranian rial has lost half of its value against the U.S. dollar in just one year? Iran’s currency was valued at about 10,000 rials to the dollar in the summer of 2011. It plummeted to more than 20,000 to the dollar in the summer of 2012.

What are the primary reasons that the Iranian rial has lost half of its value against the U.S. dollar in just one year? Iran’s currency was valued at about 10,000 rials to the dollar in the summer of 2011. It plummeted to more than 20,000 to the dollar in the summer of 2012.

Inflation in Iran’s economy has not been this bad since the end of the Iran-Iraq War or the economic crisis of the early 1990s, which also caused high inflation. The rial’s value began to slide rapidly at the beginning of 2012 after the United States announced new sanctions above and beyond the latest U.N. sanctions. The slide was due partly to the psychology of sanctions.

The government also went back to a tiered currency regime similar to what it had in the 1980s, during the Iraq-Iran War, and through the 1990s. Various types of imports and transactions had different exchange rates. Today, the official exchange rate is used for strategic imports such as food and medicine. That is another reason the price of rice did not go up a lot.

The price of chicken went up a lot, however, because Iran is not a socialist country. It cannot control the price of everything. Chicken farmers and wholesale buyers respond to market prices. The government capped the store price of chicken, but the price of chicken feed was going up because much of it is imported.

The state also stopped its phased subsidy reductions. It had planned to further cut longstanding subsidies for electricity, gasoline and utilities, but parliament told the president in the spring to continue the current level of subsidies. The president initially refused, but under parliamentary pressure has deferred any new price hikes. So U.S. and E.U. sanctions have forced the Islamic Republic to stop the subsidy reduction program that the International Monetary Fund and the Ahmadinejad government had been working on for years.

What roles have U.S. and international sanctions played in Iran’s currency drama? In July 2012, Parliamentary Speaker Ali Larijani said that only 20 percent of Iran’s economic problems were due to international sanctions. What is your assessment?

It is hard to put a number on what percentage U.S. and E.U. sanctions have on currency devaluation and inflation because both are produced by a combination of factors– what individuals do based on future uncertainty and the sometimes contradictory policies of the government.

The Central Bank has suggested that it may change the official exchange rate. What impact will that have? Will it solve the problem? Are there any side effects or dangers?

Some economists, including many in Iran, say the country needs a single rate. People make money playing the official and unofficial currency rates off each other. But the state does not have the luxury of unifying the rial’s value. So it is trying all sorts of stop-gap measures, which in the long term are harmful. They create opportunities for speculation. But the state, which is dealing in the short term, is in a double bind. Letting the official rate devalue would lead to such an inflationary burst that prices could go up even more.

“The problem,” they write, “is that democratic reform in Iran is a long-term proposition. As a [...]]]>

“The problem,” they write, “is that democratic reform in Iran is a long-term proposition. As a result, it cannot serve as the basis for an effective U.S.-Iran policy.”

“If the Obama White House were to rest its efforts to dissuade Iran from pursuing nuclear weapons on regime change, it would end up with an Iran policy as incoherent as those of the administrations that preceded it.”

Even though President Barack Obama seems to be trying very hard to distance himself from past polices — and avoiding the same results — Burmberg and Blechman write his policy is still muddled. (What are sanctions for, in the end? they ask, for example: “[W]e need to define that end far more clearly.”) The uncertain policy outcomes from the administration’s Iran policy creates room for more radical proposals like regime change:

As support for engagement wanes in Washington, calls for regime change are reverberating in the U.S. Congress and out national media. The idea that we can slay the Iranian nuclear dragon by destroying its autocratic heart will probably become a leitmotif of the House and quite possibly the Senate in 2011.

This seems to be the “forget negotiations” approach taken by a bipartisan group of six Senators who called on Obama to ensure ‘zero enrichment’ in any agreement. It’s almost definitely a deal-breaker for the current leadership of the Islamic Republic — or for even a reformed Islamic Republic.

Brumberg and Blechman explore many of these contradictions. Their piece should be informative for regime change hawks who constantly push the need for more aggressive U.S. support of domestic dissent in Iran (my emphasis):

Political reform will eventually come to Iran, but in manner far more prolonged and partial than that imagined by advocates of a full-scale democratic revolution. This kind of dramatic scenario may pluck a tour heart strings, but it has not been the animating vision of Iran’s reformists. The latter speak for a 25-million urban middle class of Iranians, many whom share one goal: to compel the state to stop forcing religious dogma on the population.

[...]

There is very little the U.S. can or should do to affect this prolonged dynamic [of the reform movement]. The more we embrace Iran’s democratic activists, the more we suffocate them. Iran’s reformists want the international community to stand up for their human rights; they do not want to be pawns of a U.S.-Iranian conflict. In a land where concerns about national sovereignty and religious identity cut across the regime-opposition divide, the quest for democracy will be discredited if it is seen as anything but homegrown.

There is one thing, however, that the U.S. can do promote political decompression in Iran, and that is to make détente with the Islamic Republic a top priority. Sustained U.S.-Iranian engagement would undercut the “threat” that ultra hardliners regularly invoke to legitimate their efforts to pummel or isolate their critics.

That’s been a huge problem of the discourse in the U.S. about Iran — one cannot make a priority both of the nuclear issue and the democracy issue. The same could be said of attacking Iran’s nuclear facilities.

The nuclear clock and the democratic clock are not in sync. Those in the United States who propose bombing Iran in order to both slow down the nuclear clock and speed up the democratic clock are being disingenuous. This is not to say that an accelerated democratic clock — leading to reform — won’t be more favorable to the West and may well slow down the nuclear clock itself. But the process of accelerating the democratic clock (a policy of regime change) holds the dangerous (and likely) possibility of backfiring and creating further insecurity and resentment. And insecurity and resentment would seem to be the top reasons behind the Iranian nuclear drive in the first place.

]]>These are the same allegations that Dennis Ross, Obama’s top National Security Council official for [...]]]>

These are the same allegations that Dennis Ross, Obama’s top National Security Council official for Iran policy, pushed back against in his talk yesterday at a U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP) event.

In the Leveretts’ piece, they cite a Huffington Post article by Reza Marashi, who just joined the National Iranian American Council (NIAC) as research director after four years in the State Department’s Office of Iranian Affairs:

It should now be clear that U.S. policy has never been a true engagement policy. By definition, engagement entails a long-term approach that abandons “sticks” and reassures both sides that their respective fears are unfounded. We realized early on that the administration was unlikely to adopt this approach. [...]

Moreover, as the leaked cables show, the highest levels of the Obama administration never believed that diplomacy could succeed. While this does not cheapen Obama’s Nowruz message and other groundbreaking facets of his initial outreach, it does raise three important questions: How can U.S. policymakers give maximum effort to make diplomacy succeed if they admittedly never believed their efforts could work? …And what are the chances that Iran will take diplomacy seriously now that it knows the U.S. never really did? The Obama administration presented a solid vision, but never truly pursued it.

This is pretty damning stuff from a guy who just left the Obama State Department. He was on the inside. And the Leveretts are feeling vindicated:

This, of course, provides additional powerful and public confirmation—from inside the Obama Administration—for our argument, in a New York Times Op Ed published in May 2009, that the Obama Administration’s disingenuous approach to dealing with Iran had already betrayed the early promise of President Obama’s initial rhetoric about engagement.

They mention that Ross was quite displeased with what they then had to say, and he let them know. The Leveretts note that Ross had Ray Takeyh, then his assistant at the State Department, push back against the notion that Obama’s “extended hand” to Iran was a checklist item for building international backing for more pressure on Iran, and possibly eventually military strikes. Takeyh called the idea “wrong and fraudulent.”

The Leveretts want to know what Takeyh thinks now:

]]>In light of the Wikileaks cables and Mr. Marashi’s public confirmation that the Obama Administration was, in fact, pursuing engagement to pave the way for more coercive options, including expanded sanctions, we ask Ray Takeyh: who was perpetrating a fraud with regard to the underlying intent of the Administration’s Iran policy?

Ross is an influential adviser to [...]]]>

Ross is an influential adviser to Obama on Iran issues, where he’s thought to be the prime architect of a policy aimed foremost at curbing Iran’s nuclear ambitions.

“The president has made it clear he is determined to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons,” said Ross. “The president has been very active in this area to mobilize the international community to the aims we want to pursue. Every meeting he’s had around the globe, Iran has featured very prominently.”

Ross gave a sweeping account of U.S. policy toward Iran since the start of the Obama administration, discussing motivations behind the both aspects of the White House’s “dual-track” engagement and pressure plan for Iran, noting the failures of the former and the successes of the latter.

As a Non-Proliferation Treaty signatory, Iran is entitled to nuclear power and repeatedly denies the widely held Western belief its program is aimed at producing weapons.

“We’re prepared to respect Iran’s rights, but rights come with responsibilities,” said Ross. “They have to restore the confidence of the international community in order to get those rights.”

Though Ross said there were many reasons for tensions, he believed the lack of a formal diplomatic relationship between Iran and the United States — “an absence of contacts between officials” – for the past thirty years has been a factor.

“Absence of contact had done nothing to prevent Iran from pursuing it’s nuclear program and it didn’t do anything to prevent Iran from increasing its reach in the region,” said Ross.

“If there’s one thing President Obama wanted to change it was that. He wanted to have an engagement program,” he continued. “He was prepared from the very beginning to reach out and did.”

Some analysts have suggested the United States never seriously tried engagement. Comments from diplomats, including those found in diplomatic cables released by WikiLeaks, reveal many believed negotiations were bound to fail even at the start of implementing the dual-track strategy.

“It is unlikely that the resources and dedication needed for success was given to a policy that the administration expected to fail,” National Iranian American Council (NIAC) president Trita Parsi observed.

“The only conclusion I can draw from this is that Obama was never sincere about his engagement strategy,” wrote Columbia professor and Iran expert Gary Sick. “It has yet to be tried.”

When asked directly about diplomatic engagement, Ross responded: “Everyone we have been dealing with knows quite clearly — they understand that we are quite serious and remian quite serious,” he said. “The president believed it was important to pursue diplomacy not as some kind of charade, but to change Iran’s behavior.”

He said that the robust sanctions passed in the UN Security Council last summer — which he hailed as a major success of the overall policy — are an indication of the U.S. seriousness.

“If we were seen as not being for real we would not have been able to do that,” he said.

On Tuesday, Iran announced it agreed to join the P5 + 1 (the five permanent members of the UN Security Council – China, France, Russia, the U.K, and the United States - and Germany) for negotiations next week in Geneva. Ross said he had hopes for serious talks, which he reportedly will attend.

Patrick Clawson of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy (WINEP), where Ross used to work, asked whether there will be talk of “pursuing other steps” at the P5 + 1 meetings — perhaps a nod at using the “military option” or addressing a choice the administration might face between that and pursuing the containment of an Iran with a nuclear weapons (or the capability to make them).

Either way, Ross deftly dodged the question: “I think you give plan A a chance before you go to plan B.”

“I think the most important thing is that we want these negotiations to get underway,” he added. “The expectation should not be that you go into the meeting and everything gets resolved.”

Addressing the aims of the Western negotiating group more broadly, Ross said, “The 5 +1 was created to deal with the nuclear issue. If you want to put other issues on the table, that’s fine. But there has to be a discussion of the nuclear issue.”

Last month, Iran’s president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad said of the upcoming talks that Iran’s nuclear rights were “not negotiable,” though many diplomats and experts thought the statement reflected Iran’s longstanding defense of its rights to nuclear power under the NPT.

“We will be watching the nuclear issue,” he continued. “[Obama is] not in talks for their own sake. If (the Iranians) are not serious, we’re going to see that.”

Ross dedicated much of his prepared comments to discussing Western successes in pressuring Iran, citing the UN and U.S. Congressional sanctions.

“There’s no doubt the impact of the sanctions is being felt,” he said, naming examples of many international companies that have reduced business with Iran, especially in the energy sector. “What it all adds up to is something pretty clear: The pressure on Iran is starting to grow.”

“Iran has the possibility to be (in the international community),” he said. “I hope it will take the chance because if not it will be squeezed more.”

]]>