With the 10th anniversary of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 coming up in October, the UN is under a lot of pressure to implement the resolution.

UNSCR 1325 calls on States to put an end to impunity and prosecute perpetrators of sexual and other violence on women and girls; increased participation of [...]]]>

With the 10th anniversary of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 coming up in October, the UN is under a lot of pressure to implement the resolution.

UNSCR 1325 calls on States to put an end to impunity and prosecute perpetrators of sexual and other violence on women and girls; increased participation of women in peace process; the protection and respect of women and girls post-conflict; and a framework for engendering peace negotiations, peacekeeping, planning of refugee camps and reconstruction.

The Security Council proposed penalties for perpetrators in the form of prosecution and targetted sanctions as well as strengthening the mandates of peacekeeping operations to prevent sexual gender based violence and to remind parties to conflict of their responsibility to protect women.

But very little progress has been made in protecting women and girls from rape in armed conflict. We have already celebrated many times over the fact that it UNSCR 1325 is a landmark resolution that recognises sexual gender based violence as a weapon of war. But beyond that, implementation has been so poor its not clear what we will be celebrating come October other than a statement of intent backed by more recent statements of intent in the form of resolutions 1888 and 1889 adopted in September 2009.

Resolution 1888 mandates peacekeeping missions to protect women and girls from sexual violence in armed conflict. Resolution 1889 reaffirms resolution 1325 and “condemns continuing sexual violence against women in conflict and post-conflict situations”. It urges Member States, United Nations bodies, donors and civil society to ensure that women’s protection and empowerment is taken into account during post-conflict needs assessment and planning, and factored into subsequent funding and programming.

Approximately 20 000 women were raped during the war in Bosnia and Hercegovina in the early 1990s and violations continue around the world with the most well-known case being the Democratic Republic of Congo where it is estimated that up to 500,000 women and children have been raped during the 14 year long war. Human Rights Watch and other rights and humanitarian organisations have reported sexual gender based violence in numerous other conflicts, including Afghanistan, Burundi, Chad, Colombia, Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, Peru, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Chechnya/Russian Federation and Uganda.

Efforts at remedying the situation in DRC by training police and government forces to protect women are limited by the fact that the government forces are amongst the worst perpetrators of sexual gender based violence. The Security Council is due to conduct a visit to the DRC from 14th to 21st May mainly to negotiate the gradual withdrawal of the the UN’s 20,000-strong peacekeeping force in that country. But it has already been criticised for its failure to include anything on women in its terms of reference for the visit. The TORS do, however, specifically mention children and “other affected civilian groups”.

The International Criminal Court Chief Prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo’s visit to Kenya to investigate the country’s post election violence will also need to be watched closely. In Kenya this week, Ocampo says he will speak with victims and government officials. Many of those victims are the women who were raped, beaten and had their homes burnt down. Ocampo’s mission should target them as a specific group and aim to deliver the justice that has so far evaded them and many other female victims of sexual gender based violence in conflict. As long as women affected by conflict continue to be lumped in the group “civilians” we are unlikely to ever give them the particular attention or action they need or address the fact that the rape of women in armed conflict is a very specific method of warfare meant to humiliate, terrorize, punish and dominate the enemy.

Meanwhile, the Ugandan rebel group, the Lords Resistance Army, continues to operate with impunity, extending their murderous campaign and abductions of women and children into DRC. Clearly the resolutions have had little impact on governments and armed groups and failed to act as a deterrent. It is also obvious that 1325′s call for the inclusion of women in peace processes is not being taken seriously. Women continue to be excluded from negotiating tables.

]]>MONTEVIDEO.- Cada vez que aparecen noticias sobre mujeres que se inmolan en sangrientos ataques terroristas, se me despierta la misma mezcla de sorpresa y horror.

Lo sentí también toda vez que supe de acciones similares cometidas por hombres, amargamente más comunes en las últimas décadas. Pero la sensación de [...]]]>

Diana Cariboni

Diana Cariboni

MONTEVIDEO.- Cada vez que aparecen noticias sobre mujeres que se inmolan en sangrientos ataques terroristas, se me despierta la misma mezcla de sorpresa y horror.

Lo sentí también toda vez que supe de acciones similares cometidas por hombres, amargamente más comunes en las últimas décadas. Pero la sensación de que las mujeres, aún las más desesperadas, estábamos a salvo de esa terrible forma de protesta, ¿es parte de la imagen sexista que tenemos del mundo?

El 29 de marzo, dos bombas en el metro de Moscú mataron a 40 personas y dejaron a 121 heridas.

Dos mujeres musulmanas hicieron estallar cargas explosivas que llevaban adheridas a sus cuerpos: Maryam Sharipova, una profesora universitaria de informática de 28 años, y Dzhanet Abdurakhmanova, una joven de 17 años presuntamente viuda de un militante separatista abatido por las fuerzas rusas.

La prensa insiste en que las dos eran viudas, aunque el padre de Sharipova dijo a la agencia AP que eso no tenía sentido, que su hija siempre había vivido en la casa paterna y que iba desde allí a la universidad, que era toda su vida.

Es que las versiones más difundidas, que llaman a estas atacantes “Viudas Negras” las describen como movidas por el deseo de vengar a sus familiares muertos o por la desesperación en que cayeron tras ser violadas o humilladas por las tropas rusas. Otro apunte frecuente es que son dirigidas por terroristas varones que las controlan a su entera voluntad.

La violencia en el Cáucaso Norte no es nueva. En esa región montañosa entre los mares Negro y Caspio, una cantidad de pueblos diversos luchan desde hace más de dos siglos contra la dominación rusa.

Pero los análisis coinciden en que las dos guerras de los años 90 entre Rusia y la pequeña e independentista Chechenia han deteriorado profundamente la situación de esa zona.

Derrotado en 1996, Moscú invadió Chechenia en 1999, abriendo una ola de atentados que se fueron mudando a territorio ruso y a objetivos civiles.

En Chechenia, las condiciones de vida se agravaron: creciente pobreza, violencia, violación masiva de los derechos humanos. ¿Eso es suficiente para que un grupo de personas se vuelque al terrorismo suicida? ¿Y por qué tanto mujeres como hombres han tomado esa opción en el Cáucaso?

“Ustedes están sufriendo un mal día, pero nosotros llevamos sufriendo 10 malos años”, le dijo una Viuda Negra chechena a un rehén ruso en el ataque al teatro Dubrovka de Moscú, en octubre de 2002.

Con esa cita, la investigadora Elizabeth Frombgen abre su artículo “Burkas, Babushkas, and Bombs: Toward an Understanding of the ‘Black Widow’ Suicide Bombers of Chechnya” (Burkas, babushkas y bombas: hacia una comprensión de las terroristas suicidas Viudas Negras).

El uso checheno de tácticas terroristas fue adoptado en 1995, cuando fuerzas de ese país tomaron rehenes en un hospital ruso. La primera vez que una mujer chechena se explotó en nombre de la causa nacionalista fue en junio de 2000. Ese fue también el primer acto terrorista de carácter suicida en el conflicto.

Desde entonces, más de 60 chechenas tomaron parte en ataques suicidas.

La información disponible sobre el perfil de las Viudas Negras tiene un denominador común: su juventud. Dentro del grupo cuya identidad es conocida, la mayoría tienen menos de 30 años. No todas eran religiosas, no todas habían perdido familiares en la guerra contra Rusia. Tampoco vivían en una pobreza abyecta ni hay datos de que hubieran sido violadas por uniformados rusos.

La lectura feminista que proponen algunos señala que la experiencia de las dos guerras afectó el rol de género de las mujeres de tal modo que pudo haber contribuido a una politización mediante el martirio terrorista.

Se trataría de una forma de participación política que aparece “debido a las experiencias femeninas en tiempos de guerra, como la ausencia de los hombres y la necesidad de ocupar nuevos roles que antes eran masculinos”, afirma Frombgen.

Pero esto sólo se manifiesta en “situaciones en las que hay una historia de terrorismo o ataques suicidas conducidos por hombres”, pues experimentar la guerra, las privaciones y las pérdidas no produce en forma automática “mujeres terroristas suicidas”, agrega.

La cultura y forma de vida de los pueblos autóctonos del Cáucaso son muy diferentes a las de Rusia, señala Nino Kemoklidze, candidata a un doctorado en el Centro de Estudios Rusos y Centroeuropeos de la Universidad de Birmingham en el artículo “Victimisation of Female Suicide Bombers: The Case of Chechnya (La victimización de las terroristas suicidas: el caso de Chechenia).

La célula de esa sociedad es el clan, “teipy”, una estructura cerrada y patriarcal. Su cultura e historia se construyeron en torno de los relatos de la “bravura” masculina de sus guerreros.

Los matrimonios están prohibidos dentro del teipy. En un “complejo sistema matrimonial inter tribal” los cuerpos femeninos son convertidos en “mercancía y objeto de intercambio político”.

En los 75 años de vigencia del régimen soviético esta estructura se debilitó, pero sus tradiciones y las normas islámicas consuetudinarias se siguen sintiendo hoy.

Una prueba de ello, dice Kemoklidze, es la tradición de “robar” una mujer para esposarla o aquella otra de la poligamia, ejercida en defensa del crecimiento demográfico.

Pese a la “equidad de género” proclamada por la Unión Soviética, incluso en ese período las mujeres fueron cosificadas. Como las regiones con alta natalidad eran recompensadas con mayores oportunidades de empleo y otros beneficios y subsidios, las chechenas debían parir muchos hijos. Servían, por tanto, como “objetos de ganancia económica”.

Incluso durante los 13 años de deportación ordenada por Stalin, la natalidad chechena permaneció elevada, quizás como una deliberada manifestación de nacionalismo ante al intento etnocida del estalinismo.

Nos dice Kemoklidze que tomemos en cuenta esta compleja estructura social en la que se mezclan tradiciones tribales, musulmanas y soviéticas, para entender el actual conflicto y el papel de las mujeres.

Más que nada, insiste, las mujeres eran percibidas como bienes de ganancia política o económica, con sus cuerpos permanentemente comprometidos en intercambios tribales, en el teipy, o dedicados a sostener la recompensada natalidad soviética.

¿Cómo es posible entonces que esta sociedad permitiera la formación de una identidad femenina terrorista y suicida? ¿Que las mujeres abandonaran su fin supremo, dar vida y nutrirla, para asumir la más masculina de las empresas, la guerra?

Pero es que desde que se hizo estallar la primera terrorista suicida moderna, en Líbano en 1985, todos los episodios siguientes se produjeron en sociedades machistas y patriarcales: Palestina, Turquía, Sri Lanka, Iraq y Chechenia.

Es que ni las mujeres son “esencialmente” pacifistas ni las condiciones sociales son favorables a otro tipo de participación, arguye Kemoklidze.

Los medios de comunicación han jugado un papel importante en describir a las suicidas como “víctimas desesperadas” del terrorismo checheno, “drogadas” o “con el cerebro lavado”. O bien como víctimas de violaciones sexuales en manos de las tropas rusas, con esposos o hermanos brutalmente torturados. De pronto se convierten en personajes que casi despiertan simpatía.

La autora no niega que algunas de esas razones movilicen a los chechenos a la violencia, sean hombres o mujeres. Pero, advierte, el mundo occidental, que acusa al Islam de “una estricta demarcación social”, termina “atrapado en una visión con cristales similares”.

La agresión sigue siendo territorio masculino, mientras las “mujeres violentas sufren desequilibrios mentales o están poseídas por un mal inimaginable”.

Este mito nos impide entender la violencia y sus complejidades. En casi todos los actos terroristas chechenos ha habido mujeres. Fueron muchas las que detonaron bombas en estaciones de metro, autobuses y aviones, matando a decenas o cientos de personas. “¿Qué son esas mujeres, sino actoras de esta guerra brutal?”, se pregunta.

Las Viudas Negras no luchan sólo por venganza o por una tragedia personal. Y al hacerlo, quizás indirectamente o sin intención, “desafían las fronteras de los géneros… transgreden la profunda división entre lo público y lo privado”, afirman Nickie Charles y Helen Hintjens.

No se trata de justificar los crímenes, las muertes, las explosiones. La nueva forma en que algunas mujeres se vinculan con la violencia “no puede ser indicador de progreso hacia la equidad de género”, advierte Cindy Ness.

Si hay algo que la violencia no proporciona es justicia y equidad.

]]>

With the Beijing +15 review coming up next week at the Commission on the Status of Women, it seems an appropriate time to have a look at where we are globally in terms of gender equality and women’s empowerment in line with the 12 Critical Areas under the Beijing Platform for Action.

Women live longer than men but these extra years are not always healthy, says WHO. Credit: WHO/UNAIDS/K.Hesse

With the Beijing +15 review coming up next week at the Commission on the Status of Women, it seems an appropriate time to have a look at where we are globally in terms of gender equality and women’s empowerment in line with the 12 Critical Areas under the Beijing Platform for Action.

Women and poverty

Vulnerable employment has decreased globally by three percentage points since 1997, says UNIFEM in its 2008 annual Progress of the World’s Women report. But about 1.5 billion people are still in this category and the share is larger for women at 51.7 per cent. While global progress is important, national-level data indicate that women are still more likely than men to be poor and at risk of hunger because of the systematic discrimination they face in access to education, healthcare and control of assets. For example, in Malawi, there are three poor women for every poor man, and this proportion is increasing.

Education and training of women

According to findings from the twelve African countries where the UN Economic Commission for Africa’s African Gender and Development Index (AGDI) was piloted, at primary level, South Africa and Tunisia show higher female enrollment compared to males. Parity in primary enrollment also appears imminent in seven countries (Cameroon, Egypt, Ghana, Madagascar, Mozambique, United Republic of Tanzania and Uganda), while for Benin, Burkina Faso and Ethiopia achievement of the MDG 2 target of ensuring that girls and boys will be able to complete a full course of primary schooling by 2015 is likely to take longer.

Women and health

HIV, pregnancy-related conditions and tuberculosis continue to be major killers of women aged 15 to 45 globally, the World Health Organisation says in its November 2009 report, ‘Women and health: today’s evidence tomorrow’s agenda’. The report also notes that lack of access to education, decision-making positions and income may limit women’s ability to protect their own health and that of their families. Though major differences exist in women’s health across regions, countries and socio-economic class, women and girls face similar challenges, in particular discrimination, violence and poverty, which increase their risk of ill health.

Violence against women and Women in Conflict

According to the U.N. Population Fund (UNFPA), more than 8,000 women were raped by warring factions in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) last year, while over three million young girls are at risk of undergoing female genital mutilation worldwide. The scourge of gender based violence is worsened by the impunity enjoyed by perpetrators.

The U.N. Development Programme (UNDP) estimates that out of nearly 1,000 sexual abuse and over 1,500 domestic violence cases reported in Sierra Leone last year, there wasn’t a single conviction.

Women in power and decision-making

Women currently comprise an average of 18.7 percent of both the lower and upper houses of parliament globally, according to the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU). Rwanda, with 56.3 percent, heads the list, followed by Sweden (46.4%), South Africa (44.5%), Cuba (43.2%) and Iceland (42.9%). But according to UNIFEM, even at the current rate of increase of less than one percent from 1975 to 1995, it will take developing countries nearly 50 years to achieve parity unless countries continue establishing quotas or other temporary positive action measures. You can check IPU to see where your country stands. http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/classif.htm

Institutional mechanisms for the advancement of women

Although most countries have established national machineries to deal with the Beijing Platform for Action commitments, inadequate financial and human resources, lack of clear focus; uncertainties in co-ordination and limited research have rendered the vast majority of these institutions ineffective.

Human rights of women

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) is the international human rights treaty for women. Adopted by the U.N. General Assembly on 18th December 1979, it recently marked its 30th anniversary and has been ratified by 186 countries. Among the AGDI pilot countries, all 12 countries have ratified CEDAW. However, three (Egypt, Ethiopia and Tunisia) have maintained reservations to date. Particularly in the cases of Egypt and Tunisia, these reservations relate to “CEDAW core areas”: Articles 2 and 16, which deal with enforcement of non-discrimination and equality in marriage and family life.

Though many countries have integrated non-discriminatory clauses into their constitutions and put in place gender sensitive legislation on marriage, family and property relations, implementation tends to be limited by the continued operation of customary law and limited capacity of enforcement agencies.

Women and the media

According to the 2009 Gender Links study, ‘Glass Ceilings: Women and Men in Southern African Media‘, men remain the predominant employees in media houses in the 14 Southern African Development Community member countries, with men constituting 59 percent of employees. In top management, women comprise only 23 percent of top managers.

On the positive side, where reporting is concerned, there is gender parity (50/50) in the coverage of sports in Botswana, while women constitute 40% of sports reporters in South Africa. Women (83%) also dominate in the coverage of economics/business/finance in South Africa and in Namibia (71%).

Women and the environment

According to the U.N. Population Fund and the Women Environment and Development Organisation (WEDO), poor and disadvantaged women are disproportionately affected by natural disasters and are overrepresented in death tolls. For example:

• Women and children are 14 times more likely to die than men during natural disasters;

• More than 70 per cent of the dead from the 2004 Asian tsunami were women; and

• Hurricane Katrina, which struck New Orleans, USA, in 2005, predominantly affected African American women—already the region’s poorest, most marginalized community.

The girl child

Female genital mutilation (FGM) remains one of the commonest harmful traditional practices in many parts of the world, says the UN. It is practiced in more than half of the countries in Africa, with the prevalence ranging from 98 percent in Somalia to five percent in the Democratic Republic of Congo. At least 100 million women and girls in Africa have been victims of FGM.

Girls also continue to be affected by son preference, early marriage and pregnancy, trafficking, violence in conflict and post-conflict situations and other forms of gender based violence.

]]>Why today? Because it’s the last of the 16 Days against Violence against Women, arguably the best known global campaign of the women’s movement, and also Human Rights Day.

Today, Sahrawi activist Aminatou Haidar starts her fourth week of [...]]]>

What's in the news on Human Rights Day?

Why today? Because it’s the last of the 16 Days against Violence against Women, arguably the best known global campaign of the women’s movement, and also Human Rights Day.

Today, Sahrawi activist Aminatou Haidar starts her fourth week of hunger strike at Lanzarote airport in the Canary Islands. She is so weak she has to be transported to court by wheelchair or stretcher. Last week, the head of UNHCR called on Spain and Morocco to resolve her issue on humanitarian grounds.

The award-winning Haidar is known as the Sahrawi Gandhi for her non-violent protests for the independence of her desert country, the Western Sahara, ruled by Morocco since 1975.

In November, the Moroccan government unlawfully withdrew her passport and deported her when Haidar returned from receiving the prestigious Civil Courage Prize in New York. In 2008 she received the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights award.

On the other side of the world, in the Philippines, on 23 November, the eve of 16 Days, 22 women were massacred along with 35 men. The women were raped, sexually mutilated and shot in their private parts. The mass murder was instigated by a local politician-warlord and carried out by his militia. Among the victims were the wife and sister of a rival political candidate and two women lawyers who worked for him.

Believing that the Muslim tradition of respecting women would protect them from clan violence, the group was going to file papers for the candidate, along with a group of journalists. Among the 57 killed were 30 thirty media people, journalists, technicians and drivers. This is the largest single killing of journalists in history.

Earlier in November, Cuban blogger Yoani Sanchez, along with two less well-known bloggers, a woman and a man, were detained and beaten up by authorities in Havana. They were on their way to a peaceful march.

Is this cause for despair? No. These examples of violence unleashed against women in politics and media only reaffirms our commitment to denounce these crimes and seek justice.

The media now has a better tool to do this job. On 25 November, IPS presented its new handbook on reporting on women and violence. User-friendly, with an agile layout, it covers a wide spectrum of issues, from cyberstalking to trafficking, with story examples, discussion points, fact checks and additional resources. Download it here.

Do it now! No time to lose!

Email your support for Aminatou here or at: todosconaminatou@gmail.com

And do whatever you can do to end violence against women and protect human rights defenders wherever you are.

]]>

Marie Mendene is an extraordinary activist from Cameroon and one of the first African women to say publicly that she lives with HIV, in the 1990s, when AIDS was a disease of shame and blame.

This is one of my favourite photos about AIDS [...]]]>

By M. Sayagues

Marie Mendene is an extraordinary activist from Cameroon and one of the first African women to say publicly that she lives with HIV, in the 1990s, when AIDS was a disease of shame and blame.

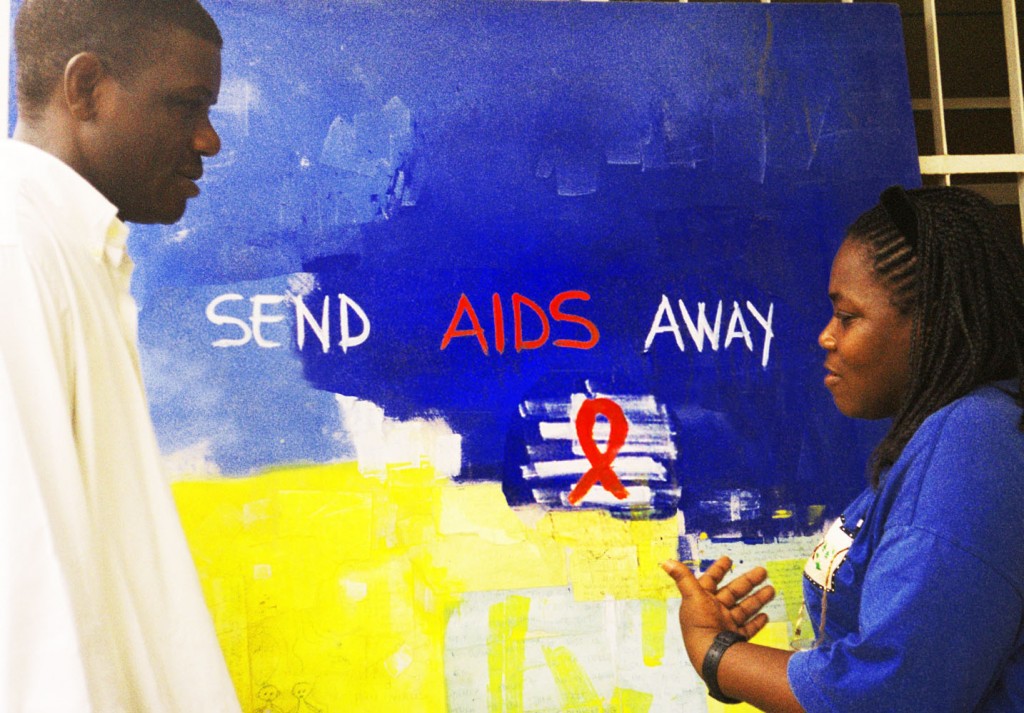

This is one of my favourite photos about AIDS in Africa. I took it at Sunshine, her NGO in Douala, in 2003, before antiretroviral treatment became widely available. Only a few Cameroonians in cities could get the life-saving pills.

The day I took the photo, Marie had queued for seven hours and received only half of her monthly ARV pills. She was understandably upset about the poor logistics and delivery of medicines. AIDS magnified all the inadequacies of health systems.

That was then. Today, nearly three million people in Africa are on ARV treatment. This seemed like a dream then, but activists were campaigning hard to make it come true.

Marie had a clear vision of activism. “We should go beyond the begging bowl and the appeal to compassion, beyond the stage of being used to do prevention and awareness, and become part of real-decision making around AIDS,” she told me.

Marie is to the right in the pic, with a fellow activist.

]]>What happens when the relatives of the murdered confront their murderers? What happens if they have to live with the murderers?

This is the theme of “My neighbour, my killer”, a film about Rwanda’s extraordinary attempt at reconciliation. This documentary by Anne Aghion, which premiered in New York two weeks ago at the [...]]]>

Remembering in Rwanda. Courtesy Anne Aghion

What happens when the relatives of the murdered confront their murderers? What happens if they have to live with the murderers?

This is the theme of “My neighbour, my killer”, a film about Rwanda’s extraordinary attempt at reconciliation. This documentary by Anne Aghion, which premiered in New York two weeks ago at the Human Rights Watch film festival, follows a gacaca or community court during five years.

Rwanda has set up some 12, 000 gacaca where killers face the relatives of those they killed during the genocide in 1994. (Read an interview with Aghion here).

A world and an age away, the same questions emerge in “Katyn”, the magnificent, sombre and sober epic movie made in 2008 by Polish director Andrzej Wajda about the Soviet massacre of 20,000 Poles during World War 2. During the ensuing five decades of occupation of Poland, the Soviets falsified history in a web of institutional lies and blamed the Nazis for the mass murders.

Both films are meditations on memory and history and their distortions, on loss, cruelty and forgiving, on imperfect justice, atonement and healing.

Women are central to both films – they are witness to horror and keepers of memory.

Think of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo haunting the Argentine junta with the photographs of their disappeared sons and daughters in the 1980s.

Gendering truth, gendering abuse

At truth and reconciliation commissions across the world, the bulk of testimonies by women dwell more on their loved ones and less on their own sufferings.

This is changing, as truth commissions become more gender-aware and seek gendered narratives. Earlier commissions, such as Argentina and Chile, were gender-neutral (some say gender-blind). South Africa was gender-neutral in its mandate but had special hearings for women. Peru’ commission had a gender unit. Later ones, like Haiti, Sierra Leone and Timor Leste, have looked specifically at sexual violence.

And more: the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia have ruled that mass rape, sexual assault, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced abortion and forced pregnancy may be crimes against humanity, torture and genocide.

A third film that I saw recently is “Persepolis”, Marjane Satrapi’s wildly popular graphic novel turned animated movie, about her life growing up as a girl who likes Michael Jackson and punk music under the ayatollahs in Iran in the 1980s.

Protesting in Tehran. Photo: M. Avazbeigi

Its charming animation overlays a dreadful national and family history of imprisonment, torture, disappearances, failed revolutions, dashed political hopes, war and Shariah.

The movie conveys a poignant description of another form of gender abuse: the repression of women’s freedom to dress, move about, work, study, divorce, inherit, love and have fun.

Repressed, but not cowed into submission: as I write, on the streets across Iran, women are protesting, being beaten up, arrested and killed, challenging theocracy, demanding their rights.

(Read about women protesters in Iran and about dismantling a culture of impunity in Guatemala, Peru and Democratic Republic of Congo)

]]>