by Robert E. Hunter

Publication this month of Vali Nasr’s The Dispensable Nation: American Foreign Policy in Retreat, could not have been better timed. The US and the NATO allies are in the process of disengaging from Afghanistan — however they choose to describe the process — without first [...]]]>

by Robert E. Hunter

Publication this month of Vali Nasr’s The Dispensable Nation: American Foreign Policy in Retreat, could not have been better timed. The US and the NATO allies are in the process of disengaging from Afghanistan — however they choose to describe the process — without first developing clarity about what comes next and how to understand or secure the West’s continuing interests there or in the region. The Syrian civil war continues, seemingly without end and without success so far in the US government to develop a coherent policy or, apparently, efforts to fit that conflagration within developments in the region as a whole. President Obama has just visited the Near East, but there is as yet no promise that serious negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians will begin anytime soon. The standoff with Iran and its nuclear program continues. And there are widespread doubts about the staying-power of US commitments and policies throughout the Middle East and Southwest Asia. For some observers, including Nasr, all this leads to serious questioning about the overall conduct of American foreign policy, summarized in his judgment: “retreat.”

The author, now Dean of the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University in Washington, has had a special vantage point. From January 2009 until 2011 Nasr was special advisor to Ambassador Richard Holbrooke (who died in December 2010), who was the President’s (and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s) Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan — shortened to the more digestible “AfPak.” It is not too much to say that Dr. Nasr’s brief but intense experience in the US government at a high level was both disappointing and disillusioning — and he was not alone. His principal conclusion, at least as inferred by this reviewer, is that the Obama White House failed to take seriously the diplomatic opportunities that were afforded the US, not just toward AfPak, but in the region overall; that it continued to tolerate an excessive militarization of US policies begun by earlier administrations at the expense of a more integrated approach where diplomatic instruments could play their proper role; that the president himself was long on language — eloquently so — but short on action and in the process failed to come to grips with a number of regional developments; that the best efforts by the State Department, including by Secretary Clinton, to intervene in critical policy-making were too often either rebuffed or ignored; and that the US has failed in its essential leadership role. Indeed, the title of Nasr’s book, Dispensable Nation, is a play on a term first coined by Secretary of State Madeleine Albright to the effect that the US in the post-Cold War world remains the “indispensable nation.”

(Nasr also does valuable service by eviscerating the case made for sanctions and yet more sanctions against Iran in order to get it to do what we want on its nuclear program, as well as on other matters, including the sub-rosa effort undertaken by the US, Israel and Saudi Arabia to eliminate Iran completely as a competitor for influence in the Middle East. However, the author’s insight comes at a price. His need to paint a dark picture of Iranian ambitions for the bomb and for regional hegemony, coupled with his shredding of the case for sanctions, leaves one wondering whether there is any alternative to war.

On China Nasr provides valuable service by alerting us to the fact that it — like often neglected countries such as Russia — also has major ambitions in Southwest Asia and parts of the Middle East. But he over-interprets available evidence, draws too many connections by linking murky data and too readily assumes that there will inevitably be contention, if not open confrontation, between the US and China.)

What Nasr says about the way in which the White House controlled foreign policy in Obama’s first term and made it highly subservient to domestic politics, at times thereby neglecting critical foreign interests, is a damning indictment – even if only partly true, and at this point in history, no outsider can judge. Nasr is not the only one to argue a similar thesis, but it is the first to be made, as far as this reviewer is aware, by someone as intimately involved in at least one major element of US policy implementation. This helps to explain why a book that has not yet hit bookstores has gained so much attention, apart from the usual Washington parlor game of welcoming “kiss and tell,” merged with a desire to see whoever the sitting president is stub his toe or worse. On all of this, Dispensable Nation delivers. It is a compelling read, even though it occasionally gets bogged down in detailed analyses of issues which most people will know little about. And while Nasr cannot be counted as a member of the new cottage industry of “declinists,” he does warn that, without a radical rethinking about the making and carrying out of US foreign policy, this nation can do itself and its role in the world serious injury, not least to its reputation and to the willingness of others to rely on it.

So far, so good. But there are some other facets of this book, which, while not reducing the author’s valuable insights listed above, at least present a somewhat different perspective. One might be a quibble on the part of an “old school” approach to government service: that someone who voluntarily “takes the King’s shilling” implicitly assumes a burden of not telling tales out of school, at least not until all the senior players have left the stage. Of course, breaking with that unwritten practice makes for a juicier read, but also leads one to ponder.

A more serious question is raised by the apparent assumption running throughout the book that, if a different approach had been taken to X or Y — in particular a greater reliance on diplomacy and giving free rein to diplomatic approaches advanced by the Special Representative, Ambassador Holbrooke (who appears in Dispensable Nation to have been the lead character of an “inside the Beltway” morality play), then very different, positive things would have resulted. This would be a reach in regard to any region of the world. With regard to the Middle East and its long history of complexities and imponderables — more even than what Winston Churchill said of Soviet foreign policy, “a puzzle inside a riddle wrapped in an enigma” — one should be chary of drawing hard-and-fast conclusions about the impact of different policies that might have been pursued. Thus, it is difficult to believe that, without other major factors changing, US leadership would on its own somehow have transformed Arab-Israeli peacemaking; that a different US approach to Egypt and other Arab countries would have produced a better course for the Arab Spring; that earlier intervention (but exactly what?) would have ended the slaughter in Syria; and that the negotiating strategy advocated by Ambassador Holbrooke would have brought the Afghanistan war to a successful conclusion (without taking us all back to Square One with the Taliban again in full control) and with US-Pakistan relations on better footing and the region stabilized.

To summarize, in addition to the highly relevant and well-argued analysis of the Obama administration’s shortcomings, many of the author’s suggestions for alternative approaches are more wishful thinking than the product of deep knowledge about the region and seasoned judgment concerning the very real limits of power, however “powerful” the actor. Perhaps that is an unfair conclusion, given that Nasr’s role in AfPak was the his first venture into government, but that gives greater weight to the admonition about being careful with drawing needlelike conclusions and making sweeping predictions about alternative strategies and their putative outcomes.

It might also have been useful if Dr. Nasr had drawn upon his experience to discuss whether the practice of using special representatives instead of common and garden-variety diplomacy is a good or bad thing. In some cases, appointing a US special negotiator has had positive effects – like in Arab-Israeli peacemaking, where a special negotiator can relieve a Secretary of State from having to deal virtually full-time with demanding and quarrelsome partners; or lengthy arms control negotiations, where having at the table experts from outside the Foreign Service can be essential, as the Obama administration, in this reviewer’s judgment, has ably and effectively done. But other than these exceptional circumstances, substituting a special representative for the regular practices and processes of the US government is just asking for trouble. This was certainly true in regard to the plethora of special representatives appointed during the first Obama administration, thereby short-circuiting the regular workings of government so much so that the expertise and experience needed to formulate and implement effective policies were at times missing or sidelined. Certainly, the balancing of contending (and legitimate) points of view from different elements of the bureaucracy (e.g., state, defense, CIA, NSC staff) risked being lost, to the detriment of coherent policy that could be effectively integrated for the longer-term with other related US concerns abroad beyond the purview of the special representatives.

Add to this the appointment of a special representative for AfPak who had achieved almost superstar status, with personal ambitions to match and a well-deserved sobriquet of “bulldozer,” and it would be surprising if all had gone smoothly within the US government — not least because Amb. Holbrooke, the hero of Dispensable Nation, had no experience in the region and no prior knowledge of the issues or the local political cultures. Indeed, it did not go smoothly, predictably so given Amb. Holbrooke’s career-long disdain for anyone who got in his way (along with his methods for eliminating competitors for either position or limelight), his lack of capacity for genuine strategic thinking as opposed to short-term tactical fixes, and his most undiplomatic approach to friend and foe. In fact, since his highly publicized spat with Afghan President Hamid Karzai who, like it or not, is someone the US has had to deal with, Holbrooke’s role as an interlocutor ceased to be useful to the United States.

In sum, Nasr has not only given us a good read but also a former insider’s judgments about what happens when a US administration does not place a high enough priority on getting right the US role in the world; does not assess adequately what it truly needs to do (instead of issuing slogans like “pivot to Asia” that confuse allies and imply reduced US interest in the Middle East and Southwest Asia at the very time when peril to American interests there is increasing); that inserts domestic political judgments at the start of the process instead of after due consideration of foreign policy choices; that permits a continuing imbalance between military and non-military instruments of power and influence; and that does not yet adequately “think strategically” about the future two decades after the end of the Cold War made such strategic thinking imperative.

Whether Dr. Nasr is right on both his analysis and his prescriptions will now be hotly debated. In any case, Dispensable Nation has emerged as valuable evidence supporting one important point of view.

]]>by Henry Precht

Two US service members were killed and at least eight others injured Monday in an insider attack at a Special Forces site in Afghanistan. The Taliban asserted responsibility. This incident would seem to nullify President Hamid Karzai’s earlier charge that US and Taliban forces were colluding [...]]]>

by Henry Precht

Two US service members were killed and at least eight others injured Monday in an insider attack at a Special Forces site in Afghanistan. The Taliban asserted responsibility. This incident would seem to nullify President Hamid Karzai’s earlier charge that US and Taliban forces were colluding to bring down his government.

The incident — and Karzai’s outburst — certainly did nothing to alter President Barak Obama’s determination to close out our war against al Qaeda and their former hosts and rulers of Afghanistan, the Taliban. By December 2014, the White House has said, our combat operations will have withdrawn and the Afghan government will be more or less on its own. How is this end game to be managed? Perhaps speaking for himself, the top general for the region, Gen. James N. Mattis, told Congress last week that 20,000 troops should remain after 2014.

I asked two experts separately for their views. One served in Afghanistan in the 1960s as a political counselor and the other returned last year from a lengthy assignment that included a period as deputy ambassador.

Here’s what the old timer had to say:

By December 2014 we will have done about all that can be accomplished with regard to (1) al Qaeda (the reason we went into Afghanistan in 2001) and (2) the Taliban insurgency — without the full support of Pakistan. That country’s tribal belt along the Afghan border provides rest and training for both of our adversaries. Our forces, particularly the Marines in Kandahar Province, have badly injured the Taliban and drone attacks have decimated al Qaeda’s leadership which has largely refocused its activities in the Yemen and East and North Africa. The remaining task for our forces is strictly training of the Afghan army and other security forces. Before that can be a reality, however, the Afghan government will have to give American troops (perhaps up to 10,000) legal immunity under a Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) that the Loya Jirga (a national assembly) must pass. Inevitably, our presence has started to rankle many Afghans, some of whom view us as another occupation force like so many in their history. The Loya Jirga’s debate and vote will be a fateful decision on how we are now perceived by the Afghan people, how confident they are that they alone can successfully contend with the Taliban and handle all the conflicts and rivalries in what is still a very traditional and tribal society.

Turning to the new boy:

The number of our troops who remain should be governed by their missions (and by the SOFA we manage to negotiate with the Afghan government). I see two missions for the post-2014 US military presence: training the Afghan National Army and counterterrorism (going after al Qaeda remnants.)

As the most recent casualty figures reflect, the Afghan Army has taken over the great bulk of the fighting. But they will still need our training, mentoring and assistance in several “high end,” “enabler” areas as the US military likes to call them: medical response, search and rescue, intelligence and its exploitation, logistics, high end equipment maintenance, their fledgling air force and — most important — civilian casualty avoidance. (We have learned a lot in this area.) The Brits, Italians, Germans, Lithuanians and others all have niche expertise to apply to this project, but we have to lead and coordinate with the Afghan government.

Numbers? I’m not a military expert, but would guess that somewhere between 10 and 20,000 will be necessary. They should be based in a few regional centers around the country for economies of effort and Afghan public perceptions.

Civilian complementarity: It’s absolutely essential that we NOT cut back to the bone our USG civilian programs in development, good governance and justice and exchanges as our military presence substantially declines. Even with all the nation’s corruption and poor governance, much social and economic progress, as well as human rights advances especially for Afghan women, has been made these past 12 years. As we have learned in other trouble spots: “there’s no security without development and no development without security.” A leaner but still robust US civilian presence and programs will do much to reassure very anxious Afghans, some of whom are still fence-sitters. Afghans have long memories, and while Afghanistan has changed much since the Soviet withdrawal, some draw parallels. Perceptions matter.

What about Pakistan? — insurgent safe haven, role in the emerging peace process involving the Taliban, the Talibanization of some parts of its territory, nuclear weapons, relationship with India — all matter tremendously, especially for Afghan prospects, but that’s a subject for another day.

There you have it, facts and informed opinions to chew on as the debate over our role in Afghanistan rumbles and rattles on in Washington. Left out of these Foreign Service judgments are any discussion about what American public opinion will tolerate and, perhaps most important, what price for continued engagement our budget will support.

Photo: President Barack Obama and President Hamid Karzai of Afghanistan participate in a bilateral meeting in the Oval Office, Jan. 11, 2013. Dr. Rangin Dadfar Spanta, Afghan National Security Advisor, left, and National Security Advisor Tom Donilon, attend. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

]]>Two interesting — but little-noted — developments on the Hagel front over the last couple of days.

First, Paul Wolfowitz endorsed former Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Michele Flournoy to replace Leon Panetta based on her understanding of and advocacy for the importance of training Afghan forces to prepare [...]]]>

Two interesting — but little-noted — developments on the Hagel front over the last couple of days.

First, Paul Wolfowitz endorsed former Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Michele Flournoy to replace Leon Panetta based on her understanding of and advocacy for the importance of training Afghan forces to prepare them to fight on their own against the Taliban. Whether this constitutes a kiss of death for Flournoy’s candidacy, I have no idea. But I imagine that, given his record on both Iraq and Afghanistan, Wolfowitz’s endorsement is one of the last she would want to have at this moment. (Remember: it was Wolfowitz who denounced Gen. Eric Shinseki’s estimate that it would take hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops to pacify the country as “wildly off the mark.”) Worse for Flournoy, Wolfowitz concludes that it is a “vital” U.S. interest to prevent the Taliban from returning to power, suggesting that Flournoy at the Pentagon would somehow ensure that this would not happen (despite the fact that the Obama administration has repeatedly indicated it could accept the return of the Taliban in some kind of power-sharing agreement based on certain conditions, notably its definitive break with Al Qaeda). According to Wolfowitz:

[I]t’s also vital for the US to prevent the Taliban from returning to power in Afghanistan, so we have a huge stake in the Afghan Security Forces.

Flournoy not only grasped the centrality of that strategic point, but she pursued it skillfully and without seeking credit for what she did. As far as I know, none of this has been reported before. But it deserves to be.

It leads me to think that Flournoy might be the best possible candidate for the top Pentagon job during the coming difficult years in Afghanistan. She does not seem to be someone who would comfortably let that war be lost.”

Now, to conclude that Flournoy would or could prevent that outcome, one would have to assume that U.S. troops would remain heavily engaged there after the 2014 withdrawal date, more engaged than I would imagine Obama would prefer. Plus, as in Iraq, if the Kabul government does not agree to a provide legal immunity to U.S. soldiers there as part of a future Status of Forces Agreement, what, if anything, can Flournoy do about that?

The second development was the announcement, in an “exclusive” to the Washington Post’s resident hard-line neo-con blogger, Jennifer Rubin, that the Senate Minority Whip, Texas Sen. John Cornyn, opposed Chuck Hagel’s nomination as Defense Secretary. There’s a lot of nonsense in Cornyn’s statement, but my eyes — after Ali pointed it out to me — focused on the part that had played a sort of catalytic role. According to Rubin, Cornyn asserted that Hagel “said he wouldn’t support all options being on the table” during a 2010 Atlantic Council briefing by the Council’s Iran task force. Rubin helpfully linked to the transcript of that briefing.

In fact, however, Hagel did not say he wouldn’t support “all options being on the table” in response to my question about whether it was helpful — to promoting human rights in Iran or improving prospects for a negotiated agreement on its nuclear program — for U.S. officials to constantly remind the Iranians that “all options are on the table.” This was his reply:

I’m not so sure it is necessary to continue to say all options are on the table. I believe that the leadership in Iran, regardless of the five power centers that you’re referring to – whether it’s the ayatollah or the president or the Republican Guard, the commissions – have some pretty clear understanding of the reality of this issue and where we are.

I think the point that your question really brings out – which is a very good one. If you were going to threaten on any kind of consistent basis, whether it’s from leadership or the Congress or the administration or anyone who generally speaks for this country in anyway, than [sic] you better be prepared to follow through with that.

Now, Stuart [Eizenstat, Hagel's co-chair on the task force] noted putting 100,000 troops in Iran – I mean, just as a number as far as if to play this thing out. The fact is, I would guess that we would all – I would be the one to start the questioning – would ask where you’re going to get 100,000 troops. (Laughter.) So your point is a very good one, I think.

I don’t think there’s anybody in Iran that does not question the seriousness of America, our allies or Israel on this for all the reasons we made very clear. And I do think there does become a time when you start to minimize the legitimacy of a threat. When you threaten people or you threaten sovereign nations, you better be very careful and you better understand, again, consequences because you may be required to employ that threat and activate that threat in some way.

So I don’t mind people always, as we have laid out, and I think every president and every administration, anybody of any consequence who’s talked about this can say – does say. But I think it’s implied that the military threat is always there. [Emphasis added.]

So Hagel never said that he doesn’t believe “all options are on the table.” He said that you have to be careful about not repeatedly making such a threat, because the Iranian leadership understands it already, and the more you repeat it, the less credibility it has. This is Hagel’s version of TR’s ”speak softly and carry a big stick.”

What we have here is yet another example of the neo-con propaganda machine/echo chamber. Someone gives a credulous or complicit staffer in Cornyn’s office a list of talking points, at least one of which is demonstrably false; the staffer tells Rubin or someone else close to her that Cornyn is willing to publicly attack Hagel based on these talking points; Rubin calls Cornyn and gets him to spout them (including at least one that is demonstrably false) on the record. (Several others are taken completely out of context). Then she claims that the Minority Whip is now firmly opposed to Hagel’s nomination (based on information that is demonstrably false), quoting him extensively, and thus providing additional evidence and momentum for her previous suggestion (made the day before) that Hagel is “toast.“ And then she has the audacity/chutzpah/carelessness to link to a briefing that she wants her readers to believe proves Cornyn’s claim but that in fact shows that his claim is false. Is this deliberate or negligent on her part? Did she read the transcript before she linked to it? Or did she simply link to it because someone had given her the same or a similar version of the talking points, and she failed to investigate their reliability? I don’t think any of that is important to her; her main goal is to prevent Hagel’s nomination. (For more on Rubin’s work at the Post, read Eric Alterman’s Nation article from last summer, entitled appropriately “Attack Dog Jennifer Rubin Muddies the Washington Post’s Reputation.”)

Then Cornyn’s remarks are immediately reprinted on the Weekly Standard website and linked to by the National Review’s “Corner” blog. I’m sure Commentary’s Contentions blog will pick them up soon, and maybe we’ll see them on the Wall Street Journal’s editorial page next week. (Today’s lead editorial deals with John Kerry’s appointment, but the thrust is all about the dangers posed by Hagel, whose views are predictably described as “neo-isolationism.”)

]]>

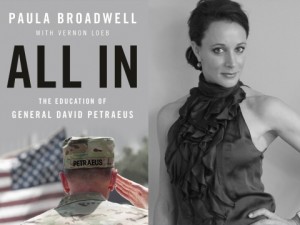

In what is sure to be one of the most glaringly obvious headlines written about the General Petraeus-Paula Broadwell affair, the Washington Post writes: “Petraeus hoped affair would stay secret and he could keep his job as CIA director.”

Clearly, things did not go according to plan. Right after the [...]]]>

In what is sure to be one of the most glaringly obvious headlines written about the General Petraeus-Paula Broadwell affair, the Washington Post writes: “Petraeus hoped affair would stay secret and he could keep his job as CIA director.”

In what is sure to be one of the most glaringly obvious headlines written about the General Petraeus-Paula Broadwell affair, the Washington Post writes: “Petraeus hoped affair would stay secret and he could keep his job as CIA director.”

Clearly, things did not go according to plan. Right after the election, Petraeus submitted his resignation to President Obama after being under investigation by the FBI for months; he had already reportedly broken off his relationship with Broadwell, his biographer.

ABC reports that the FBI did not in fact inform the White House because their findings were “the result of a criminal investigation that never reached the threshold of an intelligence probe” — but even as the FBI was mulling over what to do next, one of the agents on the case was contacting Florida socialite Jill Kelley to inform her of their findings so far.

The investigation showed just how broad the Bureau’s powers are with respect to communications monitoring. Rather than observing what The Daily Beast calls “the spirit of minimization to lead the FBI to keep any personal revelations within the bureau and not say anything to anybody” in other cases involving personal threats, it seems that the since-dismissed agent violated this policy and not only told Kelley, but Members of Congress as well, before the Tampa office handling the email-reading contacted the Director of the FBI to warn of possible national security implications.

As a result of the FBI’s case with Kelley, the US/NATO commander in Afghanistan, General John R. Allen, is also now “involved” in the scandal due to his lengthy email correspondence with Kelley that has raised concerns over potential breaches of national security.

Though the details of the affair have captured headlines and a large number of officials and foreign policy commentators are bemoaning the damage done to Petraeus’s military-policy reputation, some discussion is occurring over the ex-DCIA’s record as top general in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as Langley’s chief drone advocate.

Issandr El Amrani at the Arabist offers a succinct observation of how Petraeus’s star rose in the Beltway hierarchy as the US sought a way out of Iraq: “[h]e delivered results of sorts for the US, which gave Washington political cover for an exit.” While this certainly represented a success for a despairing Bush White House, it was not a step towards carrying out an extended occupation, or even reinvigorating the potpourri of war aims increasingly advanced after 2003 to re-spin the war’s WMD casus belli. Iraq’s ongoing political troubles offer few hints as to how counterinsurgency, or COIN, may have staved off total collapse. At least, from the military’s perspective, the “Surge” staved off a complete collapse and ensured the US could withdraw in the near future, not unlike Nixon’s 1973 “peace with honor” adage in Vietnam. With Iran maintaining its influence in Baghdad (handed to them by the US invasion), disparate militias eyeing each other warily in Kurdistan, and Iraq’s anti-Iranian & anti-American terror cells looking to Syria to revitalize their regional struggle, America’s 21st century “peace with honor” may sound just as hollow for some Iraqi officials today as it sounded for South Vietnamese negotiators back then.

COIN itself never came to reoccupy the spot formerly reserved for “nation-building” in the years Robert McNamara’s whiz kids rode high. As Andrew Sullivan and Michael Hastings note, the general himself did not exactly follow his own press in practice when he transfered over to Afghanistan, emphasizing air strikes and special operations missions over his much-lauded counterinsurgency practices of going door-to-door to win the population over. As Spencer Ackerman, who has issued an apology for not being more aware of how the general’s Army office was influencing his past reporting, Petraeus has done much to expand the CIA’s own drone program, calling for a significant expansion of the program just weeks before his resignation.

COIN and its mythologizing aside, there are few reasons to expect that the general’s counterterrorism policies will suddenly fall out of favor with the White House, not least because Deputy NSA John O. Brennan has been one of the driving forces for institutionalizing drone warfare since his appointment in 2009. The influential former DCIA Michael Hayden, now coming off of his stint as an advisor to former GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney, is urging the agency to move away from its targeted killing trajectory and back towards threat assessment and anticipation. He remarked that looking to the future of the Agency, “[t]he biggest challenge may be the sheer volume of problems that require intelligence input.”

There is little chance though that Petraeus’s downfall will see the downgrading of the Agency’s robot presence. With both the US and Pakistan unwilling to launch ground major operations into the Afghanistan-Pakistan border regions due to the casualties their armed forces would incur, the drone wars are regarded as the most effective military option available. Neither Washington nor Islamabad — or on the other side of the Indian Ocean, Sana’a and Mogadishu — have either the capacity or will for anything more. Or for anything less, in fact, since that would mean ceding the field to the targets, who despite their losses, can draw strength from these strikes. The CTC man told the Washington Post last year while the Agency may be “killing these sons of bitches faster than they can grow them now,” he himself does not think he’s implementing a truly sustainable policy for this Administration, or for those that will follow.

But as the Post reported this past month, Deputy NSA Brennan seems to think otherwise, along with those reportedly elevated in the CIA under Petraeus’s directorship.

While the relationship between reporter and officer — whether sexualized or not — is likely to remain a topic of debate and “soul-searching” for commentators in the coming months, and COIN may fade away from Army manuals trying to plan out the next “time-limited, scope-limited military action, in concert with our international partners,” the new face of counterterrorism that is the General Atomics MQ series is likely to be the general/DCIA’s most lasting legacy. And this will be the one that holds the fewest headlines of all in the weeks to come, given it’s broad acceptance across both major parties and the “punditocracy.”

]]>The International Crisis Group has issued a report strongly critical of the expectations being advanced by US policymakers that Afghanistan will be “stable” enough by 2014 for a handover of national security to Kabul:

A repeat of previous elections’ chaos and chicanery would trigger a constitutional crisis, lessening chances the present [...]]]>

The International Crisis Group has issued a report strongly critical of the expectations being advanced by US policymakers that Afghanistan will be “stable” enough by 2014 for a handover of national security to Kabul:

The International Crisis Group has issued a report strongly critical of the expectations being advanced by US policymakers that Afghanistan will be “stable” enough by 2014 for a handover of national security to Kabul:

A repeat of previous elections’ chaos and chicanery would trigger a constitutional crisis, lessening chances the present political dispensation can survive the transition. In the current environment, prospects for clean elections and a smooth transition are slim. The electoral process is mired in bureaucratic confusion, institutional duplication and political machinations. Electoral officials indicate that security and financial concerns will force the 2013 provincial council polls to 2014. There are alarming signs Karzai hopes to stack the deck for a favoured proxy. Demonstrating at least will to ensure clean elections could forge a degree of national consensus and boost popular confidence, but steps toward a stable transition must begin now to prevent a precipitous slide toward state collapse. Time is running out.

Institutional rivalries, conflicts over local authority and clashes over the role of Islam in governance have caused the country to lurch from one constitutional crisis to the next for nearly a decade. As foreign aid and investment decline with the approach of the 2014 drawdown, so, too, will political cohesion in the capital.

…. Although Karzai has signalled his intent to exit gracefully, fears remain that he may, directly or indirectly, act to ensure his family’s continued majority ownership stake in the political status quo. This must be avoided. It is critical to keep discord over election results to a minimum; any move to declare a state of emergency in the event of a prolonged electoral dispute would be catastrophic. The political system is too fragile to withstand an extension of Karzai’s mandate or an electoral outcome that appears to expand his family’s dynastic ambitions. Either would risk harming negotiations for a political settlement with the armed and unarmed opposition. It is highly unlikely a Karzai-brokered deal would survive under the current constitutional scheme, in which conflicts persist over judicial review, distribution of local political power and the role of Islamic law in shaping state authority and citizenship. Karzai has considerable sway over the system, but his ability to leverage the process to his advantage beyond 2014 has limits. The elections must be viewed as an opportunity to break with the past and advance reconciliation.

Quiet planning should, nonetheless, begin now for the contingencies of postponed elections and/or imposition of a state of emergency in the run up to or during the presidential campaign season in 2014. The international community must work with the government to develop an action plan for the possibility that elections are significantly delayed or that polling results lead to prolonged disputes or a run-off. The International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) should likewise be prepared to organise additional support to Afghan forces as needed in the event of an election postponement or state of emergency; its leadership would also do well to assess its own force protection needs in such an event well in advance of the election.

All this will require more action by parliament, less interference from the president and greater clarity from the judiciary. Failure to move on these fronts could indirectly lead to a political impasse that would provide a pretext for the declaration of a state of emergency, a situation that would likely lead to full state collapse. Afghan leaders must recognise that the best guarantee of the state’s stability is its ability to guarantee the rule of law during the political and military transition in 2013-2014. If they fail at this, that crucial period will at best result in deep divisions and conflicts within the ruling elite that the Afghan insurgency will exploit. At worst, it could trigger extensive unrest, fragmentation of the security services and perhaps even a much wider civil war. Some possibilities for genuine progress remain, but the window for action is narrowing.

Both the Obama Administration and Romney campaign have committed themselves to completing the handover by 2014.

]]>In an interview with CBS’s 60 Minutes, the U.S. military commander atop international forces in Afghanistan said U.S. forces would not be leaving the war-torn Central Asian country any time soon. The comments by Gen. John Allen, who took command of the International Security Assistance Force [...]]]>

In an interview with CBS’s 60 Minutes, the U.S. military commander atop international forces in Afghanistan said U.S. forces would not be leaving the war-torn Central Asian country any time soon. The comments by Gen. John Allen, who took command of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) when Gen. David Petraeus stepped down to take the helm of the C.I.A. in July, fall in line with other U.S. and international officials since President Obama announced in June that a complete transition to Afghan security responsibility would take place by the end of 2014.

CBS’s Scott Pelley asked Gen. Allen what his plan for Afghanistan was:

- ALLEN: Well the plan is to – is to win. The plan is to be successful and the United States is gonna be here for some period of time.

PELLEY: …You’re talking about U.S. forces being here after 2014?

ALLEN: Yes, there will be.

PELLY: …Are we talking about fighting forces?

ALLEN: We’re talking about forces that will provide an advisory capacity. And we may even have some form of counter-terrorism force here to continue the process of developing the Afghan’s counter-terrorism capabilities. But, if necessary, respond ourselves.

PELLEY: But what you’re saying is that the United States isn’t leaving Afghanistan in the foreseeable future?

ALLEN: Well that’s an important message.

As for specific numbers of U.S. forces that will remain, Allen said it was “too early to tell.”

Also in the 60 Minutes segment, U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan Ryan Crocker, in response to a direct question form Pelley, offered a veiled acknoweldgement that the U.S. was talking to at least some factions of the Taliban-led insurgency: “[W]e talk to the whole range of people, anyone who will talk to us. You can draw your own conclusions.”

Allen recounted a recent episode where he’d gone to Pakistan to ask the top military commander there, Gen. Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, to help stop a truck bomb that U.S. intelligence indicated was travelling from Pakistan to Afghanistan to target U.S. troops. “We think it ultimately exploded against the outer wall of one of our combat outposts,” said Allen. “Seventy-seven [Americans] were wounded that day.”

]]>