The book “Preparing For The Day After” is a photojournalistic treatise, a veritable treat for the newshound published on the eve of the 10th anniversary of the Asian Tsunami as an E Book on Google Play. Taking off on a critique on the role of the media on [...]]]>

The book “Preparing For The Day After” is a photojournalistic treatise, a veritable treat for the newshound published on the eve of the 10th anniversary of the Asian Tsunami as an E Book on Google Play. Taking off on a critique on the role of the media on the day of the tsunami, the author substantiates media’s ignorance and paralysis with official U.N. reports.

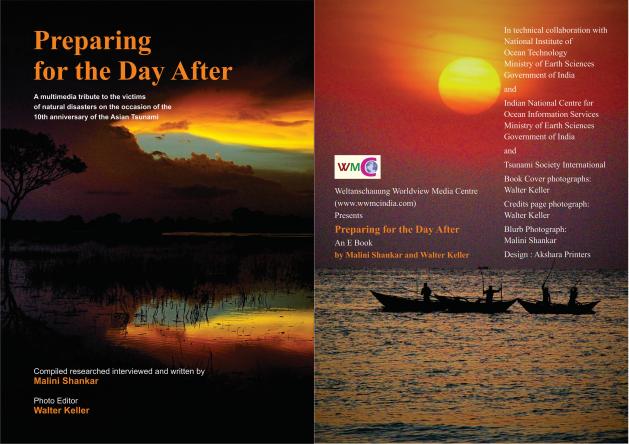

Preparing for the Day After: A Picture E Book on Disaster Management

Malini Shankar

The E book is an authoritative analysis and compendium of the evolution of disaster management, the concept of disaster risk reduction, which evolved as a post script to humanity’s biggest recorded disaster – the Asian tsunami.

Issues such as culture sensitive food security, administrative coordination, mass mortality management, impact of calamities on agriculture, livelihood, fisheries, bio diversity etc. have been authenticated with news reports, interviews, official reports, scientific perspective and pictures to make this work a credible, aesthetic, authoritative and attractive literature in a current affairs perspective.

What makes it so attractive as a Picture Handbook online is its endless repertoire of referenced links to official U.N. and country reports, news media articles and visualisation with never before seen pictures and Street view graphics from Google Earth, Pacific Tsunami Warning Centre, Global Volcanism Programme of Smithsonian Institutions, NOAA, USGS, Ministry of Defence, Government of India, Swiss Avalanche Forecasting Establishment, Agencia Brazil etc.

There is a credible attempt at exposing what may be either corruption, missing links, dereliction of duty or nepotism in implementing actionable inputs of early warning. Lacunae in standard operating procedures of early warning in South Asia have been exposed.

The author has also articulated a geological perspective of climate change which often escapes the attention of the mainstream media. That is a very fresh breathe of air… for as the book title suggests it is not at all a doomsday prophecy rather it is a positive learning experience with vigorous illustrated documentation. In all, the book makes a veritable storehouse of well researched data on natural calamities.

Evolution of best practises can have far reaching consequences on diplomacy in South Asia. A south Asian version of meals on wheels to mitigate starvation with the cultural diversity of Asiatic cuisine has an unimaginable amount of goodwill, economic and diplomatic scope.

Indeed it can be a game changer. Convergence of economic and military might on the high seas for humanitarian mission? Is it naïveté or brilliance? I was unable to decide. But the compelling logic makes it a gripping read in lucid yet powerful text.

Some first person accounts take the reader effortlessly to the forlorn locales like the high seas on Campbell Bay or Sunda Straits. Reading those accounts are enigmatic and addictive, the kind of books ideal during travel for lay persons and serious library referencing for trainee administrators, NGOs and disaster managers in any part of the globe, I can assure you!

Besides the fund of information housed in this literature, another aspect which appeals is the rich narratives of human triumph and tragedy. Most lay persons only remember seeing visuals on TV showing the damage done by the monster waves of the Asian tsunami. Few people are able to get an inside view of the survivor’s mind, body and psyche of a tsunami survivor.

The author through her interactions and interviews with a range of brave hearts who survived the trauma, has sensitively brought home the awareness of just what all entails being a survivor of a disaster of this magnitude; and the ramifications of such a disaster on human souls, which unfolds over years. There is a picture of a cat hiding from scare of a seismic event… there is a picture of a dead cow entangled in the roots of a mangrove forest.

The book also serves as an awareness manual to the common man to get a sense of how delicate the balance in nature is… And just how ruthless and ferocious Mother Nature can be.

A downside is the size of the E book. At 1332 pages it doesn’t make for a quick read, all of which is encapsulated in two words! – “Go Green”. But the author explained that this is because it is an E Book. Once designed for a hard copy printed edition, it should be far less, but of encyclopaedic proportions I am sure!

Also the author could have treated climate change with a lot more of serious attention it calls for; although it is touched up as sub text in various chapters. Said Shankar, in an exclusive discussion with this writer “Even U.N. reports like SREX cannot be a complete and exhaustive compilation of extreme weather events; how then can one unfunded author put it together? Hence I created an online Survey seeking best practices on mitigating hydrometeorological disasters”.

Looking at the alphabetical listing of hydrometeorological disasters in “Preparing For The Day After”, it is obviously a challenge to compile all HM disasters with research reports, field anecdotes, quotes, best practices, pictures, dissertation etc on a global scale in one picture handbook that too without funding by one author.

With photographs sourced from Government of India, Government of Switzerland Government of Brazil, U.N. Photo Library, and another 8 photographers, the illustration is a very rich kaleidoscope of Disaster Management issues. The graphic images of mass graves, mass mortalities have been handled with sensitivity and cannot be called sensational. The book’s photojournalistic value comes out perfectly synchronous to the copious text. Illustration and text both justify the portraiture of disaster management issues.

All in all, an informative and interesting read, needs editing though if it needs to reach the unconverted clichéd “illiterate vulnerable communities”. However the critical significance of the book justifies multilingual editions for a global reach. It’s a shame that a work of this genre lacked funding and had to compromise on research or printing costs. Google Play Books has universal reach no doubt but its technical accessibility can be challenging, denying the critical reach of the work to the ones to whom it matters the most.

The E Book is available only on Google Play App on smartphones on this link: https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=EbzkBQAAQBAJ

Author credits:

Researched, compiled, interviewed photographed and written by Malini Shankar

Photo Editor: Walter Keller.

via IPS News

It’s no wonder that Egypt has floundered in its efforts to create a more democratic system from the ruins of the Mubarak regime.

A sweeping new history of Middle Eastern political activists shows that the search for justice has deep roots in the region but has often been thwarted [...]]]>

via IPS News

It’s no wonder that Egypt has floundered in its efforts to create a more democratic system from the ruins of the Mubarak regime.

A sweeping new history of Middle Eastern political activists shows that the search for justice has deep roots in the region but has often been thwarted by the intervention of foreign powers.

The Arab Spring revolts of 2011 were “both improbable and long in the making,” writes Elizabeth Thompson in her book, “Justice Interrupted: The Struggle for Constitutional Government in the Middle East.”

The young people who massed in Tahrir Square and overturned the U.S.-backed Mubarak dictatorship were the heirs of Col. Ahmad Urabi, whose peasant army was crushed in 1882 by British troops. The beneficiaries of 2011 so far, however, are the heirs of Hassan al-Banna, the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, whose concept of “justice” appears to restrict the rights of women, religious minorities and secular groups.

On Tuesday, President Mohamed Morsi’s own legal adviser resigned to protest a law that would force the retirement of more than 3,000 judges – Mubarak appointees that have sought to blunt the rising influence of Islamist politicians such as Morsi. The United States, while criticising human rights abuses under the new regime, appears to be placing a higher priority on Egypt maintaining its peace treaty with Israel.

If, as President Barack Obama likes to say – quoting Martin Luther King – “the arc of history bends toward justice” – in the Middle East, that arc has been exceedingly long.

The breakup of the Ottoman Empire after World War I interrupted movements for constitutional government and tainted liberalism by association with Western colonialism. Military autocrats, nationalists and Islamic groups took their place.

Thompson, a professor of Middle Eastern history at the University of Virginia, structures her book by compiling mini-biographies of strivers for justice beginning with an early Ottoman bureaucrat, Mustafa Ali, who wrote a critique of corruption in Egypt, and ending with Wael Ghonim.

Ghonim, a Google executive, created a Facebook page devoted to a young Egyptian beaten to death in 2010 by police that attracted 300,000 followers – many of whom later gathered in Tahrir Square.

Others profiled in the book include Halide Edib, known as Turkey’s “Joan of Arc,” who first supported, then opposed Kemal Ataturk’s dictatorship; Yusuf Salman Yusuf or “Comrade Fahd,” whose Iraqi Communist Party was the largest and most inclusive political movement in modern Iraqi history; and Ali Shariati, the Iranian Islamic Socialist whose ideals were hijacked by the clerical regime after the 1979 revolution.

At a book launch Tuesday at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Thompson was asked by IPS if her book was largely a “history of losers” and whether there was any way to break the dismal cycle of one step forward, two steps back toward effective, representative government in the Middle East.

She compared recent revolts in the region to the 1848 revolutions in Europe that failed at the time but were key precursors of democratic movements to follow.

“You have to think long term,” she said. The optimistic interpretation of the Arab Spring is that it has led to “a fundamental shift in the political culture that will bear fruit decades later.”

She conceded that the current picture in Egypt is not a happy one.

Women, who in 2011 figured prominently in the overthrow of Mubarak, are now afraid to go to Tahrir Square for fear of being molested by thugs. Morsi, the president who hails from the Muslim Brotherhood, “is in a defensive posture,” Thompson said, “playing to the Salafist right.” Meanwhile, “the poor and the Copts are losing out.”

However, the Egyptian press has never been so free and Middle Easterners in general are more exposed to information than at any time in their history, she said. “People are not sealed off like they were in Syria in 1989” when state-run media omitted news that the Berlin Wall had fallen, she said.

Still, time and again in the last 150 years, the desire for security and independence from foreign powers has trumped liberal conceptions of human rights.

Thompson’s book contains many tantalising “What ifs” often linked to foreign machinations.

What if France had permitted Syria to retain an independent constitutional monarchy under King Feisal after World War I? French troops instead occupied the country under an internationally blessed mandate that lasted until after World War II.

What if Akram al-Hourani, leader of the Arab Socialist Party in Syria after independence, had not agreed to union with Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Egypt in 1958? Nasser proceeded to outlaw Syrian political parties and in 1963, the Baath party staged a coup and installed a regime that is fighting for its existence today.

The book also sheds light on important figures such as the Palestinian Salah Khalaf, Yasser Arafat’s number two who was known as Abu Iyad. Assassinated in 1991 by the rejectionist Abu Nidal faction, Iyad had made the transition from terrorist mastermind to supporter of the two-state solution for Israel and Palestine. Arafat, who used to rely on Khalaf’s advice, might have steered his movement more wisely in his later years if he had not lost Abu Iyad as well as PLO military commander, Abu Jihad, who was killed by Israelis in 1988.

If, as Thompson concludes, the Arab Spring “has reprised the struggle interrupted by the World Wars and the Cold War,” it is a struggle that is still far from being won.

Photo: Protests across Egypt have not brought a right to information. Credit: Khaled Moussa al-Omrani.

]]>via IPS News

A review of Flynt Leverett and Hillary Mann Leverett’s “Going to Tehran: Why the United States Must Come to Terms with the Islamic Republic of Iran” (Metropolitan Books, 2013)

“Going to Tehran” arguably represents the most important work on the subject of U.S.-Iran relations to be published thus [...]]]>

via IPS News

A review of Flynt Leverett and Hillary Mann Leverett’s “Going to Tehran: Why the United States Must Come to Terms with the Islamic Republic of Iran” (Metropolitan Books, 2013)

“Going to Tehran” arguably represents the most important work on the subject of U.S.-Iran relations to be published thus far.

Flynt Leverett and Hillary Mann Leverett tackle not only U.S. policy toward Iran but the broader context of Middle East policy with a systematic analytical perspective informed by personal experience, as well as very extensive documentation.

More importantly, however, their exposé required a degree of courage that may be unparalleled in the writing of former U.S. national security officials about issues on which they worked. They have chosen not just to criticise U.S. policy toward Iran but to analyse that policy as a problem of U.S. hegemony.

Both wrote memoranda in 2003 urging the George W. Bush administration to take the Iranian “roadmap” proposal for bilateral negotiations seriously but found policymakers either uninterested or powerless to influence the decision. Hillary Mann Leverett even has a connection with the powerful American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), having interned with that lobby group as a youth.

After leaving the U.S. government in disagreement with U.S. policy toward Iran, the Leveretts did not follow the normal pattern of settling into the jobs where they would support the broad outlines of the U.S. role in world politics in return for comfortable incomes and continued access to power.

Instead, they have chosen to take a firm stand in opposition to U.S. policy toward Iran, criticising the policy of the Barack Obama administration as far more aggressive than is generally recognised. They went even farther, however, contesting the consensus view in Washington among policy wonks, news media and Iran human rights activists that President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s election in June 2009 was fraudulent.

The Leveretts’ uncompromising posture toward the policymaking system and those outside the government who support U.S. policy has made them extremely unpopular in Washington foreign policy elite circles. After talking to some of their antagonists, The New Republic even passed on the rumor that the Leveretts had become shills for oil companies and others who wanted to do business with Iran.

The problem for the establishment, however, is that they turned out to be immune to the blandishments that normally keep former officials either safely supportive or quiet on national security issues that call for heated debate.

In “Going to Tehran”, the Leveretts elaborate on the contrarian analysis they have been making on their blog (formerly “The Race for Iran” and now “Going to Tehran”) They take to task those supporting U.S. systematic pressures on Iran for substituting wishful thinking that most Iranians long for secular democracy, and offer a hard analysis of the history of the Iranian revolution.

In an analysis of the roots of the legitimacy of the Islamic regime, they point to evidence that the single most important factor that swept the Khomeini movement into power in 1979 was “the Shah’s indifference to the religious sensibilities of Iranians”. That point, which conflicts with just about everything that has appeared in the mass media on Iran for decades, certainly has far-reaching analytical significance.

The Leveretts’ 56-page review of the evidence regarding the legitimacy of the 2009 election emphasises polls done by U.S.-based Terror Free Tomorrow and World Public Opinon and Canadian-based Globe Scan and 10 surveys by the University of Tehran. All of the polls were consistent with one another and with official election data on both a wide margin of victory by Ahmadinejad and turnout rates.

The Leveretts also point out that the leading opposition candidate, Hossein Mir Mousavi, did not produce “a single one of his 40,676 observers to claim that the count at his or her station had been incorrect, and none came forward independently”.

“Going to Tehran” has chapters analysing Iran’s “Grand Strategy” and on the role of negotiating with the United States that debunk much of which passes for expert opinion in Washington’s think tank world. They view Iran’s nuclear programme as aimed at achieving the same status as Japan, Canada and other “threshold nuclear states” which have the capability to become nuclear powers but forego that option.

The Leveretts also point out that it is a status that is not forbidden by the nuclear non-proliferation treaty – much to the chagrin of the United States and its anti-Iran allies.

In a later chapter, they allude briefly to what is surely the best-kept secret about the Iranian nuclear programme and Iranian foreign policy: the Iranian leadership’s calculation that the enrichment programme is the only incentive the United States has to reach a strategic accommodation with Tehran. That one fact helps to explain most of the twists and turns in Iran’s nuclear programme and its nuclear diplomacy over the past decade.

One of the propaganda themes most popular inside the Washington beltway is that the Islamic regime in Iran cannot negotiate seriously with the United States because the survival of the regime depends on hostility toward the United States.

The Leveretts debunk that notion by detailing a series of episodes beginning with President Hashemi Rafsanjani’s effort to improve relations in 1991 and again in 1995 and Iran’s offer to cooperate against Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan and, more generally after 9/11, about which Hillary Mann Leverett had personal experience.

Finally, they provide the most detailed analysis available on the 2003 Iranian proposal for a “roadmap” for negotiations with the United States, which the Bush administration gave the back of its hand.

The central message of “Going to Tehran” is that the United States has been unwilling to let go of the demand for Iran’s subordination to dominant U.S. power in the region. The Leveretts identify the decisive turning point in the U.S. “quest for dominance in the Middle East” as the collapse of the Soviet Union, which they say “liberated the United States from balance of power constraints”.

They cite the recollection of senior advisers to Secretary of State James Baker that the George H. W. Bush administration considered engagement with Iran as part of a post-Gulf War strategy but decided in the aftermath of the Soviet adversary’s disappearance that “it didn’t need to”.

Subsequent U.S. policy in the region, including what former national security adviser Bent Scowcroft called “the nutty idea” of “dual containment” of Iraq and Iran, they argue, has flowed from the new incentive for Washington to maintain and enhance its dominance in the Middle East.

The authors offer a succinct analysis of the Clinton administration’s regional and Iran policies as precursors to Bush’s Iraq War and Iran regime change policy. Their account suggests that the role of Republican neoconservatives in those policies should not be exaggerated, and that more fundamental political-institutional interests were already pushing the U.S. national security state in that direction before 2001.

They analyse the Bush administration’s flirtation with regime change and the Obama administration’s less-than-half-hearted diplomatic engagement with Iran as both motivated by a refusal to budge from a stance of maintaining the status quo of U.S.-Israeli hegemony.

Consistent with but going beyond the Leveretts’ analysis is the Bush conviction that the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq had shaken the Iranians, and that there was no need to make the slightest concession to the regime. The Obama administration has apparently fallen into the same conceptual trap, believing that the United States and its allies have Iran by the throat because of its “crippling sanctions”.

Thanks to the Leveretts, opponents of U.S. policies of domination and intervention in the Middle East have a new and rich source of analysis to argue against those policies more effectively.

*Gareth Porter, an investigative historian and journalist specialising in U.S. national security policy, received the UK-based Gellhorn Prize for journalism for 2011 for articles on the U.S. war in Afghanistan.

Photo: Tehran skyline in Iran.

]]>via IPS News

NEW YORK, Nov 26 2012 (IPS) - I have never read a book quite like this. “Becoming Enemies” is the latest product of the indispensable National Security Archive, the Washington non-profit that has given new meaning to the Freedom of Information Act.

They not only use their [...]]]>

via IPS News

NEW YORK, Nov 26 2012 (IPS) - I have never read a book quite like this. “Becoming Enemies” is the latest product of the indispensable National Security Archive, the Washington non-profit that has given new meaning to the Freedom of Information Act.

NEW YORK, Nov 26 2012 (IPS) - I have never read a book quite like this. “Becoming Enemies” is the latest product of the indispensable National Security Archive, the Washington non-profit that has given new meaning to the Freedom of Information Act.

They not only use their skills to get major U.S. policy documents declassified, but they take those documents and find innovative ways to illuminate important historical episodes. This book is a living example.

It covers the period of the Iran-Iraq war, during which U.S.-Iran relations hardened into the seemingly permanent enmity that has characterised their relations ever since. NSA assembled a group of individuals who were deeply involved in the making of U.S. policy during that time, backed up by a small group of scholars who had studied the period.

They provided them with a briefing book of major documents from the period, mostly declassified memos, to refresh their memories, and then launched into several days of intense and structured conversation. The transcript of those sessions, which the organisers refer to as “critical oral history”, is the core of this book.

No one can emerge from this book without a sense of revelation. No matter how much you may know about these tumultuous years, even if you were personally involved or have delved into the existing academic literature, you will discover new facts, new interpretations, and new dimensions on virtually every page.

I say this as someone who was part of the U.S. decision-making apparatus for part of this time and who has since studied it, written about it, and taught it to a generation of graduate students. I found little to suggest that my own interpretations were false, but I found a great deal that expanded what I knew and illuminated areas that previously had puzzled me. I intend to use it in my classes from now on.

Iranians tend to forget or to underestimate the impact of the hostage crisis on how they are perceived in the world. Many Iranians are prepared to acknowledge that it was an extreme action and one that they would not choose to repeat, but their inclination is to shove it to the back of their minds and move on.

This book makes it blindingly clear that the decision by the Iranian government to endorse the attack on the U.S. embassy in November 1979 and the subsequent captivity of U.S. diplomats for 444 days was an “original sin” in the words of this book for which they have paid – and continue to pay – a devastating price.

Similarly, U.S. citizens tend to forget their casual response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Iran, our tacit acquiescence to massive use of chemical weapons by Iraq, and the shootdown of an Iranian passenger plane by a U.S. warship, among other things.

The authors of “Becoming Enemies” remind us that, just as Americans have not forgotten the hostage crisis, Iranians have neither forgotten or forgiven America’s own behaviour – often timid, clumsy, incompetent, or unthinking; but always deadly from Iran’s perspective.

It is impossible in a brief review to catalogue the many new insights that appear in this book for the first time. However, one of the most impressive sections deals with the so-called Iran-contra affair – the attempt by the Reagan administration to secretly sell arms to Iran in the midst of a war when we were supporting their Iraqi foes.

This, of course, exploded into a major scandal that revealed criminal actions by many of the administration’s top aides and officials and nearly resulted in the impeachment of the president. The official position of the administration in defending its actions was that this represented a “strategic opening” to Iran.

Participants in this discussion, some of whom had never before publicly described their own roles, dismissed that rationale as self-serving political spin. President Reagan, they agreed, was “obsessed” (the word came up repeatedly) with the U.S. hostages in Lebanon and was willing to do whatever was required to get them out, even if it cost him his job.

Moreover, the illegal diversion of profits from Iran arms to support the contra rebels in Central America was, it seems, only one of many such operations. The public focus on Iran permitted the other cases to go unexamined.

Another striking contribution is the decisive role played by the U.N. secretary-general and his assistant secretary, Gianni Picco (a participant), in bringing an end to the Iran-Iraq war. This is a gripping episode in which the U.N. mobilised Saddam’s Arab financiers to persuade him to stop the war, while ignoring the unhelpful interventions of the United States. They deserved the Nobel Peace Prize they received for their efforts.

There are, however, some lapses in this otherwise exceptional piece of research. One of the “original sins” of U.S. policy that are discussed is the U.S. failure to denounce the Iraqi invasion of Iran on Sep. 22, 1980, thereby confirming in Iranian eyes U.S. complicity in what they call the “imposed war”. I am particularly sensitive to the fact that the discussion of the actions of the Carter administration in 1980 is conducted in the absence of anyone who was actually involved.

Those of us in the White House at the time would never have failed to recall that direct talks with the Iranians about the release of the hostages had begun only days earlier. So there was for the first time in nearly a year a high-level authentic negotiating channel with Iran.

My own contribution to the missed opportunities that are enumerated at the end of the book would, in retrospect, have been our lack of courage or imagination to use our influence with the United Nations Security Council to bargain with Iran for immediate action on the hostages. If we had taken a principled position calling for an immediate cease-fire and Iraqi withdrawal, the entire nature of the war could have been transformed.

To my surprise, Zbigniew Brzezkinski, my boss at the time, sent a personal memo to President Carter (which I had never seen until now) that argued for “Iran’s survival” and held out the possibility of secret negotiations with Tehran. This was a total revelation to me, and it was so contrary to the unfortunate conventional wisdom that Brzezkinski promoted the Iraqi invasion that even the authors of this book seemed at a loss to know what to make of it.

The other huge disappointment with this initiative, which is not the fault of the organisers, was the absence of any Iranian policymakers. Iranian leaders and scholars should read this book. Perhaps one day their domestic politics will permit them to enter into such a dialogue. That day is long overdue.

*Gary Sick is a former captain in the U.S. Navy, who served as an Iran specialist on the National Security Council staff under Presidents Ford, Carter, and Reagan. He currently teaches at Columbia University. He blogs at http://garysick.tumblr.com.

]]>National Security and Nuclear Diplomacy was published in Iran during the autumn of 2011 but most people only learned about it a few months ago after it was made available during Tehran’s International Book Fair in May. It’s significant because the author is Hassan Rowhani, the country’s nuclear negotiator for 22 [...]]]>

National Security and Nuclear Diplomacy was published in Iran during the autumn of 2011 but most people only learned about it a few months ago after it was made available during Tehran’s International Book Fair in May. It’s significant because the author is Hassan Rowhani, the country’s nuclear negotiator for 22 months during the Khatami presidency – just one of the many positions he has held since the inception of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The book – a publication of the Center for Strategic Studies (CSR), which Rowhani directs – is now in its third printing. CSR is affiliated with the Expediency Council in which Rowhani continues to be a member.

National Security and Nuclear Diplomacy was published in Iran during the autumn of 2011 but most people only learned about it a few months ago after it was made available during Tehran’s International Book Fair in May. It’s significant because the author is Hassan Rowhani, the country’s nuclear negotiator for 22 months during the Khatami presidency – just one of the many positions he has held since the inception of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The book – a publication of the Center for Strategic Studies (CSR), which Rowhani directs – is now in its third printing. CSR is affiliated with the Expediency Council in which Rowhani continues to be a member.

Going beyond the nuclear issue, I recommend this book to anyone who is interested in understanding Iran’s post-revolutionary politics and how the fundamental changes in its structure of power have transformed the decision-making process in the country from one-man rule to a collective enterprise.

The details revealed in Rowhani’s book about how decisions were made in restarting Iran’s nuclear program in the late 1980s, as well as in negotiations with the EU 3 (Britain, Germany and France) are very interesting. The section explaining why negotiations failed with the EU 3, titled “Why Europe Could not Capitalize on the Opportunity?”, should be read by anyone who believes that Iranian negotiators had no reason to be suspicious of the EU 3’s intent and mode of operation. Those interested in learning about the dynamics of Iran’s national security calculus will also find ample information about the changes that occurred in the Supreme National Security Council after 9/11 and Rowhani’s take on why these changes are not sufficient to overcome some basic flaws in Iran’s decision-making process. Rowhani’s opinions about wrong policy choices made by subsequent nuclear teams are also included in National Security and Nuclear Diplomacy.

But the value of this book really lies first in the fact that it was written with a domestic audience in mind and second in the frank defense – and by implication promotion – of that approach to the same domestic audience. But let me be clear that by “domestic audience” I do not necessarily mean the Iranian population at large whose views about national security are, like in every other country, shaped more by the national security establishment than the other way around. More than anything else, this is a book generated from debates and disagreements within Iran’s political establishment that is intended to influence the continuing mutation of that debate. After all, today, the Khatami era nuclear negotiators are routinely accused of passivity, even treason, by Iran’s hard-line security establishment.

Less than two weeks ago, during a meeting with Iranian officials, the Leader Ali Khamenei stated that the EU 3 would not even agree to the Iranian offer of “only 3 centrifuges running” and that had he not intervened in the nuclear file, the Iranian “retreat” would have continued. But unlike Rowhani’s other detractors, Khamenei does acknowledge that the failed negotiation with the EU 3 was a needed experience. And, by using direct quotes from Khamenei, this is a point that Rowhani keeps highlighting: every decision made on the nuclear dossier was made by consensus and had Khamenei’s endorsement. Moreover, preventing the referral of Iran’s nuclear dossier to the UN Security Council at a time when the US was at the height of its military adventurism was a major achievement that assured Iran’s security and also provided the country with time to prepare for future challenges.

However, the defense of his nuclear team’s performance is not the only aspect of Rowhani’s book. He not only sheds light on the nature of domestic opposition to the 2003-05 nuclear negotiations (political as well as based on ignorance about Iran’s posture in the negotiations), he also criticizes the mistakes made by subsequent negotiating teams. Rowhani chastises, for example, the Larijani-led team for thinking that there was no need to continue negotiations with Europe despite his warning that reliance only on the “East” – read Russia and China – was a mistake. He also suggests that the new nuclear team did not take seriously enough the “very dangerous” September 2005 resolution of the International Atomic Energy Association’s (IAEA) board of governors. Rowhani states flatly, “it was after September 2005 that the new nuclear team realized the [limited] weight of the East! And then they went looking for the West, which was of course already too late.”

As to Iran’s current predicament, Rowhani acknowledges Iran’s technological progress: “We can say that 20 percent enrichment has in some ways created increased deterrence”. But he adds that given the “heavy cost paid”, Iran’s technology “should have progressed more.” More significant is Iran’s undesirable political and legal struggle given the referral of Iran’s file to the Security Council. Rowhani concludes National Security and Nuclear Diplomacy by stating:

…now taking [Iran’s file] out of the Security Council is a complex and costly affair. In effect, we have endured the biggest harm in the areas of development and national power. We may have not benefitted much on the whole in terms of national security either. The foundation of security is not feeling apprehensive. In the past 6 years, the feeling of apprehension has not been reduced.

Rowhani does not challenge Iran’s nuclear posture. He is a committed member of the Islamic Republic and supporter of its nuclear program in the face of what he considers to be recalcitrant hostility. His criticism is quite different than the criticism of those – mostly among the Iranian Diaspora – who have challenged the utility of Iran’s nuclear program or the objectives of Iran’s rulers. His charge is much more ordinary and damning: the subsequent nuclear teams made key mistakes, miscalculated, and politicized the nuclear dossier in order to enhance their domestic standing and harmed the interests of the Islamic Republic during the process.

Given the fact that, according to Rowhani, none of the nuclear decisions made in Iran could be made without Khamenei’s endorsement, this book is also a devastating critique of the latter’s endorsement of the clumsy way Iran has negotiated with West.

Rowhani may be right or wrong in arguing that Iran’s condition would have been different with better Iranian negotiators, a better understanding of Iran’s predicament and limitations in finding allies, and better diplomacy. After all, the American and European posture of no enrichment in Iran has persisted with or without Rowhani.

What I do not doubt, however, is the fact that no one could have published a book like this before the revolution!

]]>Cold war liberalism’s multilateralism was a secondary feature of an approach defined more fundamentally by its Manicheanism. Its theoretical foundation relied in great part on the concept of “totalitarianism,” which elided the distinction between communism and fascism and could be taken to justify nearly any form of power politics on moral grounds. If the need to defeat the Axis had authorized Dresden and Hiroshima, as most cold warriors generally agreed that it had, then what could the threat of communism not justify? The result was that the Wilsonian imperative to make the world safe for democracy did not necessarily entail making the world safe through democracy, as demonstrated by the US-backed decapitation of democratic regimes in Guatemala, Iran, Chile, and elsewhere.

The Manichean impulse was neoconservatism’s most important inheritance from the cold war. Totalitarianism, with its rigid dualism, remained the central concept: each enemy a Hitler, each compromise a Munich, the only models Churchill and Chamberlain. Neoconservatism has no aversion to realpolitik, contrary to what is sometimes said, but it does conceive of the enemy in starkly different terms than the conservative realist. For the realist, interests are finite and enemies rational, and the most attractive possibility in such a world is often to strike a deal. For the neoconservatives, however, the enemy is always totalitarian, and any compromise can only offer temporary respite before a final confrontation. The need to defeat the enemy is not merely a pragmatic imperative, but a moral one; not only is the national interest at stake, but the fate of the entire free world. Every mission is messianiac; every struggle is millennial. Norman Podhoretz split the last seventy-five years of global history into World War II (the struggle against fascism), World War III (the struggle against communism), and the ongoing World War IV (the struggle against “Islamofascism”); this periodization veered close to self-parody, but it captured the essence of the neocon Weltanschauung.

Thus it was in response to Henry Kissinger’s pursuit of detente that the original neoconservative hawks clustered around Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson mobilized to fight even the slightest intimation of compromise. More recently, Robert Kagan, the smartest and most systematic thinker of the younger generation of neoconservatives, has attempted to resuscitate a kind of great power politics built around the idea of an overriding conflict between the democratic and non-democratic worlds—most imminently, between the US on one hand and China and Russia on the other. Yet as Francis Fukuyama (himself a recovering neocon) has pointed out, any traditional notion of great power politics is fundamentally alien to the neoconservative sensibility, since the great power vision posits a rational enemy with whom it is possible to do business. It is precisely because of the need for a totalitarian adversary that neoconservatives and their allies among the liberal hawks have been so insistent on the strained portmanteau of “Islamofascism” in the post-September 11 era, aiming to shoehorn the war on terror into the conceptual framework of the struggles against fascism and communism. Without such an adversary, it becomes much harder to square the circle between ruthless means and moralized ends.

What about democracy? As with other elements of the neoconservative mythology, the image of neocons as ardent Wilsonian democracy promoters has been propagated by both supporters and opponents. If neoconservatives have claimed the mantle of “democracy” in order to portray themselves as idealistic do-gooders, their critics have often been happy to cede the point in order to convict the neocons of naivete—which seems to be considered the only unforgivable sin in Washington foreign policy circles. Critics of the Iraq war, in particular, were often reluctant to couch their opposition in explicitly moral terms for fear of appearing soft-headed or otherwise unserious. It seemed far more adult and politically palatable to suggest that the war was foolish than to suggest that it was wrong; in this way, the neocons’ opponents frequently colluded in portraying them as Wilsonian utopians in order to claim the mantle of hard-headed anti-utopianism for themselves.

In fact, there is little to suggest that democracy promotion has ever been at the heart of neooconservatism. The movement’s early programmatic statement, Jeane Kirkpatrick’s 1979 Commentary essay “Dictatorships and Double Standards,” was a call for defending friendly dictators against left-wing popular movements, a course that set the tone for neoconservative foreign policy through the end of the cold war. Once again the theoretical backbone of the argument was furnished by the totalitarian-authoritarian distinction; in practice, Kirkpatrick’s scheme largely collapsed into the distinction between unfriendly left-wing regimes, democratically elected or not, and friendly right-wing ones, no matter how brutal. In recent years democracy promotion has become a more explicit part of the neoconservative program, but one need only look at the Bush Administration’s handling of Egypt and Palestine to see how quickly democratic processes have been scuttled when they have threatened to bring undesirable parties into power.

But check out the whole thing. And, if you can afford it, buy a copy of the magazine.

]]>