by Henry Precht

It seems a shame to let all that fol-de-rol from the Olympics be cast aside after such an abbreviated run. As Sochi revealed to us novices, there are always new, curious forms of sport that merit recognition.

One of those with growing multi-seasonal appeal to large groups of men and [...]]]>

by Henry Precht

It seems a shame to let all that fol-de-rol from the Olympics be cast aside after such an abbreviated run. As Sochi revealed to us novices, there are always new, curious forms of sport that merit recognition.

One of those with growing multi-seasonal appeal to large groups of men and women in the streets is the popular coup or revolution game. Worldwide, these outbreaks — while spontaneous and adopting local rules of engagement — must adhere to certain principles of revolution that have been set forth by seasoned scholars and pundits parachuting in.

Let’s see who garners the top medals in the twelve prescribed categories:

1. Revolution brings together people of disparate ideologies and goals who are united only in seeking to bring down an autocrat; after success only one faction survives and exercises autocratic dominance over the former allies

Gold Medal: Iran; Silver: Egypt; Bronze: Syria (pending)

2. Revolution begins with economic grievances, adds political complaints and, after success, continues in reverse order, i.e., political, then economic gripes

Gold Medal: Tunisia; Silver: Egypt; Bronze: Ukraine (pending)

3. Parliamentary or other opposition with highest potential for splitting off their territory from the nation

Gold Medal: Ukraine Silver: Taliban Bronze: Arizona

4. Outsiders support opposition forces who are (1) long term enemies or (2) become so

Gold Medal: Syria; Silver: Egypt; Bronze: Libya

5. Outsiders cannot remember who is fighting whom or for what purpose

Gold Medal: Thailand; Silver: Yemen; Bronze: Bosnia

6. Opposition pleads for religious or sectarian freedom, but proponents of those virtues do not listen and persist with oppression

Gold Medal: Israel; Silver: Bahrain; Bronze: China (in Tibet)

7. Victorious opposition which has fought for religious freedom later oppresses its fellow citizens

Gold Medal: South Sudan; Silver: Iraq; Bronze: Turkey

8. Most outrageous assertions of guilt of opposition and purity of rulers

Gold Medal: Egypt; Silver: Saudi Arabia; Bronze: Russia

9. Opposition condemns rival party overreach while raking in cash from wealthy power centers

Gold Medal: Tea Party; Silver: Egypt; Bronze: South Africa

10. Highest level of distrust maintained towards its American partner in the struggle against revolutionaries

Gold Medal: Afghanistan; Silver: Israel; Bronze: Egypt

11. Most comfortable middle class opposition movement

Gold Medal: Venezuela; Silver: Turkey; Bronze: Scotland

12. Most determined to kill as many of its own people as necessary to hold or achieve power

Gold Medal: Syria; Silver: Al Qaeda in Iraq/Syria; Bronze: Chechnya

]]>by Jim Lobe

Just 11 days before the annual policy conference of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), the embattled organization got some more bad news, this time in the form of a Gallup poll suggesting that nearly ten years of effort in demonizing Iran in the U.S. public mind [...]]]>

by Jim Lobe

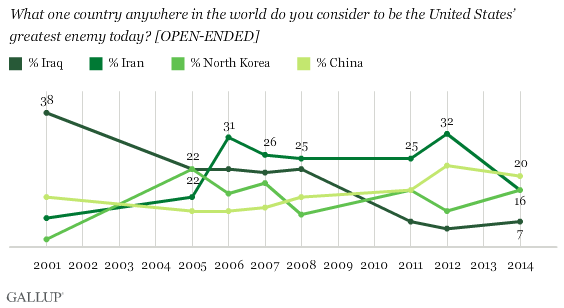

Just 11 days before the annual policy conference of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), the embattled organization got some more bad news, this time in the form of a Gallup poll suggesting that nearly ten years of effort in demonizing Iran in the U.S. public mind may be going down the drain. As Gallup noted in the lede on its analysis of the poll, “Half as many Americans view Iran as the United States’ greatest enemy today as did two years ago.”

Indeed, for the first time since 2006, according to the survey of of more than 1,000 U.S. adults, Iran is no longer considered by the U.S. public to be “the United States’ greatest enemy today.” The relative threat posed by Iran has fallen quite dramatically in just the last two years, the survey found. In 2012, an all-time high of 32 percent of respondents identified Iran as Washington’s greatest foe, significantly higher than the 22 percent who named China. Beijing has now replaced Tehran as the most frequently mentioned greatest threat.” Twenty percent of all respondents cited China, while only 16 percent — or half the percentage of respondents compared to just two years ago — named Iran (which was tied with North Korea).

This is a significant setback for the Israel lobby and AIPAC, which has made Iran the centerpiece of its lobbying activities for the past decade and more, and it should add to the consternation that many of its biggest donors (as well as members) must feel in the wake of its serial defeats on Chuck Hagel, Syria, and, most importantly, on getting new sanctions legislation against Iran last month. As its former top lobbyist, Douglas Bloomfield told me three weeks ago,

Like the old cliche about real estate, ‘Location, location, location,’ for [AIPAC], it’s been ‘Iran, Iran, Iran. Israel and the peace process is in a distant second place.

Now, of course, just as one swallow does not a summer make, one poll can’t be seen as showing a definite trend. But, as you can see from Gallup’s 2001-2014 tracking graph below, the decline in threat perception since 2012 has been remarkably sharp compared, for example, to China’s showing, which has been relatively stable. And the difference between the two nations — 20 percent versus 16 percent — is within the 4-percent margin of error. Still, the fact (brutal as it is for AIPAC) remains: Iran, while still very unpopular (only 12 percent of respondents have a favorable image of it, second in unfavorability only to North Korea), is no longer seen by an important percentage of the population as Washington’s “greatest enemy.”

Moreover, as noted by Gallup’s analysis, “[g]roups that were the most likely to view Iran as the top enemy, such as men, older Americans, and college graduates, tend to show the greatest declines” in seeing Iran as Public Enemy Number One. Younger respondents (aged 18 to 34 years) were least likely to see Iran as the greatest enemy; only nine percent, compared to 21 and 20 percent for China and North Korea, respectively. As for party affiliation, a plurality of Republicans — the party most influenced by neoconservative ideology — still see Iran as the most threatening (20 percent, versus China’s 19 percent); while 23 percent of independents named China as the greatest enemy compared to 16 percent who selected Iran. Among Democrats, 24 percent cited North Korea; only half that percentage named Iran.

Clearly, President Hassan Rouhani and his Foreign Minister Javad Zarif, who dominated U.S. news coverage of Iran during their New York visit in September, as well as progress in negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program, have made a big difference, thus vindicating Benjamin Netanyahu’s (and AIPAC’s) worst fears. No doubt growing tensions between China and its neighbors have also drawn attention away from Iran (which should help, in a somewhat perverse way, Obama’s efforts to “pivot” foreign policy resources more toward Asia), although, as noted above, concern about China has remained relatively stable over the 13 years and actually declined slightly compared to 2012.

Of course, this could also turn around in a flash given the right catalyst. A breakdown in the talks, an incident at sea, or some other unanticipated event could persuade the public that all of the rhetoric about how Iran poses the greatest threat imaginable to the United States and its allies — likely to be amplified at the Washington Convention Center, where AIPAC holds its conference early next month — could propel Tehran back up to the top of the enemies list. But, for now, it’s clear that Netanyahu, who is expected to continue — if not escalate — his aggressive denunciations against the nuclear deal and U.S.-Iranian detente when he comes here to keynote the AIPAC conference, faces a tougher challenge in persuading the American public that Iran poses the greatest threat to U.S. security than at any time since he became Prime Minister. For more on Bibi’s challenges here, read J.J. Goldberg’s editorial in the latest Forward entitled, “Benjamin Netanyahu Tells AIPAC to Put Its Head in a Noose: Pushing American Jews to Take Unpopular Stand on Iran.”

Photo: US Secretary of State John Kerry, EU Foreign Policy Chief Catherine Ashton and Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif’s meeting on the sidelines of the UNGA on Sept. 26, 2013.

]]>After a lovefest in Israel with French President Francois Hollande from Sunday to Tuesday, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu took a shower, packed his suitcase and headed for Moscow, ostensibly to lobby against Russian support for a deal with Iran. He met with Vladimir Putin, held a joint [...]]]>

After a lovefest in Israel with French President Francois Hollande from Sunday to Tuesday, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu took a shower, packed his suitcase and headed for Moscow, ostensibly to lobby against Russian support for a deal with Iran. He met with Vladimir Putin, held a joint press conference with the Russian president, and returned home the same day with little to show for his trouble.

Russia has been providing the weapons that support the Assad regime, and that Israel bombed last week to keep them from getting to Hezbollah. Russia has backed Iran’s claims that its nuclear program is peaceful. Did Netanyahu really think he could change two decades of Russian foreign policy on Iran with a few more hours of haranguing?

“Russia and China were the ones that, until now, did not take action to increase sanctions,” complained Justice Minister Tzipi Livni to Israel Radio. “Therefore it is hard for me to see how, suddenly today, they could be the ones to demand that the world be firmer with the Iranians.”

Most interesting–and revealing–about Netanyahu’s trip to Russia is that he himself made it, and not Israel’s Russia-born foreign minister, Avigdor Lieberman. Lieberman heads Israel’s Yisrael Beiteinu (“Israel is our home”) party–composed largely of Russian emigrants to Israel. Cleared of corruption charges two weeks ago, Lieberman was reinstated as foreign minister on Nov. 11.

During his tenure as foreign minister before the 10- month hiatus that ended a little over a week ago, Lieberman has publicly contradicted Israel’s stated foreign policy positions. During an official visit to China in March 2012, Lieberman declared in a speech that received no coverage in the U.S. press and hardly any in Israel: “If, God forbid, a war with Iran breaks out, it will be a nightmare. And we will all be in it, including the Persian Gulf countries and Saudi Arabia. No one will remain unscathed.”

Lieberman’s 2009 suggestion that Israel should continue to fight Hamas “just like the United States did with the Japanese in World War II” was widely understood to be an allusion to the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with nuclear weapons. Lieberman infuriated Netanyahu, other cabinet ministers and coalition members, as well as opposition leaders, and took the U.S. by surprise,when, in a speech before the UN in 2010, he derided the prospects of a comprehensive peace agreement with the Palestinians as “unrealistic.”

However much he may aggravate Netanyahu, Lieberman is popular because he says aloud what many Israelis feel and many Israeli politicians actually believe. Lieberman’s version of a two-state solution with the Palestinians includes exchanging predominantly Arab towns and villages within “green line” Israel for the major West Bank settlement blocs. Lieberman has called for assassinating the leaders of the Hamas movement in Gaza (something which already has widespread support in theory and practice).

Not surprisingly, Lieberman’s return to the post of Foreign Minister last week was greeted with outrage by the governing coalition’s left-wing opposition and by Arab parties. Meretz chairwoman Zahava Gal-On compared Lieberman’s appointment to head the Foreign Ministry to “planting a bomb in the diplomatic process” that would “further worsen Israel’s poor relations with its allies and its situation in the international community.” Knesset member Jamal Zahalka of the Arab Balad party recommended that Palestinians break off negotiations in response to Lieberman’s reappointment, and MK Ahmed Tibi of the United Arab List-Ta’al opined that Lieberman’s restoration to his post was entirely appropriate for “a government where everyone competes over who will be more fanatic.”

So why did Netanyahu restore Lieberman, whose popularity threatens his own, to such a powerful post? Without Yisrael Beiteinu, which merged with Netanyahu’s Likud party in October 2012 in an effort to revive it, Likud would have been relegated to a relatively minor party in the January 2013 election. Together, the two parties garnered a total of only 31 seats in Israel’s 120-member Knesset (parliament), not the 45-50 seats political pundits had anticipated, and far fewer than they had gotten separately in 2009, when Likud by itself won Knesset 27 seats and Yisrael Beiteinu 15. Votes were diverted to two “young guns” on Israel’s political scene–the ideologically flexible Yesh Atid (“There is a Future”) party and Habayit Heyudai (Jewish Home), an ultra-hawkish right-wing religious nationalist party. Both are demanding more power within the government coalition in keeping with their relative representation in the Knesset.

Without Lieberman, Netanyahu would not have a governing coalition and might be forced to call new elections. As it is, Yisrael Beiteinu is scheduled to meet and discuss the possibility of a divorce from Likud on Nov. 24. There is considerable speculation that Lieberman aspires to the premiership in the not too distant future.

It could be a real game changer for members of both House of the U.S. Congress, Democrats and Republicans, who are deferential, even obsequious toward Netanyahu were the silver-haired, silver-tongued Likud leader to be replaced with a former night-club bouncer with a thick Russian accent who says Israel doesn’t need the U.S. and can find allies elsewhere. In a speech on Nov. 20, Lieberman downplayed the role of the U.S. as Israel’s foremost sponsor: “For many years Israel’s foreign policy was one directional towards Washington, but my policy has many more directions.”

Not European countries, whose foreign policies he would expect to lean against Israel on account of their relatively small Jewish minorities and relatively large Muslim populations. Nor the Gulf Arabs. Instead, according to Lieberman, it would be “countries that don’t need financial assistance and aren’t beholden to the Arab world,” countries that would support Israel out of their own cold and pragmatic interests in gaining access to Israeli high tech innovations, not out of altruism. The most likely candidates for Israel’s New Best Friends: China and Russia.

Meanwhile, Netanyahu, in Russia, not only demonstrated that Israel doesn’t need the U.S. just as well as Avigdor Lieberman could have, but he did it on Lieberman’s native turf. Netanyahu’s Russia visit can be viewed as a pre-emptive strike–not against Iran, but rather against Netanyahu’s frenemy within: the once and future kingmaker, and perhaps even prime minister, Avigdor Lieberman.

]]>

by Jasmin Ramsey

*This post has been updated

Geneva — While diplomats involved in negotiations over Iran’s controversial nuclear program here have been mostly tight-lipped about the details of their meetings, France — which along with Britain, China, Russia and the United States plus Germany composes the so-called P5+1 [...]]]>

by Jasmin Ramsey

*This post has been updated

Geneva — While diplomats involved in negotiations over Iran’s controversial nuclear program here have been mostly tight-lipped about the details of their meetings, France — which along with Britain, China, Russia and the United States plus Germany composes the so-called P5+1 — vocalized today some of its concerns.

Stating that he is interested in an agreement that is “serious and credible”, French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius argued that the “initial text made progress but not enough” during an interview with France Inter radio.

According to François Nicoullaud, France’s former ambassador to Tehran (2001–05), the French position on Iran’s nuclear program has not changed since François Hollande replaced Nicolas Sarkozy on May 12 as President.

“We have a kind of continuity in the French administration where the people who advised Mr. Sarkozy are the same ones who advise the current administration,” the veteran French diplomat told IPS, adding that France’s relations with Iran were more positive during the Jacques Chirac administration.

“This is especially true for the Iranian nuclear case because it’s very technical and complex and the government really needs to be convinced before it changes its position,” he said.

Fabius expressed concerns earlier today over Iran’s enrichment of 20%-grade uranium and its Arak facility, which is not yet fully operational.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who stated that “If the news from Geneva is true, this is the deal of the century for #Iran,” on Nov. 7 from his official Twitter account, has previously accused Iran of trying to build a nuclear bomb byway of its Arak nuclear facility.

“[Iran] also continued work on the heavy water reactor in Arak; that’s in order to have another route to the bomb, a plutonium path,” said Netanyahu during his Oct. 1 speech at the UN General Assembly in New York.

Iran, a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), says its nuclear program is completely peaceful.

While the Obama administration has declared that it will prevent Iran from building a nuclear weapon, the US intelligence community has not officially assessed that Iran has made the decision to do so.

According to the 2013 US Worldwide Threat Assessment, Iran “has the scientific, technical, and industrial capacity to eventually produce nuclear weapons. This makes the central issue its political will to do so.”

Daryl Kimball, the head of the Arms Control Association, says the Arak facility “is more than a year from being completed; it would have to be fully operational for a year to produce spent fuel that could be used to extract plutonium.”

“Iran does not have a reprocessing plant for plutonium separation; and Arak would be under IAEA safeguards the whole time,” he noted in comments printed in the Guardian.

“The Arak Reactor certainly presents a proliferation problem, but there is nothing urgent,” said Nicoullaud, a veteran diplomat who has previously authored analyses of Iran’s nuclear activities.

“The best solution would be to transform it before completion into a light-water research reactor, which would create less problems,” he said, adding: “This is perfectly feasible, with help from the outside.”

“Have we tried to sell this solution to the Iranians? I do not know,” said Nicoullaud.

The unexpected arrival of US Secretary of State John F. Kerry yesterday and all but one of the P5+1’s Foreign Ministers in Geneva — following positive EU and Iranian descriptions here at end of the first day of the Nov. 7-8 talks — led to speculation that some form of an agreement would soon be signed.

While diplomats involved in the talks have provided few details to the media, it’s now become clear that the approximately 6-hour meeting last night between Kerry, Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif and EU Foreign Policy chief Catherine Ashton involved the consideration of a draft agreement presented by the Iranians.

That meeting also contributed to speculation that a document would soon be signed until the early morning hours of Nov. 9, when the LA Times reported that after reaching a critical stage, the negotiators were facing obstacles.

While Western and Iranian diplomats involved in the talks have stated that “progress” has been made, it’s not yet clear whether that has led to a mutually acceptable agreement.

“There has been some progress, but there is still a gap,” Zarif said to reporters earlier today according to the Fars News Agency.

While briefing Iranian media here this afternoon, Zarif acknowledged French concerns but insisted on Iran’s positions.

“We have an attitude and the French have theirs,” said Zarif in comments posted in Persian on the Iranian Student News Agency.

“Negotiation is an approach that is based on mutual respect. If not, they won’t be stable,” he said.

“We won’t allow anyone to compile a draft for us,” said Zarif.

Photo Credit: U.S. Mission Geneva/Eric Bridiers

]]>by Thomas W. Lippman

Whenever a Saudi Arabian king or senior prince publicly criticizes U.S. policy, they inevitably touch off speculation about how the Saudis may be rethinking their security alliance with the United States.

The Saudis have lost confidence in the Americans…the Saudis are fed up with Washington’s support for Israel…The [...]]]>

by Thomas W. Lippman

Whenever a Saudi Arabian king or senior prince publicly criticizes U.S. policy, they inevitably touch off speculation about how the Saudis may be rethinking their security alliance with the United States.

The Saudis have lost confidence in the Americans…the Saudis are fed up with Washington’s support for Israel…The Saudis think the U.S. should have acted sooner…the Saudis think the U.S. should not have intervened…Riyadh is having new conversations with Moscow, or Beijing…the Saudis are looking to diversify their sources of weapons.

A new flurry of such analysis appeared recently when King Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz strongly proclaimed his government’s financial and political support for the military government in Egypt with language that some writers interpreted as critical of the United States.

“Let the entire world know,” he said, “that the people and government of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia stood and still stand today with our brothers in Egypt against terrorism, extremism and sedition, and against whomever is trying to interfere in Egypt’s internal affairs.” Translation: You Americans should stop bleating about democracy in Egypt because all it did was put the Muslim Brotherhood in power, and we won’t accept that.

Examining the king’s statement, Theodore Karasik, director of research at the Dubai-based Institute for Near East & Gulf Military Analysis, said it reflected Saudi anger about other regional issues, not just Egypt:

It’s important to recognize, first of all, that from the Saudi and GCC point of view they see the U.S. as not following through on promises made earlier in the year concerning some type of armed intervention into Syria. Consequently this failure to act has led to the declining victories and growing losses for the Free Syrian Army. It has also allowed a greater Al-Qaeda presence within Syria, which also is troublesome for the region and especially Saudi Arabia and the GCC.

The second point here is that Saudi Arabia and the GCC take Washington’s notion of the strategic pivot very seriously, and their inclination is that they’re being abandoned by Washington in favor of the Pacific theater. That’s their perception regardless of how much equipment is pre-positioned in the Gulf region or how many training programs and weapon sales are going on.

Finally, Saudi Arabia and the GCC are anxious with the possibility that under the new Iranian President Rouhani that there may be a strategic bargain made between Washington and Tehran that would cut out Saudi and GCC security interests. In other words, Saudi Arabia and the GCC feel that they are slowly being pushed aside on what concerns them in the region because of America’s self-interest.

The King’s comments were “unusual,” according to The Guardian, because Abdullah was “aiming his words” at the United States as well as Qatar, which he accused of “fanning the fire of sedition and promoting terrorism, which they claim to be fighting.”

Other commentators offered similar assessments of the king’s apparent irritation with Washington, their views enhanced by speculation over the significance of a July meeting in Moscow between President Vladimir Putin and Prince Bandar bin Sultan, the Saudi intelligence director, which was announced but has not been explained. Could the Saudis have given up on Washington and tried to reach an agreement with the Russians over Syria? (A writer for the Infowars web site, on the other hand, went the other way, reporting that not only did Bandar fail to cut a deal with the Russians to end their support of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, he threatened to arrange terrorist attacks on the upcoming Winter Olympics in Sochi if that support continues.)

It may be true that the rulers of Saudi Arabia are unhappy over some aspects of U.S. policy toward Syria, Iran and Egypt, but it does not follow that they will therefore seek to detach the kingdom from its longstanding security alliance with the United States. To understand why, it is useful to review the history of the U.S.-Saudi relationship and examine the reality of the security partnership today to evaluate whether Saudi Arabia would really consider recasting its international security ties.

In the seven decades since the United States and Saudi Arabia established military and security links during World War II, there have frequently been policy differences, misunderstandings and angry recriminations, beginning with Saudi anger over U.S. recognition of Israel in 1948. At that time, King Abdul Aziz was under intense pressure from other Arab leaders and from his son, Prince Faisal, to punish the Americans by revoking the Aramco oil concession. Much as he resented what he thought was a breach of promise by Washington, he refrained from taking that dramatic step because, he said, his impoverished country needed the money and technology that only the Americans could provide.

In the ensuing years there have been similar strains, from both sides, over many issues: Saudi Arabia’s ostracism of Anwar Sadat over the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty; Riyadh’s distress over the U.S. invasion of Iraq and over what it perceived as Washington’s unseemly abandonment of Hosni Mubarak, the exclusion of U.S. energy companies from major natural gas exploration contracts; Saudi Arabia’s refusal to do business with the Maliki government in Iraq; the fallout from the 9/11 attacks and Saudi Arabia’s funding of extremist groups; Saudi Arabia’s mediation between Fatah and Hamas; President George W. Bush’s aggressive campaign to export democracy to the Arab world; King Abdullah’s denunciation of what he called an “illegal occupation” of Iraq; and Saudi anxiety about the Obama administration’s announced strategic “pivot” to Asia. None of these has resulted in any open breach or abridgement of the strategic partnership, because the Saudis had nowhere else to go and the Americans were not about to cut them loose. Even the most serious conflict of all, over the Arab oil embargo of 1973-74, lasted just a few months, and after the embargo ended, bilateral U.S.-Saudi relations emerged closer than ever with the creation in 1974 of the U.S.-Saudi Arabia Joint Economic Commission.

Today, the security and defense forces of the United States and Saudi Arabia are deeply entwined, and neither side has any incentive to rupture the partnership. Americans are training and equipping the Saudi National Guard, the Saudi regime’s primary domestic security force, as they have since 1977, and are performing the same functions in the creation of a 35,000-member Facilities Security Force, which is being deployed to protect oil installations, desalination plants, power stations and other critical facilities. Saudi Arabia is in the midst of one of the largest military purchases in history, a $60 billion plus package of aircraft and other equipment, all of it American.

In addition, various U.S. agencies are helping the Saudis to improve security at airports and diplomatic facilities, and protect themselves against cyber-attacks such as the one that knocked out computer networks at Saudi Aramco, the state oil company, last year.

The creation of the Facilities Security Force resulted from a 2006 attempt by al-Qaeda commandos to attack the giant oil processing installation at Abqaiq. That attempt failed, but it exposed multiple security vulnerabilities, compelling the Saudis to recognize they needed help. They sought it from the United States, the only country they would trust with such an endeavor. The United States dispatched a team from the Sandia National Laboratory, in New Mexico, to help the Saudis evaluate and prioritize their security needs. Riyadh was not going to turn to China or Russia for that.

The attempt on Abqaiq “exposed some weaknesses in command and control, and in coordination — and the fact that the [previous] Aramco protective force were not allowed to carry any weapons,” a friend at the Ministry of Petroleum told me last year. “That’s all changed now with American help. A very well trained force is being deployed. But where the Americans really helped was with satellite and cellphone intercept information.” (At least the Saudis appreciate the work of the U.S. National Security Agency, even if many Americans are unhappy about some aspects of it.)

It is true that Saudi Arabia has greatly diversified its trade patterns and is no longer dependent on American firms for its major construction projects. China has been the biggest buyer of Saudi oil since 2009. Chinese contractors built the rail transit system in Mecca, and the Saudis are likely to hire South Korean firms if they go ahead with their plans for nuclear energy. That is a natural evolution as the Saudi economy has modernized and global trade patterns have evolved since the end of the Cold War. It should not be taken as a sign that Saudi Arabia’s royal rulers are planning to jettison the strategic partnership that has ensured their survival in the midst of a regional upheaval.

– Thomas W. Lippman is an adjunct scholar at the Middle East Institute and author of Saudi Arabia on the Edge.

]]>“…my credibility is not on the line. The international community’s credibility is on the line.”

– President Barack Obama, Stockholm, September 4, 2013

President Obama and other US supporters of attacking Syria in response to its alleged use of chemical weapons have based much of their argument on the issue [...]]]>

“…my credibility is not on the line. The international community’s credibility is on the line.”

– President Barack Obama, Stockholm, September 4, 2013

President Obama and other US supporters of attacking Syria in response to its alleged use of chemical weapons have based much of their argument on the issue of credibility. In particular, will other nations (and non-national elements, like terrorist groups) take seriously US declarations if we do not now follow through on preserving Obama’s “red line?”

This question relates to one of the most important elements of statecraft, especially for the United States, which presents itself as the “indispensable nation” and is seen by many others to be so. Further, if the US does not take the lead in trying to reestablish the prohibition on chemical weapons, no one else will do so.

More generally, if the US were seen as being haphazard or even indifferent to the commitments it makes, especially regarding the use of force in specified circumstances, bad results could ensue. Enemies could seek to exploit what they would perceive as American weakness; allies and partners could be less certain that the US would come to their assistance when they were threatened in some way.

This was the conundrum that bedeviled every US administration during the Cold War, as it sought to reassure European allies that the US, even at the price of its own destruction, would use nuclear weapons if the Soviet Union was not, through such US commitment, deterred from aggression against the West.

At this point, with Syria’s violating Mr. Obama’s red line on the use of chemical weapons, reinforced by his declaration last weekend that he will use force, he has no choice but to do so. That will be true even if Congress votes down the authorization he has sought (which it is unlikely to do) and even if he now goes to the United Nations for a mandate to act (which UN Security Council permanent members Russia and China would veto). Obama has “nailed his colors to the mast,” and failing to follow through, it is argued, would have consequences. Contrary to his recent statement in Stockholm, his credibility as president and commander-in-chief is, indeed, “on the line,” certainly in Washington’s unforgiving politics.

But what are those “consequences?” Are all red lines equally significant? Does failure to honor every declared commitment, formal or informal, large or small, always mean that other US commitments will not be taken seriously? It is hard to accept that proposition at face value — and countries which have tested it have rued the day. Indeed, like beauty, credibility is very much “in the eye of the beholder.”

Certainly, some commitments are more important than others. It would not matter if the president promised to quit smoking and did not; but it would matter very much if he pledged to defend the nation against a terrorist attack and sat idly by in face of another 9/11. “Credibility” must thus be seen on a sliding scale, and deciding where on this scale a particular commitment lies is a matter of judgment. (It is also important not to declare a “red line” if it does not truly relate to US national security interests, as Obama did in the current instance.) This is a major reason that most US security commitments take the form of treaties, ratified by the Senate.

The first requirement is to match the commitment to an objective reality of US security needs, as clearly understood both by the US and others. While deterring the use of chemical weapons is desirable and has a long history stemming in particular from World War I, what has happened in Syria does not directly impact on the security of the United States (chemical weapons have also accounted for less than two percent of casualties in the Syrian civil war, to which the “international community” has been largely indifferent). It is not like the attack on Pearl Harbor or 9/11. It is not like Saddam Hussein’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait, which put at risk a large fraction of the world’s exportable hydrocarbons. Had the United States not responded with military force to these direct threats, allies could rightly have wondered about American willpower, and enemies could have tested it elsewhere. Not only would US security have been put in jeopardy, so would the confidence that others have reposed in us. That is not now the case in Syria. Nor, despite the president’s assertion, is this a matter of the international community’s credibility, an effort to spread the responsibility and show the American people that the US is just the agent of a broad consensus. The risk in making that assertion is that a large fraction of the world’s nations do not agree that attacking Syria will help, and that list goes far beyond Russia, China and Iran.

President Obama has made attacking Syria a matter of US credibility. But that can arguably also be less a matter of objective reality, based on cool analysis, than the need to build congressional and popular support for a decision already taken. He can thus raise the stakes to try building political support for a decision he has already made. He knows there is little or no risk of US casualties, given the reliance on stand-off weapons, as was done most recently in the Libya conflict. Given that fact, what objection can there be to making a demonstration of military force, which might encourage “the others” to think twice about using chemical weapons?

The problem lies not in trying to fence off this particularly odious weapon, but in what happens after the US punishes Syria. It is one thing to argue that American credibility is at stake, it is quite another to ignore what has to be a key requirement in establishing that credibility, as well as demonstrating US leadership: laying out a convincing strategy for the Day After. The idea that a limited use of force can teach the Assad regime a lesson without escalating the conflict even further and tipping the balance in favor of the rebels assumes precision in the use of military force that has few if any historical precedents.

And if Assad were toppled, what then? The Syrian civil war pits the Alawite minority rulers against the majority of the population. Assad’s overthrow would likely produce revenge-taking and a bloodbath far worse than what has happened so far, and whoever gains power in Damascus would be unlikely to put US interests high on the agenda.

The Syrian conflict is also part of a larger civil war in the heart of the Middle East that, in its current phase, began with the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq. In getting rid of Saddam Hussein, the US also deposed a minority Sunni government that had ruled over Iraq’s Shia majority for centuries. Since then, several Sunni Arab states (plus Turkey) have sought to right the balance; their efforts to overthrow the Alawites in Syria are just grist to that mill. But the United States certainly has no interest in becoming party to a Sunni-Shia conflict. Quite the reverse: the US and the West need that conflict to end and at least avoid adding fuel to the fire.

In trying to show Congress that the US is not alone in wanting to punish the Syrian government, the administration is underscoring the strong support of Arab states. They want to enlist the United States as their instrument in overthrowing Syria’s Alawite rule and supplement the arms they have been sending the rebels, buttressed by the intervention of Islamist terrorists, many from their own countries — terrorists who see both the Shia and the West (the US in particular) as enemies.

Why then, make such a matter over “credibility” in Syria? To cut to the chase: the real issue of demonstrating US credibility, today, is not about Syria but about Iran. In addition to setting a red line against Syria’s reported use of chemical weapons, President Obama has regularly pledged to keep Iran from getting nuclear weapons with “all options are on the table.” That is far more serious business because nuclear weapons are much more consequential than chemical weapons. Already, Arab states and Israel are arguing that if Obama does not honor his red line commitment in Syria (a relatively minor concern in international security terms), he might not honor his much more important red line regarding an Iranian bomb.

That argument presumes that the US is incapable of weighing the relative importance of different threats or “red lines.” An Iranian bomb could have much greater consequences for US security (though how much is at least debatable) than what is happening in Syria, and whatever the US does in Syria is unlikely to impact its calculations about Iran’s nuclear program.

The false debate over US credibility in Syria is only part of the problem. More important is whether, in the process of trying to reestablish a prohibition against one weapon of warfare, a US attack will cause the Syrian conflict to spread and draw the US more deeply into the Middle East morass. This could also intensify Israel’s concerns about its security, not just regarding Iran, but in particular about potential Islamist terrorism emanating from “liberated” Syria. The US attack will also undercut the ability of Iran’s new president, Hassan Rouhani, to risk engaging the West diplomatically to end the stalemate over its nuclear program. (The administration and Congress have already done their best to throw cold water on possibilities that might emerge from Rouhani’s election.) And that could increase the chances that, at some point, the US will face the terrible dilemma about whether to attack Iran.

Unfortunately, despite assertions to the contrary, the administration has not adequately attempted to resolve the Syrian conflict through diplomacy. Since early on in the Syrian conflict, Obama said that Bashar al-Assad must go and thus ensured that his government would not negotiate. In his first months as Secretary of State, John Kerry should have devoted himself to Syria; instead he pursued Israeli-Palestinian peacemaking, which every experienced negotiator knows can go nowhere while Israel faces real security challenges on at least three fronts (Syria, Iran and Egypt). And Obama is now in Europe, not trying to put together a Syrian peace process, but rather pursuing his domestic political need to convince Congress that we have strong international support for attacking Syria.

The US will attack Syria. But as it does, the Obama administration needs to focus on business far more important for US interests: beginning, finally, to create a viable, integrated, coherent strategy for the Middle East that recognizes all of its many regional facets and has some chance of success, however long it takes and however difficult the task. That plus a full-court press for diplomacy on Syria is where the US should now place its emphasis, not focusing on punishing the Syrian government which, however successful, won’t lead toward peace and security in the region.

This is what it means to be a great power. This is where US credibility abroad is truly at stake.

]]>by Robert E. Hunter

Now, after careful deliberation, I have decided that the United States should take military action against Syrian regime targets. This would not be an open-ended intervention. We would not put boots on the ground. Instead, our action would be designed to be limited in duration and scope.

I’ve [...]]]>

by Robert E. Hunter

Now, after careful deliberation, I have decided that the United States should take military action against Syrian regime targets. This would not be an open-ended intervention. We would not put boots on the ground. Instead, our action would be designed to be limited in duration and scope.

I’ve made a second decision: I will seek authorization for the use of force from the American people’s representatives in Congress….this morning, I spoke with all four congressional leaders, and they’ve agreed to schedule a debate and then a vote as soon as Congress comes back into session.

–President Barack Obama, August 31, 2013

President Barack Obama’s announcement this weekend that he has “decided that the United States should take military action against Syrian regime targets” is remarkable for many reasons, in particular because he coupled it with a commitment to “seek authorization for the use of force from…Congress.”

The first remarkable element is that he has already taken the decision to strike before fully engaging Congress, instead of the usual practice of reserving judgment on possible military action until that process is complete. This immediately begs the question “What if Congress balks?” Does the president go ahead anyway? And if Congress turns him down — after all, he is not “consulting” but “seek[ing] authorization” — does that affect his (and America’s) credibility, as the author of the “red line” against the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian government? Proponents of a military strike are already making that point, although, in this writer’ judgment, it is grossly overdrawn, and no one who wishes us ill should put much weight on this proposition.

The best counterargument is that, at a time when the UN and others are still assembling evidence on the use of chemical weapons (undeniable) and “who did it” (probably the Syrian government), waiting awhile is not a bad thing. Obama covered the point about risk of delay by citing the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff “…that our capacity to execute this mission is not time-sensitive; it will be effective tomorrow, or next week, or one month from now.” Taking the time “to be sure” is thus useful; as is the value in trying to build support in Congress, especially given the clarity of memory about the process leading up to the US-led invasion of Iraq a decade ago, when the intelligence “books” were “cooked” by Bush administration officials, as well as by the British government.

The second remarkable element is that the president did not ask Congress to reconvene in Washington in the next day or two, but is content to wait until members return on September 9th. This provides time for the administration to build its case on Capitol Hill, supporting a decision the president says he has already taken; but it also risks diminishing the perceived sense of importance that his team, notably Secretary of State John Kerry, here and here, has been building about the enormity of what has been done.

A related factor is that the United States will not be responding to a direct assault on the United States or its people abroad, civilian or military, and the case for America’s taking the lead is less about our interests than what, at other times, has been called America’s role as the “indispensable nation.” As has been made clear by all and sundry, if the US does not act, no one else will shoulder the responsibility. But this lack of a direct threat to the nation heightens the president’s need to make his case that the US must take the lead.

The need to make the case to Congress was hammered home by the British parliament’s rejection of a UK role in any attack on Syria, despite the lead taken by Prime Minister David Cameron and Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary William Hague in pressing for military action — and thus helping to “box in” the US president. No doubt, what Parliament did influenced Obama’s decision to get the US Congress firmly on record in supporting his decision to act.

A third remarkable element, though not surprising, is that the administration has apparently given up on the United Nations. To be sure, Russia and China would veto in the Security Council any resolution calling for force; but it would have been common practice — and may yet be done — for the US to apply to the recognized court of world opinion by at least trying, loud and long, to establish an international legal basis for military action, even it fails to achieve UN agreement. There is precedent for this approach, notably over Kosovo in 1998, where the UN failed to act (threat of vetoes), but the US at least made a “college try” and demonstrated the point it sought to make. This made it easier for individual NATO allies to adopt the fudge that each member state could decide for itself the legal basis on which it was prepared to act.

But the most remarkable element of the President’s statement is the likely precedent he is setting in terms of engaging Congress in decisions about the use of force, not just through “consultations,” but in formal authorization. This gets into complex constitutional and legal territory, and will lead many in Congress (and elsewhere) to expect Obama — and his successors — to show such deference to Congress in the future, as, indeed, many members of Congress regularly demand.

But seeking authorization for the use of force from Congress as opposed to conducting consultations has long since become the exception rather than the rule. The last formal congressional declarations of war, called for by Article One of the Constitution, were against Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary on June 4, 1942. Since then, even when Congress has been engaged, it has either been through non-binding resolutions or under the provisions of the War Powers Resolution of November 1973. That congressional effort to regain some lost ground in decisions to send US forces into harm’s way was largely a response to administration actions in the Vietnam War, especially the Tonkin Gulf Resolution of August 1964, which was actually prepared in draft before the triggering incident. The War Powers Resolution does not prevent a president from using force on his own authority, but only imposes post facto requirements for gaining congressional approval or ending US military action. In the current circumstances, military strikes of a few days’ duration, those provisions would almost certainly not come into play.

There were two basic reasons for abandoning the constitutional provision of a formal declaration of war. One was that such a declaration, once turned on, would be hard to turn off, and could lead to a demand for unconditional surrender (as with Germany and Japan in World War II), even when that would not be in the nation’s interests — notably in the Korean War. The more compelling reason for ignoring this requirement was the felt need, during the Cold War, for the president to be able to respond almost instantly to a nuclear attack on the United States or on very short order to a conventional military attack on US and allied forces in Europe.

With the Cold War now on “the ash heap of history,” this second argument should long since have fallen by the wayside, but it has not. Presidents are generally considered to have the power to commit US military forces, subject to the provisions of the War Powers Resolution, which have never been properly tested. But why? Even with the 9/11 attacks on the US homeland, the US did not respond immediately, but took time to build the necessary force and plans to overthrow the Taliban regime in Afghanistan (and, anyway, if President George W. Bush had asked on 9/12 for a declaration of war, he no doubt would have received it from Congress, very likely unanimously).

As times goes by, therefore, what President Obama said on August 29, 2013 could well be remembered less for what it will mean regarding the use of chemical weapons in Syria and more for what it implies for the reestablishment of a process of full deliberation and fully-shared responsibilities with the Congress for decisions of war-peace, as was the historic practice until 1950. This proposition will be much debated, as it should be; but if the president’s declaration does become precedent (as, in this author’s judgment, it should be, except in exceptional circumstances where a prompt military response is indeed in the national interest), he will have done an important and lasting service to the nation, including a potentially significant step in reducing the excessive militarization of US foreign policy.

There would be one added benefit: members of Congress, most of whom know little about the outside world and have not for decades had to take seriously their constitutional responsibilities for declaring war, would be required to become better-informed participants in some of the most consequential decisions the nation has to take, which, not incidentally, also involve risks to the lives of America’s fighting men and women.

Photo Credit: Truthout.org

]]>by Robert E. Hunter

In a surprise move, the British parliament has rejected the Government’s motion to provide support for military action against Syria. This was a clear rebuke to Prime Minister David Cameron and, equally, to the Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary, William Hague, who as much as any leader anywhere pressed [...]]]>

by Robert E. Hunter

In a surprise move, the British parliament has rejected the Government’s motion to provide support for military action against Syria. This was a clear rebuke to Prime Minister David Cameron and, equally, to the Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary, William Hague, who as much as any leader anywhere pressed from early-on for a vigorous response to the alleged use of chemical weapons by the government of Syrian President Bashir al-Assad.The decision by parliament did not spring from nowhere. A good deal of public and elite opinion in Britain remains badly bruised by former Prime Minister Tony Blair’s rampant enthusiasm for the US neo-cons’ drive to invade Iraq ten years ago. In a series of enquiries, Blair was badly tarnished – enquires that were not even contemplated in the United States for members of the administration of President George W. Bush who got so much so wrong. In one of the most telling phrases, the Blair government was accused (with reason) of having concocted a “dodgy dossier” to support claims that Iraq’s Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. While there was nothing quite as telling as US Secretary of State Colin Powell’s presentation to the UN Security Council, which was, in the old British phrase, “economical with the truth,” there were the revelations that intelligence was to be “fixed” around conclusions that the Iraqi WMD did exist. “Fixed,” in this context, meant that the US was determined to go to war, come what may, and the British would go along or, more correctly, would be in the van.

Thus it should not have been that surprising that the lack of clarity in the intelligence picture about the source of the August 21st chemical weapons attacks in Syria led a lot of people in Britain, including in all three major political parties, to express doubts, so much so that the British now have to be ruled out of any military action that the US government might choose to initiate.

Where does this leave President Obama? One senior British leader predicted that the US and perhaps others will go ahead with some form of military action, and they are very likely right. Already, the “commentariat” in Washington has shifted its discussion from the question “whether?” to “when?” and “how?” and has suspended further disbelief about whether this is a good thing.

But not so fast. Questioning does continue on Capitol Hill, on both sides of the aisle, and on several grounds. One could be called the legal niceties – though not so much whether the United Nations would approve of the use of force; its remit has long since gone by the boards for a large fraction of American elected officials, and the Obama administration apparently has already given up on trying to get a UN mandate. The Russians and Chinese would veto any serious resolution in the Security Council – and the British draft tabled this week now can no longer count on the backing of the government that introduced it, a development without precedent in UN history. The idea of going to the General Assembly for an expression of concern about the use of chemical weapons, sufficient for a legal fig-leaf for the Obama administration, is itself a non-starter.

The Capitol Hill legal niceties relate to the role that Congress, or at least a large faction of it, wants to play in any US decision to become engaged actively in hostilities in or over Syria, however limited. This is not so much about the perennial debate over the meaning of the Constitution, which assigns to Congress the sole authority to declare war: that hasn’t been done since December 1941; or even the War Powers Resolution of 1973. It is rather that the average member of Congress, just returning from the so-called “district work period” (AKA holiday), will have had reinforced at least to some degree the rising consensus in the US against yet another war in the Middle East. Iraq is now more or less over; Afghanistan still has a bit of a way to go; and we need to recall that the US, while highly instrumental in forcibly deposing Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddafi two years ago, was content – indeed a bit anxious – to have that characterized as “leading from behind.”

Even more important, perhaps, is not the question of “who struck John?” The administration says that this was the Assad government, even though it has not fallen into the trap of calling it a “slam dunk,” as the hapless Director of the CIA did in 2003 over Iraq’s supposed WMD. Nor is there questioning on Capitol Hill that there could be a “false flag” involved here – that is, someone acting as agent provocateur in order to bring the US to the point of military action against Assad, even at the cost of more lives lost on the rebel side. Important instead is the difficulty that many observers have in understanding what kind of military attack profile can be designed that will do just enough to chasten the Syrian government against a further use of chemical weapons, but not so much that it will risk tipping the balance in the Syrian civil war, dragging the United States deeply into the conflict, and perhaps leading to the overthrow of the Assad regime – to be replaced by what? The answer to that question is not even “blowing in the wind,” but could very well be those whom the US fears most in the Middle East, the Islamist fundamentalists of the worst stripe, who draw their inspiration and support not from the Saudi Arabian and Qatari governments, though, as Sunnis, they very much want Assad to go, but from wealthy individuals in these countries who bankroll the terrorists. The result is the same, and the US and others, notably Israel, fear the potential consequences.

President Obama has already delayed his impending decision to use force, even though it was telegraphed in highly-colored terms by Secretary of State John Kerry (while Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff have been working to slow down the rush to judgment). Now Obama has to face that the ally that was most egging him on, at least within the NATO family, is no longer there; and instead of bolstering the US position has considerably weakened it. The domestic US politics may not have changed – the risk that a Democratic president will be accused of being soft or, heaven forfend, is reluctant to use military force other than to good ends – but the most strident of the public defenders abroad that the evidence and the need for action was incontrovertible has not been able to rally his own commitment to act.

The President is also caught by his own hasty remarks of a couple of years ago, both that the use of chemical weapons in Syria would be a “red line,” and that Assad must go. In neither case did he do anything to back up his remarks – and opponents of deep US military engagement in Syria will not complain about that. In the latter case, however – “Assad must go” – nothing has been worked out politically or diplomatically for Syria’s future that would not, with Assad’s departure, potentially leave the minority Alawites at the brutal mercy of the rebels and especially the “moveable feast” of Sunni terrorists who have now migrated from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Yemen to the richer pickings of Syria. In the haste of some in Washington to get the president to redeem his “redline” pledge as soon as possible, the US even cancelled a meeting with the Russians in the Hague on a possible Geneva II set of peace talks; and it even tried to get the UN secretary general to remove the UN inspectors from Syria – as President George W. Bush did regarding Iraq a decade ago, with consequences that still plague the region and the US reputation there.

Perhaps, therefore, what the British parliament has done is a blessing in disguise. Perhaps it will led the US administration to slow down a bit. This is not so much to let the UN determine formally that chemical weapons were used (that does seem certain) or even whether the perpetrator was the Syrian government (that still is most likely), but finally to begin trying seriously to create some sort of diplomatic framework for Syria’s future (even if, as regrettable as that seems, Assad would have to be part of the picture); and as well to start putting together an overarching strategy for the region as a whole, including analysis, planning, and policy for helping to stem the Sunni-Shia civil war in the heart of the region that was relaunched a decade ago when the US – with Britain that time, and a few others – invaded Iraq.

If “think again” is the result of what the parliament in London did on Thursday, maybe it will be possible finally to set US policy toward the Middle East on a solid, strategically-sound footing. And if that means the President has to change his mind regarding the likelihood of military attack, so be it; it would be consonant with his totally-correct statement last week that he is paid by the American people to promote US interests. And if he gets to policies that can do that, by however circuitous a route, that is a good thing.

by Peter Jenkins

For the last week the British government has given every sign of being in a dreadful muddle over how to react to the suspicion that chemical weapons (CW) were used in the suburbs of Damascus early on 21 August.

Two words that ought to have featured prominently in ministerial [...]]]>

by Peter Jenkins

For the last week the British government has given every sign of being in a dreadful muddle over how to react to the suspicion that chemical weapons (CW) were used in the suburbs of Damascus early on 21 August.

Two words that ought to have featured prominently in ministerial statements, “due process”, were entirely absent. Instead, Messrs William Hague and James Cameron spoke at times as though the UK and its Western allies were fully entitled to act as judge, jury and executioner.

I hope I won’t offend US readers if I say that Europeans half expect that sort of mentality from US leaders. We look on the US as a country in which habits formed in the Wild West in the nineteenth century resurface from time to time. But from our own European politicians, schooled by centuries of intra-European conflict, we look for more measured and cautious responses.

Reinforcing the impression of indifference to international legality, British ministers seemed hopelessly confused about how the precipitate use of force that they were advocating could be justified, and about what it was supposed to achieve.

At one moment President Bashar al-Assad had to be “punished”; at another the West had to “retaliate” for his use of CW (although so far Western nationals are not reported to be among the victims).

Some statements suggested that the West should act to uphold an international norm against the use of CW, others that the West had to act in order to protect Syria’s population from further CW attacks (although none of the military measures reportedly under consideration can come close to delivering “protection”).

Mercifully, as of 29 August, it looks as though Messrs Hague and Cameron are at last starting to come to their senses, sobered perhaps by parliamentary resistance to signing a blank cheque for a resort to force and by opinion polls suggesting that the British public is opposed to force by a margin of more than two to one.

To those of us who are familiar with the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) this pantomime has been puzzling.

Syria is one of (only) seven states that have not ratified the CWC. The rational way to proceed, however, is to treat Syria, mutatis mutandis, as though it were a CWC party, since the norm enshrined in the CWC dates back to 1925 and is, effectively, a global norm, a norm that no state can reasonably reject (unlike the so-called “right to protect”, propagated by Mr. Blair and others, which is far from being universally accepted).

The relevant provisions of the CWC can be summarised as follows:

- CWC parties are entitled to request “challenge inspections” to clarify possible instances of non-compliance with the Convention’s prohibitions, and to have this inspection conducted “without delay”;

- The inspection team will produce a report which contains factual findings as well as an assessment of the cooperation extended by the inspected party;

- The inspected party has a right to comment on that report and to have its comments submitted to other parties;

- The parties shall then meet to decide whether non-compliance has occurred, and whether further action may be necessary “to redress the situation and to ensure compliance”.

Note the emphasis on giving the inspected party a right to comment before parties come to conclusions about what the inspection report implies. This could be especially important in the Syrian case if, as leaked signal intelligence implies, a Syrian army unit used CW last week against the wishes of the Syrian Ministry of Defence.

Note, too, the emphasis on redressing the situation. What matters in Syria now, if the UN inspectors report that government CW were used last week, is that the government take steps to ensure that this never happens again. Ideally, the UN Security Council (acting, so to speak, on behalf of CWC parties in this instance) can persuade the Syrian government to adhere to the CWC and destroy its CW stocks under international supervision. There will be no resistance to that outcome from Russia, Iran or China, all fervent supporters of the CWC.

Note, finally, the absence of any reference in the CWC to the “punishing” of non-compliance. That is consistent with a view that it is inappropriate for sovereign states to treat one another like common criminals (a view to which the West eagerly subscribes when the non-compliant state is Israel). Of course, if the Syrian government wishes to punish the commander(s) of any unit(s) found to have been responsible for last week’s outrage, this is another matter.

By giving priority to “due process” and “redressing the situation” Western leaders have an opportunity to set a good precedent for the handling of future challenges to global norms.

]]>

by Mitchell Plitnick

Russia is not staying silent as the US appears to be positioning itself for an attack on the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria. Defending its last key ally in the region, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov warned the West against intervention. Western nations [...]]]>

by Mitchell Plitnick

Russia is not staying silent as the US appears to be positioning itself for an attack on the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria. Defending its last key ally in the region, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov warned the West against intervention. Western nations should avoid repeating “past mistakes,” said Lavrov.

More importantly, Lavrov illustrates just how broken and vaporous the system of “international law” is when it comes to conflict and protecting civilians. “The use of force without the approval of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is a very grave violation of international law,” he said. And there is no question that he is correct.

An intervention in Syria requires the approval of the Security Council in order to be comply with international law. Such authorizations are, quite naturally, exceedingly rare. Not only does it require a majority vote in the Council, but, more importantly, all five permanent members of the Council (the US, Russia, China, Great Britain and France) must also agree. Any one of those countries can exercise its right to veto any resolution before the Council.

The idea, in 1945, made some sense. In the post-World War II era, there was still some question as to whether the US and USSR would perhaps build on their wartime alliance and find a way to work together, but it seemed unlikely. An incentive to maintain some sense of order in the world by working together on such matters and being able to block one-sided moves might have seemed sensible. It’s even worked out that way from time to time. But for the most part, it’s been a recipe for paralysis and a means to prevent action on matters of global concern, rather than to promote it.

The most obvious example of this is the matter on which there has been, by far, more Security Council vetoes than any other: Israel’s occupation of territories captured in the 1967 war. From 1946-1971, the USSR was the overwhelming leader in Security Council vetoes; no other country was even close. These were, of course, mostly Cold War-related resolutions that directly or indirectly took aim at Soviet actions and policies in various parts of the world. Since then, the overwhelming leader has been the United States, with the clear majority of those vetoes being made on behalf of Israel, protecting its occupation and concomitant violence and settlement expansion.

Indeed, in recent years, the problem has gotten so bad that most resolutions regarding Israel-Palestine have been withdrawn in advance, knowing the US will veto as a matter of course. The matter reached its ultimate absurdity in 2011, when the Obama administration vetoed a UNSC resolution that stated nothing at all that was not already official US policy. But the veto was expected and required. The fact that it was such a moderate resolution raised fears among AIPAC and its various fellow travellers in the Israel lobby, and there was a lot of public pressure on Obama to veto. But there’s no reason to think he wouldn’t have done so anyway.

Politics and power, not international law, govern international matters. The fact is that legality will have no bearing on the US decision to attack Syria or refrain from taking action. The decision will be based on strategy and politics.

The system of international law is irreparably broken. Ultimately, any system of law depends entirely on the ability of the judicial body to enact penalties and sanctions on lawbreakers. Such penalties don’t exist for the United States, nor for Russia or China or the other members of the Security Council. Britain and France are more compliant with international law than the others, but this is due not to fear of censure but because their own situations (including widespread European support for abiding by international law, as well as the experience of the two World Wars and the end of colonialism, the latter having removed a lot of European disincentives toward international law) push them in that direction.

Indeed, it is worth asking this question: if one believes that intervention in Syria is needed to stop what is already a humanitarian disaster from getting much worse, should international law be ignored in doing so? It seems inescapable that the answer to that question is yes, and one is then left with only the question of whether military intervention will help or hurt the millions of Syrians in the crossfire.

But at what point can we claim with reasonable certainty that the moral imperative trumps the law? Particularly in a hypothetical world where the law actually matters, where should that line be drawn? In point of fact, few people are so naïve as to believe that military intervention ever occurs for purely humanitarian reasons. It is generally done in order to pursue the invading country’s interests, and if some humanitarian good is done on the way, well that is just fine. And most of the time, the humanitarian interests are only a cover for other goals; the situation is often oversimplified so the public will support the intervention, which is sometimes vastly distorted.

In this instance, it is Russia warning the United States against violating international law, but the US has played the same game on many occasions — the 2003 push for a UN imprimatur for the invasion of Iraq being perhaps the most prominent and revolting instance.

The alternative to a world governed by international law is a world where might makes right. That is, indeed, the world in which we live. The point here is not that international law should be done away with. On the contrary, it must be strengthened exponentially. A legal system that can enjoy at least some insulation from the whims of politics, both domestic and international, is crucial, and the International Criminal Court and International Court of Justice have at least some of that. But more importantly, there must be a mechanism where even the most powerful country can be held accountable for violating the law.

Such a system will never be perfect, of course. Even in the realm of domestic law, we regularly see differences in how it is applied and defied by the rich and the poor. But even the wealthiest individuals have to at least consider their actions when breaking the law. Some system where powerful actors are treated the same as everyone else must be put into place. The answer to how that can be achieved is for better minds than mine, but asking the question is the first step.

Other aspects need revision or at least revisiting as well. Sovereignty is a crucial principle, without a doubt, but it is also used by tyrants to shield themselves from, for example, reprisals under international human rights law. The debate over intervening in Syria following alleged chemical weapons use by the Syrian government is inherently related to the current system of international law, which is broken far beyond the point of having any effectiveness. In many ways, it is an obstacle. It needs to be rebuilt, before more Syrias confront us.

]]>