By Scott McConnell

I spent the weekend canvassing for Obama in the Virginia Beach area. The task for the hundreds of volunteers who descended from DC and New York was to make sure the maximum number of Virginia’s “sporadic Democratic voters” — a designation which seemed to mean, pretty much, [...]]]>

By Scott McConnell

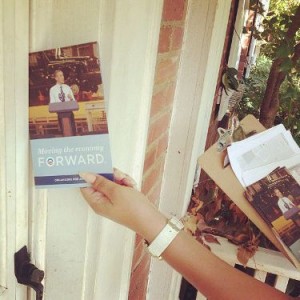

I spent the weekend canvassing for Obama in the Virginia Beach area. The task for the hundreds of volunteers who descended from DC and New York was to make sure the maximum number of Virginia’s “sporadic Democratic voters” — a designation which seemed to mean, pretty much, poor minorities — get to the polls on Tuesday. People needed to know where their polling place was, what ID they needed, be reminded that it’s important and make a foolproof plan to vote. And, of course shooting down the various disinfomational memes that “someone” has been circulating in the area: that “because of the hurricane” you can vote by calling this number, or that you can’t vote a straight Democratic ticket — if you do, your Senate or Congress vote won’t count.

I spent the weekend canvassing for Obama in the Virginia Beach area. The task for the hundreds of volunteers who descended from DC and New York was to make sure the maximum number of Virginia’s “sporadic Democratic voters” — a designation which seemed to mean, pretty much, poor minorities — get to the polls on Tuesday. People needed to know where their polling place was, what ID they needed, be reminded that it’s important and make a foolproof plan to vote. And, of course shooting down the various disinfomational memes that “someone” has been circulating in the area: that “because of the hurricane” you can vote by calling this number, or that you can’t vote a straight Democratic ticket — if you do, your Senate or Congress vote won’t count.

It is a core axiom among Democratic activists that the essence of the Republican “ground game” is to suppress the Democratic votes with lies, intimidation and whatever might work.

It was a curiously moving experience. Much of the sentiment comes from simple exposure. I have led most of my life not caring very much whether the poor voted, and indeed have sometimes been aware my interests aligned with them not voting at all. But that has changed. And so one knocks on one door after another in tiny houses and apartments in Chesapeake and Newport News, some of them nicely kept and clearly striving to make the best of a modest lot, others as close to the developing world as one gets in America. And at moments one feels a kind of calling — and then laughs at the Alinskian presumption of it all. Yes, we are all connected.

At times when I might have been afraid — knocking on a door of what might of well have been a sort of crack house — I felt no fear. I was protected by age and my Obama campaign informational doorhangers.

And occasionally, one strikes canvassing gold. In one decrepit garden apartment complex, where families lived in dwellings the size of maybe two large cars, a young man (registered) came around behind me while I was talking to his mother. “Yeah” he said, “Romney wins, I’m moving back to the islands. He’s gonna start a war, to get the economy going.” Really. He stopped to show me a video on his smart phone, of one of his best friends, a white guy in the Marines. I couldn’t make out what the video was saying, but I took it as a Monthly Review moment. In a good way.

And Tomiko. Plump, pretty, dressed in a New York Jets jersey and sweatpants. “If the campaign can get me a van, I can get dozens of people around here to the polls on Tuesday.” Yes, Tomiko, the campaign might be able to do that, and someone will be calling you.

A very small sample size, but of the white female Obama volunteers with whom I had long conversations, one hundred percent had close relatives who had failed marriages with Mormon men. I think Mormonism is the great undiscussed subject of the campaign, and I don’t quite know what to make of it myself. But contrary to Kennedy’s Catholicism (much agonized over) and Obama’s Jeremiah Wright ties (ditto), Mormonism is obviously the central driving factor of Romney’s life. This may be a good thing or a bad thing — but it is rather odd that it is not discussed, at all. I think it’s safe to say that if Romney wins, the Church of Latter Day Saints will come under very intense scrutiny, and those of us who have thought of the church as simply a Mountain West variation on Protestantism will be very much surprised.

I spent a good deal of time driving and sharing meals with three fellow volunteers, professional women maybe in their early forties, two black, one white, all gentile, all connected in some way, as staffers or lobbyists, to the Democratic Party. All had held staff positions at the Democratic convention. They had scoped out my biography, knew the rough outlines from neocon, to Buchananite, to whatever I am now. They knew my principal reason for supporting Obama was foreign policy, especially Iran. They spent many hours interrogating me about my reactionary attitudes on women, race, immigration, all in good comradely fun of course. At supper last night before we drove back to DC, I asked them (all former convention staffers) what they thought about the contested platform amendment on Jerusalem. Silence. Finally one of them said, with uncharacteristic tentativeness, “Well, I’m not sure I really know enough about that issue.” More silence.

Then I told them I thought it was a historic moment, (though I refrained from the Rosa Parks analogy I have deployed before) which portended a sea change in Democratic Party attitudes on the question. I cited various neocon enforcers who feared the same thing.

And now, with permission to speak freely, they spoke up. It came pouring out. Yes, obviously Israel has to give up something. There has to be a two-state solution. We can’t just one-sidedly support Israel, and so on. But really striking was their reluctance, perhaps even fear, to voice their own opinions before hearing mine.

– Scott McConnell is a founding editor of The American Conservative.

]]>Dispensing with some of the neo-conservative rhetoric he has used in the past, [...]]]>

In what was billed as a major foreign policy address, Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney Monday assailed Barack Obama for “passivity” in the conduct of U.S. foreign policy, arguing that it was “time to change course” in the Middle East, in particular.

In what was billed as a major foreign policy address, Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney Monday assailed Barack Obama for “passivity” in the conduct of U.S. foreign policy, arguing that it was “time to change course” in the Middle East, in particular.

Dispensing with some of the neo-conservative rhetoric he has used in the past, he nonetheless argued that the “risk of conflict in the region is higher now than when (Obama) took office” and that Washington should tie itself ever more closely to Israel.

“I will re-affirm our historic ties to Israel and our abiding commitment to its security – the world must never see any daylight between our two nations,” he told cadets at the Virginia Military Institute, adding that Washington must “also make clear to Iran through actions – not just words – that their (sic) nuclear pursuit will not be tolerated.”

As he has in the past, he also called for building up the U.S. Navy, pressing Washington’s NATO allies to increase their military budgets in the face of a Vladimir Putin-led Russia, and ensuring that Syrian rebels “who share our values …obtain the arms they need to defeat (President Bashar Al-) Assad’s tanks, helicopters, and fighter jets.”

Independent analysts described the speech as an effort to move to the centre on foreign-policy issues, much as he did on economic issues during his debate with Obama last week. As a result, they said, his specific policy prescriptions did not differ much, if at all, from those pursued by the current administration.

“In a speech where he attempted to be more centrist, he ended up articulating positions that sound like those of Obama,” noted Charles Kupchan, a foreign-policy expert at the Council on Foreign Relations who teaches at Georgetown University.

Indeed, in both tone and policy, the speech marked a compromise between his neo-conservative and aggressive nationalist advisers on the one hand, and his more-realist aides on the other.

Absent from the speech altogether, for example, was any reference to making the 21st century “an American Century”, a neo-conservative mantra since the mid-1990s that Romney used repeatedly in his one major foreign-policy address during the Republican primary campaign almost exactly one year ago.

The latest speech comes at a critical moment in the presidential campaign. While Romney was lagging badly in the polls in late September, his strong performance in last week’s debate against a surprisingly listless Obama last week has revived his prospects.

While Obama had been leading by about four percentage points nationwide before the debate, the margin has since fallen to only two percentage points, while on-line bettors at the intrade website have lowered the chances of an Obama’s victory from nearly 80 percent to 64 percent.

Obama’s seeming passivity during the debate may have played a role in the Romney campaign’s decision to deliver a foreign-policy address if for no other reason than that it highlighted the argument that many Republican foreign-policy critics, especially the neo-conservatives, have been building over the past year: that the president’s policies in the Middle East, in particular, have been too passive, and that “leading from behind” – a phrase used by an anonymous White House official quoted in “The New Yorker” magazine 18 months ago to describe Obama’s low-profile but critical support for the rebellion against Libyan leader Moammar Qadhafi – was unacceptable amid what Romney described Monday as the world’s “longing for American leadership”.

Indeed, in the wake of last month’s siege of the U.S. embassy in Cairo and the killing of the U.S. ambassador and three other embassy staffers in Benghazi, Romney’s vice presidential running-mate, Rep. Paul Ryan, and other surrogates have tried to link recent displays of anti-U.S. sentiment and Islamic militancy in the region to disasters, notably the seizure of the U.S. embassy in Tehran, that plagued – and perhaps ultimately doomed – former President Jimmy Carter’s re-election bid in 1980.

While Romney did not refer to that period, he argued that last month’s violence in the Middle East demonstrated “how the threats we face have grown so much worse” as the “struggle between liberty and tyranny, justice and oppression, hope and despair” in the region has intensified. “And the fault lines of this struggle can be seen clearly in Benghazi itself.”

Recalling the U.S. response to a similar struggle in Europe after World War II and invoking then-Secretary of State George Marshall (without, however, referring to the Marshall Plan that poured U.S. aid and investment into Western Europe), Romney argued that Washington should lead now as it did then.

“Unfortunately, this president’s policies have not been equal to our best examples of world leadership,” he said, adding, “…it is the responsibility of our president to use America’s great power to shape history – not to lead from behind, leaving our destiny at the mercy of events.

“Unfortunately, that is exactly where we find ourselves in the Middle East under President Obama,” he said. “…We cannot support our friends and defeat our enemies in the Middle East when our words are not backed up by deeds, …and the perception of our strategy is not one of partnership, but of passivity.

“It is clear that the risk of conflict in the region is higher now than when the President took office,” he claimed, citing the killings in Benghazi, the Syrian civil war, “violent extremists on the march,” and tensions surrounding Iran’s nuclear programme.

On specific policy recommendations, however, Romney failed to substantially distinguish his own from Obama’s. Indeed, in contrast to recently disclosed off-the-record remarks to funders in which he indicated that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was likely unresolvable, he said he would “recommit” the U.S. to the creation of a “democratic, prosperous Palestinian state”, arguing that “only a new president” can make that possible.

On Egypt, he promised to condition aid to the government on democratic reform and maintaining the peace treaty with Israel; on Libya, he said he would pursue those responsible for the murders of U.S. diplomats.

On Iran, he promised to impose new sanctions and tighten existing ones, as well as build up U.S. military forces in the Gulf; on Afghanistan, he said he would weigh the advice of his military commanders on the pace of withdrawal before the end of 2014.

On Syria, he promised to work with Washington’s partners to “identify and organise” opposition elements that “share our values” and ensure they get the weapons needed to defeat Assad. In each case, he suggested that Obama’s policies were less forceful but did not explain how.

“On matters from Syria to Afghanistan to sanctions on Iran, the speech is essentially a description of current U.S. policies,” said Paul Pillar, a former top CIA Middle East analyst now at Georgetown University. “One struggles to discern how a Romney policy would work differently.”

]]>By John Feffer

via Tom Dispatch

Barack Obama is a smart guy. So why has he spent the last four years executing such a dumb foreign policy? True, his reliance on “smart power” — a euphemism for giving the Pentagon a stake in all [...]]]>

By John Feffer

via Tom Dispatch

Barack Obama is a smart guy. So why has he spent the last four years executing such a dumb foreign policy? True, his reliance on “smart power” — a euphemism for giving the Pentagon a stake in all things global — has been a smart move politically at home. It has largely prevented the Republicans from playing the national security card in this election year. But “smart power” has been a disaster for the world at large and, ultimately, for the United States itself.

Power was not always Obama’s strong suit. When he ran for president in 2008, he appeared to friend and foe alike as Mr. Softy. He wanted out of the war in Iraq. He was no fan of nuclear weapons. He favored carrots over sticks when approaching America’s adversaries.

His opponent in the Democratic primaries, Hillary Clinton, tried to turn this hesitation to use hard power into a sign of a man too inexperienced to be entrusted with the presidency. In 2007, when Obama offered to meet without preconditions with the leaders of Cuba, North Korea, and Iran, Clinton fired back that such a policy was “irresponsible and frankly naïve.” In February 2008, she went further with a TV ad that asked voters who should answer the White House phone at 3 a.m. Obama, she implied, lacked the requisite body parts — muscle, backbone, cojones– to make the hard presidential decisions in a crisis.

Obama didn’t take the bait. “When that call gets answered, shouldn’t the president be the one — the only one — who had judgment and courage to oppose the Iraq war from the start,” his response ad intoned. “Who understood the real threat to America was al-Qaeda, in Afghanistan, not Iraq. Who led the effort to secure loose nuclear weapons around the globe.”

Like most successful politicians, Barack Obama could be all things to all people. His opposition to the Iraq War made him the darling of the peace movement. But he was no peace candidate, for he always promised, as in his response to that phone call ad, to shift U.S. military power toward the “right war” in Afghanistan. As president, he quickly and effectively drove a stake through the heart of Mr. Softy with his pro-military, pro-war speech at, of all places, the ceremony awarding him the Nobel Peace Prize.

Obama’s protean abilities have come to the fore in his approach to what once was called “soft power,” a term Harvard professor Joseph Nye coined in his 1990 book Bound to Lead. For more than 20 years, Nye has been urging U.S. policymakers to find different ways of leading the world, exercising what he termed “power with others as much as power over others.”

After 9/11, when “soft” became an increasingly suspect word, Washington policymakers began to use “smart power” to denote a menu of expanded options that were to combine the capabilities of both the State Department and the Pentagon. “We must use what has been called ‘smart power,’ the full range of tools at our disposal — diplomatic, economic, military, political, legal, and cultural — picking the right tool, or combination of tools, for each situation,” Hillary Clinton said at her confirmation hearing for her new role as secretary of state. “With smart power, diplomacy will be the vanguard of foreign policy.”

But diplomacy has not been at the vanguard of Obama’s foreign policy. From drone attacks in Pakistan and cyber-warfare against Iran to the vaunted “Pacific pivot” and the expansion of U.S. military intervention in Africa, the Obama administration has let the Pentagon and the CIA call the shots. The president’s foreign policy has certainly been “smart” from a domestic political point of view. With the ordering of the Seal Team Six raid into Pakistan that led to the assassination of Osama bin Laden and “leading from behind” in the Libya intervention, the president has effectively removed foreign policy as a Republican talking point. He has left the hawks of the other party with very little room for maneuver.

But in its actual effects overseas, his version of “smart power” has been anything but smart. It has maintained imperial overstretch at self-destructive expense, infuriated strategic competitors like China, hardened the position of adversaries like Iran and North Korea, and tried the patience of even long-time allies in Europe and Asia.

Only one thing makes Obama’s policy look geopolitically smart — and that’s Mitt Romney’s prospective foreign policy. On global issues, then, the November elections will offer voters a particularly unpalatable choice: between a Democratic militarist and an even more over-the-top militaristic Republican, between Bush Lite all over again and Bush heavy, between dumb and dumber.

Mr. Softy Goes to Washington

Mr. Softy went to Washington in 2008 and discovered a backbone. That, at least, is how many foreign policy analysts described the “maturation” process of the new president. “Barack Obama is a soft power president,” wrote theFinancial Times’s Gideon Rachman in 2009. “But the world keeps asking him hard power questions.”

According to this scenario, Obama made quiet overtures to North Korea, and Pyongyang responded by testing a nuclear weapon. The president went to Cairo and made an impressive speech in which he said, among other things, “we also know that military power alone is not going to solve the problems in Afghanistan and Pakistan.” But individuals and movements in the Muslim world — al-Qaeda, the Taliban — continued to challenge American power. The president made a bold move to throw his support behind nuclear abolition, but the nuclear lobby in the United States forced him to commit huge sums to modernizing the very nuclear complex he promised to negotiate out of existence.

According to this scenario, Obama came to Washington with a fistful of carrots to coax the world, nonviolently, in the direction of peace and justice. The world was not cooperative, and so, in practice, those carrots began to function more like orange-colored sticks.

This view of Obama is fundamentally mistaken. Mr. Softy was a straw man created from the dreams of his dovish supporters and the nightmares of his hawkish opponents. That Obama avatar was useful during the primary and the general election campaign to appeal to a nation weary of eight years of cowboy globalism. Like a campaign advisor ill-suited to the bruising policy world of Washington, Mr. Softy didn’t survive the transition.

This view of Obama is fundamentally mistaken. Mr. Softy was a straw man created from the dreams of his dovish supporters and the nightmares of his hawkish opponents. That Obama avatar was useful during the primary and the general election campaign to appeal to a nation weary of eight years of cowboy globalism. Like a campaign advisor ill-suited to the bruising policy world of Washington, Mr. Softy didn’t survive the transition.

Consider, for example, Obama’s speech in Cairo in June 2009. This inspiring speech should have signaled a profound shift in U.S. policy toward the Muslim world. But what Obama didn’t mention in his speech was his earlier conversation with outgoing president George W. Bush in which he’d secretlyagreed to continue two major Bush initiatives: the CIA’s unmanned drone air war in Pakistan’s tribal borderlands and the covert program to disrupt Iran’s nuclear program with computer viruses.

Obama didn’t just continue these programs; he amplified them. The result has been an unprecedented expansion of U.S. military power through unmanned drones in Pakistan and neighboring Afghanistan as well as Somalia and Yemen. The use of drones, and the civilian casualties they’ve caused, has in turn enflamed public opinion around the world, with the favorability rating of the United States under Obama in majority Muslim countries falling to a new low of 15% in 2012, lower, that is, than the rock-bottom standard set by the Bush administration.

The drone campaign has undermined other smart power approaches, including that old standby diplomacy, not only by antagonizing potential interlocutors but also by killing a good number of them. Along with the raid that killed Osama bin Laden, often cited as one of Obama’s signal accomplishments, the drone war has by now provoked a slow-motion rupture in relations between Washington and Islamabad.

The covert cyber-war initiative against Iran’s nuclear program, conducted with Israeli cooperation, produced both the Stuxnet worm, which wreaked havoc on Iranian centrifuges, and the Flame virus, which monitored its computer network. Instead of vigorously pursuing diplomatic solutions — such as the nuclear compromise that Brazil and Turkey cobbled together in 2010 that might have defused the situation and guaranteed a world without an Iranian bomb — the Obama administration acted secretly and aggressively. If the United States had been the target of such a cyber attack, Washington would have considered it an act of war. Meanwhile, the United States has set a dangerous precedent for future attacks in this newest theater of operations and unleashed a weapon that could even be reverse-engineered and sent back in our direction.

Nor was diplomacy ever actually on the table with North Korea. The Obama team came in with a less than half-hearted commitment to the Six Party process — the negotiations to address North Korea’s nuclear program among the United States, China, Russia, Japan, and the two Koreas, which had stalled in the final months of George W. Bush’s second term. In the National Security Council, Asia point man Jeffrey Bader axed a State Department cable that would have reassured the North Koreans that a U.S. policy of engagement would continue. “Strategic patience” became the euphemism for doing nothing and letting hawkish leaders in Tokyo and Seoul unravel the previous years of engagement. After some predictably belligerent rhetoric from Pyongyang, followed by a failed missile launch and a second nuclear test, Obama largely dispensed with diplomacy altogether.

Hillary Clinton did indeed move quickly to increase the size of the State Department budget to hire more people and implement more programs to beef up diplomacy. That budget grew by more than 7% in 2009-2010. But that didn’t bring the department of diplomacy up to even $50 billion. In fact, it is still plagued by a serious shortage of diplomats and, as State Department whistleblower Peter van Buren has written, “The whole of the Foreign Service is smaller than the complement aboard one aircraft carrier.” Meanwhile, despite a persistent recession, the Pentagon budget continued to rise during the Obama years — a roughly 3% increase in 2010 to about $700 billion. (And Mitt Romney promises to hike it even more drastically.)

Like most Democratic politicians, Obama has been acutely aware that hard power is a way of establishing political invulnerability in the face of Republican attacks. But the use of hard power to gain political points at home is a risky affair. It is the nature of this “dumb power” to make the United States into a bigger target, alienate allies, and jeopardize authentic efforts at multilateralism.

A Kinder, Gentler Empire

Despite its rhetorical flexibility, “smart power” has several inherent flaws. First, it focuses on the means of exercising power without questioning the ends toward which power is deployed. The State Department and the Pentagon will tussle over which agency can more effectively win the hearts and minds of Afghans. But neither agency is willing to rethink the U.S. presence in the country or acknowledge how few hearts and minds have been won.

As with Afghanistan, so with the rest of the world. For all his talk of power “with” rather than “over,” Joseph Nye has largely been concerned with different methods by which the United States can maintain dominion. “Smart power” is not about the inherent value of diplomacy, the virtues of collective decision-making, or the imperatives of peace, justice, or environmental sustainability. Rather it is a way of calculating how best to get others to do what America wants them to do, with the threat of a drone strike or a Special Forces incursion always present in the background.

The Pentagon, at least, has been clear about this point. In 2007, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates argued for “strengthening our capacity to use soft power and for better integrating it with hard power.” The Pentagon has long realized that a toolbox with only a single hammer in it handicaps the handyman, but it still persists in seeing a world full of nails.

At a more practical level, “smart power” encounters problems because in this “integration,” the Pentagon always turns out to be the primary partner. As a result, the work of diplomats, dispensers of humanitarian aid, and all the other “do-gooders” who attempt to distinguish their work from soldiers is compromised. After decades of trying to persuade their overseas partners that they are not simply civilian adjuncts to the Pentagon, the staff of the State Department has now jumped into bed with the military. They might as well put big bull’s eyes on their backs, and there’s nothing smart about that.

“Smart power” also provides a lifeline for a military that might face significant cuts if Congress’s sequestration plan goes through. NATO has already shown the way. Its embrace of “smart defense” is a direct response to military cutbacks by European governments. The Pentagon is deeply worried that budget-cutters will follow the European example, so it is doing what corporations everywhere attempt during a crisis. It is trying to rebrand its services.

Always in search of a mission, the Pentagon now has its fingers in just about every pie in the bakery. The Marines are doing drug interdiction in Guatemala. Special Operations forces are constructing cyclone shelters in Bangladesh. The U.S. Navy provided post-disaster relief in Japan after the Fukushima nuclear meltdown, while the U.S. Army did the same in Haiti. In 2011, the Africa Command budgeted $150 million for development and health care.

The Pentagon, in other words, has turned itself into an all-purpose agency, even attempting “reconstruction” along with State and various crony corporations in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is preparing for the impact of climate change, pouring R & D dollars into alternative energy, and running operations in cyberspace. The Pentagon has been smart about its power by spreading it everywhere.

Dumb vs. Dumber

As president, Obama has shown no hesitation to use force. But his use of military power has not proven any “smarter” than that of his predecessor. Iran and North Korea pushed ahead with their nuclear programs when diplomatic alternatives were not forthcoming. Nuclear power Pakistan is closer to outright anarchy than four years ago. Afghanistan is a mess, and an arms race is heating up in East Asia, fueled in part by the efforts of the United States and its allies to box in China with more air and sea power.

In one way, however, Obama has been Mr. Softy. He has shown no backbone whatsoever in confronting the bullies already in America’s corner. He has done little to push back against Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his occupation policies. He hasn’t confronted Saudi Arabia, the most autocratic of U.S. allies. In fact, he has leveraged the power of both countries — toward Iran, Syria, Bahrain. A key component of “smart power” is outsourcing the messy stuff to others.

Make no mistake: Mitt Romney is worse. A Romney-Ryan administration would be a step backward to the policies of the early Bush years. President Romney would increase military spending, restart a cold war with Russia, possibly undertake a hot war against Iran, deep-six as many multilateral agreements as he could, and generally resurrect the Ugly American policies of the recent past.

But President Romney wouldn’t fundamentally alter U.S. foreign policy. After all, President Obama has largely preserved the post-9/11 fundamentals laid down by George W. Bush, which in turn drew heavily on a unilateralist and militarist recipe that top chefs from Bill Clinton on back merely tweaked.

Obama has mentioned, sotto voce, that Mr. Softy might resurface if the incumbent is reelected. Off mic, as he mentioned in an aside to Russian President Dmitry Medvedev at a meeting in Seoul last spring, he has promised to show more “flexibility” in his second term. This might translate into more arms agreements with Russia, more diplomatic overtures like the effort with Burma, and more spending of political capital to address global warming, non-proliferation, global poverty, and health pandemics.

But don’t count on it. The smart money is not with Obama’s smart power. Mr. Softy has largely been an electoral ploy. If he’s re-elected, Obama will undoubtedly continue to act as Mr. Stick. Brace yourself for four more years of dumb power — or, if he loses, even dumber power.

John Feffer, a TomDispatch regular, is an Open Society Fellow for 2012-13 focusing on Eastern Europe. He is the author of Crusade 2.0: The West’s Resurgent War on Islam (City Lights Books). His writings can be found on his website johnfeffer.com. To listen to Timothy MacBain’s latest Tomcast audio interview in which John Feffer discusses power — hard, soft, smart, and dumb — click here or download it to your iPod here.

Copyright 2012 John Feffer

]]>