by Jim Lobe

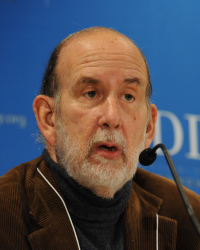

Exactly three weeks ago, a confident Dennis Ross, President Barack Obama’s top Iran policy-maker for most of his first term, made the following assessments and predictions in an op-ed entitled, ironically, “Don’t Discount the Iranian Election:”

So now Ayatollah Khamenei has decided not to leave anything [...]]]>

by Jim Lobe

Exactly three weeks ago, a confident Dennis Ross, President Barack Obama’s top Iran policy-maker for most of his first term, made the following assessments and predictions in an op-ed entitled, ironically, “Don’t Discount the Iranian Election:”

So now Ayatollah Khamenei has decided not to leave anything to chance. …If there had been any hope that Iran’s presidential election might offer a pathway to different policy approaches on dealing with the United States, he has now made it clear that will not be the case. His action should be seen for what it is: a desire to prevent greater liberalization internally and accommodation externally.”

…Clearly, the Supreme Leader wanted to avoid the kind of excitement that Rafsanjani would have stirred up had he continued making public statements, as he has over the last two years, about Iran’s need to fix the economy and reduce Iran’s isolation internationally (a theme he has emphasized in recent years). But the exclusion of Rafsanjani from the election is also an important signal to anyone concerned about Iran’s nuclear program. If the Supreme Leader had been interested in doing a deal with the West on the Iranian nuclear program, he would have wanted [former President Akbar Hashemi] Rafsanjani to be president.

I say that …because if the Supreme Leader were interested in an agreement, he would probably want to create an image of broad acceptability of it in advance. Rather than having only his fingerprints on it, he would want to widen the circle of decision-making to share the responsibility. And he would set the stage by having someone like Rafsanjani lead a group that would make the case for reaching an understanding. Rafsanjani’s pedigree as Khomeini associate and former president, with ties to the Revolutionary Guard and to the elite more generally, would all argue for him to play this role.

…(T)he fact that the Iranian media is lavishing attention on [Saeed] Jalili certainly suggests that he is Khamenei’s preference, even though he has the thinnest credentials of the lot.

If Jalili does end up becoming the Iranian president, it will be hard to avoid the conclusion that the Supreme Leader has little interest in reaching an understanding with the United States on the Iranian nuclear program.”

Three weeks later, we know not only that Jalili did not win the election, but that the candidate backed with enthusiasm by both Rafsanjani and former reformist president Mohammad Khatami — Hassan Rouhani — did. Moreover, during his campaign, Rouhani did exactly what, in Ross’s assessment, made Rafsanjani’s candidacy unacceptable to Ali Khamenei: he spoke “about Iran’s need to fix the economy and reduce Iran’s isolation internationally…” — themes which he repeated in his 90-minute post-election press conference. In addition, Rouhani — given his 15 years on the Supreme National Security Council — appears to be an excellent vehicle for creating “an image of broad acceptability of [an agreement on Iran's nuclear program] in advance” if Khamenei were interested in such an accord. And, although he isn’t a former president like Rafsanjani, Rouhani’s reputed ability to bridge differences between conservatives, pragmatists and reformists would help Khamenei “widen the circle of decision-making to share the responsibility” of a deal. He would also be well placed to “lead a group that would make the case for reaching an understanding.”

Thus, if we assume, as Ross did three weeks ago, that Khamenei leaves nothing to chance and has the power to do so — a very questionable assumption among actual Iran experts (see here and here for examples) — then we might also see Jalili’s defeat and Rouhani’s surprise victory on what was essentially Rafsanjani’s platform as clear signals that Khamenei is indeed “interested in doing a deal on the Iranian nuclear program.” The only missing element in this scenario was Rafsanjani who, as noted above, strongly backed Rouhani and helped rally the centrists and reformists behind him. In light of Ross’s previous assessments regarding how the supreme leader signals his intentions on nuclear negotiations, would it be unreasonable to expect that Ross would not only be somewhat humbler with respect to his understanding of Iranian politics, but also rather hopeful about prospects for a real deal?

On the question of humility, the answer is not really, at least judging by his latest analysis, entitled “Talk to Iran’s New President. Warily.” Ross doesn’t even mention Jalili, Khamenei’s previously presumed chosen one. And while Ross seems genuinely puzzled by why Khamenei “allowed Mr. Rowhani to win the election,” particularly in light of the fact that the president-elect had “run against current [Khamenei-approved] Iranian policies,” he still sees the supreme leader as all-powerful, implying that Rouhani would not have won had Khamenei not approved of his victory.

As to the meaning of Khamenei’s permitting Rouhani to win, Ross floats four possible options, none of which, however, admits the possibility that Khamenei is prepared “to do a deal” acceptable to the West (a possibility for which Ross, just three weeks before, believed could have been signaled by the Guardian Council’s approval of Rafsanjani’s candidacy). He does entertain the possibility that Rouhani gained Khamenei’s approval for reasons related to the nuclear issue, but strictly for tactical purposes — not to reach a final accord that would preclude Iran’s attaining “breakout capability” (as would presumably have been possible if Rafsanjani had won the presidency):

He [Khamenei] believes that Mr. Rowhani, a president with a moderate face, might be able to seek an open-ended agreement on Iran’s nuclear program that would reduce tensions and ease sanctions now, while leaving Iran room for development of nuclear weapons at some point in the future.

He believes that Mr. Rowhani might be able to start talks that would simply serve as a cover while Iran continued its nuclear program.

Ross, who has been arguing for several months now that Washington needs to drop its approach of seeking incremental confidence-building accords with Iran in favor of making a final ultimatum-like offer (backed up by ever-tougher sanctions and ever-more credible threats of military action) that would permit Tehran to enrich uranium up to five percent (subject to the strictest possible international oversight in exchange for a gradual easing of sanctions), goes on to reject any let-up in pressure on Tehran.

Even if he were given the power to negotiate, Mr. Rowhani would have to produce a deal the supreme leader would accept. So it is far too early to consider backing off sanctions as a gesture to Mr. Rowhani.

We should, instead, keep in mind that the outside world’s pressure on Iran to change course on its nuclear program may well have produced his election. So it would be foolish to think that lifting the pressure now would improve the chances that he would be allowed to offer us what we need: an agreement, or credible Iranian steps toward one, under which Iran would comply with its international obligations on the nuclear issue.”[Emphasis added.]

Now, I, for one, find this reasoning difficult to understand. Ross may be right that external pressure was responsible for Rouhani’s election, but I suspect that it was a good deal more complicated than that, and, in any event, one of the last people I would seek out for an explanation as to why Rouhani won would be Ross, given his assessments of Iranian politics just three weeks ago. But to assert that easing pressure on Iran once Rouhani takes office (as a goodwill gesture) would somehow reduce the chances that Rouhani would be allowed to make concessions on the nuclear issue just doesn’t make much sense, if, for no other reason, virtually all Iran experts agree that Khamenei (and presumably hard-liners in and around his office) don’t believe Washington really wants an agreement because its ultimate goal is regime change. (Just today, Khamenei, while insisting that “resolving the nuclear issue would be simple” if hostile powers put aside their stubbornness, noted, “Of course, the enemies say in their words and letters that they do not want to change the regime, but their approaches are contrary to these words.”) If Khamenei is to be persuaded otherwise, Washington should work to bolster Rouhani and the forces that supported him in the election.

Indeed, most Iran specialists whose work I read argue that Rouhani’s election has really put the “ball in President Obama’s court”, as the International Crisis Group’s Ali Vaez wrote this week. They say that the response should not only be goodwill gestures, such as a congratulatory letter on his inauguration, but far more generous offers than what has been put on the table to date. Vali Nasr, for example, made the point last week when he argued that Rouhani “will likely wait for a signal of American willingness to make serious concessions before he risks compromise.”

For the past eight years, U.S. policy has relied on pressure — threats of war and international economic sanctions — rather than incentives to change Iran’s calculus. Continuing with that approach will be counterproductive. It will not provide Rowhani with the cover for a fresh approach to nuclear talks, and it could undermine the reformists generally by showing they cannot do better than conservatives on the nuclear issue.

…There is now both the opportunity and the expectation that Washington will adopt a new approach to strengthen reformists and give Rowhani the opening that he needs if he is to successfully argue the case for a deal with the P5+1.”

Paul Pillar made a similar point in the National Interest last week:

Rouhani’s election presents the United States and its partners with a test — of our intentions and seriousness about reaching an agreement. Failure of the test will confirm suspicions in Tehran that we do not want a deal and instead are stringing along negotiations while waiting for the sanctions to wreak more damage. …Passage of the test …means not making any proposal an ultimatum that is coupled with threats of military force, which only feed Iranian suspicions that for the West the negotiations are a box-checking prelude to war and regime change.”

“The Iranian electorate has in effect said to the United States and its Western partners, “We’ve done all we can. Among the options that the Guardian Council gave us, we have chosen the one that offers to get us closest to accommodation, agreement and understanding with the West. Your move, America.”

And, in contrast to Ross, who believes that time is fast running out and the “multilateral step-by-step approach …has outlived its usefulness,” the Brookings Institution’s Suzanne Maloney argued in Foreign Affairs that

To overcome the deep-seated (and not entirely unjustified) paranoia of its ultimate decision-maker, the United States will need to be patient. It will need to understand, for example, that Rouhani will need to demonstrate to Iranians that he can produce tangible rewards for diplomatic overtures. That means that Washington should be prepared to offer significant sanctions relief in exchange for any concessions on the nuclear issue. Washington will also have to understand that Rouhani may face real constraints in seeking to solve the nuclear dispute without exacerbating the mistrust of hard-liners.

In spite of this advice, things are moving in the opposite direction. On July 1, tough new sanctions to which Obama has already committed himself will take effect. Among other provisions, they will penalise companies that deal in rials or with Iran’s automotive sector. The Republican-led House is expected to pass legislation by the end of next month (that is, on the eve of Rouhani’s inauguration) that would sharply curb or eliminate the president’s authority to waive sanctions on countries and companies doing any business with Iran, thus imposing a virtual trade embargo on Iran. Other sanctions measures, including an anticipated effort by Republican Sen. Lindsay Graham to get an Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) resolution passed by the Senate after the August recess, are lined up.

It would be good to learn what Ross, who is co-chairing the new Iran task force of the ultra-hawkish Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs, thinks of these new and pending forms of pressure and whether they are likely to improve the chances that Rouhani will be able to deliver a deal.

]]>by Farideh Farhi

I read with great interest the writing of Washington’s new Iran expert, Dennis Ross. With a title like “Don’t Discount the Iranian Election”, I thought, wow! Iran’s contested and improvised politics are finally being taken seriously. What else could that mean other than an acknowledgment that [...]]]>

by Farideh Farhi

I read with great interest the writing of Washington’s new Iran expert, Dennis Ross. With a title like “Don’t Discount the Iranian Election”, I thought, wow! Iran’s contested and improvised politics are finally being taken seriously. What else could that mean other than an acknowledgment that there is politics in Iran, including strategizing by the significant players and the organized and even unorganized forces within the power structures that impact policy choices?

But Ross’s piece is not about competing views of how to run the country, nor is it about Iran. It is all about us.

Iran’s June 14 presidential election has already been engineered by its master designer, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, to send the message that “he has little interest in reaching an understanding with the United States on the Iranian nuclear program.” This, Ross states, “If [Saeed] Jalili does end up becoming the Iranian president.” But he fails to tell us what message Khamenei will send if someone besides Jalili is elected and doesn’t even entertain the possibility that the ballot box results may not be pre-determined — that people might, just might, have something to do with this.

After all, Iranian politics is either about big changes or no changes at all. It is also apparently shaped by one man who knows what he wants, but has to wait for an election to send his message to the US.

Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani failed in his attempt to challenge Khamenei’s authority and now there are no individuals or forces independent of Khamenei remaining. To boot, Khamenei is so independent that he is not moved by anything in society. Everything is generated from his head and his head alone. Like all imagined Oriental despots, Khamenei alone now holds agency in Iran.

The possibility that this election may involve a degree of competition among factions or circles of power, with a good part of the population still undecided about whether to participate or which candidate to vote for, is not even permitted. After all, the “freedom-loving people of Iran” also only have two modes. They either move in unison to protests in the streets or are cowed, again in unison, by the dictates and batons of one man and his cronies. In the first scenario we love them all and in the second we pity them; but in both cases we view them as a herd that occasionally may — at least we hope — stampede toward the goal of what we have.

You’d think that after more than a decade of disastrous policy choices based on the belief that Middle Eastern countries are run by one intractable man, Washington experts would have developed some humility in forwarding their Orientalist presumptions as analysis. But not even ten years of disastrous policies following repeated declarations of so-and-so must go — the last one uttered by President Obama against Bashar al-Assad nearly two years ago — has resulted in any qualms about reducing the complex politics of a post-revolutionary society, which from the beginning has been shaped and reshaped by factions and factional realignments, to a clash of titans invariably moving towards despotism.

What Happened Last Time

Yes, I am aware of what happened in 2009 and even before, when the creeping securitization of the Iranian political system was already well under way, based on both the exaggerated pretext and real fear of external meddling. And yes, I know there is an intense debate among the critics and opposition, be they the reformists or the Green Movement. Activism does not only take place in the streets, it also happens in conversations regarding whether to vote or not.

Given the dynamic state-society relations of the Islamic Republic and societal demands that clearly remain unfulfilled, it would be quite unnatural if at least some parts of Iran’s vibrant, highly urbanized and differentiated society did not debate the legitimacy, role and weight of the electoral system as an integral institution of the Islamic Republic’s identity after what happened in 2009.

This election is deemed important by some and meaningless by others depending on the assessment of the extent to which the masterminds of the 2009 so-called “electoral coup” have managed to consolidate power. But even on the issue of what voting means and whether it will legitimize the Islamic Republic there exists a mostly reasoned debate and conversation. It is a debate and conversation because many people are trying to convince both themselves and their interlocutors that they’re making the right choice. Whatever they decide, they want their action to have political meaning.

Why The Presidential Debates Matter

Another debate also exists within the frames of the available competition. Is there a difference among the candidates in terms of proposed policies? In this conversation, the cynics don’t think that a decision not to vote will undermine the Islamic Republic. Like their counterparts in many other countries, they believe that despite the different rhetoric and promises, the candidates will all end up the same; nothing will change.

But there are also those who are watching for a reason to vote. For some perhaps because a candidate appeals to them. For others, because a candidate scares them.

Iran’s state television recently announced that about 45 million out of a population of 75 million have been watching the presidential debates, the third of which on politics and foreign policy was just held. The interest-level was so high that state TV announced a potential fourth debate.

Perhaps the viewership number has been exaggerated to give the impression of a heated election, but given the conversation I am following on blogs and websites with different viewpoints, it is hard to dispute that many people have been watching.

I’ve always wondered why Iran’s presidential debates have attracted so many viewers. I was in Iran in 1997 when the first debates were held among only four candidates. I had been to Mohammad Khatami’s rallies and knew about his ability to woo through words. What made him difficult to resist as a candidate was precisely the different way he spoke to attract voters. In a country where — in both the monarchist and Islamist eras — what the voter must or should do has always been uttered in every other sentence, a presidential candidate with the art of conversation was something to behold for me. People told me I was crazy and Khatami had no chance. The system would not allow it. But when Khatami came on television and began to talk, things changed.

This isn’t romantic nostalgia. The fundamental changes that have occurred in the relationship between politicians and citizens in Iran can be detected in the way they talk to each other. Iranian clerics have always been good talkers; they know their flock. But finding a language to woo voters is something different.

What’s Happening Now

Just consider what happened in the first presidential debate last week. The highly stilted and child-like format — designed to ensure that the conversation did not spiral out of control — was immediately challenged by the reformist candidate, Mohammadreza Aref, and a couple of others who followed him.

Afterwards the debate was criticized by all the participants and became a subject of both scorn and delicious humor everywhere. The integrity of the institution that held the debate came under question, some said. Others declared the nation had been insulted, the office of the president as a whole denigrated. We are not in kindergarten; treat the audience like adults, the critics shouted.

Iran’s state-run TV effectively was forced to change the format by the second debate, but it was in the third debate that the dam broke and real conversation began on no less a topic than Iran’s handling of its nuclear dossier.

People were somewhat expecting this. Two secretaries of the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) and nuclear negotiators — one former and one current — are, after all, running.

Current negotiator Saeed Jalili has nothing in his portfolio other than his handling of Iran’s nuclear file in negotiations with the five permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany (P5+1), so the framing of his candidacy in terms of his handling of the talks could not be avoided.

But Jalili had to face someone who could not afford to accept his narrative — former negotiator Hassan Rowhani — since Rowhani’s own record is also somewhat tied to nuclear diplomacy. It was an intense conversation with little held back — not about whether Iran should enrich uranium or not, as the discussion is framed in the United States — but about which nuclear negotiating team has been more successful in its interactions with the West. Both played offense and defense.

During Friday’s debate, however, it was not the two nuclear negotiators who broke the dam. It was Ali Akbar Velayati, the former foreign minister and Khamenei’s current senior adviser on foreign affairs. Reacting to Jalili’s certitude over his conduct and disdain for the appeasement of Rowhani’s team, Velayati let loose his criticism of Jalili’s performance by saying, “reading statements does not make diplomacy.” Then Velayati explained to the audience that twice in the past 8 years, attempts to resolve the nuclear issue through negotiations were sabotaged by Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and the foreign ministry. Other candidates followed him, pointing to the lack of success of the current nuclear team.

This is not to say that Jalili demurred. He defended himself and also attacked, rejecting Velayati’s portrayal of his negotiating skills and telling the audience about the shabby way Rowhani’s team was treated by its Western counterparts, egged on by the United States. To prove his point, Jalili even read from Rowhani’s book, which details his negotiations with the EU, UK, France and Germany. Iran gave in and suspended, and the Westerners became louder in their demands, said Jalili. More significantly, Jalili did not talk like anyone’s man; he talked like a believer.

Rowhani did not run away from the conversation either. He’s a believer in his own approach too and disdainful of Jalili’s way — as is Velayati.

Keep in mind that the debates’ audiences don’t watch with a unified eye. Iran, like elsewhere, is not a country with only two abstract actors: “regime” and “people.” There are many people who agree with Jalili regarding the failure of Rowhani’s nuclear team and continue to rally together around this issue. There are also some who identify with his representation of himself as remaining true to being a basiji, or dedicated and lowly soldier of the system.

Then there are those who are genuinely fearful of a Jalili presidency. But even this fear is not expressed in a unified fashion.

Some are petrified by the potential for another 8 years of inept management. I make no claim in knowing who supports Jalili’s candidacy — and would be skeptical of anyone claiming to know. But I can read the websites that support his candidacy. And his potential cabinet ministers look awfully like Ahmadinejad’s ministers.

Sure, some of them were fired by the temperamental president, but their complaints were not about Ahmadinejad’s policies. They were about the bad or “deviant” person he hung around with (Esfandiar Rahim Mashaie). These ministers did get some superficial nods for being fired. But besides a few exceptions, even the bureaucracies they headed don’t consider them particularly good managers and would be worried if they came back.

Just to make a point, perhaps, on Rowhani’s flank, stands his campaign manager, Mohammadreza Nematzadeh, who is considered one of the most able state managers the Islamic Republic has produced (he was removed from his various National Iranian Oil Company posts by Ahmadinejad).

Also making a point is Tehran Mayor Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, who has completely framed his campaign around his managerial and leadership abilities. Qalibaf is only 4 years older than Jalili, but was a commander during the Iran-Iraq war in his early 20s when Jalili remained a soldier. Qalibaf was in the war from the beginning to end while, according to his bio, Jalili joined sometime after 1984. Qalibaf even refuses to declare a campaign slogan. He says his past performance is his slogan.

The Fear Factor

But worrying about Jalili’s abilities is only one side of the story. After carefully listening to a man who has rarely talked inside Iran or said anything beyond the nuclear issue, some are terrified of his ideas about the cultural and social arenas. Oh no, not again. Or, oh no, he seems exactly like Ahmadinejad without his sense of humor, or, without his opportunism, like a collective reaction to at least a good part of more secular northern Tehran and surely some other cities and provinces too.

Jalili is even scarier than Ahmadinejad precisely because he’s deemed a believer and not an opportunist populist. If these secular folks vote — and so far they have been deemed least likely to vote — it will be out of a fear similar to that experienced by unhappy Obama 2012 voters who would not have voted had the alternative not been so frightening. They worry that Jalili may be Khamenei’s man; but they are even more worried about the possibility that, with him, Jalili will bring a group of righteous believers to power who even Khamenei cannot control. To them, Jalili represents the nightmare of continuity plus.

Jalili’s Strategy

Jalili understands this fear and frankly doesn’t give a hoot about it. Like his Christian conservative counterpart in the US, he has a lament. He and his support base think the previous presidents have not allowed true believers to express themselves sufficiently through their press or art. They think that capturing the executive branch will make a difference. Jalili knows that what limits the spread of his cherished ideas is not the state but a society worried that some of those ideas may take Iran to more dangerous places against a powerful enemy: the United States. I suspect he knows this because his campaign strategy suggests he is aware of the limitations faced by his co-believers.

In his campaign commercials, Jalili has explicitly tried to sell himself as Khamenei’s favorite and in doing so, adeptly used the Western press, which declared him the “frontrunner” on the same day (May 21) the Guardian Council announced the qualified candidates!

Jalili achieved this frontrunner designation through an understanding of how foreign press and Diaspora punditry works its way back into Iranian politics. After his qualification he gave his first interview to a Western reporter and later used the interview in a commercial. His strategy compelled his competitors and their supporters to publicly state that the pretention of having Khamenei’s support is just that: pretension.

What The Polls Say

Also working against Jalili are the announced polls, sometimes daily. Unlike the Western press, even hardline websites are not calling Jalili a front-runner, a situation completely different from 2009 when hardline newspapers such as Kayhan, as early as May, were announcing — without explaining the methodology, numbers polled, etc. — a 63-percent preference for Ahmadinejad, which turned out to be the eventual announced result.

Today, across the political spectrum, Qalibaf is acknowledged as the frontrunner. The most Jalili supporters are claiming is that he will be one of the two going to the second round. Whether this is a wish or a plan, no one knows. But there is little doubt that the belief in a predetermined outcome reduces one’s desire to vote.

But going back to Jalili, his problem is compounded by the fact that the polls have him way behind Qalibaf. Polls are notoriously politicized in Iran, but one of the interesting aspects of Iranian electoral politics is that despite the 2009 disaster, some rather serious pollsters are still taking fluctuations in voter thinking seriously.

One particularly interesting site with a daily tracking poll can be accessed here. Hossein Ghazian, a well known sociologist/pollster who was arrested for releasing polls that some authorities didn’t like, is one of the site’s masterminds. It specifies the number of people who are called on a 4-day rolling basis, as well as margins of error. Apparently, 35-percent of the people who were called refused to respond. Ghazian told me that he is not going to spend time defending the spread, but does think his approach can reveal quite a bit about the movement of close to 60-percent of the people who are still undecided about which candidate to vote for (as distinct from the people who have already decided not to vote). In this poll, Jalili is in third place, although his numbers are slowly improving.

I do not know what to think of these numbers, but I find the mere fact of their public emergence (since polls existed behind the closed doors of the Intelligence Ministry before) — even if they are not totally accurate — an important sign, for now, that at least a good sector of the Iranian society is interested in a more differentiated understanding of Iran; an Iran in which its citizens are not mere tools of a despot’s engineering.

Why Iran’s Election Matters

Jalili may still get elected, but so far he has been unable to sell himself as a candidate for the majority. In fact, no one has — not even Qalibaf — making a second round on June 21 a real possibility. If one has any respect for the agency of the multi-voiced citizens of Iran, observing their decisions, including whether they vote or not, is the least that can be done.

Declaring a candidate a frontrunner based on a presumption may be a cost-free exercise for Dennis Ross, but it is not one for Iran’s contentious political terrain. Jalili’s attempt to get himself anointed as the favorite was intended to make his non-election look like a challenge to Khamenei’s authority while convincing the latter to support his candidacy out of a fear of the further erosion of his authority.

His opponents’ turn of the debate away from Jalili’s relationship with Khamenei towards his conduct as the Secretary of the National Security Council — and not merely a nuclear negotiator — was a counter to this strategy.

During Friday’s debate, Jalili was called upon to talk about other issues related to national security and the way he runs the SNSC since he, as the secretary of this body, is also the director of its staff. On Thursday, Rowhani’s representative, former deputy foreign minister Mahmoud Vaezi, did something more damning. When Ali Bagheri tried to say that Jalili was really the implementer of policies decided elsewhere, Vaezi thundered back and criticized Jalili for not taking his job as the Secretary of the SNSC seriously as others have in the past.

Yes, Khamenei is being cleared here as the real initiator of the past few years’ policies, but with intent. The reformists and centrists have learned that powerful institutions and people who are threatened can react with quite a bit of violence (Syria, anyone?) if the threat is deemed existential.

They understand that pulling the country toward the center and away from the securitized environment that has been imposed in the past few years involves focusing on the criticisms and failures of the policies pursued and not core institutions. In other words, their language must also stop being the language of purge.

This is at least what Abbas Abdi, one of Iran’s well-known reformist journalists, seems to be relaying when he blogs (in a highly unusual piece since he has been a harsh critic and openly stated that the man’s recent candidacy was a mistake) praise for former president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani.

After telling his readers about the years he was in prison and how his livelihood had been repeatedly undermined by the authorities, Abdi said he will still vote without revealing his choice (the prospect of Iran turning into Syria after domestic splits scares him). He says:

Critics should learn from Mr. Hashemi’s behavior. The critical leaders not only failed to bring about reform through their own elimination, more than ever they also reduced their own impact on society. But Hashemi, after a disqualification that no one’s mind could even conceive, did not even change his tone and even more interesting called for the creation of a political epic and last Saturday went to [a meeting of] the Expediency Council and ran the meeting next to [the Guardian Council Secretary] Mr. Jannati. And he will be one of the first people who will vote. It was from the same angle that I also participated in the last parliamentary election. From this [vantage point] my main issue under the current conditions is opening this path and returning critics to the official arena of the country and the person I vote for is of secondary importance. Of course, I have a preference between Rowhani and Aref. But because of the importance I give to reformist unity, I do not like to state my preference before this unity… I cannot say for sure but my feeling is that, despite what is imagined, the situation after the June 14 election can help improve societal trends.

Iran’s election should not be discounted, but not because of Khamenei’s message to us. It should be given attention and appreciated — no matter the result — as part and parcel of Iran’s multi-layered, vibrant politics and because some people are refusing to give up hope for gradual change, even if those changes don’t seem particularly grand at the moment.

]]>by Jasmin Ramsey

Dennis Ross, President Obama’s former top Middle East aide, writes that the exclusion of Hashemi Rafsanjani from Iran’s June 14 election signals that Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is uninterested in a nuclear deal:

I say that not because Rafsanjani would have been capable of initiating [...]]]>

by Jasmin Ramsey

Dennis Ross, President Obama’s former top Middle East aide, writes that the exclusion of Hashemi Rafsanjani from Iran’s June 14 election signals that Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is uninterested in a nuclear deal:

I say that not because Rafsanjani would have been capable of initiating a deal on his own — any deal he might strike would still have to be acceptable to the Supreme Leader — but because if the Supreme Leader were interested in an agreement, he would probably want to create an image of broad acceptability of it in advance. Rather than having only his fingerprints on it, he would want to widen the circle of decision-making to share the responsibility. And he would set the stage by having someone like Rafsanjani lead a group that would make the case for reaching an understanding. Rafsanjani’s pedigree as Khomeini associate and former president, with ties to the Revolutionary Guard and to the elite more generally, would all argue for him to play this role.

Alireza Nader, a Rand analyst specializing on Iran, tells LobeLog the election has more to do with the power struggle in Tehran than Iran’s nuclear program. “Rafsanjani’s disqualification was a result of the rivalry between the former president and Khamenei. The nuclear program is important in Khamenei’s calculations, but it doesn’t appear to be the most important motivation,” said Nader.

In a Rand report released today, Nader expands on this notion, arguing that Khamenei is “primarily concerned with regime security”:

Khamenei will still play the decisive role on nuclear policy after the election. But the next Iranian president could have an opportunity to defuse some of the tensions created by Ahmadinejad. This is not to suggest that the election will lead to an immediate resolution of the crisis, but it is safe to assume that the next president will be less polarizing and more diplomatic than his predecessor. This could provide a limited easing of the nuclear stalemate, but the true problem for Iran’s nuclear program stems from conflicting interests between the United States and Iran, not from vexing personalities.Ross, unlike Nader, does not even allow for the possibility that a new presidential era in an economically pressured Iran — now free from the rabble-rousing Mahmoud Ahmadinejad — could present an opening for a less “intransigent position.”

Unlike Nader, Ross doesn’t even allow for the possibility that a new presidential era in an increasingly pressured Iran — free from the rabble-rousing Mahmoud Ahmadinejad — could present an opening for a less intransigent position. Still, Nader admits that Iran’s next president is likely to pursue the Supreme Leader’s nuclear policy:

…Saeed Jalili, Iran’s chief nuclear negotiator with the P5+1 and one of the main presidential candidates, tends to parrot Khamenei’s discourse of “resistance” regarding the United States. From Tehran’s standpoint, the answer to new and harsher sanctions could be a policy of greater intransigence, a policy that would be supported by both Khamenei and possibly the new president.

As if on cue, the Supreme Leader made another speech yesterday (for the anniversary of Ayatollah Khomeini’s death) urging the presidential candidates not to submit to Western pressure. “Some, following this incorrect analysis – that we should make concessions to the enemies to reduce their anger – have put their interests before the interests of the Iranian nation. This is wrong,” he said.

The US’ current approach has failed to compel Tehran to change it’s nuclear stance, so why not try something new? Enter the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, which published a report on the Iranian sanctions regime this week. ”To make genuine progress on the Iranian nuclear issue, the Obama administration and Congress must shift their focus toward sanctions relief and compromise, rather than sticking with the pressure-only approach that’s proving increasingly counterproductive,” write Usha Sahay and Laicie Heeley. Of course, the opposite seems to be happening.

]]>By David Isenberg

Apart from death and taxes, one other thing has also appeared inevitable, at least for the past two decades: Iran will acquire a nuclear weapons capability.

Yet, despite all the near frantic demands for sanctions, clandestine action, sabotage, and outright military strikes to prevent Iran’s presumed inexorable march [...]]]>

By David Isenberg

Apart from death and taxes, one other thing has also appeared inevitable, at least for the past two decades: Iran will acquire a nuclear weapons capability.

Yet, despite all the near frantic demands for sanctions, clandestine action, sabotage, and outright military strikes to prevent Iran’s presumed inexorable march towards that capability, one thing keeps getting overlooked: Iran has not managed to develop a nuclear weapon.

How is that possible? As states go, Iran has a reasonably well-developed scientific and industrial infrastructure, an educated workforce capable of working with advanced technologies, and lots of money. If Pakistan, starting from a much lower level, could develop nuclear weapons, why hasn’t Iran?

That overlooked question was the subject of an important but largely ignored past article, “Botching the Bomb: Why Nuclear Weapons Programs Often Fail on Their Own — and Why Iran’s Might, Too” in Foreign Affairs journal.

In the May/June 2012 issue, Jacques E. C. Hymans, an International Relations Associate Professor at the University of Southern California and author of the book Achieving Nuclear Ambitions: Scientists, Politicians, and Proliferation (from which his article was adapted) wrote:

The Iranians had to work for 25 years just to start accumulating uranium enriched to 20 percent, which is not even weapons grade. The slow pace of Iranian nuclear progress to date strongly suggests that Iran could still need a very long time to actually build a bomb — or could even ultimately fail to do so. Indeed, global trends in proliferation suggest that either of those outcomes might be more likely than Iranian success in the near future. Despite regular warnings that proliferation is spinning out of control, the fact is that since the 1970s, there has been a persistent slowdown in the pace of technical progress on nuclear weapons projects and an equally dramatic decline in their ultimate success rate.

To paraphrase Sherlock Homes, Iran is an example of a nuclear dog that has not barked. In Hyman’s view, Iran’s lack of progress can only partly be attributed to US and international nonproliferation efforts.

But the primary reason is:

…mostly the result of the dysfunctional management tendencies of the states that have sought the bomb in recent decades. Weak institutions in those states have permitted political leaders to unintentionally undermine the performance of their nuclear scientists, engineers, and technicians. The harder politicians have pushed to achieve their nuclear ambitions, the less productive their nuclear programs have become.

Conversely, US and Israeli efforts may actually be helping Iran to someday achieve a nuclear weapons capability.

Meanwhile, military attacks by foreign powers have tended to unite politicians and scientists in a common cause to build the bomb. Therefore, taking radical steps to rein in Iran would be not only risky but also potentially counterproductive, and much less likely to succeed than the simplest policy of all: getting out of the way and allowing the Iranian nuclear program’s worst enemies — Iran’s political leaders — to hinder the country’s nuclear progress all by themselves.

Generally examining the progress of contemporary aspiring nuclear weapons states, Hymans notes that seven countries launched dedicated nuclear weapons projects before 1970, and all of them succeeded in relatively short order. By contrast, of the ten countries that have launched dedicated nuclear weapons projects since 1970, only three have achieved a bomb. And only one of the six states that failed — Iraq — had made much progress toward its ultimate goal by the time it gave up trying. (The jury is still out on Iran’s program.) What’s more, even the successful projects of recent decades have required a long time to achieve their goals. The average timeline to the bomb for successful projects launched before 1970 was about seven years; the average timeline to the bomb for successful projects launched after 1970 has been about 17 years.

In the case of Iran, Hymans notes:

Iran’s nuclear scientists and engineers may well find a way to inoculate themselves against Israeli bombs and computer hackers. But they face a potentially far greater obstacle in the form of Iran’s long-standing authoritarian management culture. In a study of Iranian human-resource practices, the management analysts Pari Namazie and Monir Tayeb concluded that the Iranian regime has historically shown a marked preference for political loyalty over professional qualifications. “The belief,” they wrote, “is that a loyal person can learn new skills, but it is much more difficult to teach loyalty to a skilled person.” This is the classic attitude of authoritarian managers. And according to the Iranian political scientist Hossein Bashiriyeh, in recent years, Iran’s “irregular and erratic economic policies and practices, political nepotism and general mismanagement” have greatly accelerated. It is hard to imagine that the politically charged Iranian nuclear program is sheltered from these tendencies.

Hymans accordingly derived four lessons.

- The first is to be wary of narrow, technocentric analyses of a state’s nuclear weapons potential. Recent alarming estimates of Iran’s timeline to the bomb have been based on the same assumptions that have led Israel and the United States to consistently overestimate Iran’s rate of nuclear progress for the last 20 years. The majority of official US and Israeli estimates during the 1990s predicted that Iran would acquire nuclear weapons by 2000. After that date passed with no Iranian bomb in sight, the estimate was simply bumped back to 2005, then to 2010, and most recently to 2015. The point is not that the most recent estimates are necessarily wrong, but that they lack credibility. In particular, policymakers should heavily discount any intelligence assessments that do not explicitly account for the impact of management quality on Iran’s proliferation timeline.

- The second is that policymakers should reject analyses based on assumptions about a state’s capacity to build nuclear programs in secret. Ever since the mid-1990s, official proliferation assessments have freely extrapolated from minimal data, a practice that led US intelligence analysts to wrongly conclude that Iraq had reconstituted its weapons of mass destruction programs after the Gulf War. The US must guard against the possibility of an equivalent intelligence failure over Iran. This is not to deny that Tehran may be keeping some of its nuclear work secret. But it is simply unreasonable to assume, for example, that Iran has compensated for the problems it has faced with centrifuges at the Natanz uranium-enrichment facility by hiding better-working centrifuges at some unknown facility. Indeed, when Iran has tried to hide weapons-related activities in the past, it has often been precisely because the work was at the very early stages or was going badly.

- The third is that states that poorly manage their nuclear programs can bungle even the supposedly easy steps of the process. For instance, based on estimates of the size of North Korea’s plutonium stockpile and the presumed ease of weapons fabrication, US intelligence agencies thought that by the 1990s, North Korea had built one or two nuclear weapons. But in 2006, North Korea’s first nuclear test essentially fizzled, making it clear that the “hermit kingdom” did not have any working weapons at all. Even its second try, in 2009, did not work properly. Similarly, if Iran eventually does acquire a significant quantity of weapons-grade highly enriched uranium, this should not be equated with the possession of a nuclear weapon.

- The fourth lesson is to avoid acting in a way that might motivate scientific and technical workers to commit themselves more firmly to the nuclear weapons project. Nationalist fervor can partially compensate for poor organization. Accordingly, violent actions, such as aerial bombardments or assassinations of scientists, are a loser’s bet. As shown by the consequences of the Israeli attack on Osiraq, such strikes are liable to unite the state’s scientific and technical workers behind their otherwise illegitimate political leadership. Acts of sabotage, such as the Stuxnet computer worm, which damaged Iranian nuclear equipment in 2010, stand at the extreme boundary between sanctions and violent attacks, and should therefore only be undertaken after extremely thorough consideration.

- David Isenberg runs the Isenberg Institute of Strategic Satire (Motto: Let’s stop war by making fun of it.). He is author of the book Shadow Force: Private Security Contractors in Iraq and blogs at The PMSC Observer and the Huffington Post. He is a senior analyst at Wikistrat, an adjunct scholar at the CATO Institute, and a Navy veteran.

Photo: Iran’s first nuclear power plant in Bushehr, Iran, on August 21, 2010. UPI/Maryam Rahmanianon.

]]>Gary Sick, who served as an Iran specialist on the National Security Council staffs of Presidents Ford, Carter and Reagan, speaks to Foreign Affairs editor Gideon Rose about an article that he wrote for the magazine in 1987, which still holds up today.

Also don’t miss Dr. [...]]]>

Gary Sick, who served as an Iran specialist on the National Security Council staffs of Presidents Ford, Carter and Reagan, speaks to Foreign Affairs editor Gideon Rose about an article that he wrote for the magazine in 1987, which still holds up today.

Also don’t miss Dr. Sick’s review of a superb new book on US policy during the Iran-Iraq war for IPS News.

]]>Michael Ledeen, a neoconservative polemicist and long-time Iran hawk who joined the Foundation for Defense of Democracies after leaving the American Enterprise Institute in 2008, is being honest when he reminds us here that he has opposed direct US military intervention in Iran. For Ledeen, Iranian-regime change is more attainable if [...]]]>

Michael Ledeen, a neoconservative polemicist and long-time Iran hawk who joined the Foundation for Defense of Democracies after leaving the American Enterprise Institute in 2008, is being honest when he reminds us here that he has opposed direct US military intervention in Iran. For Ledeen, Iranian-regime change is more attainable if it’s executed from the ground up, and the US should do everything it can to facilitate that process. In 2010 he unapologetically argued that the US should covertly or openly support regime change-inclined Iranians during a debate at the Atlantic Council and reiterated that argument in “Takedown Tehran“ this year. (For some reason Ledeen seems to think that the Green Movement would invite the regime-change-oriented US support he advocates, even if key opposition figures have opposed the broad sanctions that he endorses. This may be due to his allegedly well-informed sources, some of whom have led him astray in the past.)

Michael Ledeen, a neoconservative polemicist and long-time Iran hawk who joined the Foundation for Defense of Democracies after leaving the American Enterprise Institute in 2008, is being honest when he reminds us here that he has opposed direct US military intervention in Iran. For Ledeen, Iranian-regime change is more attainable if it’s executed from the ground up, and the US should do everything it can to facilitate that process. In 2010 he unapologetically argued that the US should covertly or openly support regime change-inclined Iranians during a debate at the Atlantic Council and reiterated that argument in “Takedown Tehran“ this year. (For some reason Ledeen seems to think that the Green Movement would invite the regime-change-oriented US support he advocates, even if key opposition figures have opposed the broad sanctions that he endorses. This may be due to his allegedly well-informed sources, some of whom have led him astray in the past.)

In any case, sanctions should be part of the US regime-change strategy, argues Ledeen, who promoted the US invasion of Iraq (although he later denied doing so), but sanctions alone will never be the means to his desired end:

But I don’t know anyone this side of the White House who believes that sanctions, by themselves, will produce what we should want above all: the fall of the Tehran regime that is the core of the war against us. To accomplish that, we need more than sanctions; we need a strategy for regime change.

Like fellow ideologues — such as Bret Stephens, a Wall Street Journal deputy editor and “Global View” columnist – Ledeen argues that the US must also execute a war strategy with Iran because like it or not, we’re already at war (for a closer look at this line of reasoning, see Farideh’s post):

But even if all these are guided from Washington and/or Jerusalem, it still does not add up to a war-winning strategy, which requires a clearly stated mission from our maximum leaders. We need a president who will say “Khamenei and Ahmadinejad must go.” He must say it publicly, and he must say it privately to our military, to our diplomats, and to the intelligence community.

Without that commitment, without that mission — and it’s hard to imagine it, isn’t it? — we’ll continue to spin our wheels, mostly playing defense, sometimes enacting new sanctions, sometimes wrecking the mullahs’ centrifuges, forever hoping that the mullahs will make a deal. Until the day when one of those Iranian schemes to kill even more Americans works out, and we actually catch them in the act. Then our leaders will say “we must go to war.”

But Ledeen’s Washington Times column this week suggests that he may be pivoting toward the military option:

I have long opposed military action against the Iranian regime. I believe we should instead support democratic revolution. However, our failure to work for regime change in Iran and our refusal to endorse Mr. Netanyahu’s call for a bright “red line” around the mullahs’ nuclear weapons program, makes war more likely, as similar dithering and ambiguity have so often in the past.

Interestingly, in August Ledeen stated that the Israeli strategy was to push the US to attack Iran:

…Israel does not want to do it. For as long as I can remember, the Israelis have been trying to get U.S. to do it, because they have long believed that Iran was so big that only a big country could successfully take on the mullahs in a direct confrontation. So Israel’s Iran policy has been to convince us to do whatever the Israelis think is best. And while they’re willing to do their part, they are very reluctant to take on the entire burden.

“Faster, Please!”, right?

]]>In the 1970s Edgar Dean Mitchell, a retired US Navy Captain and the sixth person to walk on the moon, summarized international politics while describing his experience of seeing the earth from the moon:

It was a beautiful, harmonious, peaceful-looking planet, blue with white clouds, and one that gave you [...]]]>

In the 1970s Edgar Dean Mitchell, a retired US Navy Captain and the sixth person to walk on the moon, summarized international politics while describing his experience of seeing the earth from the moon:

It was a beautiful, harmonious, peaceful-looking planet, blue with white clouds, and one that gave you a deep sense … of home, of being, of identity. It is what I prefer to call instant global consciousness, a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it. From out there on the moon, international politics look so petty. You want to grab a politician by the scruff of the neck and drag him a quarter of a million miles out and say, “Look at that, you son of a bitch.”

– Edgar Mitchell, Apollo 14, 1971

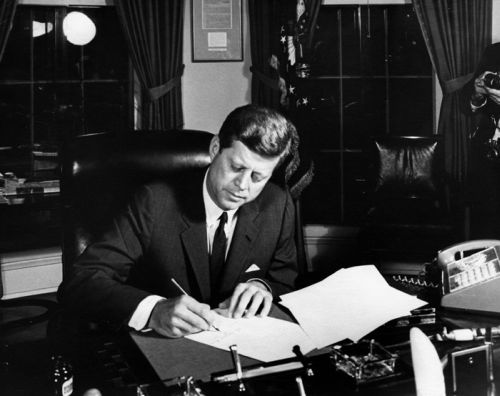

]]>It was exactly 50 years ago when then-President John F. Kennedy took to the airwaves to inform the world that the Soviet Union was introducing nuclear-armed missiles into Cuba and that he had ordered a blockade of the island – and would consider stronger action – to force their removal.

[...]]]> It was exactly 50 years ago when then-President John F. Kennedy took to the airwaves to inform the world that the Soviet Union was introducing nuclear-armed missiles into Cuba and that he had ordered a blockade of the island – and would consider stronger action – to force their removal.

It was exactly 50 years ago when then-President John F. Kennedy took to the airwaves to inform the world that the Soviet Union was introducing nuclear-armed missiles into Cuba and that he had ordered a blockade of the island – and would consider stronger action – to force their removal.

“It was the most chilling speech in the history of the U.S. presidency,” according to Peter Kornbluh of the National Security Archive, who has spent several decades working to declassify key documents and other material that would shed light on the 13-day crisis that most historians believe brought the world closer to nuclear war than at any other moment.

Indeed, Kennedy’s military advisers were urging a pre-emptive strike against the missile installations on the island, unaware that some of them were already armed.

Several days later, the crisis was resolved when Soviet President Nikita Krushchev appeared to capitulate by agreeing to withdraw the missiles in exchange for a U.S. pledge not to invade Cuba.

“We’ve been eyeball to eyeball, and the other fellow just blinked,” exulted Secretary of State Dean Rusk in what became the accepted interpretation of the crisis’ resolution.

“Kennedy’s victory in the messy and inconclusive Cold War naturally came to dominate the politics of U.S. foreign policy,” write Leslie Gelb, president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations in a recent foreignpolicy.com article entitled “The Myth That Screwed Up 50 Years of U.S. Foreign Policy.”

“It deified military power and willpower and denigrated the give-and-take of diplomacy,” he wrote. “It set a standard for toughness and risky dueling with bad guys that could not be matched – because it never happened in the first place.”

What the U.S. public didn’t know was that Krushchev’s concession was matched by another on Washington’s part as a result of secret diplomacy, conducted mainly by Kennedy’s brother, Robert, and Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin.

Indeed, in exchange for removing the missiles from Cuba, Moscow obtained an additional concession by Washington: to remove its own force of nuclear-tipped Jupiter missiles from Turkey within six months – a concession that Washington insisted should remain secret.

“The myth (of the Cuban missile crisis), not the reality, became the measure for how to bargain with adversaries,” according to Gelb, who interviewed many of the principals.

Writing in a New York Times op-ed last week, Michael Dobbs, a former Washington Post reporter and Cold War historian, noted that the “eyeball to eyeball” image “has contributed to some of our most disastrous foreign policy decisions, from the escalation of the Vietnam War under (Lyndon) Johnson to the invasion of Iraq under George W. Bush.”

Dobbs also says Bush made a “fateful error, in a 2002 speech in Cincinnati when he depicted Kennedy as the father of his pre-emptive war doctrine. In fact, Kennedy went out of his way to avoid such a war.”

To Graham Allison, director of the Belfer Center at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, whose research into those fateful “13 days in October” has brought much of the back-and-forth to light, “the lessons of the crisis for current policy have never been greater.”

In a Foreign Affairs article published last summer, he described the current confrontation between the U.S. and Iran as “a Cuban missile crisis in slow motion”.

Kennedy, he wrote, was given two options by his advisers: “attack or accept Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba.” But the president rejected both and instead was determined to forge a mutually acceptable compromise backed up by a threat to attack Cuba within 24 hours unless Krushchev accepted the deal.

Today, President Barack Obama is being faced with a similar binary choice, according to Allison: to acquiesce in Iran’s acquisition of a nuclear bomb or carry out a preventive air strike that, at best, could delay Iran’s nuclear programme by some years.

A “Kennedyesque third option,” he wrote, would be an agreement that verifiably constrains Iran’s nuclear programme in exchange for a pledge not to attack Iran so long as it complied with those constraints.

“I would hope that immediately after the election, the U.S. government will also turn intensely to the search for something that’s not very good – because it won’t be very good – but that is significantly better than attacking on the one hand or acquiescing on the other,” Allison told the Voice of America last week.

This very much appears to be what the Obama administration prefers, particularly in light of as-yet unconfirmed reports over the weekend that both Washington and Tehran have agreed in principle to direct bilateral talks, possibly within the framework of the P5+1 negotiations that also involve Britain, France, China, Russia and Germany, after the Nov. 6 election.

Allison also noted a parallel between the Cuban crisis and today’s stand-off between the U.S. and Iran – the existence of possible third-party spoilers.

Fifty years ago, Cuban Prime Minister Fidel Castro had favoured facing down the U.S. threat and even launching the missiles in the event of a U.S. attack.

But because the Cubans lacked direct control over the missiles, which were under Soviet command, they could be ignored. Moreover, Kennedy warned the Kremlin that it “would be held accountable for any attack against the United States emanating from Cuba, however it started,” according to Allison.

The fact that Israel, which has repeatedly threatened to attack Iran’s nuclear sites unilaterally, actually has the assets to act on those threats makes the situation today more complicated than that faced by Kennedy.

“Due to the secrecy surrounding the resolution of the Cuban missile crisis, the lesson that became ingrained in U.S. foreign policy-making was the importance of a show of force to make your opponent back down,” Kornbluh told IPS.

“But the real lesson is one of commitment to diplomacy, negotiation and compromise, and that was made possible by Kennedy’s determination to avoid a pre-emptive strike, which he knew would open a Pandora’s box in a nuclear age.”

]]>Sunday’s New York Times story that the US and Iran have agreed in principle to direct bilateral negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program provides opportunity for a more honest conversation on Iran than the presidential candidates have had so far. Well, at least this is my hope.

I know the NYT [...]]]>

Sunday’s New York Times story that the US and Iran have agreed in principle to direct bilateral negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program provides opportunity for a more honest conversation on Iran than the presidential candidates have had so far. Well, at least this is my hope.

Sunday’s New York Times story that the US and Iran have agreed in principle to direct bilateral negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program provides opportunity for a more honest conversation on Iran than the presidential candidates have had so far. Well, at least this is my hope.

I know the NYT report has already been rejected by the US and Iran. But the rejections on both sides have a similar quality. Despite the Iranian refusal to meet with the US in the talks that began in Istanbul last April, neither has rejected the possibility of bilateral talks as an outgrowth of the P5+1 process. And both have said that talks within the P5+1 frame will begin in late November (time and place to be determined). In any case, the P5+1 frame has increasingly become a venue dominated by US demands.

But the value of the NYT revelation or leak is not in the reporting of an agreement on a potential meeting but in the impact it may have on the nature of the conversation about Iran’s nuclear program. The reality is that the presidential race has so far managed to avoid the real Iran question. Certainly there has been grandstanding and threats. There was the frenzy over the need to set red line or deadline for Iran which was thankfully calmed — at least temporarily — by Prime Minister’s Benjamin Netanyahu’s inane performance at the UN.

The campaign has also been full of sounds bites regarding the seeming contrast between “having Israel’s back” and “not allowing daylight between Israel and the United States”. But there has been no conversation regarding the rapidly approaching decision time regarding Iran. No conversation regarding whether the United States, after years of offering what it knew would be refused, is willing to offer something that Iran can accept.

Everyone knows what the elements of the offer are: limits on levels of enrichment combined with a more robust inspection regime in exchange for calibrated reduction of some of the sanctions. There are many details to be worked out in difficult negotiations, but these details cannot even begin to be addressed without public acceptance of some enrichment in Iran or the acknowledgment of Iran’s proverbial “inalienable right.”

Why do I say that there is a rapidly approaching decision time for which direction to go in? Well, sanctions have worked to create economic havoc in Iran. No doubt both President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Leader Ali Khamenei are primarily responsible for the deteriorating conditions. But their responsibility lies not in their incompetence in managing the economy per se but in their miscalculation. Khamenei, in particular, suspected negotiations would not go anywhere (at least, this is what he keeps saying) but he failed to prepare the country for his publicized “resistance economy.”

A resistance economy cannot be created overnight; certainly not when the economic helm of the country is in the combined hands of a populist president who underestimated the force of sanctions and a cantankerous Parliament caught between the demands of higher ups and pressures from lobbies and constituencies.

Not that Khamenei does not want a deal. He does and the encounters of the past four years have exhibited his openness to talks whenever there was hope in or detection of a degree of flexibility in the US position. But these encounters have also shown that he perceives himself as standing at the helm of a highly contentious political terrain that demands addressing certain bottom lines for Iran.

With the draconian economic measures imposed on Iran in the past year, the same political terrain makes quite impossible the acceptance of a deal that does not bring about some immediate, palpable, even if small, relaxation of the sanctions regime.

Some would say that this is precisely why this is no time for flexibility on the part of the United States. It will be throwing a lifeline to Khamenei and “them,” whoever they are. Now that sanctions are working, going for the throat is the right thing to do, they say. In response to this argument, which is also prevalent among some in the Iranian Diaspora who yell hard, accusing any country negotiating with Iran of being a traitor to the cause of the Iranian people, I would say that they are not adequately aware of the social and ideological forces than can be mobilized inside Iran to maintain a defiant, albeit limping, country.

Unless Khamenei and company are given a way out of the mess they have taken Iran into (with some help from the US and company), chances are that we are heading into a war in the same way we headed to war in Iraq. A recent Foreign Affairs article by Ralf Ekeus, the former executive chairman of the UN special Commission on Iraq, and Malfrid-Braut hegghammer, is a good primer on how this could happen.

The reality is that the current sanctions regime does not constitute a stable situation. First, the instability (and instability is different from regime change as we are sadly learning in Syria) it might beget is a constant force for policy re-evaluation on all sides (other members of the P5+1 included). Second, maintaining sanctions require vigilance while egging on the sanctioned regime to become more risk-taking in trying to get around them. This is a formula for war and it will happen if a real effort at compromise is not made. Inflexibility will beget inflexibility.

An additional benefit from directing the conversation away from whether to attack Iran and how to sanction it further is the positive impact on the nuclear debate inside Iran. There is no doubt in my mind that the conversation that has focused on attacking or sanctioning Iran until it kneels or submits has had the effect of making the hardliners defiantly louder and silencing those pushing for the resolution of the “Amrika issue.”

The loudness of the defiant folks rests on a simple argument again articulated last week in no uncertain terms by Khamenei himself: America’s problem with Iran is not the nuclear issue and talks for the US are not intended to resolve the nuclear standoff; they are a means to extract surrender from Iran.

If Khamenei is not correct, then a clearer public articulation of the extent of compromises the United States may be contemplating in order to resolve the nuclear standoff can encourage a conversation inside Iran as well. My bet is that it will also empower those pushing for Iran to show a bit more flexibility in its bottom line.

]]>Rolf Ekéus, who was executive chairman for the UN Special Commission on Iraq between 1991 and 1997, writes with Målfrid Braut-Hegghammer, a nuclear expert at Standford University, on the parallels between the run-up to the Iraq War and the present state of negotiations between Tehran and the international community.

Rolf and Braut-Heggehammer place the onus [...]]]>

Rolf Ekéus, who was executive chairman for the UN Special Commission on Iraq between 1991 and 1997, writes with Målfrid Braut-Hegghammer, a nuclear expert at Standford University, on the parallels between the run-up to the Iraq War and the present state of negotiations between Tehran and the international community.

Rolf and Braut-Heggehammer place the onus for the collapse of UN inspection efforts in Iraq on the Clinton Administration’s decision to explicitly denote US policy in Iraq as regime change, effectively abandoning the post-Desert Storm “dual containment” strategy and laying the groundwork for the Bush Administration’s 2003 decision to go to war:

Between 1991 and 1997, Iraq moved steadily forward with disarmament. Even as it did so, of course, Iraqi leaders tested the resolve of the international community by frequently obstructing the inspectors. But the regime was determined to get the United Nations to lift the sanctions and realized that the international community remained committed to enforcing the cease-fire terms. So between 1995 and 1997, Iraq cooperated more thoroughly. By the first few months of 1997, Iraq had completed the disarmament phase of the cease-fire agreement and the United Nations had developed a monitoring system designed to detect Iraqi violations of the nonproliferation requirement.

At this point, several members of the Security Council argued that it was time to conduct a full review of Iraq’s progress in preparation for lifting the sanctions. But the United States took a different view. In the spring of 1997, former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright gave a speech at Georgetown University in which she stated that even if the weapons provisions under the cease-fire resolution were completed, the United States would not agree to lifting sanctions unless Saddam had been removed from power.

With regime change now a stated U.S. objective and the easing of economic sanctions off the table, Saddam lost his appetite for cooperation. He foiled the inspectors at every turn and finally ousted them after a 1998 U.S.-British bombing campaign targeting Saddam’s headquarters, air defenses and security organizations that was allegedly intended to weaken Iraq’s ability to produce weapons of mass destruction (WMD). The UN Security Council could not rally together in support of the inspection regime or reform the sanctions, and misinformation about Iraqi weapons capabilities spread. In 2003, the George W. Bush administration used faulty assessments of the country’s WMD program to make the case for war. Due to the information vacuum that followed the four-year absence of inspections, those allegations could not be easily countered. If monitoring had remained in place, the international community would have been confident in the fact that Iraq’s ability to make WMD had not been reconstituted. A costly war could have been avoided.

The authors recommend the US reevaluate past third-party deals suggested by non-US actors between Iran and the West:

]]>Iran has developed the capability to enrich uranium to 20 percent and has explored aspects of weaponization. The most recent IAEA report shows that Iran’s enrichment capability is increasingly diversified and robust. Faced with these new facts on the ground, the United States will have to rethink making an agreement with Iran. The alternatives are worse. Military strikes will effectively remove the domestic constraints on the effort to develop nuclear weapons. Iran’s weapons program will go from dormant to overdrive.

Two years ago, Iran agreed to a Brazilian-Turkish fuel-swap proposal under which Iran could develop nuclear power without accumulating raw material for nuclear weapons. Last year, Russia put forth a plan imposing a number of restrictions on Iranian enrichment and facilitating more intrusive IAEA inspections. Neither proposal was supported by the United States, as the Obama administration’s top priority was to intensify international pressure on Tehran. Now, given Iran’s progress toward building the bomb, any new proposal should include an intrusive monitoring system with an early-warning mechanism inside Iran’s nuclear establishment. Such a requirement would help prevent a breakout program, as Iran would recognize that evidence of such activities would lead to military strikes and additional severe economic sanctions. The agreement would also have to be accompanied with a list of clearly defined steps that Iran could take to achieve the lifting of sanctions.