Readers who recall that four years ago a new US President seemed eager to defuse the West’s quarrel with Iran over its nuclear activities may wonder why we are all still waiting for white smoke. I am not sure I know the answer, but I have a hunch it has something to [...]]]>

Readers who recall that four years ago a new US President seemed eager to defuse the West’s quarrel with Iran over its nuclear activities may wonder why we are all still waiting for white smoke. I am not sure I know the answer, but I have a hunch it has something to do with a lack of realism on one side and a profound mistrust on the other.

The lack of realism is a Western failing. The US and the two European states, France and the UK, that still have the most influence on the EU’s Iran policy, ten years after the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) first reported certain Iranian failures (long since corrected) to comply with nuclear safeguards obligations, are still reluctant to concede Iran’s right to possess a capacity to enrich uranium.

These Western powers know that the treaty which governs the use of nuclear technology for peaceful purposes, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), does not prohibit the acquisition of uranium enrichment technology by the treaty’s Non-Nuclear-Weapon States (NNWS).

They know that several NNWS (Germany, the Netherlands, Japan, Brazil, Argentina, and South Africa) already possess this technology.

They know that the framers of the treaty envisaged that the monitoring of enrichment plants by IAEA inspectors would provide the UN Security Council with timely notice of any move by an NNWS to divert enriched uranium to the production of nuclear weapons.

Nonetheless, they cannot bring themselves to tell Iran they accept that Iran, as a NNWS party to the NPT, is entitled to enrich uranium, provided it does so for peaceful purposes, under IAEA supervision, and does not seek to divert any of the material produced.

One of the reasons for this goes back a long way. When India, a non-party to the NPT, detonated a nuclear device in 1974, US officials decided that it had been a mistake to produce a treaty, the NPT, which did not prohibit the acquisition of two dual-use technologies (so-called because they can be used either for peaceful or for military purposes) by NNWS.

The existence of a non-sequitur in their reasoning, since India was not a party to the NPT, seems not to have occurred to them. They set about persuading other states that were capable of supplying these technologies (uranium enrichment and the reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel) to withhold them from NNWS.

This could be defended, of course, on prudential grounds. However, it caused resentment among the NNWS who felt that their side of the NPT bargain was being eroded surreptitiously; ultimately, like all forms of prohibition, it was short-sighted, because it encouraged the development of a black market and enhanced the risk of clandestine programmes, unsupervised by the IAEA.

Denying Iran the right to enrich uranium, and trying to deprive Iran of technology that it had developed indigenously, (albeit with help from the black market), seemed more than prudential in 2003. It seemed a necessity, because at the time there were good reasons to think that Iran had a nuclear weapons programme.

Nevertheless, by 2008, the US intelligence community had concluded that Iran abandoned that programme in late 2003 and would only resume it if the benefits of doing so outweighed the costs.

Despite that and subsequent similar findings, this prohibitionist mind-set is still prevalent in Washington, Paris and London. It is one explanation for a lack of progress since President Obama first stretched out the hand of friendship four years ago.

Another explanation is Israel. Israel shares with North Korea, Pakistan and India the distinction of being one of only four states that do not adhere to the NPT. It nonetheless enjoys considerable influence over US, French and British nuclear non-proliferation policies. Israeli ministers are deeply opposed to Iran possessing a uranium enrichment capability.

They may or may not believe what they frequently claim: that Iran will use its enrichment plants to produce fissile material and will use that fissile material to attack Israel with nuclear weapons, directly or through Hezbollah. In reality, few outside Israel believe this, and many inside are sceptical. However, they do not want Israel’s room for military manoeuvre to be reduced by the existence of a south-west Asian state that could choose to withdraw from the NPT and seek to deter certain Israeli actions by threatening a nuclear response.

A third explanation is Saudi Arabia. Leading Saudis are as opposed as Israeli ministers to Iran retaining an enrichment capability. They are less inclined than Israelis to talk of this capability as posing an “existential” threat; but they share the Israeli fear that it will erode their options in the region. They also fear that it will enhance the regional prestige of their main political rival, an intolerable prospect – all the more so now that Iran and Saudi-Arabia are engaged in a proxy war in Syria that seems increasingly likely to re-ignite sectarian conflict in Iraq.

Finally, there remains strong hostility to Iran in some US quarters, notably Congress. This makes it difficult for any US administration to adopt a realistic policy of accepting Iran’s right to enrich uranium, relying on IAEA safeguards for timely detection of any Iranian violation of its NPT obligations, and minimising through intelligent diplomacy the risk of Iran’s leaders deciding to abuse their enrichment capability.

On the Iranian side, the lack of trust in the US’ good faith has become increasingly apparent. It is in fact a hall-mark of Iran’s supreme decision-taker, Ayatollah Khamenei. One hears of it from Iranian diplomats. The Ayatollah himself barely conceals it in some of his public statements.

As recently as March 20, marking the Persian New Year, he said: “I am not optimistic about talks [with the US]. Why? Because our past experiences show that talks for the American officials do not mean for us to sit down and reach a logical solution [...] What they mean by talks is that we sit down and talk until Iran accepts their viewpoint.”

This distrust has militated against progress in nuclear talks by making Iran’s negotiators ultra-cautious. They have been looking for signs of a change in US attitudes – a readiness to engage sincerely in a genuine give-and-take – and have held back when, to their minds, those signs have not been apparent.

Instead of volunteering measures that might lead the West to have more confidence in the findings of Western intelligence agencies (that Iran is not currently intent on acquiring nuclear weapons), the Iranian side has camped on demanding that its rights be recognised and nuclear-related sanctions lifted.

Unfortunately, this distrust has been fuelled by the Western tactic of relying on sanctions to coerce Iran into negotiating. Ironically, sanctions have had the opposite effect. They have sowed doubts in Ayatollah Khamenei’s mind about the West’s real intentions, and they have augmented his reluctance to take any risks to achieve a deal.

Compounding that counter-productive effect, Western negotiators have been reluctant to offer any serious sanctions relief in return for the concessions they have asked of Iran, whenever talks have taken place. One Iranian diplomat put it this way: “They ask for the moon, and offer peanuts.”

Here part of the problem is a continuing Western hope, despite all experience to date, that unbearable pressure will induce Iran to cut a deal on the West’s unrealistic (and unbalanced) terms.

Another part is ministerial pride in having persuaded the UN Security Council, the EU Council of Ministers, and several Asian states to accept a sanctions regime that is causing hardship among ordinary Iranians (but from which Iran’s elites are benefitting because of their privileged access to foreign exchange and their control of smuggling networks). It sometimes seems as though causing hardship has ceased to be a means to an end; it has become an achievement to be paraded, a mark of ministerial success.

Many of the factors listed in the preceding paragraphs have been visible during the latest round of talks between the US and EU (plus Russia and China), which took place in Almaty, Kazakhstan, on April 5 and 6, 2013.

According to a draft of the proposal to be presented to Iran which Scott Peterson described in The Christian Science Monitor on April 4, the US and EU demanded:

- the suspension of all enrichment above the level needed to produce fuel for power reactors [5% or less];

- the conversion of Iran’s stock of 20% U235 into fuel for research reactors, or its export, or its dilution;

- the transformation of the well-protected Fordow enrichment plant to a state of reduced readiness [for operations] without dismantlement;

- the acceptance of enhanced monitoring of Iranian facilities by the IAEA, including the installation of cameras at Fordow to provide continuous real-time surveillance of the plant.

In exchange, the US and EU offered to suspend sanctions on gold and precious metals, and the export of petrochemicals, once the IAEA confirmed implementation of all the above measures. They also offered civilian nuclear cooperation, and IAEA technical help with the acquisition of a modern research reactor, safety measures and the supply of isotopes for nuclear medicine. In addition, the US would approve the export of parts for the safety-related repair of Iran’s aging fleet of US-made commercial aircraft.

Finally, the proposal stressed that additional confidence-building steps taken by Iran would yield corresponding steps from the P5+1, including proportionate

relief of oil sanctions.

The initial Iranian response on April 5 seems to have been less than wholeheartedly enthusiastic. On the first day of the talks they irritated the US and EU negotiators by failing to react directly to the US/EU proposals. Instead they reiterated their demand for the recognition of Iran’s rights and the lifting of sanctions as preconditions for any short-term confidence building curbs on their 20% enrichment activities.

On the second day, however, according to Laura Rozen, writing for Al Monitor on April 6, and quoting Western participants in the talks, Iran “pivoted to arguing for a better deal.” The Iranian team started to make clear what they would require in return for curbing Iran’s 20% activities, notably the lifting of “all unilateral sanctions.” These mainly comprise the oil and financial sanctions imposed in 2012.

“I’ve never seen anything quite like it,” a US diplomat said. “There was intensive dialogue on key issues at the core of [the proposed confidence building measures].”

Will that pivot be a turning-point? The latest proposal clearly falls far short of what Iran seeks by way of clarity that ultimately the US and EU can accept Iran retaining a dual-use enrichment capability, and by way of relief from oil and financial sanctions. There has been no sign that the US and EU can bring themselves to offer significant movement on either of these points.

Yet, a scintilla of hope can be drawn from the fact that on April 6 there may have been the beginnings of a haggle. If both sides can resume their talks in that haggling mode, progress may finally be achievable. Haggling is central to any good negotiation. Until now it has been sorely lacking in dealings with Iran under President Obama.

This article was originally published by the Fair Observer on April 10th, 2013.

]]>by Charles Naas

The second round of talks in Almaty, Kazakhstan between the P5+1 (the US, UK, France, Russia, China and Germany) and Iran ended just about where they started — no advance from the March talks and the glimmer of hope that perhaps some kind of momentum could be established. Unlike Almaty [...]]]>

by Charles Naas

The second round of talks in Almaty, Kazakhstan between the P5+1 (the US, UK, France, Russia, China and Germany) and Iran ended just about where they started — no advance from the March talks and the glimmer of hope that perhaps some kind of momentum could be established. Unlike Almaty I, no date was set for a continuation of the negotiations. Western diplomats offered mixed messages about what happened during the two lengthy sessions. In fact, there should be no mystery about the sick snail pace of the negotiations The two sides are not on the same page and are talking past each other. As long as this continues, an understanding will be highly unlikely.

The P5+1 are focused on an agreement that is limited to the nuclear issue and as restrictive as possible on Iran’s program in the future. When negotiations began during the Bush administration, the US demanded that Iran cease all uranium enrichment which Iran was producing at the reactor fuel level of 3.5-4% as a condition for the talks. That was a non-starter and quickly put aside when Iran decided to enrich uranium to 20% at its Fordow facility, which is buried deeply in a mountain near the holy city of Qom. Twenty percent enriched uranium can be enriched to explosive level in as quickly as 3 months or less if Iran decides to race for a bomb. Fordow has, therefore, become the central concern of the P5+1, though the revised proposal reportedly softened the demand for its total closure. It’s unclear whether the 6 powers have explicitly or implicitly recognized Iran’s right to enrich uranium to fuel its future power reactors. The Six have reportedly offered small-scale sanctions relief and the sale of selective goods to Iran, but otherwise continue to take a hard line on keeping the talks tightly tied to nuclear affairs.

It has become clear that Iran’s position is based on the principle that it’s a fully independent and equal member of the world community and will go to extreme lengths to avoid accepting a lesser status. Call it Iranian pride, self respect, history and ambitions for the future. The two times in modern history that Iran was forced to accept foreign dictate — the 1907 Russian-UK Agreement on spheres of influence and the World War II occupation — still rankle, as does the overthrow of Prime Minister Mohamed Mossadegh in 1953. In line with this principle, Iran insists that it has all the rights of the Nuclear Non- Proliferation Treaty (NPT) — to which it was an early member — and that this includes the full fuel-cycle from enrichment to reprocessing of spent fuel.

Iran has been consistent. In the mid-1970s, the US and Iran engaged in lengthy talks about a new treaty to permit US cooperation on the sale of reactors to the Shah’s very ambitious power reactor program. Iran’s negotiators adamantly assumed the same position that they operate on now: Iran should be regarded and treated as the proud and sovereign nation that it is. Iran has, therefore, rejected any restrictions on its civilian power reactor program but has apparently indicated some willingness to cooperate on the output of Fordow. But this was likely expressed in an ambiguous manner and remains insufficient for the P5+1. The Six’s offer of slight sanctions relief has also been implicitly spurned.

By its mere presence at the meetings, Iran has accepted the premise that its nuclear program is both important and contentious, but its objectives are far-reaching in contrast to the Six’s aim of restricting discussions to nuclear affairs. Iran will not move far, if at all, without significant sanctions relief, and, as a final step, the conclusion of all UN and other sanctions against it. Beyond these measurable aims, Iran has indicated that negotiations should be expanded to include an examination of the power realities within the region and on how Iran is perceived by major powers. The more ambitious Iranians who are involved with the country’s international concerns see Iran’s long history; its central geographic position; the size of its population; its realizable great wealth from petroleum; and the potential from its rapidly growing, educated population (particularly in the sciences), as inevitably leading it to a form of regional hegemony. These negotiators have carefully and with some subtlety melded their objectives.

The strenuous diplomatic process with Iran has been taking place in the background of more than thirty years of enmity and decades of steadily increasingly, painful sanctions. American threats of “all options are on the table”, cyber warfare directed at Iran’s enrichment facilities and substantial US and allied military forces in the Gulf, have added to ongoing tension and feed Iran’s concern that we really are aiming for regime change. Our strong ties with Israel, which compel us to support the notion that an Iranian ability to build a nuclear explosive poses an existential threat, also amplifies Iran’s distrust.

On the other hand, the US and others have alleged that Iran is a major supporter of international terrorism and that it has the intention of at least getting to the point where it could rapidly create a nuclear weapon. Iranian denials of such plans, and Leader Ali Khamenei’s Fatwa, have had no resonance in the Obama administration. Add to this an emerging friction in current political alliances within the Middle East. Iran — and the Russians – support the other Shi’a states, Syria and Iraq, and parties such as Hezbollah. The US, UK, France and Germany have sided with the Arab Sunni monarchies, the Syrian rebels and Israel.

At this point, neither side has moved significantly from its opening position. Unless both sides give their negotiators new and more flexible instructions, movement towards an agreement is highly unlikely. Meaningful change is domestically difficult, but it may be worth continuing talks simply to have an established site for future exchanges as problems arise. So far, perhaps the main positive result has been the seemingly successful process of breaking ice between Iran and the US.

]]>by Djavad Salehi-Isfahani

The latest round of talks between the P5+1 (the US, Russia, China, Britain, France, and Germany) and Iran in Kazakhstan concluded on Saturday without any tangible progress. While details of the reciprocal offers remain unclear, what we have learned indicates that neither side is in any particular hurry [...]]]>

by Djavad Salehi-Isfahani

The latest round of talks between the P5+1 (the US, Russia, China, Britain, France, and Germany) and Iran in Kazakhstan concluded on Saturday without any tangible progress. While details of the reciprocal offers remain unclear, what we have learned indicates that neither side is in any particular hurry to conclude the lengthy negotiations. In the meantime international sanctions, which have plunged Iran’s economy into its deepest crisis since the war with Iraq, will remain in force and may even be tightened. An important question now is whether the delay in resolving the crisis favors Iran or its Western foes, and the answer has to do in part with what one believes is happening to Iran’s economy.

Just before the talks restarted, a report in the New York Times entitled “Double-Digit Inflation Worsens in Iran” may have strengthened the belief of those in the US who think that time is on their side. If inflation — the most obvious, if not the most painful, effect of sanctions — has gotten worse for the sixth month in a row, then waiting a few more months might weaken Iran’s position. The article was based on new data released by Iran’s Statistical Center, which, when looked at more closely actually shows that inflation has been up and down in the last six months, falling as many times as it went up, though prices go only up (see a detailed graph of monthly inflation rates here). The persistence of high inflation has as much to do with sanctions as with Mr. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s insistence on making good before he leaves office and ahead of the June presidential election by pushing ahead with his unfunded (and therefore inflationary) promises of cash transfers and low-cost housing.

Iranian officials who were last year denying the impact of sanctions now praise them for helping Iran wean its economy from oil. Last month, Iran’s Minister of Economy, Shamseddin Hosseini, said that “Thanks to the sanctions [imposed] by enemies, a historical dream of Iran is being realized as the oil revenues’ share in the administration of the country’s affairs has been reduced.” The Minister for Industry, Mining and Commerce also added a humbling note, “What we had been unable to achieve on our own, sanctions have done for us.” He was referring to the huge inflow of cheap imports paid for by the oil revenues over which he has presided since 2009.

As these officials have discovered lately, oil money can stock the kitchens and living rooms of the average family while keeping their educated son or daughter out of a job. While imports increased eightfold over the last ten years, many local producers in agriculture or industry have either shut down or increased the import content of their production. Either way, jobs have been lost. Between 2006 and 2011, census figures show that Iran’s economy created zero new jobs, as the working age population increased by 3.5 million.

As I have argued before, the devaluation of the rial, which many saw as the reason why Iran restarted negotiating, is actually a reason why it may not be in such a hurry to resume its oil exports. A study last week that was surprising for its source — the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, which has always pushed for tougher sanctions on Iran — admitted that Iran is doing a good job of adjusting to reduced oil revenues. It shows how the balance of trade in non-oil items is improving and how the government budget is becoming less dependent on oil.

But adjusting to the financial sanctions is an entirely different story. After being cut off from the international banking system and with limited access to global markets, Iran is finding it extremely hard to turn its import-dependent economy around. If Iran could choose which of the two sets of sanctions to lose first, oil or financial, it would definitely be the latter.

]]>via IPS News

Since Barack Obama became president of the United States, messages marking the Iranian New Year – Norouz – celebrated at the onset of spring have become yearly affairs. So have responses given by Iran’s Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei from the city of Mashhad where he makes a [...]]]>

via IPS News

Since Barack Obama became president of the United States, messages marking the Iranian New Year – Norouz – celebrated at the onset of spring have become yearly affairs. So have responses given by Iran’s Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei from the city of Mashhad where he makes a yearly pilgrimage to visit the shrine of Shi’i Islam’s eighth imam, Imam Reza.

This year, like the first year of Obama’s presidency, the two leaders’ public messages had added significance because of the positive signals broadcast by both sides after Iran and the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council plus Germany met in Almaty, Kazakhstan in March. The second meeting is slotted to occur Apr. 5-6.

Considering that the exchanged messages came in the midst of ongoing talks, a degree of softened language and the abandonment of threats was expected. In his first Norouz speech in 2009, when both sides were getting ready to embark on serious talks, Obama said that his administration was committed to diplomacy and a process that “will not be advanced by threats” and is “honest and grounded in mutual respect”.

This time, however, his message was laced with threats and promises of rewards if Iranian leaders behaved well, eliciting Khamenei’s disdainful response, and revealing yet again how intractable – and dangerous – the conflict between Iran and the United States has become.

The dueling exchanges also revealed the rhetorical game both sides are playing for the hearts and minds of the Iranian people, who are caught in the crossfire of policies in which they have very little input despite the very serious impact these policies have had on their economic well-being.

Reciting Persian poetry and touting the greatness of Iran’s civilisation and culture, President Obama once again suggested that the United States is ready to reach a solution that gives “Iran access to peaceful nuclear energy while resolving once and for all the serious questions that the world has about the true nature of the Iranian nuclear programme.”

But this general offer – which remained unclear on the key question of whether the United States is willing to formally recognise Iran’s right to enrich uranium on its soil – was also framed within an explicit threat that if the “Iranian government continues down its current path, it will further isolate Iran.”

In other words, the Iranian leaders can choose “a better path” which Obama insisted was for the sake of the Iranian people for whom there is no good reason “to be denied the opportunities enjoyed by people in other countries, just as Iranians deserve the same freedoms and rights as people everywhere.”

Although Iran’s isolation was acknowledged, President Obama’s words were carefully chosen not to mention the fact that it is the United States that has endeavored to impose a ferocious sanctions regime on Iran which, in his words, “deny opportunity enjoyed by people of other countries.”

In the Norouz greeting that came after a tough year of hardship, highlighted by a 40-percent drop in Iran’s oil exports, Obama’s implicit message was that the Iranian people should not blame the United States as the source of their economic difficulties but rather their own government’s choice in refusing the demands of the “international community”.

Viewed through the eyes of the Iranian leadership, the aggressiveness of such a posture was obvious, particularly since two days later, standing next to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel, the U.S. president set aside his soft language and once again reiterated that as far as Iran is concerned “all options are on the table.”

In other words, if the Iranian leaders do not abandon their current path, the people of Iran will not only continue to be collectively punished through broad-based sanctions and denial of opportunities, they may also be subject to military attacks.

Not surprisingly, the response from Ayatollah Khamenei was calibrated to counter President Obama’s threats hidden in the language of respect for Iranian culture and people. Khamenei also showed his conciliatory side by stating that he does not oppose even bilateral talks with the United States, but added the caveat that he is not optimistic about their results. Why?

“Because our past experiences show that in the logic of the American gentlemen, negotiation does not mean sitting down together to try to reach a rational solution,” Khamenei said. “This is not what they mean by negotiation. What they mean is that we should sit down together and talk so that Iran accepts their views. The goal has been announced in advance: Iran must accept their view.”

Highlighting a clear disconnect between what Obama says to different audiences, Ayatollah Khamenei went to the heart of the problem President Obama has in convincing the Iranian people that he has their interest in mind when talking to them. Khamenei reminded his Iranian audience that “in his official addresses, the American president speaks about Iran’s economic problems as if he is speaking about his victories.”

He pointed to the announced intent of sanctions to “cripple” Iran by “the incompetent lady who was responsible for America’s foreign policy”, an apparent reference to former secretary of state Hillary Clinton.

Khamenei’s response also singled out the United States as Iran’s number one enemy and “main centre of conspiracies against the Iranian nation”. He did acknowledge the help the U.S. gets from other Western countries and Israel but dismissed the latter as “too small to be considered among the frontline enemies of the Iranian nation”.

Along the same lines, Khamenei was also dismissive of Obama’s claim to speak for the international community. “The international community is no way interested in enmity with Iranian or Islamic Iran,” Khamenei said.

Despite differences, however, Khamenei speech had one key point in common with Obama’s message. Both leaders were ready to heap praise on the Iranian people; one did so for their “great and celebrated culture” and the other for their resistance and “high capacity and power to turn threats into opportunities”.

Heaping praise, however, cannot hide the fact that the most likely victims of the conflict between the governments of the two countries are the ones that have no input in the decisions made in either country. Both speeches made clear that, caught in the rhetorical crossfire, the people of Iran are subjects to be wooed and courted but whose economic welfare is not of much concern.

Photo Credit: “Kamshots” Flickr.

]]>by Jasmin Ramsey

Ahead of the technical-level nuclear talks that will take place in Istanbul on March 18 and the top-level talks that will be held in early April, Farideh Farhi, an Independent Scholar at the University of Hawaii and Lobe Log contributor, offers context and insight [...]]]>

by Jasmin Ramsey

Ahead of the technical-level nuclear talks that will take place in Istanbul on March 18 and the top-level talks that will be held in early April, Farideh Farhi, an Independent Scholar at the University of Hawaii and Lobe Log contributor, offers context and insight into what can reasonably be expected in terms of results.

Q): Considering the cautious optimism that was expressed by the Iranians after the Almaty talks (February 26-27), is there a better chance for a breakthrough during the March/April meetings?

Farideh Farhi: It is too soon to think of breakthrough at this point. But the decision on the part of Iran’s negotiating team to portray the slight move on the part of the United States [to offer slight sanctions relief] as a turning point, has given the leadership in Tehran room to sell an initial confidence-building measure in the next couple of months as a “win-win situation,” something the Iranians have always claimed to be interested in. Having room to maneuver domestically, however, does not necessarily mean that it will happen. In the next couple of months we just have to wait and see the extent to which opponents of any kind of deal in both Tehran and Washington will be able to prevent the optimism that’s been expressed from turning into a process of give and take.

At this point, though, it is noteworthy that the first signs of opposition to what happened in Almaty occurred in Washington and not Tehran (see this Washington Post editorial.) In Iran, the questioning that has since emerged is about whether the positive portrayal of a US shift, for example by Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Salehi, is justified by an actual shift in Almaty, which some deem as not sufficient to warrant an agreement; at least not yet.

Q): CNN reported on March 2 that Iran was open to direct talks, but Iran has made similar statements before and you’ve pointed out that direct talks have already taken place back in October 2009. What happened during that meeting?

Farideh Farhi: I have written about what happened then here, but in short, during the October 2009 Geneva meeting, which occurred while Iran was in the midst of post-election turmoil, hopes were raised by the Saeed Jalili-led nuclear team, after he met with US negotiator William Burns, that a breakthrough had happened and the US had accepted Iran’s right to enrich uranium in exchange for the transfer of uranium out of Iran (later to be returned to Iran in the transformed form of fuel for the Tehran Research Reactor). But Iran’s tumultuous post-election environment, combined with a lack of transparency regarding the agreement’s details, led to opposition across the political spectrum. Rightly or wrongly, there was a sense in the public that the hard-line power leaders were making a behind-the-scenes-deal with outside powers in order to continue repression at home. Eventually the inability of both Jalili and President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to convince others in Iran that the agreement included an explicit acceptance of Iran’s enrichment program led to Leader Ali Khamenei’s withdrawal of support for the agreement.

Q: Why do you think the administration is so focused on direct talks right now while Congress seems to be operating on a completely different beat, and what needs to happen for direct talks to happen again.

Farideh Farhi: The insistence on direct talks, I assume, is about receiving a signal from the Leader that he is interested in resolving the nuclear issue. The problem is that there is also a lack of trust on his side and he needs to be assured that the United States is interested in a process of give and take. He, along with quite a few others in Iran, need to be convinced that bilateral talks are not a trap intended to reignite the international consensus for the further squeezing of Iran, which the Obama Administration has been unable to sustain due to Russian and Chinese refusal to buy in at the United Nations.

In addition, many in Iran, rightly or wrongly, have come to believe that the US interest in direct talks is only about exacting concessions from Iran or serving its own interests without any attention to Iran’s needs and interests. Experiences such as Iran’s engagement with the US over Afghanistan in 2001, and the three rounds of talk over Iraq in 2006-07, have given the impression that there is no equivalency between what the US demands and what it’s willing to offer. In Iraq, for instance, the US wanted Iran’s help for the resolution of everyday security challenges that the US was facing without acknowledging that Iran also has interests in shaping the political direction of Iraq. There are other examples but the end result has always been Tehran’s increased caution regarding direct dealings with the US.

As of now, the two countries are still far from finding a common language to talk to each other with. Washington is still focused on the resolution of immediate issues of concern, be it Iran’s nuclear program or figuring out a way of getting Iran’s help — or at least reducing Iran’s incentive to create trouble — as it tries to untangle itself from Afghanistan. Tehran, on the other hand, is focused on longer-term strategic issues and the consolidation of its role in the region. For Tehran to enter into a direct conversation with the US, it has to be convinced that it will also get something tangible out of it.

Q: What needs to happen on both sides to increase the chances for progress during the March/April talks, and if you believe that nothing will happen on the Iranian side before the election, what needs to happen generally.

I fall into the category of people who think that something can happen before the election. The fact that the Iranians agreed to have technical talks so soon confirms my belief. The unambiguous signal from Tehran is that the nuclear issue is a systemic matter and will not be affected by the result of the election. Meanwhile, the decision by the United States to shift a bit before the election also signals to Iran’s leadership that it’s not betting on or hoping for the victory of any particular candidate in the election. If it’s sustained, this move, unlike the dynamics we saw during the 2009 election, will take the question of potential talks with the US out of the Iranian electoral equation because some form of them are already taking place.

What needs to happen in the next few months is a demonstration on the part of Tehran that it’s willing to suspend part of its enrichment program in exchange for the suspension of some sanctions on the part of the United States and Europe. Neither of these suspensions need to be consequential or major in terms of broader demands that both sides have on each other. But the acceptance of a mini-step as a first step is by itself a sign that a process — based on a more realistic understanding and expectation of what can be given and taken from both sides — has begun. If this happens — given the contentious dynamics in both countries and ferocious opposition by a number of regional players to any kind of talks between Iran and the United States — it’s a very big deal, even it it continues to occur within the P5+1 frame.

]]>A new report released by the International Crisis Group this week examines the efficacy and unintended consequences of sanctions on Iran and suggests steps that can be taken during the diplomatic process to unwind them and mitigate their humanitarian consequences while addressing the nuclear issue more effectively. “The [...]]]>

A new

report released by the International Crisis Group this week examines the efficacy and unintended consequences of sanctions on Iran and suggests steps that can be taken during the diplomatic process to unwind them and mitigate their humanitarian consequences while addressing the nuclear issue more effectively. “The Iranian case is a study in the irresistible appeal of sanctions, and of how, over time, means tend to morph into ends”, says Ali Vaez, Crisis Group’s Senior Analyst for Iran. “In the absence of any visible shift in Tehran’s political calculus, it is difficult to measure their impact through any metric other than the quantity and severity of the sanctions themselves”.I’m still making my way through it, but it’s already clear that this is one of those don’t-miss reports for Iran-watchers and those who are interested in US-Iran relations. I’ve reproduced the recommendations from the executive summary below, beginning with the most important issue related to the sanctions regime — the healthcare crisis in Iran — which Lobe Log contributor Siamak Namazi wrote about today in the New York Times:

RECOMMENDATIONS

To address the healthcare crisis in Iran

To the government of Iran:

1. Streamline currency allocation, licensing and customs procedures for medical imports.

To the government of the United States and the European Union:

2. Provide clear guidelines to financial institutions indicating that humanitarian trade is permissible and will not be punished.

3. Consider allowing an international agency to play the role of intermediary for procuring specialised medicine for Iran.

To sustain nuclear diplomacy and bolster chances of success

To the P5+1 [permanent UN Security Council members and Germany] and the government of Iran:

4. Agree to hold intensive, continuous, technical-level negotiations to achieve a step-by-step agreement and, to that end, consider establishing a Vienna- or Istanbul-based contact group for regular interaction.

5. Recognise both Iran’s right in principle to enrich uranium for peaceful purposes on its soil and its obligation to provide strong guarantees that the program will remain peaceful.

To the governments of Iran and the United States:

6. Conduct bilateral negotiations on the margins of the P5+1 meetings or parallel to them.

To address the immediate issue of 20 per cent uranium enrichment

To the P5+1 and the government of Iran:

7. Seek agreement on a package pursuant to which:

a) Iran would suspend its uranium enrichment at 20 per cent level for an initial period of 180 days and convert its existing stockpile of 20 per cent enriched uranium to nuclear fuel rods; and

b) P5+1 members would provide Iran with medical isotopes; freeze the imposition of any new sanctions; waive or suspend some existing sanctions for an initial period of 180 days (eg, the ban on the sale of precious and semi-finished metals to Iran or the prohibition on repatriating revenues from Iranian oil sales); and release some of Iran’s frozen assets.

To address the issue of Fordow

To the P5+1 and the government of Iran:

8. Seek agreement on a package pursuant to which:

a) Iran would refrain from installing more sophisticated Centrifuges at Fordow and implement additional transparency measures, such as using the facility exclusively for research and development purposes and allowing in-house International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) resident inspectors or installing live-stream remote camera surveillance; and

b) P5+1 members would suspend sanctions affecting Iran’s petro-chemical sector or permit Iran’s oil customers to maintain existing levels of petroleum imports.

To reach a longer-term agreement

To the P5+1 and the government of Iran:

9. Seek agreement on a package pursuant to which:

a) Iran would limit the volume of stockpiled 5 per cent enriched uranium, with any amount in excess to be converted into fuel rods; ratify the IAEA’s Additional Protocol and implement Code 3.1; and resolve outstanding issues with the IAEA; and

b) P5+1 members would provide Iran with modern nuclear fuel manufacturing technologies; roll back financial restrictions; and lift sanctions imposed on oil exports; the P5 would submit and sponsor a new UN Security Council resolution removing international sanctions once issues with the IAEA have been resolved.

To rationalise future resort to sanctions on third countries

To the U.S. and European Union:

10. Consider setting up an independent mechanism to closely assess, monitor and re-evaluate the social and economic consequences of sanctions both before and during implementation to avoid unintended effects, harming the general public or being trapped in a dynamic of escalatory punitive measures.

11. Avoid where possible imposition of multi-purpose sanctions lacking a single strategic objective and exit strategy.

]]>When Iranian officials sit down at the negotiating table in Almaty with representatives from six international powers, Kazakhstan will gain kudos that will burnish its international diplomatic image and raise the prestige of President Nursultan Nazarbayev. The event may also encourage the United States and European Union members to restrain criticism of [...]]]>

When Iranian officials sit down at the negotiating table in Almaty with representatives from six international powers, Kazakhstan will gain kudos that will burnish its international diplomatic image and raise the prestige of President Nursultan Nazarbayev. The event may also encourage the United States and European Union members to restrain criticism of Kazakhstan’s democratization shortcomings. “Kazakhstan has long tried to shape the state’s image as an intermediary in various conflicts and offer a platform for discussion of regional problems,” said political analyst Dosym Satpayev, director of the Kazakhstan Risks Assessment Group think-tank.

Catherine Ashton, the European Union foreign policy chief who heads the six-nation group negotiating with Iran, confirmed in an e-mailed statement on February 5 that talks would take place in Almaty on February 26. She said the negotiations were agreed on between Helga Schmid, the European External Action Service’s deputy secretary general, and Ali Bagheri, deputy secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council. Ashton also thanked Kazakhstan’s government “for its generous offer to host the talks.”

The confirmation came after Tehran had signaled two days earlier that it was ready to talk to the six-nation group – comprised of Russia, the United States, China, Britain, France and Germany — after an eight-month hiatus. Speaking in Munich on February 3, Iranian Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Salehi first disclosed the “good news” that Kazakhstan would be hosting a meeting in late February.

Nazarbayev’s administration has on several occasions offered to act as host for talks on Iran’s nuclear ambitions. On February 4, Altay Abibullayev, a spokesperson for the Kazakhstani president’s Central Communications Service, reiterated the administration’s eagerness to lend a helping hand. “We as the receiving side will make all efforts to create the most favorable conditions for successfully holding these talks in Kazakhstan,” he said.

Hosting the Iran nuclear talks dovetails with Kazakhstan’s long-standing efforts to become a global diplomatic player. In connection with those endeavors, Kazakhstan chaired the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe in 2010 and is current lobbying for a temporary seat on the United Nations Security Council in 2016.

When it comes to agreement on the Iranian nuclear question, Astana’s influence over the negotiations will be limited, Satpayev pointed out. “There is Kazakhstan’s desire to present itself as an intermediary, and then there are the [real] possibilities [of what the talks can achieve],” he said. “It all depends on Iran’s political will.”

The discussions on Iran’s nuclear program have been deadlocked since negotiations in Moscow last June. The six-nation group is pressing Iran to comply with UN Security Council resolutions to end uranium enrichment and close an underground enrichment facility. The international community also wants Iran to hand over stockpiles of uranium already enriched to the level of 20 percent (a critical stage in the nuclear bomb-making process) for international safe-keeping. Tehran insists its program is for peaceful purposes, and wants international sanctions lifted.

Kazakhstan is a fitting host for the Iranian nuclear discussions, given its own history. The country voluntarily gave up the nuclear weapons arsenal it inherited following the 1991 Soviet collapse. It is also home to the mothballed Soviet nuclear testing site at Semipalatinsk that has left a devastating environmental and health legacy on the country.

Nazarbayev has sought to play a leading international role in anti-proliferation efforts. In an opinion piece published by the New York Times in March 2012, Nazarbayev asserted that Kazakhstani authorities “have worked tirelessly to encourage other countries to follow our lead and build a world in which the threat of nuclear weapons belongs to history.”

Nazarbayev went on to address the Iranian nuclear question directly, urging Tehran “to learn from our [Kazakhstan’s] example” and opt for “building peaceful alliances and prosperity over fear and suspicion.”

In a bid to reduce proliferation risks, Kazakhstan has offered to host an international nuclear fuel bank under the auspices of the International Atomic Energy Agency that would give states access to low-enriched uranium for peaceful purposes. And the fuel bank offer has won plaudits from Washington: last fall former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton praised it, noting that “few countries can be compared to Kazakhstan in terms of its experience in non-proliferation.”

This suggests Washington sees Kazakhstan as an honest broker in nuclear talks involving Iran. Kazakhstan cultivates good relations with all the big powers, including the United States, Russia and China, and is viewed as a “more or less neutral state” to offer a platform for dialogue, Satpayev said.

Photo: A monument in to those who suffered during nuclear testing at Semipalitinsk serves as a reminder of Kazakhstan’s nuclear past. The country, which gave up its nuclear arsenal after the break-up of the Soviet Union, will host sensitive talks on Iran’s nuclear ambitions later this month. (Photo: David Trilling)

Sunday’s New York Times story that the US and Iran have agreed in principle to direct bilateral negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program provides opportunity for a more honest conversation on Iran than the presidential candidates have had so far. Well, at least this is my hope.

I know the NYT [...]]]>

Sunday’s New York Times story that the US and Iran have agreed in principle to direct bilateral negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program provides opportunity for a more honest conversation on Iran than the presidential candidates have had so far. Well, at least this is my hope.

Sunday’s New York Times story that the US and Iran have agreed in principle to direct bilateral negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program provides opportunity for a more honest conversation on Iran than the presidential candidates have had so far. Well, at least this is my hope.

I know the NYT report has already been rejected by the US and Iran. But the rejections on both sides have a similar quality. Despite the Iranian refusal to meet with the US in the talks that began in Istanbul last April, neither has rejected the possibility of bilateral talks as an outgrowth of the P5+1 process. And both have said that talks within the P5+1 frame will begin in late November (time and place to be determined). In any case, the P5+1 frame has increasingly become a venue dominated by US demands.

But the value of the NYT revelation or leak is not in the reporting of an agreement on a potential meeting but in the impact it may have on the nature of the conversation about Iran’s nuclear program. The reality is that the presidential race has so far managed to avoid the real Iran question. Certainly there has been grandstanding and threats. There was the frenzy over the need to set red line or deadline for Iran which was thankfully calmed — at least temporarily — by Prime Minister’s Benjamin Netanyahu’s inane performance at the UN.

The campaign has also been full of sounds bites regarding the seeming contrast between “having Israel’s back” and “not allowing daylight between Israel and the United States”. But there has been no conversation regarding the rapidly approaching decision time regarding Iran. No conversation regarding whether the United States, after years of offering what it knew would be refused, is willing to offer something that Iran can accept.

Everyone knows what the elements of the offer are: limits on levels of enrichment combined with a more robust inspection regime in exchange for calibrated reduction of some of the sanctions. There are many details to be worked out in difficult negotiations, but these details cannot even begin to be addressed without public acceptance of some enrichment in Iran or the acknowledgment of Iran’s proverbial “inalienable right.”

Why do I say that there is a rapidly approaching decision time for which direction to go in? Well, sanctions have worked to create economic havoc in Iran. No doubt both President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Leader Ali Khamenei are primarily responsible for the deteriorating conditions. But their responsibility lies not in their incompetence in managing the economy per se but in their miscalculation. Khamenei, in particular, suspected negotiations would not go anywhere (at least, this is what he keeps saying) but he failed to prepare the country for his publicized “resistance economy.”

A resistance economy cannot be created overnight; certainly not when the economic helm of the country is in the combined hands of a populist president who underestimated the force of sanctions and a cantankerous Parliament caught between the demands of higher ups and pressures from lobbies and constituencies.

Not that Khamenei does not want a deal. He does and the encounters of the past four years have exhibited his openness to talks whenever there was hope in or detection of a degree of flexibility in the US position. But these encounters have also shown that he perceives himself as standing at the helm of a highly contentious political terrain that demands addressing certain bottom lines for Iran.

With the draconian economic measures imposed on Iran in the past year, the same political terrain makes quite impossible the acceptance of a deal that does not bring about some immediate, palpable, even if small, relaxation of the sanctions regime.

Some would say that this is precisely why this is no time for flexibility on the part of the United States. It will be throwing a lifeline to Khamenei and “them,” whoever they are. Now that sanctions are working, going for the throat is the right thing to do, they say. In response to this argument, which is also prevalent among some in the Iranian Diaspora who yell hard, accusing any country negotiating with Iran of being a traitor to the cause of the Iranian people, I would say that they are not adequately aware of the social and ideological forces than can be mobilized inside Iran to maintain a defiant, albeit limping, country.

Unless Khamenei and company are given a way out of the mess they have taken Iran into (with some help from the US and company), chances are that we are heading into a war in the same way we headed to war in Iraq. A recent Foreign Affairs article by Ralf Ekeus, the former executive chairman of the UN special Commission on Iraq, and Malfrid-Braut hegghammer, is a good primer on how this could happen.

The reality is that the current sanctions regime does not constitute a stable situation. First, the instability (and instability is different from regime change as we are sadly learning in Syria) it might beget is a constant force for policy re-evaluation on all sides (other members of the P5+1 included). Second, maintaining sanctions require vigilance while egging on the sanctioned regime to become more risk-taking in trying to get around them. This is a formula for war and it will happen if a real effort at compromise is not made. Inflexibility will beget inflexibility.

An additional benefit from directing the conversation away from whether to attack Iran and how to sanction it further is the positive impact on the nuclear debate inside Iran. There is no doubt in my mind that the conversation that has focused on attacking or sanctioning Iran until it kneels or submits has had the effect of making the hardliners defiantly louder and silencing those pushing for the resolution of the “Amrika issue.”

The loudness of the defiant folks rests on a simple argument again articulated last week in no uncertain terms by Khamenei himself: America’s problem with Iran is not the nuclear issue and talks for the US are not intended to resolve the nuclear standoff; they are a means to extract surrender from Iran.

If Khamenei is not correct, then a clearer public articulation of the extent of compromises the United States may be contemplating in order to resolve the nuclear standoff can encourage a conversation inside Iran as well. My bet is that it will also empower those pushing for Iran to show a bit more flexibility in its bottom line.

]]>via IPS News

Iran has again offered to halt its enrichment of uranium to 20 percent, which the United States has identified as its highest priority in the nuclear talks, in return for easing sanctions against Iran, according to Iran’s permanent representative to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Ali Asghar [...]]]>

via IPS News

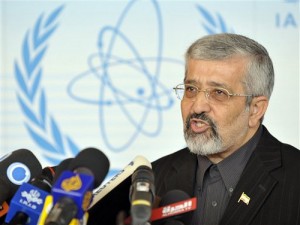

Iran has again offered to halt its enrichment of uranium to 20 percent, which the United States has identified as its highest priority in the nuclear talks, in return for easing sanctions against Iran, according to Iran’s permanent representative to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Iran has again offered to halt its enrichment of uranium to 20 percent, which the United States has identified as its highest priority in the nuclear talks, in return for easing sanctions against Iran, according to Iran’s permanent representative to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Ali Asghar Soltanieh, who has conducted Iran’s negotiations with the IAEA in Tehran and Vienna, revealed in an interview with IPS that Iran had made the offer at the meeting between EU Foreign Policy Chief Catherine Ashton and Iran’s leading nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili in Istanbul Sep. 19.

Soltanieh also revealed in the interview that IAEA officials had agreed last month to an Iranian demand that it be provided documents on the alleged Iranian activities related to nuclear weapons which Iran is being asked to explain, but that the concession had then been withdrawn.

“We are prepared to suspend enrichment to 20 percent, provided we find a reciprocal step compatible with it,” Soltanieh said, adding, “We said this in Istanbul.”

Soltanieh is the first Iranian official to go on record as saying Iran has proposed a deal that would end its 20-percent enrichment entirely, although it had been reported previously.

“If we do that,” Soltanieh said, “there shouldn’t be sanctions.”

Iran’s position in the two rounds of negotiations with the P5+1 – China, France, Germany, Russia, Britain, the United States and Germany – earlier this year was reported to have been that a significant easing of sanctions must be part of the bargain.

The United States and its allies in the P5+1 ruled out such a deal in the two rounds of negotiations in Istanbul and in Baghdad in May and June, demanding that Iran not only halt its enrichment to 20 percent but ship its entire stockpile of uranium enriched to that level out of the country and close down the Fordow enrichment facility entirely.

Even if Iran agreed to those far-reaching concessions the P5+1 nations offered no relief from sanctions.

Soltanieh repeated the past Iranian rejection of any deal involving the closure of Fordow.

“It’s impossible if they expect us to close Fordow,” Soltanieh said.

The U.S. justification for the demand for the closure of Fordow has been that it has been used for enriching uranium to the 20-percent level, which makes it much easier for Iran to continue enrichment to weapons grade levels.

But Soltanieh pointed to the conversion of half the stockpile to fuel plates for the Tehran Research Reactor, which was documented in the Aug. 30 IAEA report.

“The most important thing in the (IAEA) report,” Soltanieh said, was “a great percentage of 20-percent enriched uranium already converted to powder for the Tehran Research Reactor.”

That conversion to powder for fuel plates makes the uranium unavailable for reconversion to a form that could be enriched to weapons grade level.

Soltanieh suggested that the Iranian demonstration of the technical capability for such conversion, which apparently took the United States and other P5+1 governments by surprise, has rendered irrelevant the P5+1 demand to ship the entire stockpile of 20-percent enriched uranium out of the country.

“This capacity shows that we don’t need fuel from other countries,” said Soltanieh.

Iran began enriching uranium to 20 percent in 2010 after the United States made a virtually non-negotiable offer in 2009 to provide fuel plates for the Tehran Research Reactor in return for Iran’s shipping three-fourths of its low-enriched uranium stockpile out of the country and waiting for two years for the fuel plates.

The P5+1 demand for closure of the Fordow enrichment plant was also apparently based on the premise the facility was built exclusively for 20-percent enrichment. But Iran has officially informed the IAEA that it is for both enrichment to 20 percent and enrichment to 3.5 percent.

The 1,444 centrifuges installed at Fordow between March and August – but not connected to pipes, according to the Washington-based Institute for Science and International Security – could be used for either 20-percent enrichment or 3.5-percent enrichment, giving Iran additional leverage in future negotiations.

Soltanieh revealed that two senior IAEA officials had accepted a key Iranian demand in the most recent negotiating session last month on a “structured agreement” on Iranian cooperation on allegations of “possible military dimensions” of its nuclear programme – only to withdraw the concession at the end of the meeting.

The issue was Iran’s insistence on being given all the documents on which the IAEA bases the allegations of Iranian research related to nuclear weapons which Iran is expected to explain to the IAEA’s satisfaction.

The Feb. 20 negotiating text shows that the IAEA sought to evade any requirement for sharing any such documents by qualifying the commitment with the phrase “where appropriate”.

At the most recent meeting on Aug. 24, however, the IAEA negotiators, Deputy Director General for Safeguards Herman Nackaerts and Assistant Director General for Policy Rafael Grossi, agreed for the first time to a commitment to “deliver the documents related to activities claimed to have been conducted by Iran”, according to Soltanieh.

At the end of the meeting, however, Nackaerts and Grossi “put this language in brackets”, thus leaving it unresolved, Soltanieh said.

Former IAEA Director General Mohamed ElBaradei recalls in his 2011 memoirs that he had “constantly pressed the source of the information” on alleged Iranian nuclear weapons research – meaning the United States – “to allow us to share copies with Iran”. He writes that he asked how he could “accuse a person without revealing the accusations against him?”

ElBaradei also says Israel gave the IAEA a whole new set of documents in late summer 2009 “purportedly showing that Iran had continued with nuclear weapons studies until at least 2007″.

Soltanieh confirmed that the other unresolved issue is whether the IAEA investigation will be open-ended or not.

The Feb. 20 negotiating text showed that Iran demanded a discrete list of topics to which the IAEA inquiry would be limited and a requirement that each topic would be considered “concluded” once Iran had answered the questions and delivered the information requested.

But the IAEA insisted on being able to “return” to topics that had been “discussed earlier”, according to the February negotiating text.

That position remains unchanged, according to Soltanieh. The Iranian ambassador quoted an IAEA negotiator as asking, “What if next month we receive something else — some additional information?’”.

“If the IAEA had its way,” Soltanieh said, “It would be another 10 or 20 years.”

Soltanieh told IPS a meeting between Iran and the IAEA set for mid-October had been agreed before the IAEA Board of Governors earlier this month with Nackaerts and Grossi.

The Iranian ambassador said the IAEA officials had promised him that Director General Yukia Amano would announce the meeting during the Board meeting, but Amano made no such announcement.

Instead, after a meeting with Fereydoun Abbasi, Iran’s Vice President and head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, Amano only referred to the “readiness of Agency negotiators to meet with Iran in the near future.”

“He didn’t keep the promise,” said Soltanieh, adding that Iran would have to “study in the capital” how to respond.

Soltanieh elaborated on Abassi’s suggestion last week that the sabotage of power to the Fordow facility the night before an IAEA request for a snap inspection of the facility showed the agency could be infiltrated by “terrorists and saboteurs”.

“The objection we have is that the DG isn’t protecting confidential information,” said Soltanieh. “When they have information on how many centrifuges are working and how many are not working (in IAEA reports), this is a very serious concern.”

Iran has complained for years about information gathered by IAEA inspectors, including data on personnel in the Iranian nuclear programme, being made available to U.S., Israeli and European intelligence agencies.

*Gareth Porter, an investigative historian and journalist specialising in U.S. national security policy, received the UK-based Gellhorn Prize for journalism for 2011 for articles on the U.S. war in Afghanistan.

]]>In numerous op-eds and in testimonies before congressional audiences Mark Dubowitz, the executive director of the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies (FDD), has called for “crippling sanctions” against the Islamic Republic and its controversial nuclear program. Only days prior to the official commencement [...]]]>

In numerous op-eds and in testimonies before congressional audiences Mark Dubowitz, the executive director of the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies (FDD), has called for “crippling sanctions” against the Islamic Republic and its controversial nuclear program. Only days prior to the official commencement of the European Union embargo on Iranian oil, Mr. Dubowitz penned one such op-ed in Foreign Policy titled “Battle Rial” wherein he called upon the United States to step up “economic warfare” against the Islamic Republic and by extension its over 75 million inhabitants. Due to the many dubious assertions and conclusions presented in this article we feel a rebuttal is in order. But let us first examine the FDD and the type of democracy and freedom that it claims to defend and promote.

In numerous op-eds and in testimonies before congressional audiences Mark Dubowitz, the executive director of the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies (FDD), has called for “crippling sanctions” against the Islamic Republic and its controversial nuclear program. Only days prior to the official commencement of the European Union embargo on Iranian oil, Mr. Dubowitz penned one such op-ed in Foreign Policy titled “Battle Rial” wherein he called upon the United States to step up “economic warfare” against the Islamic Republic and by extension its over 75 million inhabitants. Due to the many dubious assertions and conclusions presented in this article we feel a rebuttal is in order. But let us first examine the FDD and the type of democracy and freedom that it claims to defend and promote.

History repeating?

The FDD’s leadership council includes three people who played a role in advocating policies that resulted directly or indirectly in much of the destruction and carnage that has swept across the Middle East in the last decade. Namely former CIA Director R. James Woolsey, neoconservative pundit William Kristol and Senator Joseph Lieberman, a longtime proponent of some of the most aggressive policies against Iran in Congress. Woolsey and Kristol persistently spread falsehoods regarding Saddam Hussein’s non-existent weapons of mass destruction in the run up to the American-led invasion. Ironically, the results of invading Iraq—aside from destroyed infrastructure and civilian deaths which by some estimates number in the hundreds of thousands—include the rise of a Shi’ite dominated regime now closely allied with the one in Tehran that the FDD is intent on destroying. The FDD’s advisory board also lists prominent neoconservative Richard Perle whose resume includes the advising of a firm that worked to “burnish Libya’s image and grow its economy” during Muammar Qaddafi’s brutal rule.

While the FDD is heavily focused on Iran, it is Mr. Dubowitz who has spearheaded its sanctions campaign against the country. In his article he contradicts statements by senior Obama administration officials including Defense Secretary Leon Panetta, the Director of National Intelligence James Clapper and CIA Director David Petraeus when he asserts that the Iranians are pursuing nuclear weapons. By implying that the clock is rapidly ticking until Iran obtains the bomb, he is also recycling what has become an infamous metaphor associated with the US’s legacy in the Middle East. His unsubstantiated claims even conflict with assessments from IDF chief Benny Gantz and the former heads of both Mossad and Shin Bet. Indeed, despite questions regarding the possibility of past weapons research, the international Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has found no evidence of the diversion of fissile material from Iranian nuclear sites for non-peaceful purposes. Apparently Mr. Dubowitz knows something others do not.

To lay the foundation for his arguments Mr. Dubowitz states that recent rounds of negotiations in Istanbul, Baghdad and Moscow did not result in tangible progress. But he does not bother to address a fundamental question: how can the United States and its allies expect Iran to seriously engage while they wage what is by Mr. Dubowtiz’s own admission “economic warfare?” This is not to absolve the Islamic Republic of its own contributions to the impasse, but balanced diplomacy must include give and take; it cannot be all stick and no carrot.

What have the US and its allies offered to Iran that can induce it to compromise? Besides fabricated fuel in exchange for the shipment of Iran’s approximately 150kg stockpile of 19.75% uranium, along with spare aviation parts and support in beefing up safety at the Bushehr power plant, not much else was offered. If President Obama’s dual-track policy is to prove effective, it needs to be recalibrated during the course of negotiations so that Iran has a reason to stay invested in the process.

Though perhaps better than the US-Russia deal offered to Iran in October 2009, the precipitous increase in economic sanctions—particularly those against Iran’s Central Bank and its energy sector—have made acceptance of a comparable deal or even a relatively more advantageous one incompatible with Iran’s domestic decision-making calculus. Too much pain has already been inflicted upon a long-suffering economy. The P5+1 (the five permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany) also continue to resist recognizing Iran’s right to enrich uranium for peaceful purposes. While by no means unconditional, uranium enrichment for peaceful purposes is a basic right guaranteed under the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

Rather than addressing the differences that impede the diplomatic process Mr. Dubowitz rings sensationalist alarm bells and pushes draconian economic measures which, while impacting Tehran’s cost-benefit analysis, can also devastate the lives of ordinary Iranians and result in a military conflict. Recall the effect of other extreme sanctions that were imposed on Iraq in the 1990s including the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Iraqi children, the depredation of the Iraqi economy and the dilapidation of all sources of resistance to the Baathist regime. Needless to say, those sanctions were only interrupted by the 2003 US-led invasion.

Questionable recommendations

Mr. Dubwoitz argues that “[f]or sanctions to work, Khamenei must be forced to make a fundamental decision between his nukes and his regime.” Apart from repeating the baseless assertion that Iran has nuclear weapons, Mr. Dubowitz’s main point is that the sanctions imposed thus far have not been sufficiently harsh. He accordingly calls upon the Obama administration to support legislation introduced by Reps. Ted Deutch (D-Fla.), Robert Dold (R-Ill.) and Sen. Mark Kirk (R-Ill.) that would blacklist the entire Iranian energy sector as a “zone of primary proliferation concern”. This legislation attempts to link Iran’s entire energy sector to its non-existent nuclear weapon program, an unprecedented move that seeks to deliver a knockout blow by further eroding revenues obtained through oil sales. Iran’s oil revenues account for 80% of its export earnings and allow it to purchase basic foodstuffs such as wheat and grain to feed the population, as well as prevent millions of households from being plunged into deprivation and hunger through government subsidies. In recent weeks the price of bread, the basic foodstuff of poorer Iranians, has increased by as much as a third, in large part as a result of the sanctions that Mr. Dubowitz so enthusiastically promotes.

The effort to blacklist any industry that facilitates the preponderance of the Iranian nuclear program, even if indirectly, can only be described as a concerted perversion of international law. Mr. Dubowtiz’s rationale can also be used to justify the embargo of foodstuffs or medicine that sustain Iran’s nuclear scientists and personnel so that they become incapable of furthering the technical development of Iran’s nuclear program. One might even make the case that this logic lies behind the assassination of a number of Iranian nuclear scientists, the culprits for whom are widely believed to be the Mojahedin-e Khalq (MEK) working in coordination with Israel. The MEK is a mortal enemy of the regime in Tehran, and currently on the State Department’s list of foreign terrorist organizations. The attacks it has coordinated against the regime and the Iranian lives it has endangered have not only resulted in their unpopularity among the vast majority of Iran’s population, they have also given the regime the perfect excuse to crack down on legitimate dissenters.

While sanctions at least initially directly targeted Iran’s nuclear program and later the Islamic Revolution Guards Corp (IRGC) and related organizations, they have turned out to be an all-encompassing iron fist hell-bent on destroying Iran’s most vital source of revenue which is not only important for Iran, but also the world economy. In this way Mr. Dubowitz’s key arguments also demonstrate the many dangers associated with so-called “smart sanctions”.

But Mr. Dubowitz even advocates targeting Iran’s automotive industry, which provides jobs to thousands of Iranians:

Economic warfare should not be limited to the energy sector. The United States and its allies should also target other areas of the Iranian economy, including the automotive sector, which is the largest part of Iran’s economy outside the energy industry.

The mind boggles at what connection he might contrive between Iran’s automotive sector and its nuclear program. What rationale can he offer other than pummeling Iran’s economy and thereby inflicting collective punishment on its people?

Goals and benefits

If Mr. Dubowitz’s aim is not a diplomatic solution but rather to drive an already angry and restive population to the point of despair so that it rises up and overthrows the ruling theocracy, he should state so. But is that achievable? The aftermath of Iran’s hotly contested and by many accounts fraudulent 2009 presidential election saw unprecedented protests and the rise of the Green Movement which was not a foreign induced uprising but one that had been in the making for some 20 years. It has not succeeded because the opposition is inadequately organized, does not have a comprehensive program or plan for realizing its goals and its leadership and advisers have been rounded up, jailed and silenced. The disorganized and divided opposition, both inside and outside the country, is now in an even weaker state than before. But the Green Movement has still rejected foreign intervention and sanctions as a form of collective punishment, and their enfeebled position certainly isn’t helped by the constant threat of foreign invasion. If Iran’s economy declines further and major budgetary shortfalls arise and inflationary pressures persist, bread riots of the kind witnessed during the Rafsanjani era can indeed result. But aside from the ethics associated with inducing a population to revolt by bringing them to the brink of starvation, such riots, without a political program or set of objectives, that uprising will also be quickly repressed and controlled by the security forces. What then can be gained from this approach other than inflicting pain upon an innocent population?

While there is little doubt that hardliners around Ayatollah Ali Ali Khamenei’s office along with authoritarian elements of the radical clergy have and will continue to repress opposition to their grip on power, the constant threat of war and a state of emergency can only benefit the security forces and legitimize their raison d’être in the face of an external enemy. Meanwhile oil revenues which mainly flow into the country from China, Japan and India will remain firmly in the hands of the authorities and the repressive organs of the state. Youth unemployment, which accounts for 70% of the unemployment in Iran, will increase and the state of the underprivileged and retirees reliant on state handouts will decline further under the brunt of such policies. One should also point to the clear failure of comparable sanctions regimes in the case of Cuba and also Iraq, which ultimately resulted in a military invasion to impose regime change at great human cost. While states under such sanctions regimes might be weakened in relative terms to other states in the international system, vis-à-vis their respective populations and civil societies they actually become more powerful.

What exactly is Mr. Dubowitz’s desired endgame for US policy on Iran and the “democracy” that the FDD supposedly supports for the Iranian people? The answer is in a piece published by the Los Angeles Times where Mr. Dubowitz is paraphrased as saying, “[the sanctions] could take until the end of 2013 to bring Iran’s economy to wholesale collapse.” In other words, spurring chaos in a geopolitically important middle eastern country by destroying its economic infrastructure is fair game.

Under such conditions Iran’s dwindling middle class, already under great pressure, finds itself between a rock and a hard place: a theocracy that denies its basic political and civil liberties at home and economic desolation exacerbated by unparalleled and crippling sanctions. Though the Iranian government’s own incompetence and endemic corruption in managing the economy has had a major hand in accelerating chronic inflation, it is undeniable that a decline in oil revenues will further harm what’s arguably the most pro-American population in the Middle East.

Will Mr. Dubowitz’s recommendations result in more US-friendly concessions from the Iranian government? Khamenei has heavily invested in the development of Iran’s nuclear program. Many other regime officialdom including former President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani have also praised Iran’s technical achievements over the years and emphasized the importance of the program to Iran’s role as a regional player. Due to the regime’s shortcomings elsewhere and growing legitimacy deficit, the program’s “technological prowess” and importance to Iran’s future energy needs have also been overstated and oversold to the general public, many of whom are no doubt skeptical of the expediency of current state nuclear policy. That being said, because of the extent of political capital invested in the programme it is highly unlikely that Khamenei will make major concessions without a deal that offers a face-saving formula.

But instead of reconsidering the paradigm of engagement with Iran, Mr. Dubowitz pushes for even more “crippling sanctions” and ultimately a military attack by writing that Obama “needs to unite the country in moving beyond sanctions and preparing for U.S. military strikes against Iran’s nuclear weapons program.”