by Robert E. Hunter

…we have reached the conclusion that there is not enough recent progress in our bilateral agenda with Russia to hold a U.S.-Russia Summit in early September…Russia’s disappointing decision to grant Edward Snowden temporary asylum was also a factor…

— White House Office of the Press Secretary, August 7, 2013

[...]]]>by Robert E. Hunter

…we have reached the conclusion that there is not enough recent progress in our bilateral agenda with Russia to hold a U.S.-Russia Summit in early September…Russia’s disappointing decision to grant Edward Snowden temporary asylum was also a factor…

— White House Office of the Press Secretary, August 7, 2013

…Having in mind the great importance of this conference and the hopes that the peoples of all the world have reposed in this meeting…I see no reason to use this [U-2] incident to disrupt the conference…

— President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Paris, May 16, 1960

The cancelling of a projected summit meeting next month with Russian President Vladimir Putin by President Barack Obama has probably attracted more attention than anything substantive likely to have occurred in that meeting. Or at least anything that could not have been achieved through ordinary diplomatic means. In other words, the significance of this meeting was overrated from the beginning, like most other summits in modern history.

Summits involving the Russians have featured in world politics since Napoleon met Czar Alexander I in 1807 on a raft in the middle of the Neman River in the town of Tilsit. Notable were the three World War II summits wherein Marshall Stalin met with the US president in Tehran, Yalta and Potsdam — with the British prime minister tagging along — that dealt with wartime strategy and the future of Europe. Not so much was at stake this time around.

Admittedly, Obama is not cancelling his attendance at the G-8 summit in St. Petersburg, also in Putin’s Russia. But even the G-8 summits are not worth much in terms of substance, compared with what could be achieved, again, through so-called ordinary diplomatic means.

This is not the place to review the full history of modern summitry. In the main, they are held because publics (and politics) expect them and demand “results.” The invention of the airplane and global television, not the seriousness of the agenda, is the causative agent. Almost always, summit agreements, enshrined in official communiqués, are worked out in advance by lower-level officials, with perhaps an item or two — a “sticking point” or “window dressing” — to be dealt with at the top. To be sure, a forthcoming summit, like “the prospect of hanging” in Samuel Johnson’s phrase, “concentrates the mind wonderfully” or, in this case, provides a spur to bureaucratic and diplomatic activity. Issues that have been sitting on the shelf or in the too-hard inbox may get dusted off and resolved because top leaders are getting together with media attention, pageantry, ruffles and flourishes, state dinners and expectations. This is not something to be left to chance nor to risk a potential blunder by the US president or his opposite number, whether friend or foe.

This is not cynicism, it is reality. Yours truly speaks from experience, having been involved with more than 20 meetings of US presidents with other heads of state and government. I witnessed only two where what the president and his interlocutor worked out at the table made a significant difference: President Jimmy Carter’s 1980 White House meetings with Israeli Prime Minister Meacham Begin and (two weeks later) with Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat. Serious decisions were taken because the US president was the American action officer for Arab-Israeli peacemaking; he “rolled his own.”

Summits can also cause damage, as did the 2008 Bucharest NATO summit, where European heads of state and government balked at the US president’s desire to move Ukraine and Georgia a tiny step toward NATO membership. Instead, they made the meaningless pledge that, in time, it would happen. Both the Georgian and Russian presidents read this as a strategic commitment. The upshot was the short Russia-Georgia war that set back Western and Russian efforts to deal with more important matters on their agenda.

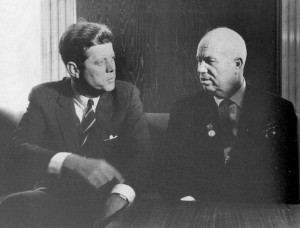

Most notorious was the summit President John Kennedy hastily sought in 1961 with Nikita Khrushchev. Their Vienna meeting was represented as having set back the untested president’s efforts to establish himself with the bullying Soviet leader. Some historians believe this encounter encouraged Khrushchev to take actions that produced the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Even worse than the expectations of success that summits generate is the notion that good chemistry between leaders can have a decisive influence. Nonsense. Of course it is better for there to be positive relations, the ability to “do business” as Margaret Thatcher once said about Mikhael Gorbachev — provided, of course, there is “business” to be “done.” Indeed, assessments of chemistry or the lack thereof just get in the way when they obscure realities of power, the interests of nations and leaders’ domestic politics, which are the real stuff of relations between and among states. Many of history’s worst villains have been charming in person.

Cancelling the Obama-Putin summit has taken place over developments that in the course of history are relatively trivial, confirming that it was unlikely to have been significant. If something of importance was to be settled, ways would have been found to finesse the distractions.

Russian misbehavior included not handing over Edward Snowden, the master leaker of sensitive US information, and the Duma’s passing a law against gays and lesbians. US misbehavior included Congress’ condemnation of the Russian trial of a dead man, Sergei Magnitsky, who had been a thorn in Putin’s side. Notably, the reasons for cancelling this summit lean heavily on domestic politics, not matters of state.

What happened with Eisenhower in 1960, referred to above, was much more consequential. The leaders of the four major powers (the US, Soviet Union, Britain and France) were to meet in Paris, for the first time in years, to reduce misunderstandings between East and West that were making inherent dangers even worse.

Ironically, the triggering event then was also about intelligence; this time it is Snowden, that time it was Francis Gary Powers, the hapless pilot of a US U-2 Reconnaissance aircraft shot down over the Soviet Union less than two weeks before the summit. What then transpired — Obama cancelling in 2013 and Khrushchev displaying his patented histrionics in 1960 — fed into the domestic politics of each side. Just as Obama and Putin must both be wishing that Snowden had gone to Venezuela instead of Hong Kong and then Moscow, Khrushchev may well have cursed the Soviet Air Defense Forces for their untimely shooting down of an American spy plane that both sides knew reduced fears of an accidental nuclear war. Ike probably also cursed himself for letting the CIA launch a U-2 flight so soon before the Paris summit.

The comparison of 1960 and 2013 can be taken a step further. Then, at a particularly dangerous moment for the world, the Soviet Union was one of the two most powerful countries. Now Russia is a second-rate power whose greatest importance to the US lies in what it could well become in the future and its current impact, by facts of size and propinquity, on places and problems the US at the moment cares more about.

But a new Cold War? Again, nonsense. Rather, as political analyst William Lanouette has jibed, a “Cold-Shoulder War.”

To begin with, “Cold War” needs to be defined with precision. It refers to the period when the US and Soviet Union were psychologically unable to distinguish between issues on which they could negotiate in their mutual self-interest and those on which neither could compromise. They were so locked into their perceptions and rhetoric that they could not even fathom possible common interests. That is clearly not true, now, and will not be.

The US-Soviet Cold War began to end in the 1960s, when the two countries developed the weapons and doctrine of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD), which in practice meant that each side accepted responsibility for the others’ ultimate security against nuclear annihilation. This spawned détente, the eventual end of the Cold War, and the sinking of the Soviet Union and European communism through their internal contractions.

Do US-Russian relations matter? Certainly, but not like US-Soviet relations before 1989. The difference is visible in today’s elevation of US concerns over internal developments in Russia, although, for Russia to be fully accepted, respected and trusted on the world stage, it must conform to growing civilizing tendencies in international relations and state behavior within at least a fair amount of the globe. Far more importantly, there are US-Russian differences, both in view and national interests, which make relations difficult at times but must be sorted out in one way or another.

A key focal point of today’s differences exists in the Middle East. The US objects to Russia’s unwillingness to assist efforts to depose the regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria, which the US president called for before thinking through the means or implications. It is also not confident that Russia truly supports the US-led confrontation over Iran’s nuclear program.

But both US positions beg big questions: on Syria, what the consequences would be there and in the broader region if the US got its way with Moscow, given the unlikelihood of a good outcome in Syria, the slow-rolling Sunni-Shiite civil war underway in the heart of the Middle East, Washington’s lack of clarity over what it is prepared to do militarily and even what outcome would best serve US interests. Russia might thus be cut some slack over its temporizing.

Regarding Iran, the US wants Russia, China and Western powers to hold firm on sanctions (while Congress wants to ratchet them up, despite the inauguration of a new Iranian president who could be better for the US than his predecessor). But Washington has yet to demonstrate that it will negotiate seriously with Iran, and, as states do when there is a vacuum, Moscow is taking advantage.

In addition to dismantling some remaining Cold War relics, notably the excessive level of nuclear weapons both countries still deploy (some absurdly kept on alert), is the issue of when and how much Russia will regain a prominent role in international politics, how and how much the US will try to oppose that inevitable “rebalancing” while its own capacity to affect global events has diminished significantly and if Washington and Moscow can work out sensible rules of the road with one another in the Middle East, Southwest Asia and elsewhere. Russia needs us as partner in some areas; in others it will inevitably be our rival and vice versa.

As two great hydrocarbon producers with interests and engagements that touch or overlap — such as concerns about terrorism, desires that the Afghan curse not cause both of them further troubles in Southwest Asia and the need to influence the rise of new kids on the block (China and India) — the US and Russia have lots to talk about.

But Obama and Putin wining and dining one another has little to do with it.

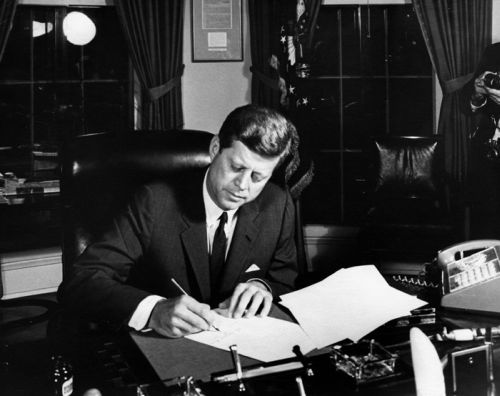

]]>It was exactly 50 years ago when then-President John F. Kennedy took to the airwaves to inform the world that the Soviet Union was introducing nuclear-armed missiles into Cuba and that he had ordered a blockade of the island – and would consider stronger action – to force their removal.

[...]]]> It was exactly 50 years ago when then-President John F. Kennedy took to the airwaves to inform the world that the Soviet Union was introducing nuclear-armed missiles into Cuba and that he had ordered a blockade of the island – and would consider stronger action – to force their removal.

It was exactly 50 years ago when then-President John F. Kennedy took to the airwaves to inform the world that the Soviet Union was introducing nuclear-armed missiles into Cuba and that he had ordered a blockade of the island – and would consider stronger action – to force their removal.

“It was the most chilling speech in the history of the U.S. presidency,” according to Peter Kornbluh of the National Security Archive, who has spent several decades working to declassify key documents and other material that would shed light on the 13-day crisis that most historians believe brought the world closer to nuclear war than at any other moment.

Indeed, Kennedy’s military advisers were urging a pre-emptive strike against the missile installations on the island, unaware that some of them were already armed.

Several days later, the crisis was resolved when Soviet President Nikita Krushchev appeared to capitulate by agreeing to withdraw the missiles in exchange for a U.S. pledge not to invade Cuba.

“We’ve been eyeball to eyeball, and the other fellow just blinked,” exulted Secretary of State Dean Rusk in what became the accepted interpretation of the crisis’ resolution.

“Kennedy’s victory in the messy and inconclusive Cold War naturally came to dominate the politics of U.S. foreign policy,” write Leslie Gelb, president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations in a recent foreignpolicy.com article entitled “The Myth That Screwed Up 50 Years of U.S. Foreign Policy.”

“It deified military power and willpower and denigrated the give-and-take of diplomacy,” he wrote. “It set a standard for toughness and risky dueling with bad guys that could not be matched – because it never happened in the first place.”

What the U.S. public didn’t know was that Krushchev’s concession was matched by another on Washington’s part as a result of secret diplomacy, conducted mainly by Kennedy’s brother, Robert, and Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin.

Indeed, in exchange for removing the missiles from Cuba, Moscow obtained an additional concession by Washington: to remove its own force of nuclear-tipped Jupiter missiles from Turkey within six months – a concession that Washington insisted should remain secret.

“The myth (of the Cuban missile crisis), not the reality, became the measure for how to bargain with adversaries,” according to Gelb, who interviewed many of the principals.

Writing in a New York Times op-ed last week, Michael Dobbs, a former Washington Post reporter and Cold War historian, noted that the “eyeball to eyeball” image “has contributed to some of our most disastrous foreign policy decisions, from the escalation of the Vietnam War under (Lyndon) Johnson to the invasion of Iraq under George W. Bush.”

Dobbs also says Bush made a “fateful error, in a 2002 speech in Cincinnati when he depicted Kennedy as the father of his pre-emptive war doctrine. In fact, Kennedy went out of his way to avoid such a war.”

To Graham Allison, director of the Belfer Center at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, whose research into those fateful “13 days in October” has brought much of the back-and-forth to light, “the lessons of the crisis for current policy have never been greater.”

In a Foreign Affairs article published last summer, he described the current confrontation between the U.S. and Iran as “a Cuban missile crisis in slow motion”.

Kennedy, he wrote, was given two options by his advisers: “attack or accept Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba.” But the president rejected both and instead was determined to forge a mutually acceptable compromise backed up by a threat to attack Cuba within 24 hours unless Krushchev accepted the deal.

Today, President Barack Obama is being faced with a similar binary choice, according to Allison: to acquiesce in Iran’s acquisition of a nuclear bomb or carry out a preventive air strike that, at best, could delay Iran’s nuclear programme by some years.

A “Kennedyesque third option,” he wrote, would be an agreement that verifiably constrains Iran’s nuclear programme in exchange for a pledge not to attack Iran so long as it complied with those constraints.

“I would hope that immediately after the election, the U.S. government will also turn intensely to the search for something that’s not very good – because it won’t be very good – but that is significantly better than attacking on the one hand or acquiescing on the other,” Allison told the Voice of America last week.

This very much appears to be what the Obama administration prefers, particularly in light of as-yet unconfirmed reports over the weekend that both Washington and Tehran have agreed in principle to direct bilateral talks, possibly within the framework of the P5+1 negotiations that also involve Britain, France, China, Russia and Germany, after the Nov. 6 election.

Allison also noted a parallel between the Cuban crisis and today’s stand-off between the U.S. and Iran – the existence of possible third-party spoilers.

Fifty years ago, Cuban Prime Minister Fidel Castro had favoured facing down the U.S. threat and even launching the missiles in the event of a U.S. attack.

But because the Cubans lacked direct control over the missiles, which were under Soviet command, they could be ignored. Moreover, Kennedy warned the Kremlin that it “would be held accountable for any attack against the United States emanating from Cuba, however it started,” according to Allison.

The fact that Israel, which has repeatedly threatened to attack Iran’s nuclear sites unilaterally, actually has the assets to act on those threats makes the situation today more complicated than that faced by Kennedy.

“Due to the secrecy surrounding the resolution of the Cuban missile crisis, the lesson that became ingrained in U.S. foreign policy-making was the importance of a show of force to make your opponent back down,” Kornbluh told IPS.

“But the real lesson is one of commitment to diplomacy, negotiation and compromise, and that was made possible by Kennedy’s determination to avoid a pre-emptive strike, which he knew would open a Pandora’s box in a nuclear age.”

]]>In his debunking of the myths surrounding the Cuban missile crisis, Slate journalist Fred Kaplan derives lessons that can be applied to the ongoing dispute over Iran’s nuclear program. His second and third points, in particular, stand out (emphasis mine):

Second, at some point, one side might clearly have the [...]]]>

In his debunking of the myths surrounding the Cuban missile crisis, Slate journalist Fred Kaplan derives lessons that can be applied to the ongoing dispute over Iran’s nuclear program. His second and third points, in particular, stand out (emphasis mine):

In his debunking of the myths surrounding the Cuban missile crisis, Slate journalist Fred Kaplan derives lessons that can be applied to the ongoing dispute over Iran’s nuclear program. His second and third points, in particular, stand out (emphasis mine):

Second, at some point, one side might clearly have the upper hand, in which case it should seek ways to give the other side a way out. This doesn’t necessarily mean surrendering the interests at stake. The Jupiter missiles that JFK traded weren’t much good anyway. The United States was about to station new Polaris submarines in the Mediterranean; each sub carried 16 nuclear missiles and was less vulnerable to attack. The United States, in other words, gave up nothing in military capability.

Third, there is no contradiction between striking a deal and maintaining vigilance; compromise is not the same as appeasement. According to a cleverly titled new book by David Coleman, The Fourteenth Day: JFK and the Aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis, disputes continued for months after the Turkish deal was struck, and tensions occasionally flared, over the terms and timing of the withdrawal of Soviet weapons from Cuba. Kennedy held his ground. But neither side stormed off or retriggered the crisis.

By Noam Chomsky

Published by Tom Dispatch

Significant anniversaries are solemnly commemorated — Japan’s attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, for example. Others are ignored, and we can often learn valuable lessons from them about what is likely to lie ahead. Right [...]]]>

By Noam Chomsky

Published by Tom Dispatch

Significant anniversaries are solemnly commemorated — Japan’s attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, for example. Others are ignored, and we can often learn valuable lessons from them about what is likely to lie ahead. Right now, in fact.

At the moment, we are failing to commemorate the 50th anniversary of President John F. Kennedy’s decision to launch the most destructive and murderous act of aggression of the post-World War II period: the invasion of South Vietnam, later all of Indochina, leaving millions dead and four countries devastated, with casualties still mounting from the long-term effects of drenching South Vietnam with some of the most lethal carcinogens known, undertaken to destroy ground cover and food crops.

The prime target was South Vietnam. The aggression later spread to the North, then to the remote peasant society of northern Laos, and finally to rural Cambodia, which was bombed at the stunning level of all allied air operations in the Pacific region during World War II, including the two atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In this, Henry Kissinger’s orders were being carried out — “anything that flies on anything that moves” — a call for genocide that is rare in the historical record. Little of this is remembered. Most was scarcely known beyond narrow circles of activists.

When the invasion was launched 50 years ago, concern was so slight that there were few efforts at justification, hardly more than the president’s impassioned plea that “we are opposed around the world by a monolithic and ruthless conspiracy that relies primarily on covert means for expanding its sphere of influence” and if the conspiracy achieves its ends in Laos and Vietnam, “the gates will be opened wide.”

When the invasion was launched 50 years ago, concern was so slight that there were few efforts at justification, hardly more than the president’s impassioned plea that “we are opposed around the world by a monolithic and ruthless conspiracy that relies primarily on covert means for expanding its sphere of influence” and if the conspiracy achieves its ends in Laos and Vietnam, “the gates will be opened wide.”

Elsewhere, he warned further that “the complacent, the self-indulgent, the soft societies are about to be swept away with the debris of history [and] only the strong… can possibly survive,” in this case reflecting on the failure of U.S. aggression and terror to crush Cuban independence.

By the time protest began to mount half a dozen years later, the respected Vietnam specialist and military historian Bernard Fall, no dove, forecast that “Vietnam as a cultural and historic entity… is threatened with extinction…[as]…the countryside literally dies under the blows of the largest military machine ever unleashed on an area of this size.” He was again referring to South Vietnam.

When the war ended eight horrendous years later, mainstream opinion was divided between those who described the war as a “noble cause” that could have been won with more dedication, and at the opposite extreme, the critics, to whom it was “a mistake” that proved too costly. By 1977, President Carter aroused little notice when he explained that we owe Vietnam “no debt” because “the destruction was mutual.”

There are important lessons in all this for today, even apart from another reminder that only the weak and defeated are called to account for their crimes. One lesson is that to understand what is happening we should attend not only to critical events of the real world, often dismissed from history, but also to what leaders and elite opinion believe, however tinged with fantasy. Another lesson is that alongside the flights of fancy concocted to terrify and mobilize the public (and perhaps believed by some who are trapped in their own rhetoric), there is also geostrategic planning based on principles that are rational and stable over long periods because they are rooted in stable institutions and their concerns. That is true in the case of Vietnam as well. I will return to that, only stressing here that the persistent factors in state action are generally well concealed.

The Iraq war is an instructive case. It was marketed to a terrified public on the usual grounds of self-defense against an awesome threat to survival: the “single question,” George W. Bush and Tony Blair declared, was whether Saddam Hussein would end his programs of developing weapons of mass destruction. When the single question received the wrong answer, government rhetoric shifted effortlessly to our “yearning for democracy,” and educated opinion duly followed course; all routine.

Later, as the scale of the U.S. defeat in Iraq was becoming difficult to suppress, the government quietly conceded what had been clear all along. In 2007-2008, the administration officially announced that a final settlement must grant the U.S. military bases and the right of combat operations, and must privilege U.S. investors in the rich energy system — demands later reluctantly abandoned in the face of Iraqi resistance. And all well kept from the general population.

Gauging American Decline

With such lessons in mind, it is useful to look at what is highlighted in the major journals of policy and opinion today. Let us keep to the most prestigious of the establishment journals, Foreign Affairs. The headline blaring on the cover of the December 2011 issue reads in bold face: “Is America Over?”

The title article calls for “retrenchment” in the “humanitarian missions” abroad that are consuming the country’s wealth, so as to arrest the American decline that is a major theme of international affairs discourse, usually accompanied by the corollary that power is shifting to the East, to China and (maybe) India.

The lead articles are on Israel-Palestine. The first, by two high Israeli officials, is entitled “The Problem is Palestinian Rejection”: the conflict cannot be resolved because Palestinians refuse to recognize Israel as a Jewish state — thereby conforming to standard diplomatic practice: states are recognized, but not privileged sectors within them. The demand is hardly more than a new device to deter the threat of political settlement that would undermine Israel’s expansionist goals.

The opposing position, defended by an American professor, is entitled “The Problem Is the Occupation.” The subtitle reads “How the Occupation is Destroying the Nation.” Which nation? Israel, of course. The paired articles appear under the heading “Israel under Siege.”

The January 2012 issue features yet another call to bomb Iran now, before it is too late. Warning of “the dangers of deterrence,” the author suggests that “skeptics of military action fail to appreciate the true danger that a nuclear-armed Iran would pose to U.S. interests in the Middle East and beyond. And their grim forecasts assume that the cure would be worse than the disease — that is, that the consequences of a U.S. assault on Iran would be as bad as or worse than those of Iran achieving its nuclear ambitions. But that is a faulty assumption. The truth is that a military strike intended to destroy Iran’s nuclear program, if managed carefully, could spare the region and the world a very real threat and dramatically improve the long-term national security of the United States.”

Others argue that the costs would be too high, and at the extremes some even point out that an attack would violate international law — as does the stand of the moderates, who regularly deliver threats of violence, in violation of the U.N. Charter.

Let us review these dominant concerns in turn.

American decline is real, though the apocalyptic vision reflects the familiar ruling class perception that anything short of total control amounts to total disaster. Despite the piteous laments, the U.S. remains the world dominant power by a large margin, and no competitor is in sight, not only in the military dimension, in which of course the U.S. reigns supreme.

China and India have recorded rapid (though highly inegalitarian) growth, but remain very poor countries, with enormous internal problems not faced by the West. China is the world’s major manufacturing center, but largely as an assembly plant for the advanced industrial powers on its periphery and for western multinationals. That is likely to change over time. Manufacturing regularly provides the basis for innovation, often breakthroughs, as is now sometimes happening in China. One example that has impressed western specialists is China’s takeover of the growing global solar panel market, not on the basis of cheap labor but by coordinated planning and, increasingly, innovation.

But the problems China faces are serious. Some are demographic, reviewed inScience, the leading U.S. science weekly. The study shows that mortality sharply decreased in China during the Maoist years, “mainly a result of economic development and improvements in education and health services, especially the public hygiene movement that resulted in a sharp drop in mortality from infectious diseases.” This progress ended with the initiation of the capitalist reforms 30 years ago, and the death rate has since increased.

Furthermore, China’s recent economic growth has relied substantially on a “demographic bonus,” a very large working-age population. “But the window for harvesting this bonus may close soon,” with a “profound impact on development”: “Excess cheap labor supply, which is one of the major factors driving China’s economic miracle, will no longer be available.”

Demography is only one of many serious problems ahead. For India, the problems are far more severe.

Not all prominent voices foresee American decline. Among international media, there is none more serious and responsible than the London Financial Times. It recently devoted a full page to the optimistic expectation that new technology for extracting North American fossil fuels might allow the U.S. to become energy independent, hence to retain its global hegemony for a century. There is no mention of the kind of world the U.S. would rule in this happy event, but not for lack of evidence.

At about the same time, the International Energy Agency reported that, with rapidly increasing carbon emissions from fossil fuel use, the limit of safety will be reached by 2017 if the world continues on its present course. “The door is closing,” the IEA chief economist said, and very soon it “will be closed forever.”

Shortly before the U.S. Department of Energy reported the most recent carbon dioxide emissions figures, which “jumped by the biggest amount on record” to a level higher than the worst-case scenario anticipated by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). That came as no surprise to many scientists, including the MIT program on climate change, which for years has warned that the IPCC predictions are too conservative.

Such critics of the IPCC predictions receive virtually no public attention, unlike the fringe of denialists who are supported by the corporate sector, along with huge propaganda campaigns that have driven Americans off the international spectrum in dismissal of the threats. Business support also translates directly to political power. Denialism is part of the catechism that must be intoned by Republican candidates in the farcical election campaign now in progress, and in Congress they are powerful enough to abort even efforts to inquire into the effects of global warming, let alone do anything serious about it.

In brief, American decline can perhaps be stemmed if we abandon hope for decent survival, prospects that are all too real given the balance of forces in the world.

“Losing” China and Vietnam

Putting such unpleasant thoughts aside, a close look at American decline shows that China indeed plays a large role, as it has for 60 years. The decline that now elicits such concern is not a recent phenomenon. It traces back to the end of World War II, when the U.S. had half the world’s wealth and incomparable security and global reach. Planners were naturally well aware of the enormous disparity of power, and intended to keep it that way.

The basic viewpoint was outlined with admirable frankness in a major state paper of 1948 (PPS 23). The author was one of the architects of the New World Order of the day, the chair of the State Department Policy Planning Staff, the respected statesman and scholar George Kennan, a moderate dove within the planning spectrum. He observed that the central policy goal was to maintain the “position of disparity” that separated our enormous wealth from the poverty of others. To achieve that goal, he advised, “We should cease to talk about vague and… unreal objectives such as human rights, the raising of the living standards, and democratization,” and must “deal in straight power concepts,” not “hampered by idealistic slogans” about “altruism and world-benefaction.”

Kennan was referring specifically to Asia, but the observations generalize, with exceptions, for participants in the U.S.-run global system. It was well understood that the “idealistic slogans” were to be displayed prominently when addressing others, including the intellectual classes, who were expected to promulgate them.

The plans that Kennan helped formulate and implement took for granted that the U.S. would control the Western Hemisphere, the Far East, the former British empire (including the incomparable energy resources of the Middle East), and as much of Eurasia as possible, crucially its commercial and industrial centers. These were not unrealistic objectives, given the distribution of power. But decline set in at once.

In 1949, China declared independence, an event known in Western discourse as “the loss of China” — in the U.S., with bitter recriminations and conflict over who was responsible for that loss. The terminology is revealing. It is only possible to lose something that one owns. The tacit assumption was that the U.S. owned China, by right, along with most of the rest of the world, much as postwar planners assumed.

The “loss of China” was the first major step in “America’s decline.” It had major policy consequences. One was the immediate decision to support France’s effort to reconquer its former colony of Indochina, so that it, too, would not be “lost.”

Indochina itself was not a major concern, despite claims about its rich resources by President Eisenhower and others. Rather, the concern was the “domino theory,” which is often ridiculed when dominoes don’t fall, but remains a leading principle of policy because it is quite rational. To adopt Henry Kissinger’s version, a region that falls out of control can become a “virus” that will “spread contagion,” inducing others to follow the same path.

In the case of Vietnam, the concern was that the virus of independent development might infect Indonesia, which really does have rich resources. And that might lead Japan — the “superdomino” as it was called by the prominent Asia historian John Dower — to “accommodate” to an independent Asia as its technological and industrial center in a system that would escape the reach of U.S. power. That would mean, in effect, that the U.S. had lost the Pacific phase of World War II, fought to prevent Japan’s attempt to establish such a New Order in Asia.

The way to deal with such a problem is clear: destroy the virus and “inoculate” those who might be infected. In the Vietnam case, the rational choice was to destroy any hope of successful independent development and to impose brutal dictatorships in the surrounding regions. Those tasks were successfully carried out — though history has its own cunning, and something similar to what was feared has since been developing in East Asia, much to Washington’s dismay.

The most important victory of the Indochina wars was in 1965, when a U.S.-backed military coup in Indonesia led by General Suharto carried out massive crimes that were compared by the CIA to those of Hitler, Stalin, and Mao. The “staggering mass slaughter,” as the New York Times described it, was reported accurately across the mainstream, and with unrestrained euphoria.

It was “a gleam of light in Asia,” as the noted liberal commentator James Reston wrote in the Times. The coup ended the threat of democracy by demolishing the mass-based political party of the poor, established a dictatorship that went on to compile one of the worst human rights records in the world, and threw the riches of the country open to western investors. Small wonder that, after many other horrors, including the near-genocidal invasion of East Timor, Suharto was welcomed by the Clinton administration in 1995 as “our kind of guy.”

Years after the great events of 1965, Kennedy-Johnson National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy reflected that it would have been wise to end the Vietnam war at that time, with the “virus” virtually destroyed and the primary domino solidly in place, buttressed by other U.S.-backed dictatorships throughout the region.

Similar procedures have been routinely followed elsewhere. Kissinger was referring specifically to the threat of socialist democracy in Chile. That threat was ended on another forgotten date, what Latin Americans call “the first 9/11,” which in violence and bitter effects far exceeded the 9/11 commemorated in the West. A vicious dictatorship was imposed in Chile, one part of a plague of brutal repression that spread through Latin America, reaching Central America under Reagan. Viruses have aroused deep concern elsewhere as well, including the Middle East, where the threat of secular nationalism has often concerned British and U.S. planners, inducing them to support radical Islamic fundamentalism to counter it.

The Concentration of Wealth and American Decline

Despite such victories, American decline continued. By 1970, U.S. share of world wealth had dropped to about 25%, roughly where it remains, still colossal but far below the end of World War II. By then, the industrial world was “tripolar”: US-based North America, German-based Europe, and East Asia, already the most dynamic industrial region, at the time Japan-based, but by now including the former Japanese colonies Taiwan and South Korea, and more recently China.

At about that time, American decline entered a new phase: conscious self-inflicted decline. From the 1970s, there has been a significant change in the U.S. economy, as planners, private and state, shifted it toward financialization and the offshoring of production, driven in part by the declining rate of profit in domestic manufacturing. These decisions initiated a vicious cycle in which wealth became highly concentrated (dramatically so in the top 0.1% of the population), yielding concentration of political power, hence legislation to carry the cycle further: taxation and other fiscal policies, deregulation, changes in the rules of corporate governance allowing huge gains for executives, and so on.

Meanwhile, for the majority, real wages largely stagnated, and people were able to get by only by sharply increased workloads (far beyond Europe), unsustainable debt, and repeated bubbles since the Reagan years, creating paper wealth that inevitably disappeared when they burst (and the perpetrators were bailed out by the taxpayer). In parallel, the political system has been increasingly shredded as both parties are driven deeper into corporate pockets with the escalating cost of elections, the Republicans to the level of farce, the Democrats (now largely the former “moderate Republicans”) not far behind.

A recent study by the Economic Policy Institute, which has been the major source of reputable data on these developments for years, is entitled Failure by Design. The phrase “by design” is accurate. Other choices were certainly possible. And as the study points out, the “failure” is class-based. There is no failure for the designers. Far from it. Rather, the policies are a failure for the large majority, the 99% in the imagery of the Occupy movements — and for the country, which has declined and will continue to do so under these policies.

One factor is the offshoring of manufacturing. As the solar panel example mentioned earlier illustrates, manufacturing capacity provides the basis and stimulus for innovation leading to higher stages of sophistication in production, design, and invention. That, too, is being outsourced, not a problem for the “money mandarins” who increasingly design policy, but a serious problem for working people and the middle classes, and a real disaster for the most oppressed, African Americans, who have never escaped the legacy of slavery and its ugly aftermath, and whose meager wealth virtually disappeared after the collapse of the housing bubble in 2008, setting off the most recent financial crisis, the worst so far.

Noam Chomsky is Institute Professor emeritus in the MIT Department of Linguistics and Philosophy. He is the author of numerous best-selling political works. His latest books are Making the Future: Occupations, Intervention, Empire, and Resistance, The Essential Chomsky (edited by Anthony Arnove), a collection of his writings on politics and on language from the 1950s to the present, Gaza in Crisis, with Ilan Pappé, and Hopes and Prospects, also available as an audiobook. To listen to Timothy MacBain’s latest Tomcast audio interview in which Chomsky offers an anatomy of American defeats in the Greater Middle East, click here, or download it to your iPod here.

[Note: Part 2 of Noam Chomsky’s discussion of American decline, “The Imperial Way,” will be posted at TomDispatch tomorrow.]

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter @TomDispatch and join us on Facebook.

Copyright 2012 Noam Chomsky

]]>