Second article in a series on minimum wages.

Note: This is an expanded, footnoted version of the article published by Inter Press Service.

In 1958, when New York State was considering raising its minimum wage 33% from $0.75 to $1.00, merchants at hearings complained that their profit margins were so small that [...]]]>

Seattle

Second article in a series on minimum wages.

Note: This is an expanded, footnoted version of the article published by Inter Press Service.

In 1958, when New York State was considering raising its minimum wage 33% from $0.75 to $1.00, merchants at hearings complained that their profit margins were so small that the increase would force them to cut their work forces or go out of business.[1] In Seattle in 2014 at hearings on a proposed 61% minimum wage increase from $9.32 to $15.00, some businesses voiced the same fears.

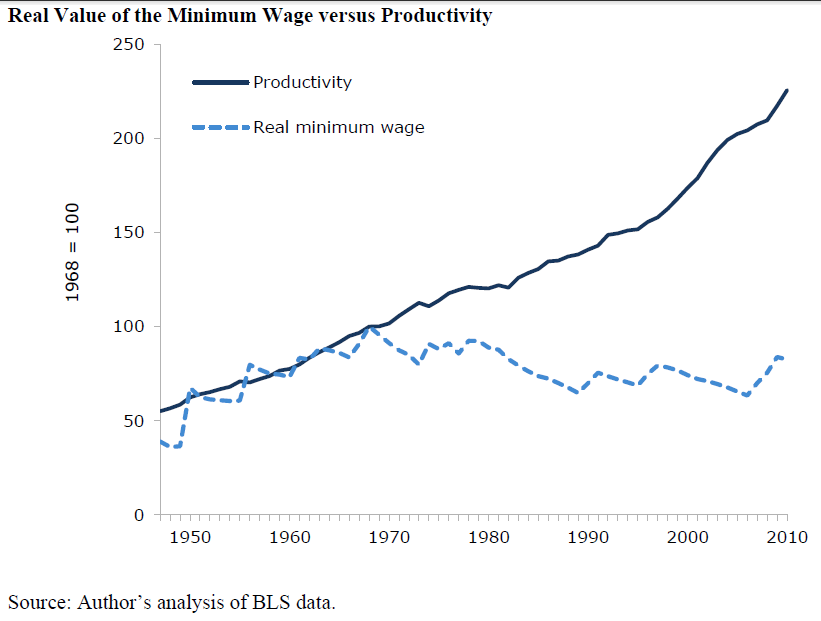

A national minimum wage was established in the United States in 1938 by the Fair Labor Standards Act. Since then, Congress has increased it every few years, although since 1968 it has fallen far behind inflation and productivity growth.

By 2015, over half of the states[2] and many localities will have increased local minimum wages above the federal level. Several major cities, including New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland (California) and San Diego (California), are currently considering raising their wage floors.[3]

Each time such raises are proposed, bitter debates break out over the potential effects. Somehow, though, economic devastation has been repeatedly averted.

History

Historically, the yearly average for recent local minimum wage increases has been 16.7%.[4] But some increases have been far higher. For example, in 1950 the national minimum wage jumped 87.5% from $0.40 to $0.75. And in 2004, the city of Santa Fe, New Mexico, raised its minimum from $5.15 to $8.50, a 65.0% increase.

Even after Santa Fe’s big raise, the average cost increase for all businesses caused by the raise was around one percent. For restaurants, the increase was a little above three percent.[5] The effects may have been so small in part because Santa Fe may have had an unusually low percentage of workers earning close to the old minimum wage.[6]

Santa Fe’s Mayor, David Coss, summed up the experience: “I am proud of Santa Fe’s living wage law. I am also very proud of the businesses in Santa Fe who pay a living wage. Our work on the living wage has made Santa Fe a national leader and has strengthened our economy, community and working families.”[7]

Accounting

The small impact of raising the wage floor may be surprising to those unfamiliar with the historical record. But the accounting is straightforward. Nationally, only 4.3% of all workers earn the federal minimum wage or lower; perhaps two or three times that number would have their wages lifted by a moderate minimum wage hike. All the rest of the workforce would not be affected by the increase.[8]

Among those covered, the average raise will be somewhere around half of the nominal raise from old to new minimum, because most affected workers will have wages somewhere in between. As a result, the total growth in payroll is small for most businesses. And payroll, in turn, averages only about one-sixth of gross revenues for all industries nationally.[9]

These effects, multiplied together, yield very small total increases in costs on the average and for the great majority of businesses.

Employment

Because total cost increases are minimal for most businesses – even in more-affected industries – and can be covered by other adjustments, the loss of low-wage jobs because of moderate minimum wage raises’ has been close to zero. The broad consensus that has emerged from the evidence is that they have no significant effects on employment.[10]

Over the past two decades, the results on the ground of national, state and local increases have been studied intensively using empirical methods that control for other possible influences.

A comprehensive study of state minimum wage increases in the U.S. found “no detectable employment losses from the kind of minimum wage increases we have seen in the United States”, including for the accommodations and food services sector.[11] Two recent meta-studies that analyzed the past two decades of research seconded these findings.[12] Other rigorous economic examinations of minimum wage increases in cities including Santa Fe, San Francisco and San Jose also found no discernable negative effects on employment for low-wage workers.[13]

A study by economists John Schmitt and David Rosnick of the Center for Economic and Policy Research concluded: “The results for fast food, food services, retail, and low-wage establishments in San Francisco and Santa Fe support the view that a citywide minimum wages can raise the earnings of low-wage workers, without a discernible impact on their employment. Moreover, the lack of an employment response held for three full years after the implementation of the measures, allaying concerns that the shorter time periods examined in some of the earlier research on the minimum wage was not long enough to capture the true disemployment effects.”[14]

As Harvard economist Richard Freeman put it, “The debate is over whether modest minimum wage increases have ‘no’ employment effect, modest positive effects, or small negative effects. It is not about whether or not there are large negative effects.”[15]

A letter to the President and Congress signed by 600 economists, including seven Nobel Prize winners, supported raising the national minimum wage to $10.10: “In recent years there have been important developments in the academic literature on the effect of increases in the minimum wage on employment, with the weight of evidence now showing that increases in the minimum wage have had little or no negative effect on the employment of minimum-wage workers, even during times of weakness in the labor market. Research suggests that a minimum-wage increase could have a small stimulative effect on the economy as low-wage workers spend their additional earnings, raising demand and job growth, and providing some help on the jobs front.”[16]

Even The Economist, the influential British neoliberal magazine, recently observed: “No-one who has studied the effects of Britain’s minimum wage now thinks it has raised unemployment.”[17]

Income

In worst cases, some employers may face larger increases in payroll than they can absorb with price increases and increased efficiencies. But even for them, the response will much more likely be to reduce hours slightly than to cut jobs, because laying off and hiring are expensive and disruptive.[18] In such cases, any increase in wages large enough to prompt a reduction in hours would likely be big enough that the paychecks of workers receiving it would still come out ahead.[19]

In many low-wage jobs, hours already fluctuate from week to week, workers frequently change jobs voluntarily or involuntarily, jobs come and go, and businesses start up and fold. For low-wage workers already facing this instability, higher total yearly pay nearly always trumps any loss of yearly hours. In fact, working fewer hours can be a benefit in this case, as it leaves more time for family, training or other work.[20]

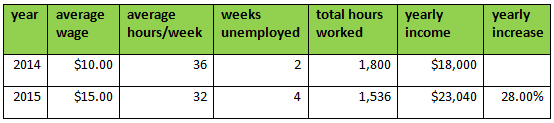

For low-wage workers, employment effects show up primarily in average hours worked weekly and total time out of work yearly. As a hypothetical case, if my hourly wage goes up 50% from $10.00 to $15.00, but my average weekly hours worked drop from 36 to 32 and I’m out of work for 4 weeks instead of 2 weeks, I’m still considerably ahead of the game with a 28.0% increase in my yearly income. If I qualify for unemployment insurance for the weeks out of work, my situation is even better.

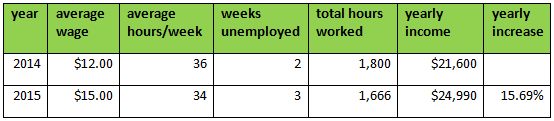

Alternatively, let’s say I’m making $12.00 when my wage rises to $15.00, a 25% increase. Assuming my average weekly hours worked drop from 36 to 34 and I’m out of work for 3 weeks instead of 2 weeks, my yearly income would still be 15.69% higher.

These examples intentionally use improbably large reductions in hours and increases in unemployment, despite strong evidence that cities that have implemented substantial wage increases have seen no significant employment effects.

Ripples

Minimum wage increases do have the effect of compressing the lower part of the pay scale. Those who were making around the old minimum will now be making nearly the same as those who were making near the new minimum. The differences between the lower rungs of the wage ladder will now be much diminished, which may prompt changes in business processes and work relationships.[21]

In this situation, most businesses try to maintain some hierarchy, with the new minimum pushing up the wage levels just above it by small amounts. But this “ripple effect” of small cascading raises adds only a little to total payroll costs.[22] For a 1997 increase of 8% in the federal minimum from $4.75 to $5.15, one study found that workers who had been earning just above the new minimum got a 2% increase (roughly $0.10), and those up to about 10% above the new minimum got a 1% increase (roughly $0.05).[23]

The same study also found that a 2004 increase of 19.4% in the Florida state minimum caused an average cost increase for businesses, from both mandated raises and ripple effects, of less than one-half of 1% of sales revenues. For the hotel and restaurant industry, the average cost increase was less than 1.0%.[24]

The size of ripple raises will depend in part on how important maintaining wage-level distinctions is to employees and employers. It will also be affected by competition from the rest of the low-wage labor market.

Raising the wage floor generally rewards businesses who already pay higher wages towards the bottom of the scale, because minimum wage increases will be a smaller percentage of costs for them. So even contemplating minimum wage legislation could offer incentives to employers to maintain less unequal wage scales.

Exceptions

Only one sector has significantly higher concentrations of low-wage workers and a larger proportion of expenses in payroll: accommodations and food services. It is not a major part of the economy in most places: nationally it accounts for 2.2% of sales, 3.6% of payroll and 10.8% of employment.[25] In these industries, 29.4% of workers are paid within 10% of the minimum wage,[26] and the rule of thumb for restaurant payroll is about one-third of total revenues, twice the overall proportion.

Even for hotels and restaurants, however, larger rises in operating costs are still covered mainly by modest price increases, on the order of 3.2% for a 50% minimum raise by one estimate, and significant reductions in turnover, ranging between 10% and 25% of the costs of raising the wage.[27] Many businesses in this sector have enough flexibility to raise prices without reducing revenues, especially when local competitors all face the same wage increases.[28] They may also be able to raise revenues by increasing sales volume.

In retail, another sector employing some low-wage workers, only 8.8% of the workforce is paid within 10% of the minimum wage.[29] So any minimum wage increase has a much smaller effect on average total costs than in the lodging and food service sector.

Adjustments

In all sectors, lower-wage workers tend to have higher turnover rates, sometimes more than 100 percent annually, yet firing and hiring entail significant costs.[30] Minimum wage increases often help trim these personnel expenses by reducing workforce turnover and absenteeism.[31] The savings, by one estimate, may range from 10% to 25% of the increased payroll costs from raising the minimum.[32]

Businesses may also gain from better-paid and more secure workers becoming more productive. Improvements in business processes and automation can lower expenses and increase quality. And better performance may be required of employees who are now paid higher.[33]

Other possible channels through which businesses can compensate for payroll growth include reductions in benefits or training, changes in employment composition, improvements in efficiency and automation of work processes. Some employers may also accept a small reduction in profits until the wage increases are absorbed.[34]

Even given these multiple channels for adjustment, there are often small businesses and non-profits who find it hard to cover a minimum wage increase – often because they depend heavily on low-wage labor or are unable to raise prices easily. In recognition of this, most local minimum wage increases either exempt smaller firms and non-profits, as in Santa Fe and San Francisco, or phase in increases more slowly for them, as in Seattle.

Stimulus

In the broader economy as well, raising the wage floor may have positive effects. Increased spending prompted by higher wages can stimulate growth in low-wage workers’ neighborhoods.[35]

Rising minimum wages also often reduce government spending on low-income tax credits and poverty programs such as food stamps. Contributions to unemployment insurance, Social Security and Medicare rise with higher incomes. Any positive or negative effects, though, will tend to be small-scale relative to the overall economy.

Given the major positives for low-wage workers and society at large, along with the relatively minor negatives, it is not surprising that nearly all groups with a track record of advocacy for these workers, such as unions, low-income community groups and non-profits serving them, support minimum wage increases.

In an era of secular stagnation and political stalemate, minimum wage increases offer an effective, politically popular, and positively motivating way to reduce income inequality from the bottom up, without reducing low-wage employment.

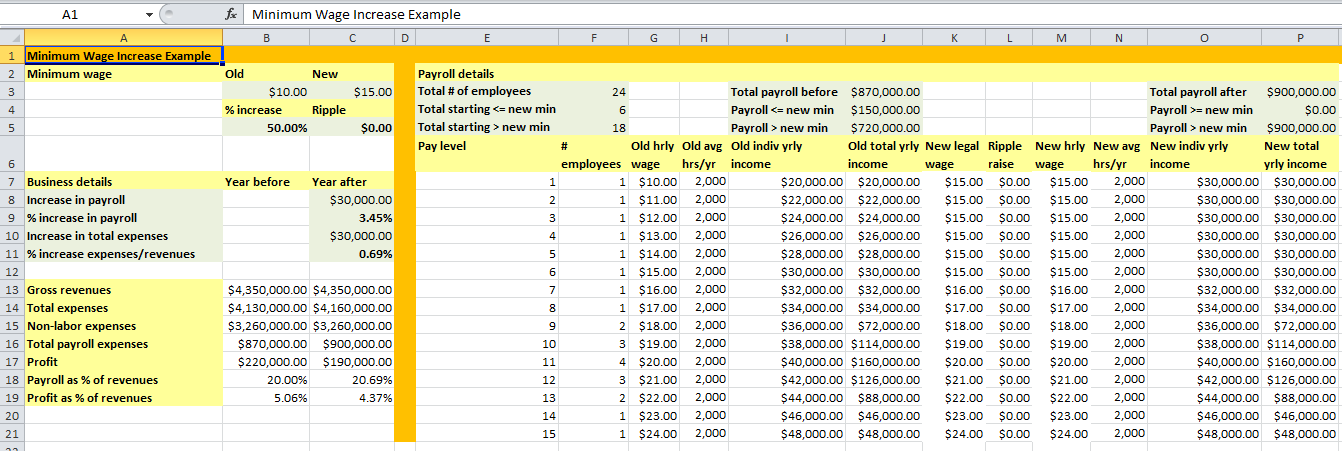

Example: Crunching the numbers for a small business

To get a concrete sense of how raising the wage floor plays out, a little arithmetic goes a long way. Let’s take a hypothetical example of a big raise of 50% in one year, from $10.00 to $15.00.

We’ll zoom in from macro to micro and crunch some simplified numbers for a typical small business that employs 24 workers. Six of them make below or equal to the new minimum: one each makes $10.00, $11.00, $12.00, $13.00, $14.00, and $15.00. The other 18 employees make an average wage of $20.00, and all workers work 2,000 hours per year. The total payroll of this company is 20% of its gross revenues and its profits are 5%.

The average pre-increase wage of the five workers getting a raise is $12.00 per hour, $10.00 through $14.00 divided by five, and their average raise is $3.00. This computes to a 25% – not 50% – average raise for the five covered workers. For the total payroll, this represents an increase of 3.45 percent.

The total impact of a minimum wage increase of 50% on this hypothetical business, then, is to raise its total expenses 0.69% of gross revenues, or less than one percent.

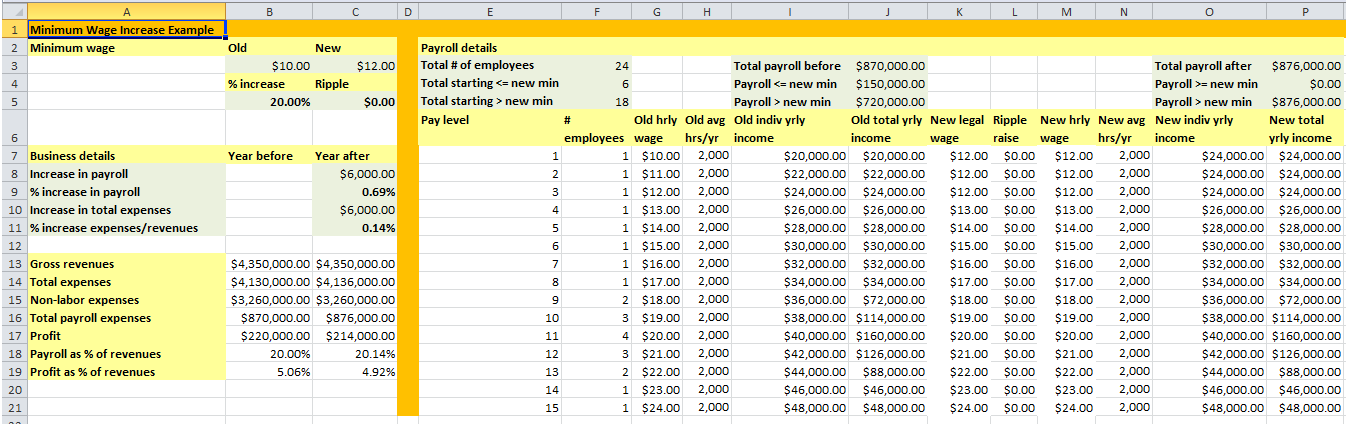

Nationally across all industries, the proportion of payroll to gross revenues is smaller, 16.8 percent[36] rather than 20 percent. And most yearly minimum wage increases have been far less than 50% – an average of 16.7% yearly for local ordinances[37] – so the percentage of affected workers would probably be closer to 10%[38] than 25%. Rounding up, for a 20.0% nominal minimum increase to $12.00 for the same sample payroll, the average for the two workers receiving raises will be 14.3%, yielding a rise in total payroll of 0.69% and in total expenses of 0.14% of gross revenues.

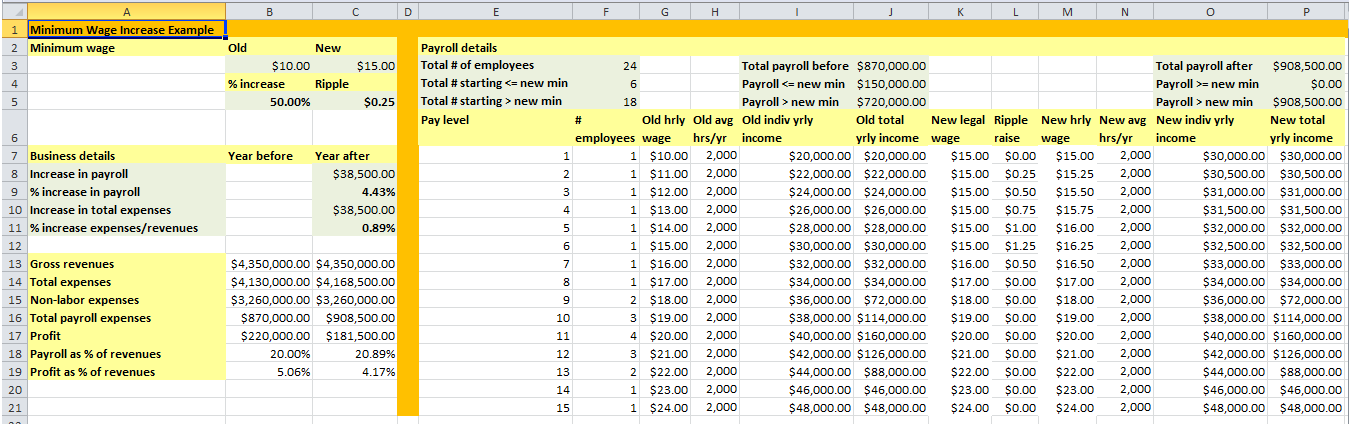

If we factor a ripple effect into our 50%-raise example, spillover wages that keep at least a $0.25 differential between the new levels – $15.00, $15.25, $15.50, etc. – would raise the total payroll increase from 3.23% to 4.43%, and the total increase in business expenses over revenues from 0.69 to 0.89% of gross revenues.

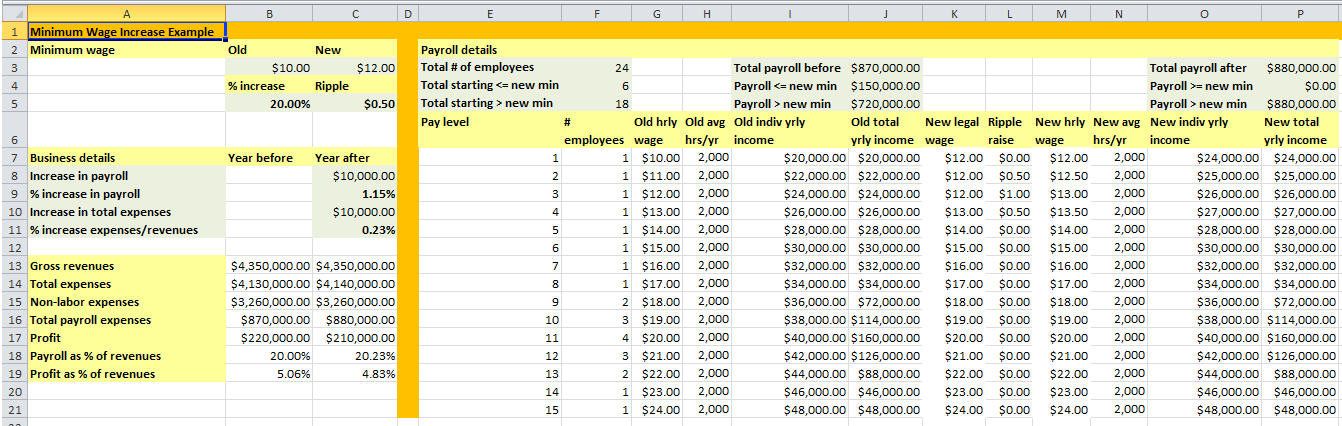

Applying a $0.50 ripple differential to a 20% minimum wage increase for the same data, the total payroll increase would be 1.15% and the total expenses increase would be 0.23% of revenues. We use a lower ripple for the bigger increase because ripple effects tend to be smaller for larger minimum wage increases.[39]

These examples do not take into account many factors such as taxes or benefits. But none of these would appreciably change the big picture of very small cost increases for an average business.

Download zip file of Excel spreadsheets with four examples.

Endnotes

[1] AP 11/19/1956

[2] NELP – What’s the Minimum Wage in Your State?

[3] NELP 5/28/2014. City News Service 4/23/2014.

[4] Reich, Jacobs & Bernhart 3/20/2014, Table 3

[5] Pollin et al

[6] Reich, Jacobs & Bernhart 3/20/2014. Schmitt & Rosnick 3/2011, pp. 28 -30. Potter 8/23/2006. Potter 6/30/2006.

[7] CEPR, 3/22/2011

[8] 23.6% of Seattle workers between $9.32 and $15.00 (60.9% increase) – Klawitter et al. For an increase of 20%, only 7.9% if distribution uniform. Raised estimate to 10 – 12% because Seattle has higher than average wages for U.S. and distribution may be skewed to lower side. Only 4.3% of US workers make the minimum wage – BLS 3/2014.

[9] US Census Bureau 2012, Table 756. Author’s calculation: 16.8%.

[10] Dube, Lester & Reich 11/2010. Schmitt 2/2013.

[11] Dube, Lester & Reich 11/2010, p. 961 – 962

[12] Reich, Jacobs & Bernhart 3/20/2014. Schmitt 2/2013.

[13] Reich 10/2012. San Jose. Schmitt & Rosnick 3/2011. San Francisco & Santa Fe

[14] Schmitt & Rosnick 3/2011

[15] Freeman 1995

[16] Economic Policy Institute 2014

[17] J.P.P (The Economist) 5/3/2014

[18] Schmitt 2/2013, p. 15

[19] Schmitt 2/2013, pp. 17 – 18. Pollin et al 2008, pp. 231 – 232.

[20] Schmitt 2/2013, pp. 17 – 18. Pollin et al 2008, pp. 231 – 232.

[21]

Wicks-Lim 7/2012

[22]

Reich 10/2012. San Jose.

[23] Wicks-Lim 5/2006

[24] Wicks-Lim 5/2006

[25] US Census Bureau 2012, Table 756

[26] Dube, Lester & Reich 11/2010, p. 961

[27] Wicks-Lim 7/2012

[28] Wicks-Lim 7/2012

[29] Dube, Lester & Reich 11/2010, p. 961

[30] Reich 10/2012, p. 8. Boushey & Glynn 11/16/2012. Hirsch, Kaufman & Zelenska 11/2013, pp. 31 – 32.

[31] Wicks-Lim 7/2012. Schmitt 2/2013. Dube, Lester & Reich 7/20/2013, p. 3. Reich, Hall & Jacobs 3/2013.

[32] Wicks-Lim 7/2012

[33] Wicks-Lim 7/2012. Schmitt 2/2013. Hirsch, Kaufman & Zelenska 11/2013.

[34] Schmitt 2/2013. Reich, Jacobs & Bernhart 3/20/2014.

[35] Economic Policy Institute 2014. Reich, Jacobs & Bernhart 3/20/2014, p. 16.

[36] US Census Bureau 2012, Table 756 – author’s calculations

[37] Reich, Jacobs & Bernhart 3/20/2014

[38] 23.6% of Seattle workers between $9.32 and $15.00 (60.9% increase) – Klawitter et al. For an increase of 20%, only 7.9% if distribution uniform. Raised estimate to 10 – 12% because Seattle has higher than average wages for U.S. and distribution may be skewed to lower side.

[39] Wicks-Lim 7/2012

References

Associated Press. “Plan for $1 hourly State Minimum Wage Is Under Attack by Retailers at Hearing”. New York: New York Times, November 19, 1956. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=9805E3D6143BE13BBC4851DFB767838D649EDE

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Characteristics of Minimum Wage Workers 2013”. Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics, March 2014. http://www.bls.gov/cps/minwage2013.pdf

City News Service. “Ballot Measure Would Raise San Diego Minimum Wage To $13”. San Diego, CA: KPBS Public Broadcasting, April 23, 2014. http://www.kpbs.org/news/2014/apr/23/san-diego-council-president-proposes-raising-minim/

Arindrajit Dube, T. William Lester, & Michael Reich. “Minimum Wage Effects Across State Borders: Estimates Using Contiguous Counties”. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Review of Economics and Statistics, November 2010. http://www.irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/157-07.pdf

Economic Policy Institute. “Over 600 Economists Sign Letter In Support of $10.10 Minimum Wage”. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute, 2014. http://www.epi.org/minimum-wage-statement/

Richard Freeman. “What Will a 10% … 50% … 100% Increase in the Minimum Wage Do?”. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 48 (4), 1995. Pp. 830-34.

J.P.P. “The minimum wage: What you didn’t miss”. Washington, DC: The Economist, May 3, 2014. http://www.economist.com/blogs/democracyinamerica/2014/05/minimum-wage

Marieka M. Klawitter, Mark C. Long & Robert D. Plotnick. “Who Would be Affected by an Increase in Seattle’s Minimum Wage?”. Seattle, WA: City of Seattle, Income Inequality Advisory Committee, March 21, 2014. http://www.seattle.gov/council/issues/minimumwage/attachments/UW%20IIACreport.pdf

National Employment Law Project. “What’s the Minimum Wage in Your State?”. New York: National Employment Law Project, accessed July 27, 2014. http://www.raisetheminimumwage.org/pages/minimum-wage-state

National Employment Law Project. “Following Historic Seattle Agreement, Chicago Becomes Next City to Consider $15 Minimum Wage”. New York: National Employment Law Project, May 28, 2014. http://www.raisetheminimumwage.com/media-center/entry/following-historic-seattle-agreement-chicago-becomes-next-city-to-consider-/

Robert Pollin, Mark Brenner, Jeannette Wicks-Lim & Stephanie Luce. A Measure of Fairness: The Economics of Living Wages and Minimum Wages in the United States. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008.

Nicholas Potter. “Earnings and Employment: The Effects of the Living Wage Ordinance in Santa Fe, New Mexico”. Albuquerque, NM: Bureau of Business and Economic Research, University of New Mexico, August 23, 2006. https://bber.unm.edu/pubs/SantaFeEarningsFinalReport.pdf

Nicholas Potter. “Measuring the Employment Impacts of the Living Wage Ordinance in Santa Fe, New Mexico”. Albuquerque, NM: Bureau of Business and Economic Research, University of New Mexico, June 30, 2006. https://bber.unm.edu/pubs/EmploymentLivingWageAnalysis.pdf

Michael Reich. “Increasing the Minimum Wage in San Jose: Benefits and Costs”. Berkeley, CA: Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, University of California, Berkeley, October 2012. http://www.irle.berkeley.edu/cwed/briefs/2012-01.pdf

Michael Reich, Ken Jacobs & Annette Bernhart. “Local Minimum Wage Laws: Impacts on Workers, Families and Businesses”. Seattle, WA: City of Seattle, Income Inequality Advisory Committee, March 2014. http://www.seattle.gov/council/issues/minimumwage/attachments/UC%20Berkeley%20IIAC%20Report%203-20-2014.pdf

John Schmitt. “The Minimum Wage Is Too Damn Low”. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, March 2012. http://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/min-wage1-2012-03.pdf

John Schmitt. “Why Does the Minimum Wage Have No Discernible Effect on Employment?” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, February 2013. http://www.cepr.net/index.php/publications/reports/why-does-the-minimum-wage-have-no-discernible-effect-on-employment

John Schmitt & David Rosnick. “The Wage and Employment Impact of Minimum-Wage Laws in Three Cities”. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, March 2011. http://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/min-wage-2011-03.pdf

The Economist. “Focus: Minimum wage”. London: The Economist, April 16, 2013. http://www.economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2013/04/focus-2

U.S. Census Bureau. “Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012”. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, 2013. https://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0756.pdf

Jeannette Wicks-Lim. “How High Could the Minimum Wage Go?”. Boston, MA: Dollars & Sense, July/August 2012. http://dollarsandsense.org/archives/2012/0712wicks-lim.html

Jeannette Wicks-Lim. “Measuring the Full Impact of Minimum and Living Wage Laws”. Boston, MA: Dollars & Sense, May/June 2006. http://dollarsandsense.org/archives/2006/0506wicks-lim.html

Note: This is an expanded, footnoted version of the article published on June 3, 2014 under the same headline by Inter Press Service.

English: Low-Wage Workers Butt Heads With 21st Century Capital. http://www.ipsnews.net/2014/06/low-wage-workers-butt-heads-with-21st-century-capital

Español: McDonald’s y la lucha por el salario mínimo en EEUU.

Seattle, Washington, United States

Note: This is an expanded, footnoted version of the article published on June 3, 2014 under the same headline by Inter Press Service.

English: Low-Wage Workers Butt Heads With 21st Century Capital. http://www.ipsnews.net/2014/06/low-wage-workers-butt-heads-with-21st-century-capital

Español: McDonald’s y la lucha por el salario mínimo en EEUU. http://www.ipsnoticias.net/2014/06/mcdonalds-y-la-lucha-por-el-salario-minimo-en-eeuu

“Supersize my salary now!” The refrain rose over a busy street outside a McDonald’s in downtown Seattle.

A young African-American mother carrying a little girl told the largely youthful crowd that she had walked off the job to join them because “we’re getting tired of being pushed around”. Her five-year-old took the microphone in both hands with a big grin and led a spirited chant: “We’re fired up, can’t take it no more!”

Green signs sported a hashtag, “Strike poverty 5-15-14 #FastFoodGlobal”, red t-shirts reasoned “Because the rent won’t wait – 15 now”, and a blue banner exhorted “$15 an hour plus tips. Don’t steal our wages.”

A few hundred ethnically diverse demonstrators filled a sunny afternoon with demands that fast-food chains pay a living wage. Dancers gyrated to Aretha Franklin’s ode to “R-E-S-P-E-C-T”. Seattle City Council member Kshama

Sawant said that workers in over 150 cities, including her hometown of Mumbai, India, had walked off their jobs that day.

Fast-food worker Sam Leloo captured the feeling of being trapped by low wages: “I believe in this movement because I’m trying to save enough to go to college and better myself. And I can’t go to college because I don’t make enough money. So it’s a Catch-22.”

According to the organizers, the Seattle event was one link in a chain of actions in over 30 countries by coalitions of grassroots worker centers, labor unions, community groups and faith organizations demanding better wages for fast-food workers.

This prosperous Pacific Northwest seaport, though, is the place in the United States closest to actually raising the minimum wage for all workers to something approaching a living wage. From the current Washington state minimum wage of $9.32 an hour, already the highest in the country, Seattle’s mayor, city council, and a majority of citizens according to some polls all support ratcheting up the wage over 60 percent to $15.00. The debate now centers on how long the ramp-up period should be for different-size businesses and non-profits, whether benefits and tips will be included in the wage, and other implementation details.

Seattle would seem a promising test case for these efforts. Home to aerospace giant Boeing and software powerhouses Microsoft and Amazon, the metropolitan area boasts relatively low unemployment and burgeoning technology jobs with good salaries. The electorate votes heavily Democratic and organized labor wields some influence.

Nationally, President Barack Obama has proposed an increase in the federal minimum wage. Democrats introduced legislation in both houses to raise it from the current $7.25 an hour to $10.10 an hour over two years, and index it to inflation thereafter.[1] Recent national polls show strong support for the raise, even among conservatives.[2] But the proposal was filibustered by Senate Republicans, throwing the initiative back to states and localities.

A national minimum wage was first established in 1938 by the Fair Labor Standards Act. Through 1968, it roughly tracked inflation, median wages and productivity. But sporadic increases since then have failed to keep up with prices, and the inflation-adjusted wage has never returned to its 1968 high. Meanwhile, it has fallen far behind productivity growth: had it kept pace, according to economist John Schmitt of the Center for Economic and Policy

Research, by 2012 it would be nearly three times as high, $21.72 instead of $7.25.[3]

To bypass the federal stalemate, since the 1990s state and local efforts to raise minimum wages have proliferated. In the decentralized U.S. legal system, states and localities can set their own minimum wages, with the highest benchmark applying. Twenty-six of the 50 states have raised or are raising their base wages above the federal level, with increases scheduled in eight states and the District of Columbia.[4] More than 120 cities have also raised their benchmarks,[5] and besides Seattle, efforts are underway in San Francisco, Oakland, Los Angeles, San Diego, Chicago, New York and Portland, Maine.[6]

This resurgent movement to raise the floor of the labor market is surfing the zeitgeist of renewed international debate on economic inequality. “Capital in the Twenty-First Century”, the chef d’oeuvre of French economist Thomas Piketty, has levitated to number one on the New York Times non-fiction bestseller list.[7] Piketty documents “forces of divergence” in modern capitalism driving current levels of wealth concentration unequalled since the 1920s. To remedy some of the “potentially terrifying” consequences of these “long-term dynamics of the wealth distribution”, he proposes a global tax on wealth.[8]

Piketty is no prophet crying in the wilderness. Institutions as influential as the International Monetary Fund and the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank have joined the chorus.

IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde has flagged “rising income inequality” as “a growing concern for policy makers around the world.” Equity along with growth, she has pointed out, are “necessary for stability”, which in turn is “essential for reducing poverty”. The IMF, Lagarde has said, should foster “fiscal policies to reduce poverty” and advance “inclusive” growth.[9] Lagarde previously served as Finance and Economy Minister in the center-right French government of Nicolas Sarkozy and chaired the G-20 for France.[10]

Fed chair Janet Yellen has called “a huge rise in income inequality” going back to the 80s “one of the most disturbing trends facing the nation”.[11]

Both the IMF and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development have recently recognized that moderate minimum wage raises may be beneficial.[12]

As a non-fiscal means of raising the ground floor of the income pyramid, minimum wage hikes have proved attractive even to some conservatives, in part because they do not require direct outlays by cash-strapped governments.

The Economist magazine, a British champion of market hegemony, has swung from opposition to grudging acceptance that measured minimum wage increases can do more good than harm.[13] Another business-friendly voice, the U.S. news service Bloomberg, has editorialized in favor of raising the national minimum.[14]

Conservative British Finance Minister George Osborne recently advocated an increase in the U.K. base wage.[15] And center-right Chancellor Angela Merkel approved Germany’s first minimum wage legislation in April. Pending parliamentary ratification, the benchmark will be set at 8.50 euros (US$ 11.75) in 2015.[16]

Compared to other wealthy countries, working for the Yankee dollar pays poorly at the low end. The U.S. minimum wage of $7.25 was a miserly 38.3 percent of its 2012 median wage. Britain’s ratio was 46.7 percent, slightly above the European Union average, while France led with a minimum 60.1 percent of its median. Of major industrialized nations, only Japan, at 38.4 percent, had a percentage of median nearly as low as the U.S. one.

As the minimum wage in much of the United States falls ever farther behind the economy, labor-market and demographic undertows have constrained increasingly older and more-educated workers to take low-wage jobs.

In 1979, 26 percent of low-wage workers (making $10 an hour or less in 2011 dollars) were under 20 years old, 39.5 percent had less than a high-school diploma, and 25.2 percent had some university or a university degree. By 2011, only 12 percent were under 20 and 19.8 percent had completed less than high school, a drop of roughly one-half for each measure. The proportion with at least some college had grown to 43.2 percent, an increase of more than two-thirds. Fifty-five percent of minimum wage workers were women, and 43 percent were people of color, both above their respective proportions in the U.S. workforce.[17]

The stereotype of low-wage workers as mainly high-school kids earning extra pocket money, never very accurate, has been made obsolete by decades of economic tsunamis washing away better-paying manufacturing jobs.

Nevertheless, some politicians and business groups confront each proposed minimum wage increase with stern warnings that it will destroy jobs. Historically, though, the predicted damage has yet to materialize.

After decades of experience, rigorously empirical studies have consistently found no significant effects on employment due to minimum wage increases at national, state or local levels. Increased costs to businesses have been absorbed mainly through very small price increases, averaging on the order of one percent for all affected businesses. Food, hospitality and a few other industries that use more low-wage labor have tended to increase prices slightly more, but rarely more than an average of three percent.[18]

Other means of reducing costs have included increased productivity through lower turnover and absenteeism, better organizational efficiency, increase automation, compression of the wage scale, and sometimes slightly reduced average hours.[19]

These trends held even for Santa Fe, New Mexico, after its 65 percent minimum wage hike in 2004, the biggest local raise. There, increased expenses against revenues averaged around one percent for all affected businesses. The restaurant and hotel industries had average cost increases of three to four percent. To cover these, a $10.00 meal would have had to rise to $10.35.[20]

In any case, the pertinent question is not whether any jobs are lost: it is whether affected workers end up better off after the increase.

Unlike the high-school-to-Social-Security factory jobs of a half-century ago, today’s low-wage service jobs are notoriously volatile. Turnover is often high, with workers leaving involuntarily as businesses fail or cut labor forces, or voluntarily to seek better jobs. Weekly hours also frequently fluctuate with business conditions. From a worker’s point of view, a “lost job” usually translates into days or weeks until the next job, not a life-changing

loss.

After previous minimum wage increases, even if total hours worked yearly were reduced slightly for some workers, the size of the hourly raise has nearly always ensured that their total yearly income was higher than before the increase.[21]

Back at the Seattle rally, Council Member Sawant, elected on a platform that highlighted raising the city’s minimum wage to $15 an hour, preached to the choir: “Because of our courage, our solidarity with each other, not because of the powers that be, we have brought things to this point where fifteen can become a reality in Seattle and inspire the whole nation and the whole world.”

Endnotes

[1]S.460 and H.R. 1010

[2]Pew Research Center for the People & the Press 3/4/2014; Washington Post/ABC 4/28/2014

[3]Schmitt 3/2012

[4]Sahadi 4/28/2014

[5]Adams 5/3/2014

[6]Sahadi 4/28/2014

[7]Arcega 5/16/2014

[8]Cassidy 3/31/2014

[9]Lagarde 11/15/2013

[10]IMF 11/14/2013

[11]Covert, 11/15/201; Chandra, 5/20/2014

[12]J.P.P. 5/3/2014

[13]J.P.P. 5/3/2014

[14]Bloomberg, 4/16/2012

[15]J.P.P. 5/3/2014

[16]BBC 12/14/2013

[17]Schmitt & Jones 4/2012

[18] Pollin et al 2008; Schmitt 2/2013

[19] Pollin et al 2008; Schmitt 2/2013; Dube et al 11/2010

[20] Pollin et al 2008; Schmitt 2/2013; Dube et al 11/2010

[21] Pollin et al 2008; Schmitt 2/2013

References

Susan Adams. “Why The Minimum Wage Will Go Up”. New York: Forbes Magazine, May 6, 2014.

http://www.forbes.com/sites/susanadams/2014/05/06/why-the-minimum-wage-will-go-up/

Mil Arcega. “Income Inequality Drives Economic Book Into US Best-Seller List”. Washington, DC: Voice of America, May 16, 2014. http://www.voanews.com/content/income-inequality-drives-economic-book-into-us-best-seller-list/1916494.html

Dean Baker. “Robert Samuelson’s Arithmetic Challenged Economics”. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, Feb. 23, 2014. http://www.cepr.net/index.php/blogs/beat-the-press/robert-samuelsons-arithmetic-challenged-economics

Dean Baker & Will Kimball. “The Minimum Wage and Economic Growth”. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, Feb. 12, 2013. http://www.cepr.net/index.php/blogs/cepr-blog/the-minimum-wage-and-economic-growth

BBC News. “Angela Merkel approves Germany’s first minimum wage”. London: BBC News, April 2, 2014. http://www.bbc.com/news/business-26851906

Bloomberg. “Raise the Minimum Wage”. New York: Bloomberg.com, April 16, 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-04-16/u-s-minimum-wage-lower-than-in-lbj-era-needs-a-raise.html

John Cassidy. “Forces of Divergence”. The New Yorker, March 31, 2014. http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/books/2014/03/31/140331crbo_books_cassidy

Shobhana Chandra. “Lower-Rung US Workers Get Leg Up in Bankers’ View Economy”. New York: Bloomberg, May 20, 2014.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-05-20/lower-rung-workers-get-leg-up-in-goldman-s-view-as-u-s-grows.html

Bryce Covert. “Federal Reserve Chair Nominee Income: Inequality Is ‘A Very Serious Problem’”. ThinkProgress, November 15, 2013. http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2013/11/15/2947861/federal-reserve-janet-yellen-income-inequality

Arindrajit Dube, T. William Lester, and Michael Reich. “Minimum Wage Effects Across State Borders: Estimates Using Contiguous Counties”. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Review of Economics and Statistics, November 2010. http://www.irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/157-07.pdf

International Monetary Fund. “Christine Lagarde, Eleventh Managing Director of IMF – Biographical Information”. International Monetary Fund, November 14, 2013. http://www.imf.org/external/np/omd/bios/cl.htm

Christine Lagarde. “Stability and Growth for Poverty Reduction” (speech). Washington, DC: Bretton Woods Committee 2013 Annual Meeting, May 15, 2013. http://www.imf.org/external/np/speeches/2013/051513.htm

J.P.P. “The minimum wage: What you didn’t miss”. Washington, DC: The Economist, May 3, 2014. http://www.economist.com/blogs/democracyinamerica/2014/05/minimum-wage

Pew Research Center for the People & the Press. “Polls show strong support for minimum wage hike”. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, March 4, 2014.http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/03/04/polls-show-strong-support-for-minimum-wage-hike

Robert Pollin, Mark Brenner, Jeannette Wicks-Lim & Stephanie Luce. A Measure of Fairness: The Economics of Living Wages and Minimum Wages in the United States. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008.

Jeanne Sahadi. “Minimum wage: Congress stalls, states act”. New York: CNN Money, April 28, 2014.http://money.cnn.com/2014/04/28/news/economy/states-minimum-wage/index.html

John Schmitt. “The Minimum Wage Is Too Damn Low”. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, March 2012. http://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/min-wage1-2012-03.pdf

John Schmitt. “Why Does the Minimum Wage Have No Discernible Effect on Employment?” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, February 2013. http://www.cepr.net/index.php/publications/reports/why-does-the-minimum-wage-have-no-discernible-effect-on-employment

John Schmitt & Janelle Jones. “Low-wage Workers Are Older and Better Educated than Ever”. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, April 2012. http://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/min-wage3-2012-04.pdf

In reporting on economic issues, numbers often lie.

Well, OK, let’s not blame the numbers themselves. Let’s not even assume that the intent of those who deploy them is to deceive.

We’re still facing a pervasive problem: numbers and especially dollar figures without context – the fraction of the larger numbers of which [...]]]>

In reporting on economic issues, numbers often lie.

Well, OK, let’s not blame the numbers themselves. Let’s not even assume that the intent of those who deploy them is to deceive.

We’re still facing a pervasive problem: numbers and especially dollar figures without context – the fraction of the larger numbers of which they are a part, and the time period over which they apply – leave most consumers of economic reporting without points of reference in understanding what these numbers mean.

In that weakened condition, zerophobia, which often manifests as an involuntary rapid intake of breath sometimes followed by expletives inspired by large numbers of zeroes following a dollar sign, can lead stricken citizens to misunderstand the import of quantities central to economic issues.

Quick, how big is the total budget of the City of Seattle? I doubt many of the Seattle Times’ readers can answer that off the cuff. But the otherwise informative story it published January 28, “$1M price tag tied to paying Seattle city workers $15/hr”, seems to assume that most readers know that figure. Otherwise, how would they have any idea whether $1 million is a lot or a little relative to city expenditures? They need a fraction or percentage to put it in some larger context.

For the record, the total 2014 budget of the City of Seattle is $4.4 billion. That makes the cost of the minimum wage increase 1/4,400, or 0.023 percent, of the budget. As the piece reports, the city believes it can cover that mostly from increases in general fund revenues due to the growing economy.

Another way to report this sort of figure would be the cost per capita to Seattleites. For an estimated 2013 population of 626,600, the $1 million dollars compute out to $1.60 per person per year.

In evaluating Mayor Ed Murray’s proposal to pay all city employees at least a $15 minimum wage, it would also be nice to know a related economic effect: the multiplier created by the increase. How much further economic activity and tax revenue will be generated by city employees spending their wage increases?

Of course this is not just a local Seattle problem. Economist Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy Research has raised the profile of this issue nationally and internationally. CEPR offers a budget calculator that can help put numbers in the context of the total Federal budget. In response to him and other critics, Margaret Sullivan, the New York Times Public Editor, has acknowledged the need to make the economic figures it reports clearer and more meaningful.

Zerophobia can be cured. It need not condemn sufferers to a lifetime of economic cluelessness. With the caring support of fellow sources, journalists, editors and readers, afflicted citizens can recover and make valuable contributions to public discourse once again.

References

Dean Baker. “Mindless Budget Reporting: Fooling Some of the People All of the Time”. Washington, DC: CEPR, August 14, 2013. http://www.cepr.net/index.php/blogs/cepr-blog/mindless-budget-reporting-fooling-some-of-the-people-all-of-the-time

Dean Baker with Paul Solman. “Mindless Budget Reporting: Fooling Some of the People All of the Time”. Washington, DC: PBS Newshour, August 14, 2013. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/making-sense/mindless-budget-reporting-fool/

Center for Economic and Policy Research. “The CEPR Budget Calculator”. Washington, DC. Accessed Feb. 14, 2014. http://www.cepr.net/calculators/calc_budget.html

Center for Economic and Policy Research. “Responsible Budget Reporting”. Washington, DC. Accessed Feb. 14, 2014. http://www.cepr.net/index.php/responsible-budget-reporting

City of Seattle – 2014 Proposed Budget Executive Summary. Accessed Feb. 14, 2014. http://www.seattle.gov/financedepartment/14proposedbudget/documents/OVERVIEW.pdf

City of Seattle – Population & Demographics (web site). Accessed Feb. 14, 2014. http://www.seattle.gov/dpd/cityplanning/populationdemographics/default.htm

Margaret Sullivan. “The Times Is Working on Ways to Make Numbers-Based Stories Clearer for Readers”. New York Times, Public Editor’s Journal, October 18, 2013. http://publiceditor.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/10/18/the-times-is-working-on-ways-to-make-numbers-based-stories-clearer-for-readers/?ref=thepubliceditor

Lynn Thompson. “$1M price tag tied to paying Seattle city workers $15/hr”. Seattle Times, January 27, 2014. http://seattletimes.com/html/localnews/2022771198_15cityemployeesxml.html

]]>