by Jim Lobe

A Guatemalan court this afternoon found former President Efrain Rios Montt guilt of genocide and crimes against humanity committed against the indigenous Mayan Ixil population as a result of the counter-insurgency campaign he directed as president from 1982 to 1983; that is, in the middle of Elliott [...]]]>

by Jim Lobe

A Guatemalan court this afternoon found former President Efrain Rios Montt guilt of genocide and crimes against humanity committed against the indigenous Mayan Ixil population as a result of the counter-insurgency campaign he directed as president from 1982 to 1983; that is, in the middle of Elliott Abrams’ tenure as the Reagan administration’s assistant secretary of state for human rights. While human rights, church groups, and the American Anthropological Association repeatedly denounced that campaign (with some actually calling it “genocide”), the administration moved during that period to restore and increase military aid to the government. In fact, after visiting personally with Rios Montt in Honduras in early December, 1982, Reagan himself declared that the born-again president was getting a “bum rap” from rights groups and journalists and that he was “a man of great personal integrity” who faced “a brutal challenge from guerrillas armed and supported by others outside Guatemala.”

Here’s what Human Rights Watch, with which Abrams clashed quite frequently over rights conditions in Central America, including Guatemala, during Rios Montt’s reign, said tonight after the verdict was announced:

Guatemala: Rios Montt Convicted of Genocide

Landmark Ruling against Impunity, Judicial Control Needed in Handling Appeals

(New York, May 10, 2013)—The guilty verdict against Efraín Ríos Montt, former leader of Guatemala, for genocide and crimes against humanity is an unprecedented step toward establishing accountability for atrocities during the country’s brutal civil war, Human Rights Watch said today.

“The conviction of Rios Montt sends a powerful message to Guatemala and the world that nobody, not even a former head of state, is above the law when it comes to committing genocide,” said José Miguel Vivanco, Americas director at Human Rights Watch. “Without the persistence and bravery of each participant in this effort – the victims, prosecutors, judges, and civil society organizations – this landmark decision would have been inconceivable.”

Rios Montt was sentenced to 50 years in prison for the crime of genocide and 30 years for crimes against humanity in a sentence that was handed down on May 10, 2013 by Judge Yassmin Barrios in Guatemala City. In her decision, Barrios said Rios Montt was fully aware of plans to exterminate the indigenous Ixil population carried out by security forces under his command.

The genocide conviction was the first for a current or former head of state in a national court, Human Rights Watch said.

Clearly, tonight’s conviction should prove rather embarrassing for Abrams, as this genocide occurred “on his watch,” so to speak, and there’s no on-the-record indication that he ever disagreed with the defense that the administration mounted on Rios Montt’s behalf or that he opposed its repeated efforts to provide Guatemala’s army with military aid. Nor, of course, did Abrams resign in protest over those efforts.

Precisely what his stance vis-a-vis Guatemala policy was during this period remains somewhat cloudy, as the American Republic Affairs (ARA) bureau, then led by the late Tom Enders (the man who oversaw the secret bombing of Cambodia), was the main public spokesman for the administration’s policy. Hopefully, the National Security Archive, whose dogged work played a major role in making Rios Montt’s prosecution possible, will soon release declassified documents that will shed light on what Abrams did or did not do on Guatemala during this period and specifically whether he signed off on/objected to/tried to amend testimony and other public statements made by Enders and other officials. (It would be very interesting to find out whether he may have, as the chief human rights official, personally briefed Reagan before the “bum rap” statement.)

For example, after Amnesty International issued a searing report detailing 112 incidents in which from one to 100 men, women and children were reportedly massacred by Guatemalan troops, Enders sent a letter to Congress contesting the findings, noting, among other things, that Amnesty had relied on groups “closely aligned with, if not largely under the influence of, the guerrilla groups attempting to overthrow the Guatemalan government.” His letter was based on an unpublished memorandum from the U.S. embassy in Guatemala which, among other assertions, concluded that “a concerted disinformation campaign is being waged in the US against the Guatemalan Government by groups supporting the leftwing insurgency in Guatemala; this has enlisted the support of conscientious human rights and church organizations which may not fully appreciate that they are being utilized.”

At about the same time, Enders’ principal deputy, Stephen Bosworth, testified before the House Subcommittee on International Development — the administration was moving to increase balance-of-payments support to Rios Montt and lift Carter-era, human rights-related bans on U.S. support for loans from the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank — that Rios Montt was doing great things for the native population in the Ixil Triangle:

Political violence in rural areas continues and may even be increasing, but its use as a political tactic appears to be a guerrilla strategy, not a government doctrine. Eyewitness reports of women among the attackers, Embassy interviews with massacre survivors, the use of weapons not in the army inventory, and most importantly, the increasing tendency of rural villagers to seek the army’s protection all suggest that the guerrillas are responsible in major part for the rising levels of violence in rural areas.

Given what we have learned about Rios Montt’s “Beans-and-Bullets” strategy, these assertions today seem utterly laughable, if the actual events were not so terrible.

But the question remains: what was Abrams doing during this period about Guatemala. Did he review the embassy report? Did he clear Enders’ letter or Bosworth’s testimony? Was he — by all accounts, an effective bureaucratic infighter — in the loop while this genocide was taking place and the administration was pushing hard to arm the genocidaires? (We know his office received this cable.) How did he respond?

Rios Montt’s conviction may prove embarrassing not only to Abrams, but also to some of his fellow-neocons who also defended Guatemala during this period. Here’s the Wall Street Journal celebrating Reagan’s blessing as a “Guatemalan Breakthrough” (Dec 15, 1982):

Change in Guatemala would vindicate the Reagan administration’s much maligned human rights policy. Unlike the Carter administration’s confrontational posturing, the quiet argument of Reagan’s men seems to be finding an audience. Much of the changed atmosphere is undoubtedly due to the coup that installed General Rios Montt, a born-again evangelical Christian. The early promise of Rios Montt’s rule was tarnished by reports of massacres of Indians and of renewed “death squad” activity. But perhaps General Rios Montt had recognized the key point — that human rights not only make moral sense but also are the only practical base on which to build a legitimate government.

Thus General Rios Montt seems to have ordered his troops in the field to observe strict rules not to molest or steal from peasants, borrowing a page from the guerrilla textbook. At the same time, the peasants are being encouraged to join government forces in return for food and shelter, thus denying a source of manpower to the guerrillas.

Doubtless the Rios Montt approach also owes something to the way the Reagan administration is handling human rights. An absolute insistence on every detail of the most advanced democracy can prove devastating to our authoritarian friends.

Sounds a little naive in retrospect, doesn’t it?

Also likely to be somewhat embarrassed is the government of Israel which moved into the vacuum created by Carter’s and Congress’s cut-off of military and intelligence assistance and subsequently expanded its involvement with Rios Montt’s counter-insurgency efforts with the Reagan administration’s encouragement. In 1982, just before Reagan’s visit, Ríos Montt told ABC News that his success in allegedly defeating the guerrillas was due the fact that “our soldiers were trained by Israelis.” It was the same year as the Sabra and Shatila massacres by Israel-backed Phalange militiamen in Beirut. Now, its Central American client has been convicted of genocide.

]]>Considering the misleading claims made about non-existent Iraqi and Iranian nuclear weapons, and the ramifications of another costly and catastrophic war, there should be more analyses like Scott Peterson’s highlighting of lessons from the lead-up to the 2003 US invasion of Iraq.

A declassified January 2006 report published in [...]]]>

Considering the misleading claims made about non-existent Iraqi and Iranian nuclear weapons, and the ramifications of another costly and catastrophic war, there should be more analyses like Scott Peterson’s highlighting of lessons from the lead-up to the 2003 US invasion of Iraq.

A declassified January 2006 report published in September by the indispensable National Security Archive shows that CIA analysts allowed their search for non-existent Iraqi weapons of mass destruction to overshadow Saddam Hussein’s reasons for bluffing about them. Peterson accordingly suggests that Iranian attempts to eradicate traces of what appears to be previous weapons work (halted in 2003, according to the 2007 NIE), could be a face-saving measure rather than evidence of malicious intent. Increasing “scrutiny and distrust” directed at Iraq also led to counterproductive activities from both sides:

But that Iranian refusal – while at the same time engaging in “substantial” landscaping of the site, which the IAEA says undermines its ability to inspect it for traces of past nuclear work – echoes many Iraqi weapons inspections in the 1990s. In those standoffs, Iraqi officials often behaved as if they had something to hide, when in fact they did not.

As the CIA’s 2006 assessment states, “Iraq’s intransigence and deceptive practices during the periods of UN inspections between 1991 and 2003 deepened suspicions … that Baghdad had ongoing WMD programs.”

The CIA further notes that Iraqi attempts “to find face-saving means to disclose previously hidden information” meant that Iraqi attempts later to “close the books” only “reinvigorated the hunt for concealed WMD, as analysts perceived that Iraq had both the intent and capability to continue WMD efforts.…”

This led Iraq to one conclusion, similar to the public declarations of Iranian leaders today: “When Iraq’s revelations were met by added UN scrutiny and distrust, frustrated Iraqi leaders deepened their belief that inspections were politically motivated and would not lead to the end of sanctions,” read the CIA report.

Some analysts have dared to suggest that Iranian attempts to remove traces of halted weapons work is ultimately a positive sign. Consider the assessment of MIT international security expert Jim Walsh, who focuses on Iran’s nuclear program, talking about Parchin last week at a conference in Washington last week:

]]>So I think they had a weapons program; they shut it down. I think part of what was happening was at Parchin, this gigantic military base that the IAEA visited, but because it’s so large, they went to this building and not that building and that sort of thing. Then they get – IAEA gets some intel that says, well, we think the explosives work was being done in this building, and, you know, all this time, Iran’s being – Parchin’s being watched by satellites continuously, and there’s no activity there. Nothing for five years, right? And then – or – not five years, but some period of time – years.

So then, the IAEA says, well, we want to go to that building, and then suddenly, there’s a whole lot of activity. You know, there’s cartons put up and shoveling and scalping of soil and all that sort of thing. So I read this as – that was a facility involved in the bomb program, and they’re cleaning it up, and IAEA is not going to get on the ground until it’s cleaned up. Now here’s the part where I’m practical and blunt – I don’t care. Right? This is part of a program from the past. And I wish they didn’t have the program from the past, but I’m more worried about Iran’s nuclear status in the future than the past, and so, you know, if it’s dead, and all they’re doing is cleaning it up so there’s no evidence of what they did before, I – you know, it’s regretful and blah, blah, but I don’t care. I would rather get a deal that prevents Iran from moving forward towards a nuclear weapon or moving forward so that we don’t have a military engagement that leads to a nuclear weapons decision by Iran.

via IPS News

NEW YORK, Nov 26 2012 (IPS) - I have never read a book quite like this. “Becoming Enemies” is the latest product of the indispensable National Security Archive, the Washington non-profit that has given new meaning to the Freedom of Information Act.

They not only use their [...]]]>

via IPS News

NEW YORK, Nov 26 2012 (IPS) - I have never read a book quite like this. “Becoming Enemies” is the latest product of the indispensable National Security Archive, the Washington non-profit that has given new meaning to the Freedom of Information Act.

NEW YORK, Nov 26 2012 (IPS) - I have never read a book quite like this. “Becoming Enemies” is the latest product of the indispensable National Security Archive, the Washington non-profit that has given new meaning to the Freedom of Information Act.

They not only use their skills to get major U.S. policy documents declassified, but they take those documents and find innovative ways to illuminate important historical episodes. This book is a living example.

It covers the period of the Iran-Iraq war, during which U.S.-Iran relations hardened into the seemingly permanent enmity that has characterised their relations ever since. NSA assembled a group of individuals who were deeply involved in the making of U.S. policy during that time, backed up by a small group of scholars who had studied the period.

They provided them with a briefing book of major documents from the period, mostly declassified memos, to refresh their memories, and then launched into several days of intense and structured conversation. The transcript of those sessions, which the organisers refer to as “critical oral history”, is the core of this book.

No one can emerge from this book without a sense of revelation. No matter how much you may know about these tumultuous years, even if you were personally involved or have delved into the existing academic literature, you will discover new facts, new interpretations, and new dimensions on virtually every page.

I say this as someone who was part of the U.S. decision-making apparatus for part of this time and who has since studied it, written about it, and taught it to a generation of graduate students. I found little to suggest that my own interpretations were false, but I found a great deal that expanded what I knew and illuminated areas that previously had puzzled me. I intend to use it in my classes from now on.

Iranians tend to forget or to underestimate the impact of the hostage crisis on how they are perceived in the world. Many Iranians are prepared to acknowledge that it was an extreme action and one that they would not choose to repeat, but their inclination is to shove it to the back of their minds and move on.

This book makes it blindingly clear that the decision by the Iranian government to endorse the attack on the U.S. embassy in November 1979 and the subsequent captivity of U.S. diplomats for 444 days was an “original sin” in the words of this book for which they have paid – and continue to pay – a devastating price.

Similarly, U.S. citizens tend to forget their casual response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Iran, our tacit acquiescence to massive use of chemical weapons by Iraq, and the shootdown of an Iranian passenger plane by a U.S. warship, among other things.

The authors of “Becoming Enemies” remind us that, just as Americans have not forgotten the hostage crisis, Iranians have neither forgotten or forgiven America’s own behaviour – often timid, clumsy, incompetent, or unthinking; but always deadly from Iran’s perspective.

It is impossible in a brief review to catalogue the many new insights that appear in this book for the first time. However, one of the most impressive sections deals with the so-called Iran-contra affair – the attempt by the Reagan administration to secretly sell arms to Iran in the midst of a war when we were supporting their Iraqi foes.

This, of course, exploded into a major scandal that revealed criminal actions by many of the administration’s top aides and officials and nearly resulted in the impeachment of the president. The official position of the administration in defending its actions was that this represented a “strategic opening” to Iran.

Participants in this discussion, some of whom had never before publicly described their own roles, dismissed that rationale as self-serving political spin. President Reagan, they agreed, was “obsessed” (the word came up repeatedly) with the U.S. hostages in Lebanon and was willing to do whatever was required to get them out, even if it cost him his job.

Moreover, the illegal diversion of profits from Iran arms to support the contra rebels in Central America was, it seems, only one of many such operations. The public focus on Iran permitted the other cases to go unexamined.

Another striking contribution is the decisive role played by the U.N. secretary-general and his assistant secretary, Gianni Picco (a participant), in bringing an end to the Iran-Iraq war. This is a gripping episode in which the U.N. mobilised Saddam’s Arab financiers to persuade him to stop the war, while ignoring the unhelpful interventions of the United States. They deserved the Nobel Peace Prize they received for their efforts.

There are, however, some lapses in this otherwise exceptional piece of research. One of the “original sins” of U.S. policy that are discussed is the U.S. failure to denounce the Iraqi invasion of Iran on Sep. 22, 1980, thereby confirming in Iranian eyes U.S. complicity in what they call the “imposed war”. I am particularly sensitive to the fact that the discussion of the actions of the Carter administration in 1980 is conducted in the absence of anyone who was actually involved.

Those of us in the White House at the time would never have failed to recall that direct talks with the Iranians about the release of the hostages had begun only days earlier. So there was for the first time in nearly a year a high-level authentic negotiating channel with Iran.

My own contribution to the missed opportunities that are enumerated at the end of the book would, in retrospect, have been our lack of courage or imagination to use our influence with the United Nations Security Council to bargain with Iran for immediate action on the hostages. If we had taken a principled position calling for an immediate cease-fire and Iraqi withdrawal, the entire nature of the war could have been transformed.

To my surprise, Zbigniew Brzezkinski, my boss at the time, sent a personal memo to President Carter (which I had never seen until now) that argued for “Iran’s survival” and held out the possibility of secret negotiations with Tehran. This was a total revelation to me, and it was so contrary to the unfortunate conventional wisdom that Brzezkinski promoted the Iraqi invasion that even the authors of this book seemed at a loss to know what to make of it.

The other huge disappointment with this initiative, which is not the fault of the organisers, was the absence of any Iranian policymakers. Iranian leaders and scholars should read this book. Perhaps one day their domestic politics will permit them to enter into such a dialogue. That day is long overdue.

*Gary Sick is a former captain in the U.S. Navy, who served as an Iran specialist on the National Security Council staff under Presidents Ford, Carter, and Reagan. He currently teaches at Columbia University. He blogs at http://garysick.tumblr.com.

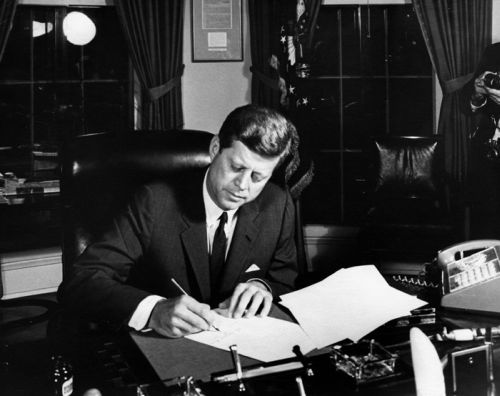

]]>It was exactly 50 years ago when then-President John F. Kennedy took to the airwaves to inform the world that the Soviet Union was introducing nuclear-armed missiles into Cuba and that he had ordered a blockade of the island – and would consider stronger action – to force their removal.

[...]]]> It was exactly 50 years ago when then-President John F. Kennedy took to the airwaves to inform the world that the Soviet Union was introducing nuclear-armed missiles into Cuba and that he had ordered a blockade of the island – and would consider stronger action – to force their removal.

It was exactly 50 years ago when then-President John F. Kennedy took to the airwaves to inform the world that the Soviet Union was introducing nuclear-armed missiles into Cuba and that he had ordered a blockade of the island – and would consider stronger action – to force their removal.

“It was the most chilling speech in the history of the U.S. presidency,” according to Peter Kornbluh of the National Security Archive, who has spent several decades working to declassify key documents and other material that would shed light on the 13-day crisis that most historians believe brought the world closer to nuclear war than at any other moment.

Indeed, Kennedy’s military advisers were urging a pre-emptive strike against the missile installations on the island, unaware that some of them were already armed.

Several days later, the crisis was resolved when Soviet President Nikita Krushchev appeared to capitulate by agreeing to withdraw the missiles in exchange for a U.S. pledge not to invade Cuba.

“We’ve been eyeball to eyeball, and the other fellow just blinked,” exulted Secretary of State Dean Rusk in what became the accepted interpretation of the crisis’ resolution.

“Kennedy’s victory in the messy and inconclusive Cold War naturally came to dominate the politics of U.S. foreign policy,” write Leslie Gelb, president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations in a recent foreignpolicy.com article entitled “The Myth That Screwed Up 50 Years of U.S. Foreign Policy.”

“It deified military power and willpower and denigrated the give-and-take of diplomacy,” he wrote. “It set a standard for toughness and risky dueling with bad guys that could not be matched – because it never happened in the first place.”

What the U.S. public didn’t know was that Krushchev’s concession was matched by another on Washington’s part as a result of secret diplomacy, conducted mainly by Kennedy’s brother, Robert, and Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin.

Indeed, in exchange for removing the missiles from Cuba, Moscow obtained an additional concession by Washington: to remove its own force of nuclear-tipped Jupiter missiles from Turkey within six months – a concession that Washington insisted should remain secret.

“The myth (of the Cuban missile crisis), not the reality, became the measure for how to bargain with adversaries,” according to Gelb, who interviewed many of the principals.

Writing in a New York Times op-ed last week, Michael Dobbs, a former Washington Post reporter and Cold War historian, noted that the “eyeball to eyeball” image “has contributed to some of our most disastrous foreign policy decisions, from the escalation of the Vietnam War under (Lyndon) Johnson to the invasion of Iraq under George W. Bush.”

Dobbs also says Bush made a “fateful error, in a 2002 speech in Cincinnati when he depicted Kennedy as the father of his pre-emptive war doctrine. In fact, Kennedy went out of his way to avoid such a war.”

To Graham Allison, director of the Belfer Center at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, whose research into those fateful “13 days in October” has brought much of the back-and-forth to light, “the lessons of the crisis for current policy have never been greater.”

In a Foreign Affairs article published last summer, he described the current confrontation between the U.S. and Iran as “a Cuban missile crisis in slow motion”.

Kennedy, he wrote, was given two options by his advisers: “attack or accept Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba.” But the president rejected both and instead was determined to forge a mutually acceptable compromise backed up by a threat to attack Cuba within 24 hours unless Krushchev accepted the deal.

Today, President Barack Obama is being faced with a similar binary choice, according to Allison: to acquiesce in Iran’s acquisition of a nuclear bomb or carry out a preventive air strike that, at best, could delay Iran’s nuclear programme by some years.

A “Kennedyesque third option,” he wrote, would be an agreement that verifiably constrains Iran’s nuclear programme in exchange for a pledge not to attack Iran so long as it complied with those constraints.

“I would hope that immediately after the election, the U.S. government will also turn intensely to the search for something that’s not very good – because it won’t be very good – but that is significantly better than attacking on the one hand or acquiescing on the other,” Allison told the Voice of America last week.

This very much appears to be what the Obama administration prefers, particularly in light of as-yet unconfirmed reports over the weekend that both Washington and Tehran have agreed in principle to direct bilateral talks, possibly within the framework of the P5+1 negotiations that also involve Britain, France, China, Russia and Germany, after the Nov. 6 election.

Allison also noted a parallel between the Cuban crisis and today’s stand-off between the U.S. and Iran – the existence of possible third-party spoilers.

Fifty years ago, Cuban Prime Minister Fidel Castro had favoured facing down the U.S. threat and even launching the missiles in the event of a U.S. attack.

But because the Cubans lacked direct control over the missiles, which were under Soviet command, they could be ignored. Moreover, Kennedy warned the Kremlin that it “would be held accountable for any attack against the United States emanating from Cuba, however it started,” according to Allison.

The fact that Israel, which has repeatedly threatened to attack Iran’s nuclear sites unilaterally, actually has the assets to act on those threats makes the situation today more complicated than that faced by Kennedy.

“Due to the secrecy surrounding the resolution of the Cuban missile crisis, the lesson that became ingrained in U.S. foreign policy-making was the importance of a show of force to make your opponent back down,” Kornbluh told IPS.

“But the real lesson is one of commitment to diplomacy, negotiation and compromise, and that was made possible by Kennedy’s determination to avoid a pre-emptive strike, which he knew would open a Pandora’s box in a nuclear age.”

]]>