by Hooshang Amirahmadi

President Barack Obama’s move towards normalization of relations with Cuba has generated lots of hope and analyses that a similar development may take place with Iran. Jim Lobe, founder of the Lobe Log and Washington Bureau Chief of the Inter Press Service, is one such observer. His recent article offers an excellent elaboration of the arguments. I rarely comment on writings by others, but his article deserves a response.

Lobe writes, “In my opinion, Obama’s willingness to make a bold foreign policy move [on Cuba] should—contrary to the narratives put out by the neoconservatives and other hawks—actually strengthen the Rouhani-Zarif faction within the Iran leadership who are no doubt arguing that Obama is serious both about reaching an agreement and forging a new relationship with the Islamic Republic.”

As someone who has spent 25 years trying to mend relations between the US and Iran, I wish Mr. Lobe and his liberal allies were right, and that their “neoconservative” opponents were wrong in their assessments that after Cuba comes Iran; unfortunately they are not. The truth is that Obama cannot so easily unlock the 35-year US-Iran entanglement that involves complex forces, including an Islamic Revolution.

First, Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif and President Hassan Rouhani used to tell Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei that Obama could be trusted, but after 14 months and many rounds of negotiations, they have now subscribed to Khamenei’s line that the US cannot be trusted. Iran’s nuclear program has already been reduced to a symbolic existence but the promised relief from key sanctions, Rouhani’s main incentive to negotiate, is nowhere on the horizon.

During the meeting in Oman between Kerry and Zarif just before the November 24, 2014 deadline for reaching a “comprehensive” deal, as disclosed by the parliamentarian Mohammad Nabavian in an interview, “[Secretary of State] Kerry crossed all Iranian red lines” and Zarif left for Tehran “thinking that the negotiations should stop.” One such red line concerns Iran’s missile program, which is now included in the negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program.

In a recent letter to his counterparts throughout the world regarding the talks and why a comprehensive deal was not struck last November, Zarif writes that “demands from the Western countries [i.e., the US] are humiliating and illegitimate” and that the “ball is now in their court.” Partly reflecting this disappointment, the Rouhani Government has increased Iran’s defense and intelligence budgets for 2015 by 33 percent and 48 percent respectively (the Iranian calendar begins on March 21).

Second, Zarif and Rouhani could not make the “beyond-the-NPT” concessions that they have made if the supreme leader had not authorized them. The argument that Khamenei and his “hardline” supporters are the obstacle misses the fact that while they have raised “concern” about Iran’s mostly unilateral concessions and the US’s “rapacious” demands, they (particularly the supreme leader) have consistently backed the negotiations and the Iranian negotiators.

Third, Lobe’s thinking suggests that the problem between the two governments is a discursive and personal one: if Khamenei is convinced that Obama is a honest man, then a nuclear agreement would be concluded and a new relationship would be forged between the two countries. What this genus of thinking misses is a radical “Islamic Revolution” and its “divine” Nizam (regime) that stands between Washington and Tehran.

The Islamic Revolution has been anti-American from its inception in 1979 (and not just in Iran), and will remain so as long as the first generation revolutionary leaders rule. The US has also been hostile to the theocratic regime and has often tried to change it. No wonder Khamenei and his people view the US as an “existential threat,” and to fend it off, they have built a “strategic depth” extending to Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Yemen and other countries.

Fourth, several times in the past the Iran watchers in the West have become excited about elections that have produced “moderate” governments, making them naively optimistic that a change in relations between the US and Iran would follow. What they miss is that the Islamic “regime” (nizam) and the Islamic “government” are two distinct entities, with the latter totally subordinated to the former.

Specifically, the Nizam (where the House of Leader and revolutionary institutions reside) is ideological and revolutionary, whereas the government has often been pragmatic. Indeed, in the last 35 years, the so-called hardliners have controlled the executive branch for less than 10 years. The division of labor should be easy to understand: the Nizam guards the divine Islamic Revolution against any deviation and intrusion while the government deals with earthly butter and bread matters.

Fifth, to avoid a losing military clash with the US and at the same time reduce Washington’s ability to change its regime or “liberalize” it, the Islamic Republic has charted a smart policy towards the US: “no-war, no-peace.” The US has also followed a similar policy towards Iran to calm both anti-war and anti-peace forces in the conflict. Thus, for over 35 years, US-Iran relations have frequently swung between heightened hostility and qualified moderation (in Khamenei’s words, “heroic flexibility”).

Sixth, the Cuban and Iranian cases are fundamentally dissimilar. True, the Castros were also anti-American and are first-generation leaders, but Fidel is retired and on his deathbed while his brother Raul has hardly been as revolutionary as Fidel. Besides, with regard to US-Cuban normalization, Fidel and his brother can claim more victory than Obama; after all, the Castros did not cave in, Obama did. Furthermore, the Castros are their own bosses, head a dying socialist regime, and are the judges of their own “legacy.”

In sharp contrast, Khamenei subscribes to a rising Islam, heads a living though conflicted theocracy, and subsists in the shadow of the late Ayatollah Khomeini who called the US a “wolf” and Iran a “sheep,” decreeing that they cannot coexist. Indeed, in the Cuban case, the US held the tough line while in the case of Iran, the refusal to reconcile is mutual. Furthermore, the Cuban lobby is a passing force and no longer a match for the world-wide support that the Cuban government garners. Conversely, in the Iranian case, Obama has to deal with powerful Israeli and Arab lobbies, and the Islamic Republic does not have effective international support.

On the other hand, we also have certain similarities between the Cuban and Iranian cases. For example, both revolutions have been subject to harsh US sanctions and other forms of coercion that Obama called a “failed approach.” Obama is also in his second term, free from the yoke of domestic politics, and wishes to build a lasting legacy. Despite these similarities, the differences between the Iranian Islamic regime and the Cuban socialist system make the former a tougher challenge for Obama to solve.

Finally, while I do not think that the Cuban course will be followed for Iran any time soon, I do think that certain developments are generating the imperative for an US-Iran reconciliation in the near future. On Iran’s side, they include a crippled economy facing declining oil prices, a young Iranian population demanding transformative changes, and the gradual shrinking of the first-generation Islamic revolutionary leaders.

On the US side, the changes include an imperial power increasingly reluctant to use force, rising Islamic extremism, growing instability in the Persian Gulf and the larger Middle East, and the difficulty of sustaining the “no-war, no-peace” status quo in the absence of a “comprehensive” deal on Iran’s nuclear program. However, on this last issue, in Washington and Tehran, pessimism now far outweighs optimism, a rather sad development. Let us hope that sanity will prevail.

Photo: Iranian President Hassan Rouhani greets a rally in commemoration of the Islamic Republic’s 35 anniversary of its 1979 revolution in Tehran, Iran on Feb. 11, 2014. Credit: ISNA/Hamid Forootan

]]>by Jasmin Ramsey

Another Israeli expert has contradicted Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s assessment of Iran’s nuclear program.

“The Iranian nuclear program will only be operational in another 10 years,” said Uzi Eilam, the former head of the Israel Atomic Energy Commission, during an interview with Ronen Bergman published today in the Israeli [...]]]>

by Jasmin Ramsey

Another Israeli expert has contradicted Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s assessment of Iran’s nuclear program.

“The Iranian nuclear program will only be operational in another 10 years,” said Uzi Eilam, the former head of the Israel Atomic Energy Commission, during an interview with Ronen Bergman published today in the Israeli daily, Ynet.

“The main issues are still ahead of us, but it is definitely possible to be optimistic. I think we should give the diplomatic process a serious chance, alongside ongoing sanctions,” said Eilam, who has held senior roles in the Israeli defense establishment.

“And I’m not even sure that Iran would want the bomb — it could be enough for them to be a nuclear threshold state — so that it could become a regional power and intimidate its neighbors,” he added.

Netanyahu has implored the international community to set a “red line” on Iran’s nuclear program, which he says is aimed at a nuclear weapon. The Israeli PM used a “cartoon bomb” prop to make this argument during his Sept. 27, 2012 UN General Assembly speech. Two weeks earlier, Netanyahu had said that Iran was 6-7 months from being 90% of the way to building a bomb during an interview with NBC’s “Meet the Press” program.

The next year, during his Oct. 1 2013 address to the UNGA, Netanyahu admitted that Iran had not crossed the line he had drawn on his diagram, but said Tehran was still positioning itself to be able to create a bomb and that this “vast and feverish effort has continued unabated” under Iranian President Hassan Rouhani.

Netanyahu has also called the interim deal on Iran’s nuclear program that was reached on Nov. 24, 2012 between Iran and the P5+1 (the U.S., Britain, France, China, and Russia plus Germany) a “historic mistake.”

The Israeli PM, who has been warning about an impending Iranian nuclear bomb for almost 20 years, has been relatively quiet during this year’s round of talks toward a comprehensive deal with Iran, which are set to resume on May 13 in Vienna Austria.

US officials have also detected a shift in Tel Aviv’s position toward a somewhat more reasonable stance, according to a report in Al-Monitor.

Several current and former Israeli defense and intelligence officials have cast doubt on Netanyahu’s statements on Iran’s nuclear program, which Tehran, a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, insists is peaceful.

“[Israel's leadership] presents a false view to the public on the Iranian bomb, as though acting against Iran would prevent a nuclear bomb. But attacking Iran will encourage them to develop a bomb all the faster,” said Israel’s former Internal Security Chief, Yuval Diskin, at an Israeli forum on Apr. 26, 2012.

“[Iran] is going step by step to the place where it will be able to decide whether to manufacture a nuclear bomb. It hasn’t decided to go the extra mile,” noted the head of the Israeli military, Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Benny Gantz, during an interview with Haaretz on Apr. 25, 2012.

“I don’t think [Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei] will want to go the extra mile. I think the Iranian leadership is composed of very rational people,” he said.

“[Attacking Iran is] the stupidest thing I have ever heard…It will be followed by a war with Iran,” said Meir Dagan, the former head of the Mossad, during a May 2011 Hebrew University conference.

“It is the kind of thing where we know how it starts, but not how it will end.” he added.

]]>via IPS News

In the wake of a renewed diplomatic push on the Iranian nuclear front, shared interests in Iran’s backyard could pave the way for Washington and Tehran to work toward overcoming decades of hostility.

“I think that if Iran and the United States are able to [...]]]>

via IPS News

In the wake of a renewed diplomatic push on the Iranian nuclear front, shared interests in Iran’s backyard could pave the way for Washington and Tehran to work toward overcoming decades of hostility.

“I think that if Iran and the United States are able to overcome their differences regarding Iran’s nuclear programme, if there begins to be some progress in that regard, then I do see opportunities for dialogue and cooperation on a broader range of issues, including my issues, which is to say Afghanistan,” Ambassador James F. Dobbins, the U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, told IPS at a briefing here Monday.

This summer’s election of Iran’s new president, Hassan Rouhani, a moderate cleric with centrist and reformist backing as well as close ties to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, has been followed by signals that Iran may be positioning itself to agree to a deal over its controversial nuclear programme.

Rouhani’s appointment of Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif to oversee Iran’s nuclear dossier has been received positively here by leading foreign policy elites who consider Zarif a worthy negotiating partner.

The Western-educated former Iranian ambassador to the United Nations is slotted to meet with his British counterpart William Hague at the U.N. General Assembly later this month, which could lead to a resumption of diplomatic ties that were halted following a 2011 storming of the British embassy in Tehran by a group of protestors.

Dobbins, who worked closely with Zarif in 2001 after being appointed by the George W. Bush administration to aid the establishment of a post-Taliban government in Afghanistan, told IPS that “Iran was quite helpful” with the task.

“I think it’s unfortunate that our cooperation, which was, I think, genuine and important back in 2001, wasn’t able to be sustained,” added Dobbins.

The U.S. halted official moves toward further cooperation with Iran following a 2002 speech by Bush that categorised Iran as part of an “axis of evil” with Iraq and North Korea.

While President Barack Obama’s “A New Beginning” speech in Cairo in 2009 indicated a move away from Bush-era rhetoric on the Middle East, the U.S.’s Iran policy has remained sanctions-centric – a main point of contention for Iran during last year’s nuclear talks.

Positive signs from both sides

But a recent string of events, which continued even as the U.S. seemed to be positioning itself to strike Iranian ally Syria, have led to speculation that the long-time adversaries may be edging toward direct talks, though the White House denied speculation that this could take place at the U.N. General Assembly.

Iran’s Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Marziyeh Afkham also verified the exchange but denied speculation that Syria was a subject.

“Obama’s letter was received, but it was not about Syria and it was a congratulation letter (to Iranian President Hassan Rouhani) whose response was sent,” Afkham told reporters in Tehran in comments posted on the semiofficial Fars News Agency.

That both leaders have publicly acknowledged such rare contact is an important development in and of itself, according to Robert E. Hunter, who served on the National Security Council staff throughout the Jimmy Carter administration.

“This is an effort as much as anything to test the waters in domestic American politics regarding direct talks, regarding the possibility of seeing whether something more productive can be done than in the past. And except out of Israel, I haven’t seen a lot of powerful protest,” Hunter told IPS.

“The Iranians have already backed off on the stuff about the Holocaust by saying it was that ‘other guy’. Now, and this is a reach, but keep in mind that as the slogan goes, the road between Tehran and Washington runs through Jerusalem,” said Hunter, who was U.S. ambassador to NATO (1993-98).

“A serious improvement of U.S.-Iran relations also requires Iran to do things in regard to Israel that will reduce Israel’s anxiety about Iranian intentions on the nuclear front, and on Hezbollah,” he said.

Hunter added that “compatible interests” between the two countries, including security and stability in Iraq and Afghanistan and freedom of shipping in the vital oil transport route, the Strait of Hormuz, could also pave the way to improved relations.

A shift in Iran

Even Khamenei, who has always been deeply suspicious of U.S. policy toward Iran, has given permission for Rouhani to enter into direct talks with the U.S., according to an op-ed published by Project Syndicate and written by former Iranian nuclear negotiator, Hossein Mousavian.

During a meeting Monday with Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), Khamenei also said he was “not opposed to correct diplomacy” and believes in “heroic flexibility”, according to an Al-Monitor translation.

Adding to the eyebrow-raising remarks was Khamenei’s echoing of earlier comments by Rouhani that the IRGC does not need to have a direct hand in politics.

“It is not necessary for it to act as a guard in the political scene, but it should know the political scene,” said Khamenei, who has nurtured years of close relations with the powerful branch of Iran’s military.

Iran sends out feelers

On Sept. 12, the head of Iran’s Atomic Energy Organisation Ali Akbar Salehi announced that Iran had reduced its stockpile of 20 percent low enriched uranium by converting it into fuel for the Tehran Research Reactor (TRR).

This was described as “misleading” by the Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS) based on how little LEU Iran had reportedly converted to fuel.

“As such, this action cannot be seen as a significant confidence building measure,” argued ISIS in a press release.

But Paul Pillar, a former top CIA analyst who served as the National Intelligence Officer for the Near East and South Asia (2000 to 2005), called this “an example of all-too-prevalent reductionism that seeks to fold political and psychological questions into technical ones.”

“Confidence-building measures can mean many things, but in general they have at least as much to do with perceptions and intentions as they do with gauging physical steps against some technical yardstick,” Pillar told IPS.

“Confidence-building measures…are gestures of goodwill and intent. They are not walls against a possible future ‘break-out’. If they were, they would not be confidence-building measures; they would be a solving of the whole problem,” he said.

Photo Credit: ISNA/Mehdi Ghasemi

]]>by Robert E. Hunter

Following the US-Russian agreement, the Syrian government’s chemical weapons must now be destroyed. To do this without putting UN employees at impossible risk, the Syrian civil war must also stop. To do that requires a plan by the Obama administration and others. To do that requires a realistic [...]]]>

by Robert E. Hunter

Following the US-Russian agreement, the Syrian government’s chemical weapons must now be destroyed. To do this without putting UN employees at impossible risk, the Syrian civil war must also stop. To do that requires a plan by the Obama administration and others. To do that requires a realistic goal — not just “victory” for the rebels — but which ones?

At best, last week’s diplomacy puts the Obama administration back at Square One before the major chemical weapons attacks on August 21. Still, there are differences. Firstly, the threat of force, strongly put forth by the president in his dramatic speech to the nation last Tuesday, is in fact off the table. For this to be otherwise would require some triggering mechanism of Syrian government “non-compliance,” and Russia would have to concur. It would also return President Obama to the dilemma of trying to get Congressional and public approval for US military force. Two non-starters.

In fact, the debate on the use of force is mostly about US domestic politics. The president should draw upon the famous quotation misattributed to Vermont Senator George Aiken during the Vietnam War: “Declare victory and get out.”

Secondly, the US can no longer ignore what has been happening in Syria and must ramp up its diplomatic efforts.

Thirdly, Russia is now directly involved in Middle East diplomacy. Getting it to “butt out” now is also a non-starter. Maybe President Vladimir Putin will see advantages in genuinely working toward a broader settlement in Syria and elsewhere in the region. The price: Russia will henceforth be “in” and will have to be recognized as more than just a successor to the country whipped in the Cold War.

Both Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan knew how to change bad news to good in foreign policy: the former by “going to China” and making possible withdrawal from Vietnam; the latter by proposing to Mikhail Gorbachev at Reykjavik that the US and USSR get rid of all nuclear weapons, an ice-breaker that helped end the Cold War.

For Obama, “changing the subject” in Syria and the broader Middle East should include the following components:

- Stop insisting that the possible use of force against Syria “remains on the table.” It has no further value and just keeps alive the debate over US “credibility.”

- Recognize that the Syrian government will not negotiate when the outcome is predetermined (the departure of President Bashar al-Assad). If President Obama can’t for domestic political reasons back off from this second “red line,” at least the Alawite community needs cast-iron assurances that it will not be butchered following a deal and can continue to play a major political role.

- Pursue a peace process relentlessly as an honest broker, with all other interested outside countries, co-chaired with Russia and under UN auspices.

- Tell US Arab allies whose citizens export Islamist fundamentalism or fund weapons for terrorists in Syria and elsewhere to “cut it out.”

- Help restrain the wider Sunni-Shia civil war in the region, in part through demonstrating that the US will remain strategically engaged, while acting as an honest broker.

- Take advantage of Iran’s new presidency to propose direct US-Iranian talks and pursue a nuclear agenda that has a serious chance of success, as opposed to past US demands that Iran give us what we want as a precondition. Recognize publicly that we respect Iran’s legitimate security interests, as we rightly demand that Tehran reciprocate.

- Explore possible compatible interests with Iran in Afghanistan, Iraq, freedom of shipping through the Strait of Hormuz, an Incidents at Sea Agreement (as the US and Soviet Union did in 1972) – and perhaps even over Syria.

- Engage the Europeans more fully in both political and economic developments in the Middle East and North Africa, as part of a new Transatlantic Bargain.

- Start shifting the US focus in the region from military to political and economic tools of power and influence. Put substance behind the spirit of Obama’s 2009 Cairo speech that did so much for US standing with the region’s people.

- Propose a long-term security framework for the Middle East, in which all countries can take part; all will oppose terrorism (including its inspiration), all will respect the legitimate security interests of its neighbors, and all will search for confidence-building measures.

- Engage all interested states (including Iran, Russia, China, Pakistan, and India) in developing a framework for Afghanistan after 2014.

- Recognize that Israeli-Palestinian negotiations can only succeed when Israel’s security concerns (Egypt, Syria, and Iran) are addressed and the blockade of Gaza ends.

Other steps may be needed, but all elements in the Middle East must be considered together. The US must exercise leadership. It must primarily work for regional security, political and economic development, be the security provider of last resort, honor its commitments, act as an honest broker, and prove itself worthy of trust.

]]>It’s too early to tell yet whether Russia’s initiative has removed the threat of a U.S. strike on Syria over the alleged use of chemical weapons. While the signs are as good as could be hoped for at this point, a lot can happen in the upcoming weeks. And, whatever the final [...]]]>

It’s too early to tell yet whether Russia’s initiative has removed the threat of a U.S. strike on Syria over the alleged use of chemical weapons. While the signs are as good as could be hoped for at this point, a lot can happen in the upcoming weeks. And, whatever the final disposition of a U.S. strike on Syria, the plight of the Syrian people, which has played almost no substantive part in this debate and has largely been reduced to a propaganda tool for whomever is making their case today, isn’t going to be affected much one way or the other.

But we have already seen enough to determine some winners and losers in this political drama:

AIPAC: Loser The major pro-Israel lobbying organization made a serious mistake by taking their advocacy for a strike on Syria to such a public forum. It would have been easy enough for them to quietly bring their lobbyists to the Hill and advocate their position. The decision to do so as loudly as they did is puzzling to say the least. It seems pretty clear that the Obama administration actually recruited AIPAC to try to drum up support for their position. The extremely powerful lobbying group had followed Israel’s lead and stayed generally silent on Syria until Obama’s announcement of a strike, then suddenly dove in with both feet.

It didn’t work. Based on reports, it seems clear that the lobbyists were less than enthusiastic and their efforts didn’t sway lawmakers. AIPAC’s attempts to keep Israel out of it also failed. They were scrupulous about not mentioning Israel’s security in their talking points, but the very presence of a lobbying group whose raison d’être is protecting Israel’s interests overwhelmed that attempt. AIPAC thought it could separate itself, in the public eye and on this one issue, from Israel, but that was a fool’s game. It doesn’t help that it was untrue that this was not about Israel. While Israel would surely prefer that Syria not have any chemical or biological weapons, whatever the outcome of the civil war, it’s not that high a priority for them.

But Iran is. Part of the case for a Syria strike has been the notion that backing off would show weakness and embolden Iran in its alleged quest for nuclear weapons. Israel, therefore, backed Obama’s decision, but this wasn’t a compelling reason for it to get publicly involved in the domestic quarrel over the strike. Indeed, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was said to have made a few phone calls to allies on the Hill, but it was clear from the outset that he had learned well the lessons from the 2012 election about being seen as meddling too much in domestic US politics. He cannot be happy with AIPAC’s strategy here of doing this so loudly and publicly.

Between the bad strategy and the ineffectiveness of their lobbying, at least for now, AIPAC takes a hit here. It’s by no means a crippling one, but it is significant. When the issue can be framed in terms of Israeli security, there is little doubt AIPAC will have as much sway as always, and when the issue is not one that the U.S. public feels strongly about, their ability to move campaign contributions will have the same impact it has had before. But every time AIPAC is seen to be advocating policy for the U.S. based on Israeli interests, the lobby takes a hit. Enough of those over time will erode its dominance.

John Kerry: loser If Kerry was still an elected official, this might be a different score. But he is a diplomat now and his standing on the world stage was clearly diminished by his actions in this drama. He gets the benefit of it being better to be lucky than good, as his now-famous gaffe ended up being exactly the plan Russia put forth for averting a U.S. strike. But few, aside from fawning Obama boosters, are buying that this was a plan. If it were, the State Department wouldn’t have immediately walked back the statement; it would have waited to see if Russia would “take the bait.” Kerry has come off in all of this as looking all too similar to his predecessors in the Bush administration, talking of conclusive proof while U.S. military and intelligence officials said that his evidence was far from a “slam-dunk.” Kerry is now trumpeting the upcoming UN report that is expected to conclusively state that chemical weapons were used. But everyone, with the exception of a marginal few, believes that already. The question is whether the Assad regime carried out the attack under Assad’s authority. That is far less clear, and the UN does not appear to be stating that conclusion. The evidence thus far suggests that, while Assad having ordered the chemical attack remains a distinct possibility, it is at least as possible that the attack was perpetrated by a rogue commander who had access to the weapons, and against Assad’s wishes.

In any case, Kerry’s eagerness for this attack, and his disregard for international law and process, contrasts starkly with the Obama administration’s stated preference to act differently from its predecessor. Kerry’s standing in the U.S. can easily recover from this, but in the international arena, which is where he works, it is going to be much tougher.

Barack Obama: loser Obama has been in a tough position regarding Syria. He surely does not want to get involved there; such action stands in stark contrast to his desired “pivot to Asia,” as well as his promise to “end wars, not to start them.” And he is as aware as anyone else that the U.S. has little national security interest in Syria. Moreover, despite his opposition to Assad, the U.S. is less than enamored over the prospects of a Syria after Assad, which is likely to be the scene of further battles for supremacy that are very likely to lead to regimes we are not any more in sync with than we are with Assad, quite possibly a good deal less.

But his “red line” boxed him in. It was his credibility, more than the United States’ that was at stake here, and it takes a hit. While it is highly unlikely that anyone in Tehran is changing their view of the U.S. and their own strategic position because of this, it is true that this will shake the confidence of Israel, Saudi Arabia, the al-Sisi government in Egypt and other U.S. allies in the region. That might be good in the long run, but in the short term, it will harm Obama’s maneuverability in the region.

Domestically, Obama reinforced his image as a weak and indecisive leader on foreign policy; his appeal to Congress pleased some of his supporters, but few others were impressed. He has been blundering around the Middle East for five years now, and he doesn’t seem to be getting any better at it, which is discouraging, to say the least.

Vladimir Putin: winner Putin comes out of this in a great position. He really doesn’t care if Assad stays or goes as long as Syria (or what’s left of it) remains in the Russian camp. Acting to forestall or possibly even prevent a U.S. strike on another Arab country will score him points in the region, although after Russia’s actions in Chechnya, he’ll never be terribly popular in the Muslim world. Still, capitalizing on the even deeper mistrust of the United States can get him a long way, and this episode is going to help a lot in the long run. More immediately, it helps Putin set up a diplomatic process that includes elements of the Assad regime, something he has been after for a long time but the rebels have staunchly opposed. With the U.S. now on the diplomatic defensive, he might be able to get it done, especially as war-weariness in Syria grows.

Israel: winner Israel has stayed out of the debate to a large degree. Their rebuke of AIPAC and their public silence on the U.S. debate has helped erase the memory of Netanyahu’s clumsy interference on behalf of his friend, Mitt Romney a year ago. Israel is in no hurry to see the civil war in Syria end, as the outcome is unlikely to be in its favor whichever side wins. And, while all eyes are on Syria no one is paying attention to Palestinian complaints about the failing peace talks. That makes it even easier for Israel to comply with U.S. wishes and keep silent about the talks, planting seeds for blaming the Palestinians for the talks’ inevitable failure. Unlike Obama, Netanyahu seems to be learning from his mistakes, which is not a pleasant prospect for the Palestinians.

Iran: winner While it’s true that the Syria controversy will have little impact on the U.S.-Iran standoff, the show of intense reluctance to stretch the U.S. military arm out again can’t help but please Tehran. It doesn’t hurt either that when, a few days ago, the U.S. tried to appease Israel by mumbling about some “troublesome” things regarding the Iranian nuclear problem, no one took it very seriously and hopes remain high that President Hassan Rouhani will change the course of the standoff. Russia’s maneuvers to keep Syria within its sphere of influence bode well for Iran as well.

The Syrian people: slight winners A U.S. strike would have almost certainly caused an escalation in the Assad regime’s conventional warfare in Syria. Ninety-nine percent of the deaths and refugees have been caused by conventional weapons — that was a good reason for the U.S. not to do it. But increased momentum behind the Russian push is also likely to ensure the war goes on for some time and this increases chances that remnants of the current regime will remain in place at the end of it, even if Assad himself is ousted. Now that the U.S. is determined to arm the rebels to a greater degree, an increasing war of attrition is more likely and that bodes very ill for the people caught in the middle. Considering that some one-third of the population is now either internally displaced or seeking refuge in other countries and a death toll of over 110,000, one must consider avoiding an escalation a victory for these beleaguered people. But outside intervention to stop the killing seems as remote as ever, and the hopes for an international conference to try to settle the conflict are advanced by this episode a bit, but are still uncertain at best.

-Photo: U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry directs a comment to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu after a meeting that touched on Middle East peace talks and Syrian chemical weapons, in Jerusalem on September 15, 2013. Credit: State Department

]]>via USIP

Iran has mixed feelings and conflicting interests in the Syrian crisis. Tehran has a strategic interest in opposing chemical weapons due to its own horrific experience during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. For years, President Saddam Hussein’s military used chemical weapons that killed thousands of Iranian soldiers. So [...]]]>

via USIP

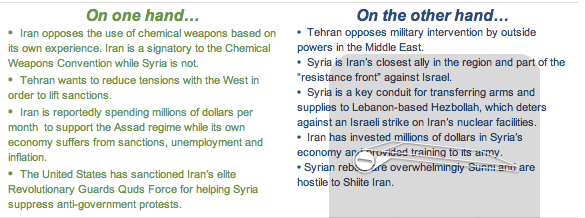

Iran has mixed feelings and conflicting interests in the Syrian crisis. Tehran has a strategic interest in opposing chemical weapons due to its own horrific experience during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. For years, President Saddam Hussein’s military used chemical weapons that killed thousands of Iranian soldiers. So Iran actually shares interests with the United States, European nations and the Arab League in opposing any use of chemical weapons.

But the Islamic Republic also has compelling reasons to continue supporting Damascus. The Syrian regime is Iran’s closest ally in the Middle East and the geographic link to its Hezbollah partners in Lebanon. As a result, Tehran vehemently opposes U.S. intervention or any action that might change the military balance against President Bashar Assad.

The Iran-Syria alliance is more than a marriage of convenience. Tehran and Damascus have common geopolitical, security, and economic interests. Syria was one of only two Arab nations (the other being Libya) to support Iran’s fight against Saddam Hussein, and it was an important conduit for weapons to an isolated Iran. Furthermore, Hafez Assad, Bashar’s father, allowed Iran to help create Hezbollah, the Shiite political movement in Lebanon. Its militia, trained by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, has been an effective tool against Syria’s archenemy, Israel.

Relations between Tehran and Damascus have been rocky at times. Hafez Assad clashed with Hezbollah in Lebanon and was wary of too much Iranian involvement in his neighborhood. But his death in 2000 reinvigorated the Iran-Syria alliance. Bashar Assad has been much more enthusiastic about Iranian support, especially since Hezbollah’s “victorious” 2006 conflict with Israel.

In the last decade, Iran’s Revolutionary Guards have trained, equipped, and at times even directed Syria’s security and military forces. Hundreds of thousands of Iranian pilgrims and tourists visited Syria before its civil war, and Iranian companies made significant investments in the Syrian economy.

Fundamentalist figures within the Guards view Syria as the “front line” of Iranian resistance against Israel and the United States. Without Syria, Iran would not be able to supply Hezbollah effectively, limiting its ability to help its ally in the event of a war with Israel. Hezbollah wields thousands of rockets able to strike Israel, providing Iran deterrence against Israel — especially if Tel Aviv chose to strike Iran’s nuclear facilities. A weakened Hezbollah would directly impact Iran’s national security. Syria’s loss could also tip the balance in Iran’s rivalry with Saudi Arabia, making the Wahhabi kingdom one of the most influential powers in the Middle East.

In the run up to a U.S. decision on military action against Syria, Iranian leaders appeared divided.

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and hardline lawmakers reacted with alarm to possible U.S. strikes against the Assad regime. And Revolutionary Guards commanders threatened to retaliate against U.S. interests. The hardliners clearly viewed the Assad regime as an asset worth defending as of September 2013.

But President Hassan Rouhani, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif and former President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani adopted a more critical line on Syria. “We believe that the government in Syria has made grave mistakes that have, unfortunately, paved the way for the situation in the country to be abused,” Zarif told a local publication in September 2013.

Rafsanjani, still an influential political figure, reportedly said that the Syrian government gassed its own people. This was a clear breach of official Iranian policy, which has blamed the predominantly Sunni rebels. Rafsanjani’s words suggested that he viewed unconditional support for Assad as a losing strategy. His remark also earned a rebuke from Khamenei, who warned Iranian officials against crossing the “principles and red lines” of the Islamic Republic. Khamenei’s message may have been intended for Rouhani’s government, which is closely aligned with Rafsanjani and seems to increasingly view the Syrian regime as a liability.

Regardless, a significant section of Iran’s political elite could be amenable to engaging the United States on Syria. Both sides have a common interest: preventing Sunni extremists from coming to power in Damascus. Iran and the United States also prefer a negotiated settlement over military intervention to solve the crisis. Tehran might need to be included in a settlement given its influence in Syria. Negotiating with Iran on Syria could ultimately help America’s greater goal of a diplomatic breakthrough, not only on Syria but Tehran’s nuclear program as well.

– Alireza Nader is a senior international policy analyst at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation.

*Read Alireza Nader’s chapter on the Revolutionary Guards in “The Iran Primer”

Photo Credits: Bashar Assad and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei via Leader.ir, Syria graphic via Khamenei.ir Facebook

]]>by Andrew J. Bacevich

via Tom Dispatch

Sometimes history happens at the moment when no one is looking. On weekends in late August, the president of the United States ought to be playing golf or loafing at Camp David, not making headlines. Yet Barack Obama chose Labor Day weekend [...]]]>

by Andrew J. Bacevich

via Tom Dispatch

Sometimes history happens at the moment when no one is looking. On weekends in late August, the president of the United States ought to be playing golf or loafing at Camp David, not making headlines. Yet Barack Obama chose Labor Day weekend to unveil arguably the most consequential foreign policy shift of his presidency.

In an announcement that surprised virtually everyone, the president told his countrymen and the world that he was putting on hold the much anticipated U.S. attack against Syria. Obama hadn’t, he assured us, changed his mind about the need and justification for punishing the Syrian government for its probable use of chemical weapons against its own citizens. In fact, only days before administration officials had been claiming that, if necessary, the U.S. would “go it alone” in punishing Bashar al-Assad’s regime for its bad behavior. Now, however, Obama announced that, as the chief executive of “the world’s oldest constitutional democracy,” he had decided to seek Congressional authorization before proceeding.

Obama thereby brought to a screeching halt a process extending back over six decades in which successive inhabitants of the Oval Office had arrogated to themselves (or had thrust upon them) ever wider prerogatives in deciding when and against whom the United States should wage war. Here was one point on which every president from Harry Truman to George W. Bush had agreed: on matters related to national security, the authority of the commander-in-chief has no fixed limits. When it comes to keeping the country safe and securing its vital interests, presidents can do pretty much whatever they see fit.

Here, by no means incidentally, lies the ultimate the source of the stature and prestige that defines the imperial presidency and thereby shapes (or distorts) the American political system. Sure, the quarters at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue are classy, but what really endowed the postwar war presidency with its singular aura were the missiles, bombers, and carrier battle groups that responded to the commands of one man alone. What’s the bully pulpit in comparison to having the 82nd Airborne and SEAL Team Six at your beck and call?

Now, in effect, Obama was saying to Congress: I’m keen to launch a war of choice. But first I want you guys to okay it. In politics, where voluntarily forfeiting power is an unnatural act, Obama’s invitation qualifies as beyond unusual. Whatever the calculations behind his move, its effect rates somewhere between unprecedented and positively bizarre — the heir to imperial prerogatives acting, well, decidedly unimperial.

Obama is a constitutional lawyer, of course, and it’s pleasant to imagine that he acted out of due regard for what Article 1, Section 8, of that document plainly states, namely that “the Congress shall have power… to declare war.” Take his explanation at face value and the president’s decision ought to earn plaudits from strict constructionists across the land. The Federalist Society should offer Obama an honorary lifetime membership.

Of course, seasoned political observers, understandably steeped in cynicism,dismissed the president’s professed rationale out of hand and immediately began speculating about his actual motivation. The most popular explanation was this: having painted himself into a corner, Obama was trying to lure members of the legislative branch into joining him there. Rather than a belated conversion experience, the president’s literal reading of the Constitution actually amounted to a sneaky political ruse.

After all, the president had gotten himself into a pickle by declaring back in August 2012 that any use of chemical weapons by the government of Bashar al-Assad would cross a supposedly game-changing “red line.” When the Syrians (apparently) called his bluff, Obama found himself facing uniformly unattractive military options that ranged from the patently risky — joining forces with the militants intent on toppling Assad — to the patently pointless — firing a “shot across the bow” of the Syrian ship of state.

Meanwhile, the broader American public, awakening from its summertime snooze, was demonstrating remarkably little enthusiasm for yet another armed intervention in the Middle East. Making matters worse still, U.S. military leaders and many members of Congress, Republican and Democratic alike, were expressing serious reservations or actual opposition. Press reports evencited leaks by unnamed officials who characterized the intelligence linking Assad to the chemical attacks as no “slam dunk,” a painful reminder of how bogus information had paved the way for the disastrous and unnecessary Iraq War. For the White House, even a hint that Obama in 2013 might be replaying the Bush scenario of 2003 was anathema.

The president also discovered that recruiting allies to join him in this venture was proving a hard sell. It wasn’t just the Arab League’s refusal to give an administration strike against Syria its seal of approval, although that was bad enough. Jordan’s King Abdullah, America’s “closest ally in the Arab world,”publicly announced that he favored talking to Syria rather than bombing it. As for Iraq, that previous beneficiary of American liberation, its government wasrefusing even to allow U.S. forces access to its airspace. Ingrates!

For Obama, the last straw may have come when America’s most reliable (not to say subservient) European partner refused to enlist in yet another crusade to advance the cause of peace, freedom, and human rights in the Middle East. With memories of Tony and George W. apparently eclipsing those of Winston and Franklin, the British Parliament rejected Prime Minister David Cameron’s attempt to position the United Kingdom alongside the United States. Parliament’s vote dashed Obama’s hopes of forging a coalition of two and so investing a war of choice against Syria with at least a modicum of legitimacy.

When it comes to actual military action, only France still entertains the possibility of making common cause with the United States. Yet the number of Americans taking assurance from this prospect approximates the number who know that Bernard-Henri Lévy isn’t a celebrity chef.

John F. Kennedy once remarked that defeat is an orphan. Here was a war bereft of parents even before it had begun.

Whether or Not to Approve the War for the Greater Middle East

Still, whether high-minded constitutional considerations or diabolically clever political machinations motivated the president may matter less than what happens next. Obama lobbed the ball into Congress’s end of the court. What remains to be seen is how the House and the Senate, just now coming back into session, will respond.

At least two possibilities exist, one with implications that could prove profound and the second holding the promise of being vastly entertaining.

On the one hand, Obama has implicitly opened the door for a Great Debate regarding the trajectory of U.S. policy in the Middle East. Although a week or ten days from now the Senate and House of Representatives will likely be voting to approve or reject some version of an Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF), at stake is much more than the question of what to do about Syria. The real issue — Americans should hope that the forthcoming congressional debate makes this explicit — concerns the advisability of continuing to rely on military might as the preferred means of advancing U.S. interests in this part of the world.

Appreciating the actual stakes requires putting the present crisis in a broader context. Herewith an abbreviated history lesson.

Back in 1980, President Jimmy Carter announced that the United States would employ any means necessary to prevent a hostile power from gaining control of the Persian Gulf. In retrospect, it’s clear enough that the promulgation of the so-called Carter Doctrine amounted to a de facto presidential “declaration” of war (even if Carter himself did not consciously intend to commit the United States to perpetual armed conflict in the region). Certainly, what followed was a never-ending sequence of wars and war-like episodes. Although the Congress never formally endorsed Carter’s declaration, it tacitly acceded to all that his commitment subsequently entailed.

Relatively modest in its initial formulation, the Carter Doctrine quickly metastasized. Geographically, it grew far beyond the bounds of the Persian Gulf, eventually encompassing virtually all of the Islamic world. Washington’s own ambitions in the region also soared. Rather than merely preventing a hostile power from achieving dominance in the Gulf, the United States was soon seeking to achieve dominance itself. Dominance — that is, shaping the course of events to Washington’s liking — was said to hold the key to maintaining stability, ensuring access to the world’s most important energy reserves, checking the spread of Islamic radicalism, combating terrorism, fostering Israel’s security, and promoting American values. Through the adroit use of military might, dominance actually seemed plausible. (So at least Washington persuaded itself.)

Relatively modest in its initial formulation, the Carter Doctrine quickly metastasized. Geographically, it grew far beyond the bounds of the Persian Gulf, eventually encompassing virtually all of the Islamic world. Washington’s own ambitions in the region also soared. Rather than merely preventing a hostile power from achieving dominance in the Gulf, the United States was soon seeking to achieve dominance itself. Dominance — that is, shaping the course of events to Washington’s liking — was said to hold the key to maintaining stability, ensuring access to the world’s most important energy reserves, checking the spread of Islamic radicalism, combating terrorism, fostering Israel’s security, and promoting American values. Through the adroit use of military might, dominance actually seemed plausible. (So at least Washington persuaded itself.)

What this meant in practice was the wholesale militarization of U.S. policy toward the Greater Middle East in a period in which Washington’s infatuation with military power was reaching its zenith. As the Cold War wound down, the national security apparatus shifted its focus from defending Germany’s Fulda Gap to projecting military power throughout the Islamic world. In practical terms, this shift found expression in the creation of Central Command (CENTCOM), reconfigured forces, and an eternal round of contingency planning, war plans, and military exercises in the region. To lay the basis for the actual commitment of troops, the Pentagon established military bases, stockpiled material in forward locations, and negotiated transit rights. It also courted and armed proxies. In essence, the Carter Doctrine provided the Pentagon (along with various U.S. intelligence agencies) with a rationale for honing and then exercising new capabilities.

Capabilities expanded the range of policy options. Options offered opportunities to “do something” in response to crisis. From the Reagan era on, policymakers seized upon those opportunities with alacrity. A seemingly endless series of episodes and incidents ensued, as U.S. forces, covert operatives, or proxies engaged in hostile actions (often on multiple occasions) in Lebanon, Libya, Iran, Somalia, Bosnia, Kosovo, Saudi Arabia, the Sudan, Yemen, Pakistan, the southern Philippines, and in the Persian Gulf itself, not to mention Iraq and Afghanistan. Consider them altogether and what you have is a War for the Greater Middle East, pursued by the United States for over three decades now. If Congress gives President Obama the green light, Syria will become the latest front in this ongoing enterprise.

Profiles in Courage? If Only

A debate over the Syrian AUMF should encourage members of Congress — if they’ve got the guts — to survey this entire record of U.S. military activities in the Greater Middle East going back to 1980. To do so means almost unavoidably confronting this simple question: How are we doing? To state the matter directly, all these years later, given all the ordnance expended, all the toing-and-froing of U.S. forces, and all the lives lost or shattered along the way, is mission accomplishment anywhere insight? Or have U.S. troops — the objects of such putative love and admiration on the part of the American people — been engaged over the past 30-plus years in a fool’s errand? How members cast their votes on the Syrian AUMF will signal their answer — and by extension the nation’s answer — to that question.

To okay an attack on Syria will, in effect, reaffirm the Carter Doctrine and put a stamp of congressional approval on the policies that got us where we are today. A majority vote in favor of the Syrian AUMF will sustain and probably deepen Washington’s insistence that the resort to violence represents the best way to advance U.S. interests in the Islamic world. From this perspective, all we need to do is try harder and eventually we’ll achieve a favorable outcome. With Syria presumably the elusive but never quite attained turning point, the Greater Middle East will stabilize. Democracy will flourish. And the United States will bask in the appreciation of those we have freed from tyranny.

To vote against the AUMF, on the other hand, will draw a red line of much greater significance than the one that President Obama himself so casually laid down. Should the majority in either House reject the Syrian AUMF, the vote will call into question the continued viability of the Carter Doctrine and all that followed in its wake.

It will create space to ask whether having another go is likely to produce an outcome any different from what the United States has achieved in the myriad places throughout the Greater Middle East where U.S. forces (or covert operatives) have, whatever their intentions, spent the past several decades wreaking havoc and sowing chaos under the guise of doing good. Instead of offering more of the same – does anyone seriously think that ousting Assad will transform Syria into an Arab Switzerland? — rejecting the AUMF might even invite the possibility of charting an altogether different course, entailing perhaps a lower military profile and greater self-restraint.

What a stirring prospect! Imagine members of Congress setting aside partisan concerns to debate first-order questions of policy. Imagine them putting the interests of the country in front of their own worries about winning reelection or pursuing their political ambitions. It would be like Lincoln vs. Douglas or Woodrow Wilson vs. Henry Cabot Lodge. Call Doris Kearns Goodwin. Call Spielberg or Sorkin. Get me Capra, for God’s sake. We’re talking high drama of blockbuster proportions.

On the other hand, given the record of the recent past, we should hardly discount the possibility that our legislative representatives will not rise to the occasion. Invited by President Obama to share in the responsibility for deciding whether and where to commit acts of war, one or both Houses — not known these days for displaying either courage or responsibility — may choose instead to punt.

As we have learned by now, the possible ways for Congress to shirk its duty are legion. In this instance, all are likely to begin with the common supposition that nothing’s at stake here except responding to Assad’s alleged misdeeds. To refuse to place the Syrian crisis in any larger context is, of course, a dodge. Yet that dodge creates multiple opportunities for our elected representatives to let themselves off the hook.

Congress could, for example, pass a narrowly drawn resolution authorizing Obama to fire his “shot across the bow” and no more. In other words, it could basically endorse the president’s inclination to substitute gesture for policy.

Or it could approve a broadly drawn, but vacuous resolution, handing the president a blank check. Ample precedent exists for that approach, since it more or less describes what Congress did in 1964 with the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, opening the way to presidential escalation in Vietnam, or with theAUMF it passed in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, giving George W. Bush’s administration permission to do more or less anything it wanted to just about anyone.

Even more irresponsibly, Congress could simply reject any Syrian AUMF, however worded, without identifying a plausible alternative to war, in effect washing its hands of the matter and creating a policy vacuum.

Will members of the Senate and the House grasp the opportunity to undertake an urgently needed reassessment of America’s War for the Greater Middle East? Or wriggling and squirming, will they inelegantly sidestep the issue, opting for short-term expediency in place of serious governance? In an age where the numbing blather of McCain, McConnell, and Reid have replaced the oratory of Clay, Calhoun, and Webster, merely to pose the question is to answer it.

But let us not overlook the entertainment value of such an outcome, which could well be formidable. In all likelihood, high comedy Washington-style lurks just around the corner. So renew that subscription to The Onion. Keep an eye on Doonesbury. Set the TiVo to record Jon Stewart. This is going to be really funny — and utterly pathetic. Where’s H.L. Mencken when we need him?

Andrew J. Bacevich is a professor of history and international relations at Boston University. He is the author of the new book, Breach of Trust: How Americans Failed Their Soldiers and Their Country (Metropolitan Books).

Copyright 2013 Andrew Bacevich

]]>“…my credibility is not on the line. The international community’s credibility is on the line.”

– President Barack Obama, Stockholm, September 4, 2013

President Obama and other US supporters of attacking Syria in response to its alleged use of chemical weapons have based much of their argument on the issue [...]]]>

“…my credibility is not on the line. The international community’s credibility is on the line.”

– President Barack Obama, Stockholm, September 4, 2013

President Obama and other US supporters of attacking Syria in response to its alleged use of chemical weapons have based much of their argument on the issue of credibility. In particular, will other nations (and non-national elements, like terrorist groups) take seriously US declarations if we do not now follow through on preserving Obama’s “red line?”

This question relates to one of the most important elements of statecraft, especially for the United States, which presents itself as the “indispensable nation” and is seen by many others to be so. Further, if the US does not take the lead in trying to reestablish the prohibition on chemical weapons, no one else will do so.

More generally, if the US were seen as being haphazard or even indifferent to the commitments it makes, especially regarding the use of force in specified circumstances, bad results could ensue. Enemies could seek to exploit what they would perceive as American weakness; allies and partners could be less certain that the US would come to their assistance when they were threatened in some way.

This was the conundrum that bedeviled every US administration during the Cold War, as it sought to reassure European allies that the US, even at the price of its own destruction, would use nuclear weapons if the Soviet Union was not, through such US commitment, deterred from aggression against the West.

At this point, with Syria’s violating Mr. Obama’s red line on the use of chemical weapons, reinforced by his declaration last weekend that he will use force, he has no choice but to do so. That will be true even if Congress votes down the authorization he has sought (which it is unlikely to do) and even if he now goes to the United Nations for a mandate to act (which UN Security Council permanent members Russia and China would veto). Obama has “nailed his colors to the mast,” and failing to follow through, it is argued, would have consequences. Contrary to his recent statement in Stockholm, his credibility as president and commander-in-chief is, indeed, “on the line,” certainly in Washington’s unforgiving politics.

But what are those “consequences?” Are all red lines equally significant? Does failure to honor every declared commitment, formal or informal, large or small, always mean that other US commitments will not be taken seriously? It is hard to accept that proposition at face value — and countries which have tested it have rued the day. Indeed, like beauty, credibility is very much “in the eye of the beholder.”

Certainly, some commitments are more important than others. It would not matter if the president promised to quit smoking and did not; but it would matter very much if he pledged to defend the nation against a terrorist attack and sat idly by in face of another 9/11. “Credibility” must thus be seen on a sliding scale, and deciding where on this scale a particular commitment lies is a matter of judgment. (It is also important not to declare a “red line” if it does not truly relate to US national security interests, as Obama did in the current instance.) This is a major reason that most US security commitments take the form of treaties, ratified by the Senate.

The first requirement is to match the commitment to an objective reality of US security needs, as clearly understood both by the US and others. While deterring the use of chemical weapons is desirable and has a long history stemming in particular from World War I, what has happened in Syria does not directly impact on the security of the United States (chemical weapons have also accounted for less than two percent of casualties in the Syrian civil war, to which the “international community” has been largely indifferent). It is not like the attack on Pearl Harbor or 9/11. It is not like Saddam Hussein’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait, which put at risk a large fraction of the world’s exportable hydrocarbons. Had the United States not responded with military force to these direct threats, allies could rightly have wondered about American willpower, and enemies could have tested it elsewhere. Not only would US security have been put in jeopardy, so would the confidence that others have reposed in us. That is not now the case in Syria. Nor, despite the president’s assertion, is this a matter of the international community’s credibility, an effort to spread the responsibility and show the American people that the US is just the agent of a broad consensus. The risk in making that assertion is that a large fraction of the world’s nations do not agree that attacking Syria will help, and that list goes far beyond Russia, China and Iran.

President Obama has made attacking Syria a matter of US credibility. But that can arguably also be less a matter of objective reality, based on cool analysis, than the need to build congressional and popular support for a decision already taken. He can thus raise the stakes to try building political support for a decision he has already made. He knows there is little or no risk of US casualties, given the reliance on stand-off weapons, as was done most recently in the Libya conflict. Given that fact, what objection can there be to making a demonstration of military force, which might encourage “the others” to think twice about using chemical weapons?

The problem lies not in trying to fence off this particularly odious weapon, but in what happens after the US punishes Syria. It is one thing to argue that American credibility is at stake, it is quite another to ignore what has to be a key requirement in establishing that credibility, as well as demonstrating US leadership: laying out a convincing strategy for the Day After. The idea that a limited use of force can teach the Assad regime a lesson without escalating the conflict even further and tipping the balance in favor of the rebels assumes precision in the use of military force that has few if any historical precedents.

And if Assad were toppled, what then? The Syrian civil war pits the Alawite minority rulers against the majority of the population. Assad’s overthrow would likely produce revenge-taking and a bloodbath far worse than what has happened so far, and whoever gains power in Damascus would be unlikely to put US interests high on the agenda.

The Syrian conflict is also part of a larger civil war in the heart of the Middle East that, in its current phase, began with the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq. In getting rid of Saddam Hussein, the US also deposed a minority Sunni government that had ruled over Iraq’s Shia majority for centuries. Since then, several Sunni Arab states (plus Turkey) have sought to right the balance; their efforts to overthrow the Alawites in Syria are just grist to that mill. But the United States certainly has no interest in becoming party to a Sunni-Shia conflict. Quite the reverse: the US and the West need that conflict to end and at least avoid adding fuel to the fire.

In trying to show Congress that the US is not alone in wanting to punish the Syrian government, the administration is underscoring the strong support of Arab states. They want to enlist the United States as their instrument in overthrowing Syria’s Alawite rule and supplement the arms they have been sending the rebels, buttressed by the intervention of Islamist terrorists, many from their own countries — terrorists who see both the Shia and the West (the US in particular) as enemies.

Why then, make such a matter over “credibility” in Syria? To cut to the chase: the real issue of demonstrating US credibility, today, is not about Syria but about Iran. In addition to setting a red line against Syria’s reported use of chemical weapons, President Obama has regularly pledged to keep Iran from getting nuclear weapons with “all options are on the table.” That is far more serious business because nuclear weapons are much more consequential than chemical weapons. Already, Arab states and Israel are arguing that if Obama does not honor his red line commitment in Syria (a relatively minor concern in international security terms), he might not honor his much more important red line regarding an Iranian bomb.

That argument presumes that the US is incapable of weighing the relative importance of different threats or “red lines.” An Iranian bomb could have much greater consequences for US security (though how much is at least debatable) than what is happening in Syria, and whatever the US does in Syria is unlikely to impact its calculations about Iran’s nuclear program.

The false debate over US credibility in Syria is only part of the problem. More important is whether, in the process of trying to reestablish a prohibition against one weapon of warfare, a US attack will cause the Syrian conflict to spread and draw the US more deeply into the Middle East morass. This could also intensify Israel’s concerns about its security, not just regarding Iran, but in particular about potential Islamist terrorism emanating from “liberated” Syria. The US attack will also undercut the ability of Iran’s new president, Hassan Rouhani, to risk engaging the West diplomatically to end the stalemate over its nuclear program. (The administration and Congress have already done their best to throw cold water on possibilities that might emerge from Rouhani’s election.) And that could increase the chances that, at some point, the US will face the terrible dilemma about whether to attack Iran.

Unfortunately, despite assertions to the contrary, the administration has not adequately attempted to resolve the Syrian conflict through diplomacy. Since early on in the Syrian conflict, Obama said that Bashar al-Assad must go and thus ensured that his government would not negotiate. In his first months as Secretary of State, John Kerry should have devoted himself to Syria; instead he pursued Israeli-Palestinian peacemaking, which every experienced negotiator knows can go nowhere while Israel faces real security challenges on at least three fronts (Syria, Iran and Egypt). And Obama is now in Europe, not trying to put together a Syrian peace process, but rather pursuing his domestic political need to convince Congress that we have strong international support for attacking Syria.

The US will attack Syria. But as it does, the Obama administration needs to focus on business far more important for US interests: beginning, finally, to create a viable, integrated, coherent strategy for the Middle East that recognizes all of its many regional facets and has some chance of success, however long it takes and however difficult the task. That plus a full-court press for diplomacy on Syria is where the US should now place its emphasis, not focusing on punishing the Syrian government which, however successful, won’t lead toward peace and security in the region.

This is what it means to be a great power. This is where US credibility abroad is truly at stake.

]]>by Mark N. Katz

“Obama weighing limited strike on Syria,” reads the main headline of an August 27 Washington Post article. We still don’t know exactly what this will entail, but as this piece — and many other news reports — indicate, the operative word definitely appears to be: limited.

As authors [...]]]>

by Mark N. Katz

“Obama weighing limited strike on Syria,” reads the main headline of an August 27 Washington Post article. We still don’t know exactly what this will entail, but as this piece — and many other news reports — indicate, the operative word definitely appears to be: limited.

As authors Karen De Young and Anne Gearan explain, the action that the Obama administration is contemplating “is designed more to send a message than to cripple Assad’s military and change the balance of forces on the ground.” In other words, after warning last year that the use of chemical weapons is a “red line” that the Assad regime must not cross, President Barack Obama feels that he must respond if (as appears increasingly likely) the Assad regime has used them against its own citizens. But he wants to do as little as possible for fear of getting the US involved in another fractious Middle Eastern conflict.

If this is indeed the sort of attack on Syria that the president is contemplating, it is not likely to be very effective. Bashar al-Assad is not only willing to kill his opponents; he will sacrifice his supporters as well. If the US-led retaliation to his alleged recent use of chemical weapons is just one that targets some of his military facilities, that is a cost that Assad will be willing to pay. Indeed, it may encourage him to launch even more chemical weapons attacks due to the belief that while US retaliation may be annoying, it will not threaten the survival of his regime or its advantages vis-à-vis his opponents.

The White House should not forget that there is precedent for something like this. Between the end of the first Gulf War in 1991 and the US-led intervention against Iraq in 2003, the US launched numerous, small-scale attacks against Iraq in retaliation for Saddam Hussein’s many misdeeds. These did not succeed in improving his behavior much.

Nor will limited (there’s that word again) strikes against Syria improve Assad’s behavior. If the Obama administration seriously wishes to alter Assad’s ways, then it must attack or threaten to attack that which he values most: his and his regime’s survival. It is not clear, of course, that Assad will change course even if he is personally threatened. But it is only if he is eliminated, or appears likely to be, that elements within his security services concerned primarily about their own survival and prosperity will have the opportunity to reach an accommodation with some of the regime’s opponents, neighboring states and the West.

Threatening Assad’s survival is what is needed to attenuate the links between Assad and the forces that are protecting him. Undoubtedly riven with internal rivalries (something that dictators encourage for fear that their subordinates will otherwise collaborate with one another against them), the downfall of Assad — actual or believed to be imminent — is what will open the door for some in the security services to save themselves through cooperating with the regime’s opponents. Absent this condition, it is simply too risky for them to turn against their master and his other supporters — who are ever on the lookout for signs of disloyalty.

So far, though, the Obama administration has taken pains to signal that it is not going to threaten the Assad leadership. This seems very odd. It did, after all, kill Osama bin Laden when it could have captured (and possibly gained a treasure trove of intelligence from) him instead. The Obama administration has also launched an aggressive drone missile campaign against Al Qaeda targets in Yemen, Pakistan and elsewhere. But however heinous the actions of these terrorists have been, they have killed far fewer people than Assad and his henchmen.

The Obama administration may be reluctant to target Assad because he is a head of state. But whether for this reason or any other, the result of Washington’s self-restraint will be that Assad remains free to kill more and more of his own citizens.

An American attack on Syria does indeed need to be limited — limited to Assad.

]]>via IPS News

While some kind of U.S. military action against Syria in the coming days appears increasingly inevitable, the debate over the why and how of such an attack has grown white hot here.

On one side, hawks, who span the political spectrum, argue that President Barack Obama’s credibility [...]]]>

via IPS News

While some kind of U.S. military action against Syria in the coming days appears increasingly inevitable, the debate over the why and how of such an attack has grown white hot here.

On one side, hawks, who span the political spectrum, argue that President Barack Obama’s credibility is at stake, especially now that Secretary of State John Kerry has publicly endorsed the case that the government of President Bashar Al-Assad must have been responsible for the alleged chemical attack on a Damascus suburb that was reported to have killed hundreds of people.

Just one year ago, Obama warned that the regime’s use of such weapons would cross a “red line” and constitute a “game-changer” that would force Washington to reassess its policy of not providing direct military aid to rebels and of avoiding military action of its own.

After U.S. intelligence confirmed earlier this year that government forces had on several occasions used limited quantities of chemical weapons against insurgents, the administration said it would begin providing arms to opposition forces, although rebels complain that nothing has yet materialised.

The hawks have further argued that U.S. military action is also necessary to demonstrate that the most deadly use of chemical weapons since the 1988 Halabja massacre by Iraqi forces against the Kurdish population there – a use of which the US. was fully aware but did not denounce at the time – will not go unpunished.

Military action should be “sufficiently large that it would underscore the message that chemical weapons as a weapon of mass destruction simply cannot be used with impunity,” said Richard Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), told reporters in a teleconference Monday. “The audience here is not just the Syrian government.”

While the hawks, whose position is strongly backed by the governments of Britain, France, Gulf Arab kingdoms and Israel, clearly have the wind at their backs, the doves have not given up.

Remembering Iraq

Recalling the mistakes and distortions of U.S. intelligence in the run-up to the 2003 Iraq War, some argue that the administration is being too hasty in blaming the Syrian government.

If it waits until United Nations inspectors, who visited the site of the alleged attack Monday, complete their work, the United States could at least persuade other governments that Washington is not short-circuiting a multilateral process as it did in Iraq.

Many also note that military action could launch an escalation that Washington will not necessarily be able to control, as noted by a prominent neo-conservative hawk, Eliot Cohen, in Monday’s Washington Post.

“Chess players who think one move ahead usually lose; so do presidents who think they can launch a day or two of strikes and then walk away with a win,” wrote Cohen, who served as counsellor to former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. “The other side, not we, gets to decide when it ends.”

“What if [Obama] hurls cruise missiles at a few key targets, and Assad does nothing and says, ‘I’m still winning.’ What do you then?” asked Col. Lawrence Wilkerson (ret.), who served for 16 years as chief of staff to former Secretary of State Colin Powell. “Do you automatically escalate and go up to a no-fly zone and the challenges that entails, and what then if that doesn’t get [Assad's] attention?

“This is fraught with tar-babiness,” he told IPS in a reference to an African-American folk fable about how Br’er Rabbit becomes stuck to a doll made of tar. “You stick in your hand, and you can’t get it out, so you then you stick in your other hand, and pretty soon you’re all tangled up all this mess – and for what?”

“Certainly there are more vital interests in Iran than in Syria,” he added. “You can’t negotiate with Iran if you start bombing Syria,” he said, a point echoed by the head of the National Iranian American Council, Trita Parsi.

“There is a real opportunity for successful diplomacy on the Iranian nuclear issue, but that opportunity will either be completely spoiled or undermined if the U.S. intervention in Syria puts the U.S. and Iran in direct combat with each other,” he told IPS. Humanitarian concerns and U.S. credibility should also be taken into account when considering intervention, he said.

Remembering Kosovo

Still, the likelihood of military action – almost certainly through the use of airpower since even the most aggressive hawks, such as Republican Senators John McCain and Lindsay Graham, have ruled out the commitment of ground troops – is being increasingly taken for granted here.