by Thomas Lippman

For the United States, Saudi Arabia, other supporters of the rebels in Syria, and for the rebels themselves, this has been a month of fast-paced, intense diplomatic and political activity. It is tempting after so much time and so many deaths to dismiss all the events [...]]]>

by Thomas Lippman

For the United States, Saudi Arabia, other supporters of the rebels in Syria, and for the rebels themselves, this has been a month of fast-paced, intense diplomatic and political activity. It is tempting after so much time and so many deaths to dismiss all the events since mid-January as the inconclusive comings and goings of people who simply don’t know what to do about the intractable conflict, but it’s also possible to add it all up and see the possibility of an emerging new energy, cohesion, and perhaps more effective action.

At the very least, the events and consultations since mid-January seem to have put the United States and Saudi Arabia back on the same page.

A useful point to begin this review is the visit to Washington in mid-January of Prince Muhammad bin Nayef, Saudi Arabia’s minister of interior and the most powerful man in the country other than the king. Nayef, who is respected in Washington for his leadership of Saudi Arabia’s struggle against an al-Qaeda uprising a decade ago, saw everyone in the U.S. national security establishment, plus key members of Congress. Not much was said publicly about the outcome, but within a couple of weeks events began to unfold rapidly.

On Feb. 3, a few days before Prince Muhammad left for Washington, King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia issued a royal decree making it a crime, punishable by prison time, for any Saudi citizen to fight in a foreign conflict. This reflected Riyadh’s concern about the hundreds of young Saudis who have joined extremist rebel groups in Syria and could some day return to make trouble at home. It also was aimed at deflecting criticism from Washington, where some officials have said Riyadh was not doing enough to cut off the flow of fighters.

That same day, Feb. 3, the White House confirmed reports that Obama will visit Saudi Arabia in late March. This has been a difficult year for U.S.-Saudi relations due to disagreements over Iran’s nuclear program and policy toward Egypt, as well as over Syria. Obama’s planned visit is clearly intended to smooth over some of these differences; the conversations would have been more difficult still if the issue of Saudis going to Syria to fight with the jihadi extremists were still on the table.

On Feb. 12, according to the Saudi embassy, Prince Muhammad met with Deputy Secretary of State William Burns and with Under Secretary Wendy Sherman. She holds the administration’s Iran nuclear portfolio and has strongly defended its interim agreement with Tehran, a deal that caused heartburn in Riyadh. While in Washington, Muhammad also met with CIA officials and with the intelligence chiefs of Turkey, Qatar, Jordan and other supporters of the rebels, according to press reports.

Then the pace of events accelerated.

On Feb. 12, King Abdullah II of Jordan, whose country is straining under the burden of supporting Syrian refugees, met with Vice President Joe Biden to discuss “ongoing efforts to bring about a political transition and an end to the conflict in Syria,” the White House said. Two days later, Abdullah conferred with Obama.

On Feb. 15, the UN-brokered peace talks in Geneva ended, predictably, in failure. Secretary of State John Kerry put the blame squarely on the Assad regime’s intransigence, but regardless of who was responsible, that avenue now appears to have come to a dead end.

The next day, the Supreme Military Council of the Free Syrian Army — that is, the non-extremist rebels whom Washington and presumably Riyadh support — announced that Gen. Salam Idriss, the overall military commander who had been increasingly criticized as ineffective, was being replaced. His successor, backed by the Saudis, is Brig. Gen. Abdul-Illah Bashir al-Noeimi. It is too early to know whether he will be able to enlist the support of all the often-divided rebel factions, who are battling extremist forces aligned with al-Qaeda as well as the Syrian army.

Back in Washington, the White House announced on Feb. 18 that Robert Malley, a veteran Middle East hand from the Clinton administration, would return to the National Security Council. His assignment is to manage relations with the often-fractious allies of the Arab Gulf states, a group that includes Saudi Arabia.

A day later, Feb. 19, the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal broke the news that Prince Muhammad bin Nayef had taken over as boss of the kingdom’s effort to arm and strengthen the Free Syrian Army and other non-extremist groups. The Post’s Karen de Young reported the next day that the intelligence chiefs, at their Washington gathering a week earlier, had agreed on how to define which rebel groups were eligible for new aid, and on new arms shipments to them. Muhammad, a firm if low-key operative, replaced the mercurial Prince Bandar bin Sultan, whose personal charisma had evidently not impressed the rebels.

That same day, Feb. 19, Deputy Secretary Burns delivered a speech that was widely depicted as a preview of what Obama will say to King Abdullah next month: the United States is committed to its strategic partnership with the Arab Gulf states, and will not be bamboozled into a permanent agreement with Iran that would leave Tehran with any path to nuclear weapons. Telling the Saudis what they want to hear, Burns said that in Syria, “the simple truth is that there can be no stability and no resolution to the crisis without a transition to a new leadership.” That is, Bashar al-Assad must go, as the Saudis and Obama himself have long demanded, and Riyadh should not interpret the agreement by which Syria is due to give up its chemical weapons as U.S. acquiescence in Assad’s legitimacy.

Meanwhile, of course, Syrians are dying by the thousands as the government continues to bomb civilian areas, and there is no end in sight. Even if Assad steps down, Burns said, the United States has “no illusions” about “the very difficult day after — or, more likely, the very difficult years after.”

Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah are still supporting Assad. It is possible that he could survive to preside over some rump state. But it does appear that the working program of those who want to get rid of him is, at least, less messy and disorganized than it was a month ago.

*This post was revised on Feb. 25 to make an adjustment to the sequence of events.

Photo: Saudi Interior Minister Prince Nayef bin Abdul Aziz al-Saud (left) with Prince Mohammed bin Nayef bin Abdul Azi

]]>via IPS News

If you are confused or baffled by Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy moves over the past month or so, you are hardly alone. It appears the Saudis themselves don’t know quite what to make of the various situations in which they find themselves.

The kingdom’s [...]]]>

via IPS News

If you are confused or baffled by Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy moves over the past month or so, you are hardly alone. It appears the Saudis themselves don’t know quite what to make of the various situations in which they find themselves.

The kingdom’s stated objectives are well known: to get rid of the regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria, curtail Iran’s nuclear ambitions, put a halt to what they see as Iranian troublemaking around the region, and forge a political union among the six members of the Gulf Cooperation Council. None of those goals is within reach under present circumstances — Oman publicly rejected the GCC political union proposal and said it would leave the group if it were accepted — and it is difficult to perceive how Saudi Arabia’s recent tactical moves are going to bring them any closer. At the same time, through intemperate rhetoric and pointless gestures such as rejecting a seat on the UN Security Council that they had long sought, they risk undermining their longstanding security partnership with the United States, the only country strong enough to protect the al-Saud rulers from potential predators around them.

“It’s an ad hoc, shoot from the hip policy that has no strategic vision,” one well-connected analyst observed the other day.

Syria is the biggest and most immediate problem, but hardly the only one. Riyadh’s firm refusal to do business with the al-Maliki government in Iraq has had the effect of making Iraq more dependent on Iran rather than less — the very outcome to which the Saudis say they object. A strong, prosperous Iraq could again be the buffer between Saudi Arabia and Iran that it was under Saddam Hussein, but the Saudis are doing nothing to help Iraq rebuild. They have left that field to Iran.

In another seeming contradiction, Saudi Arabia has been a shrill critic of the interim nuclear agreement between the West and Iran. But at the recent GCC summit conference, the Saudis signed off on a statement from the group endorsing that deal. “The Supreme Council welcomed the interim agreement which was signed by the P 5 +1 with Iran on November 24, 2013 in Geneva,” the official communiqué from that meeting said, “as a preliminary step towards a comprehensive and lasting solution to the Iranian nuclear program that would put an end to concerns on the international and regional level about this program, and enhance the region’s security and stability…” That is pretty much the rationale expressed by the United States and the other members of the negotiating group, a rationale the Saudis have rejected.

In Syria, the Saudis have put themselves in an extremely delicate position. They are all in on the ouster of Assad, and yet after three years of conflict the Syrian leader appears to be gaining strength against the fragmented forces of the rebellion.

Riyadh wants to engineer Assad’s departure, mostly because of his alliance with Iran and Hezbollah, without delivering Syria into the hands of Islamic extremists and jihadists who would impose strict Islamic law on the country and then turn their attention to their neighbors. That is a delicate balance that may not be achievable by remote control from Riyadh.

“It seems that any group, however extreme in its Islamism, is an acceptable party for Saudi support, be it private or public, as long as it does not refer itself as an al-Qaeda offshoot,” observed Jean Francois Seznec, a scholar with wide knowledge of Gulf affairs. In an article written for the Norwegian foreign ministry, Seznec said that the Islamist forces Saudi Arabia is supporting may not be affiliated with al-Qaeda but still “promote a rabid anti-Shi’a and anti-Christian ideology, turning the rest of the world against them and by association against the moderate opposition, and thereby limiting the Saudis’ ability to unite the opposition.”

It may be possible that the groups, backed by enough money from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states and private contributors, can forge themselves into a coherent rebel force that would decisively turn the tide against Assad and then form an inclusive government in Damascus. But given that Assad has his own wealthy supporter, Iran, that seems to be a long shot. Saudi Arabia’s real problem, as Seznec noted, is that despite the billions it has spent on weapons acquisition over decades, it lacks the military power to do anything on its own in Syria. The Kingdom has no force-projection capability, and thus must rely on proxies with dubious credentials.

In a recent interview in TIME, Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif seemed to relish taunting Saudi Arabia about the dangerous game it is playing in Syria. “We are satisfied, totally satisfied, convinced that there is no military solution in Syria and that there is a need to find a political solution in Syria,” he said. “If you want to prevent a void, the types of consequences that we are talking about, I mean if you want to avoid extremism in this region, if you want to prevent a Syria becoming a breeding ground for extremists who will use Syria basically as a staging ground to attack other countries — be it Lebanon, be it Iraq, be it Jordan, Saudi Arabia, even Turkey — these countries are going to be susceptible to a wave of extremism that will find its origins in Syria and the continuation of this tragedy in Syria can only provide the best breeding ground for extremists who use this basically as a justification, as a recruiting climate in order to wage the same type of activity in other parts of this region.” He had a point.

An article in the current issue of Masarat, a journal published by the King Faisal Research Center in Riyadh, said the unwillingness of the U.S. and other western nations to take the field against Assad has left Saudi Arabia with no choice but to adopt more assertive policies and take on wider responsibility for regional stability.

“The Kingdom and its regional allies will increase their support to the Syrian rebels and prevent the collapse of collateral nations like Lebanon and Jordan,” the article said. It called for the creation of a regional security alliance — led, of course, by Saudi Arabia. “It is absolutely vital that a Saudi-led regional project succeed in Syria. The only way the Arab world can make progress is through a collective security framework initially made up of Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and the GCC partner nations.” (Note the omission of Iraq from that wish list.)

The article did not mention that those “GCC partner nations” have never been willing to enter any collective security arrangement that would be dominated by the Saudis, or that Egypt, which has its hands full at home, is in no position to take on new commitments elsewhere. And even if those proposed partners signed on, how long would it take them to put together an operation that could save Syria?

It appears that the Masarat article reflects official thinking because Prince Mohammed Bin Nawaf Bin Abdulaziz, a grandson of the founding king who is the ambassador to Britain, said much the same thing in a column published by the New York Times.

“We believe that many of the West’s policies on both Iran and Syria risk the stability and security of the Middle East. This is a dangerous gamble, about which we cannot remain silent, and will not stand idly by,” the column said.

The west might cut deals with Assad and with the Iranians, the ambassador wrote, but deals with odious and dangerous regimes such as those are strategically dangerous and morally unacceptable. Because of its wealth and its position in Islam, the ambassador said, Saudi Arabia has “enormous responsibilities” throughout the region. “We will act to fulfill these responsibilities, with or without the support of our Western partners.”

Negotiations aimed at stabilizing Syria are scheduled to begin under United Nations auspices on Jan. 22. If they fail to halt the bloodshed, which seems a safe bet, the rebels will expect Saudi Arabia to deliver on its promise. As Americans like to say, good luck with that.

]]>by Barbara Slavin

A new poll following the election of Hassan Rouhani says that a majority of Iranians oppose Iran’s intervention in Syria and Iraq and believe that Iran is seeking nuclear weapons despite their government’s claims to the contrary.

The poll, released Friday (December 6) and conducted August [...]]]>

by Barbara Slavin

A new poll following the election of Hassan Rouhani says that a majority of Iranians oppose Iran’s intervention in Syria and Iraq and believe that Iran is seeking nuclear weapons despite their government’s claims to the contrary.

The poll, released Friday (December 6) and conducted August 26-September 22, of 1,205 Iranians in face-to-face interviews by a subcontractor for Zogby Research Services, also indicated that Rouhani had relatively lukewarm support at the time and that many Iranians would like to see a more democratic political system in their country.

The results jibe with the June presidential elections in which Rouhani won a bare majority of votes, albeit against half a dozen other candidates. Half of those polled after the election either opposed Rouhani or said that his victory would make no difference in their lives. This reporter gained a similar impression of Iranian skepticism about their new president during a visit to Tehran in early August.

Not surprisingly, given the impact of draconian sanctions and mismanagement by the previous Ahmadinejad government on the Iranian economy, the poll found that only 36 percent of Iranians said they were better off now than five years ago, compared to 43 percent who said they were worse off. However, the same percentage — 43 percent — said they expected their lives to improve under the Rouhani administration.

Among the most interesting findings were those related to foreign policy. The poll found that 54 percent believe Iran’s intervention in Syria has had negative consequences – perhaps a reflection of the financial drain on Iran of the war in Syria and of the unpopularity of the Bashar al-Assad regime. Nearly the same proportion of the Iranian population – 52 percent – also opposed Iranian involvement in Iraq, which is ruled by a Shi’ite Muslim government friendly to Tehran. Iranian activities in support of fellow Shi’ites in Lebanon and Bahrain were only slightly more popular, while only in Yemen and Afghanistan did a majority of Iranians say their country’s actions have had a positive impact.

Jim Zogby, director of Zogby Research Services, told IPS that Iranians know “Syria has become a huge problem in the world and they don’t want to have more problems with the world.” The low marks for ties to Iraq may reflect “lingering anti-Iraq sentiment” stemming from the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war, Zogby said.

Iranian attitudes toward democracy and the nuclear issue were also interesting. While a plurality of Iranians (29 percent) listed unemployment as their top priority, a quarter of the population rated advancing democracy first

Other major priorities included:

- Protecting personal and civil rights (23 percent)

- Increasing rights for women (19 percent)

- Ending corruption (18 percent)

- Political or governmental reform (18 percent)

According to the poll, only a tiny fraction – six percent – listed continuing Iran’s uranium enrichment as a top priority. Yet 55 percent agreed with the statement that “my country has ambitions to produce nuclear weapons” compared to 37 percent who believe the government’s assertions that the program is purely peaceful. The Iranian government insists that it is not aiming to produce weapons and signed an agreement in Geneva November 24 to constrain its nuclear program in return for modest sanctions relief.

In a strong show of nationalism, 96 percent said continuing the nuclear program was worth the pain of sanctions. Only seven percent listed resolving the stand-off with the world over the Iranian nuclear program so sanctions could be lifted as their top priority and only five percent put improving relations with the United States and the West at the head of their list.

Zogby said it was not surprising that Iranians would give a low priority to the nuclear program yet “when you push that button [and question Iran’s rights], the nationalism takes off.” He noted those who identified themselves as Rouhani supporters were more inclined to affirm Iran’s right to nuclear weapons than Rouhani opponents — 76 percent compared to 61 percent.

The poll results, Zogby said, suggest that Iranians do not consider Rouhani an exemplar of the reformist Green Movement that convulsed the country during and following 2009 presidential elections, but rather as an establishment figure.

“His supporters are more in the hardline camp,” Zogby said.

]]>Lindsey Graham and John McCain, the two-thirds of the Three Amigos who are still in the U.S. Senate since the departure of Joe Lieberman, contributed to the opinion pages of the Washington Post this weekend a short reprise of their familiar positions on front-burner Middle Eastern [...]]]>

Lindsey Graham and John McCain, the two-thirds of the Three Amigos who are still in the U.S. Senate since the departure of Joe Lieberman, contributed to the opinion pages of the Washington Post this weekend a short reprise of their familiar positions on front-burner Middle Eastern issues: act forcefully to defeat the Assad regime in Syria, be obdurate toward Iran, etc. Nothing new here, but it might be worth reflecting for a moment on one of their accusations: that the administration’s “failure in Syria” is part of broader “collapse of U.S. credibility in the Middle East.” Graham and McCain’s particular usage of the term credibility exemplifies something broader, too: a habit of associating the concept only with forceful actions, especially military actions, rather than with any other policy course.

This restrictive concept of upholding a nation’s credibility does not flow from any dictionary definition of credibility (“the quality or power of inspiring belief”). Whether any given action or piece of inaction tends to inspire belief depends of course on context and on what else the state in question has said or done on the same subject. There is no reason to postulate an asymmetry in favor of forceful action or any other kind of action.

There are valid grounds for criticizing the Obama administration’s policies on Syria, especially the overemphasis on the issue of chemical weapons with insufficient advance thinking about what to do if a significant chemical incident were to occur. But the administration’s subsequent seizing on the Russian initiative after the chemical incident in August was in a real sense a making good on its own word about viewing chemical weapons as the most important dimension of the Syrian conflict. That is an unjustifiably narrow way of viewing the conflict, but at least the administration was being consistent, and consistency is an important ingredient of credibility.

The Two Amigos write that the president “specifically committed” to them in the Oval Office “to degrade the Assad regime’s military capabilities, upgrade the capabilities of the moderate opposition and shift the momentum on the battlefield.” Those of us who have not been flies on the Oval Office wall cannot referee that one. But publicly the president has not made the sort of commitment that would warrant the Amigos’ accusation that he “abandoned” the Syrian opposition.

Another erroneous application of the concept of credibility is the senators’ equating loss of credibility with how “Israel and our Gulf Arab partners are losing all confidence” in the administration’s diplomacy, with references to recent indications of the Saudi regime’s displeasure. Displeasing other states, when there has been no failure to live up to a treaty commitment and when the other states—as is true of both Israel and Saudi Arabia—have major differences of interest with the United States as well as some shared interests, has nothing to do with a failure of credibility. Consistent pursuit of the United States’s own interests is much more of a foundation for maintaining credibility.

Graham and McCain do inadvertently give us an example in their piece of how U.S. credibility can be hurt. In referring to the Iranian nuclear issue they say, “We should be prepared to suspend the implementation of new sanctions, but only if Iran suspends its enrichment activities.” This formulation comes out of a letter that eight other senators also signed and that tries to portray this package as a balanced “suspension for suspension” deal. This is a ludicrous play on words. There is nothing reasonable or proportionate about linking a demand for one side to stop completely an ongoing program in return for the other side not piling on still more new sanctions, which doesn’t really entail a suspension of anything. The wordplay is unbelievable. If we want the Iranians or anyone else to believe that the United States is serious about reaching an agreement, this sort of silliness damages U.S. credibility.

]]>via Tom Dispatch

The abiding defect of U.S. foreign policy? It’s isolationism, my friend. Purporting to steer clear of war, isolationism fosters it. Isolationism impedes the spread of democracy. It inhibits trade and therefore prosperity. It allows evildoers to get [...]]]>

via Tom Dispatch

The abiding defect of U.S. foreign policy? It’s isolationism, my friend. Purporting to steer clear of war, isolationism fosters it. Isolationism impedes the spread of democracy. It inhibits trade and therefore prosperity. It allows evildoers to get away with murder. Isolationists prevent the United States from accomplishing its providentially assigned global mission. Wean the American people from their persistent inclination to look inward and who knows what wonders our leaders will accomplish.

The United States has been at war for well over a decade now, with U.S. attacks and excursions in distant lands having become as commonplace as floods and forest fires. Yet during the recent debate over Syria, the absence of popular enthusiasm for opening up another active front evoked expressions of concern in Washington that Americans were once more turning their backs on the world.

As he was proclaiming the imperative of punishing the government of Bashar al-Assad, Secretary of State John Kerry also chided skeptical members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that “this is not the time for armchair isolationism.” Commentators keen to have a go at the Syrian autocrat wasted little time in expanding on Kerry’s theme.

Reflecting on “where isolationism leads,” Jennifer Rubin, the reliably bellicose Washington Post columnist, was quick to chime in, denouncing those hesitant to initiate another war as “infantile.” American isolationists, she insisted, were giving a green light to aggression. Any nation that counted on the United States for protection had now become a “sitting duck,” with “Eastern Europe [and] neighbors of Venezuela and Israel” among those left exposed and vulnerable. News reports of Venezuelan troop movements threatening Brazil, Colombia, or Guyana were notably absent from the Post or any other media outlet, but no matter — you get the idea.

Military analyst Frederick Kagan was equally troubled. Also writing in thePost, he worried that “the isolationist narrative is rapidly becoming dominant.” His preferred narrative emphasized the need for ever greater military exertions, with Syria just the place to launch a new campaign. For Bret Stephens, a columnist with the Wall Street Journal, the problem was the Republican Party. Where had the hawks gone? The Syria debate, he lamented, was “exposing the isolationist worm eating its way through the GOP apple.”

The Journal’s op-ed page also gave the redoubtable Norman Podhoretz, not only still alive but vigorously kicking, a chance to vent. Unmasking President Obama as “a left-wing radical” intent on “reduc[ing] the country’s power and influence,” the unrepentant neoconservative accused the president of exploiting the “war-weariness of the American people and the rise of isolationist sentiment… on the left and right” to bring about “a greater diminution of American power than he probably envisaged even in his wildest radical dreams.”

Obama escalated the war in Afghanistan, “got” Osama bin Laden, toppled one Arab dictator in Libya, and bashed and bombed targets in Somalia, Yemen, Pakistan, and elsewhere. Even so, it turns out he is actually part of the isolationist conspiracy to destroy America!

Over at the New York Times, similar concerns, even if less hysterically expressed, prevailed. According to Times columnist Roger Cohen, President Obama’s reluctance to pull the trigger showed that he had “deferred to a growing isolationism.” Bill Keller concurred. “America is again in a deep isolationist mood.” In a column entitled, “Our New Isolationism,” he decried “the fears and defeatist slogans of knee-jerk isolationism” that were impeding military action. (For Keller, the proper antidote to isolationism is amnesia. As he put it, “Getting Syria right starts with getting over Iraq.”)

For his part, Times staff writer Sam Tanenhaus contributed a bizarre two-minute exercise in video agitprop — complete with faked scenes of the Japanese attacking Pearl Harbor — that slapped the isolationist label on anyone opposing entry into any war whatsoever, or tiring of a war gone awry, or proposing that America go it alone.

When the “New Isolationism” Was New

Most of this, of course, qualifies as overheated malarkey. As a characterization of U.S. policy at any time in memory, isolationism is a fiction. Never really a tendency, it qualifies at most as a moment, referring to that period in the 1930s when large numbers of Americans balked at the prospect of entering another European war, the previous one having fallen well short of its “War To End All Wars” advance billing.

In fact, from the day of its founding down to the present, the United States has never turned its back on the world. Isolationism owes its storied history to its value as a rhetorical device, deployed to discredit anyone opposing an action or commitment (usually involving military forces) that others happen to favor. If I, a grandson of Lithuanian immigrants, favor deploying U.S. forces to Lithuania to keep that NATO ally out of Vladimir Putin’s clutches and you oppose that proposition, then you, sir or madam, are an “isolationist.” Presumably, Jennifer Rubin will see things my way and lend her support to shoring up Lithuania’s vulnerable frontiers.

For this very reason, the term isolationism is not likely to disappear from American political discourse anytime soon. It’s too useful. Indeed, employ this verbal cudgel to castigate your opponents and your chances of gaining entrée to the nation’s most prestigious publications improve appreciably. Warn about the revival of isolationism and your prospects of making the grade as a pundit or candidate for high office suddenly brighten. This is the great thing about using isolationists as punching bags: it makes actual thought unnecessary. All that’s required to posture as a font of wisdom is the brainless recycling of clichés, half-truths, and bromides.

No publication is more likely to welcome those clichés, half-truths, and bromides than the New York Times. There, isolationism always looms remarkably large and is just around the corner.

In July 1942, the New York Times Magazine opened its pages to Vice President Henry A. Wallace, who sounded the alarm about the looming threat of what he styled a “new isolationism.” This was in the midst of World War II, mind you.

After the previous world war, the vice president wrote, the United States had turned inward. As summer follows spring, “the choice led up to this present war.” Repeat the error, Wallace warned, and “the price will be more terrible and will be paid much sooner.” The world was changing and it was long past time for Americans to get with the program. “The airplane, the radio, and modern technology have bound the planet so closely together that what happens anywhere on the planet has a direct effect everywhere else.” In a world that had “suddenly become so small,” he continued, “we cannot afford to resume the role of hermit.”

The implications for policy were self-evident:

“This time, then, we have only one real choice. We must play a responsible part in the world — leading the way in world progress, fostering a healthy world trade, helping to protect the world’s peace.”

One month later, it was Archibald MacLeish’s turn. On August 16, 1942, theTimes magazine published a long essay of his under the title of — wouldn’t you know it — “The New Isolationism.” For readers in need of coaching, Timeseditors inserted this seal of approval before the text: “There is great pertinence in the following article.”

A well-known poet, playwright, and literary gadfly, MacLeish was at the time serving as Librarian of Congress. From this bully pulpit, he offered the reassuring news that “isolationism in America is dead.” Unfortunately, like zombies, “old isolationists never really die: they merely dig in their toes in a new position. And the new position, whatever name is given it, is isolation still.”

Fortunately, the American people were having none of it. They had “recaptured the current of history and they propose to move with it; they don’t mean to be denied.” MacLeish’s fellow citizens knew what he knew: “that there is a stirring in our world…, a forward thrusting and overflowing human hope of the human will which must be given a channel or it will dig a channel itself.” In effect, MacLeish was daring the isolationists, in whatever guise, to stand in the way of this forward thrusting and overflowing hopefulness. Presumably, they would either drown or be crushed.

Fortunately, the American people were having none of it. They had “recaptured the current of history and they propose to move with it; they don’t mean to be denied.” MacLeish’s fellow citizens knew what he knew: “that there is a stirring in our world…, a forward thrusting and overflowing human hope of the human will which must be given a channel or it will dig a channel itself.” In effect, MacLeish was daring the isolationists, in whatever guise, to stand in the way of this forward thrusting and overflowing hopefulness. Presumably, they would either drown or be crushed.

The end of World War II found the United States donning the mantle of global leadership, much as Wallace, MacLeish, and the Times had counseled. World peace did not ensue. Instead, a host of problems continued to afflict the planet, with isolationists time and again fingered as the culprits impeding their solution.

The Gift That Never Stops Giving

In June 1948, with a notable absence of creativity in drafting headlines, theTimes once again found evidence of “the new isolationism.” In an unsigned editorial, the paper charged that an American penchant for hermit-like behavior was “asserting itself again in a manner that is both distressing and baffling.” With the Cold War fully joined and U.S. forces occupying Germany, Japan, and other countries, the Times worried that some Republicans in Congress appeared reluctant to fund the Marshall Plan.

From their offices in Manhattan, members of the Times editorial board detected in some quarters “a homesickness for the old days.” It was incumbent upon Americans to understand that “the time is past when we could protect ourselves easily behind our barriers behind the seas.” History was summoning the United States to lead the world: “The very success of our democracy has now imposed duties upon us which we must fulfill if that democracy is to survive.” Those entertaining contrary views, the Times huffed, “do not speak for the American people.”

That very month, Josef Stalin announced that the Soviet Union was blockading Berlin. The U.S. responded not by heading for the exits but by initiating a dramatic airlift. Oh, and Congress fully funded the Marshall Plan.

Barely a year later, in August 1949, with Stalin having just lifted the Berlin Blockade, Times columnist Arthur Krock discerned another urge to disengage. In a piece called “Chickens Usually Come Home,” he cited congressional reservations about the recently promulgated Truman Doctrine as evidence of, yes, a “new isolationism.” As it happened, Congress duly appropriated the money President Truman was requesting to support Greece and Turkey against the threat of communism — as it would support similar requests to throw arms and money at other trouble spots like French Indochina.

Even so, in November of that year, the Times magazine published yet another warning about “the challenge of a new isolationism.” The author was Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson, then positioning himself for a White House run. Like many another would-be candidate before and since, Stevenson took the preliminary step of signaling his opposition to the I-word.

World War II, he wrote, had “not only destroyed fascism abroad, but a lot of isolationist notions here at home.” War and technological advance had “buried the whole ostrich of isolation.” At least it should have. Unfortunately, some Republicans hadn’t gotten the word. They were “internationally minded in principle but not in practice.” Stevenson feared that when the chips were down such head-in-the-sand inclinations might come roaring back. This he was determined to resist. “The eagle, not the ostrich,” he proclaimed, “is our national emblem.”

In August 1957, the Times magazine was at it once again, opening its pages to another Illinois Democrat, Senator Paul Douglas, for an essay familiarly entitled “A New Isolationism — Ripples or Tide?” Douglas claimed that “a new tide of isolationism is rising in the country.” U.S. forces remained in Germany and Japan, along with Korea, where they had recently fought a major war. Even so, the senator worried that “the internationalists are tiring rapidly now.”

Americans needed to fortify themselves by heeding the message of the Gospels: “Let the spirit of the Galilean enter our worldly and power-obsessed hearts.” In other words, the senator’s prescription for American statecraft was an early version of What Would Jesus Do? Was Jesus Christ an advocate of American global leadership? Senator Douglas apparently thought so.

Then came Vietnam. By May 1970, even Times-men were showing a little of that fatigue. That month, star columnist James Reston pointed (yet again) to the “new isolationism.” Yet in contrast to the paper’s scribblings on the subject over the previous three decades, Reston didn’t decry it as entirely irrational. The war had proven to be a bummer and “the longer it goes on,” he wrote, “the harder it will be to get public support for American intervention.” Washington, in other words, needed to end its misguided war if it had any hopes of repositioning itself to start the next one.

A Concept Growing Long in the Tooth

By 1980, the Times showed signs of recovering from its brief Vietnam funk. In a review of Norman Podhoretz’s The Present Danger, for example, the noted critic Anatole Broyard extolled the author’s argument as “dispassionate,” “temperate,” and “almost commonsensical.”

The actual text was none of those things. What the pugnacious Podhoretz called — get ready for it — “the new isolationism” was, in his words, “hard to distinguish from simple anti-Americanism.” Isolationists — anyone who had opposed the Vietnam War on whatever grounds — believed that the United States was “a force for evil, a menace, a terror.” Podhoretz detected a “psychological connection” between “anti-Americanism, isolationism, and the tendency to explain away or even apologize for anything the Soviet Union does, no matter how menacing.” It wasn’t bad enough that isolationists hated their country, they were, it seems, commie symps to boot.

Fast forward a decade, and — less than three months after U.S. troops invaded Panama – Times columnist Flora Lewis sensed a resurgence of you-know-what. In a February 1990 column, she described “a convergence of right and left” with both sides “arguing with increasing intensity that it’s time for the U.S. to get off the world.” Right-wingers saw that world as too nasty to save; left-wingers, the United States as too nasty to save it. “Both,” she concluded (of course), were “moving toward a new isolationism.”

Five months later, Saddam Hussein sent his troops into Kuwait. Instead of getting off the world, President George H.W. Bush deployed U.S. combat forces to defend Saudi Arabia. For Joshua Muravchik, however, merely defending that oil-rich kingdom wasn’t nearly good enough. Indeed, here was a prime example of the “New Isolationism, Same Old Mistake,” as his Timesop-ed was entitled.

The mistake was to flinch from instantly ejecting Saddam’s forces. Although opponents of a war against Iraq did not “see themselves as isolationists, but as realists,” he considered this a distinction without a difference. Muravchik, who made his living churning out foreign policy analysis for various Washington think tanks, favored “the principle of investing America’s power in the effort to fashion an environment congenial to our long-term safety.” War, he firmly believed, offered the means to fashion that congenial environment. Should America fail to act, he warned, “our abdication will encourage such threats to grow.”

Of course, the United States did act and the threats grew anyway. In and around the Middle East, the environment continued to be thoroughly uncongenial. Still, in Times-world, the American penchant for doing too little rather than too much remained the eternal problem, eternally “new.” An op-edby up-and-coming journalist James Traub appearing in the Times in December 1991, just months after a half-million U.S. troops had liberated Kuwait, was typical. Assessing the contemporary political scene, Traub detected “a new wave of isolationism gathering force.” Traub was undoubtedly establishing his bona fides. (Soon after, he landed a job working for the paper.)

This time, according to Traub, the problem was the Democrats. No longer “the party of Wilson or of John F. Kennedy,” Democrats, he lamented, “aspire[d] to be the party of middle-class frustrations — and if that entails turning your back on the world, so be it.” The following year Democrats nominated as their presidential candidate Bill Clinton, who insisted that he would never under any circumstances turn his back on the world. Even so, no sooner did Clinton win than Times columnist Leslie Gelb was predicting that the new president would “fall into the trap of isolationism and policy passivity.”

Get Me Rewrite!

Arthur Schlesinger defined the problem in broader terms. The famous historian and Democratic Party insider had weighed in early on the matter with a much-noted essay that appeared in The Atlantic Monthly back in 1952. He called it – you guessed it — “The New Isolationism.”

In June 1994, more than 40 years later, with the Cold War now finally won, Schlesinger was back for more with a Times op-ed that sounded the usual alarm. “The Cold War produced the illusion that traditional isolationism was dead and buried,” he wrote, but of course — this is, after all, the Times – it was actually alive and kicking. The passing of the Cold War had “weakened the incentives to internationalism” and was giving isolationists a new opening, even though in “a world of law requiring enforcement,” it was incumbent upon the United States to be the lead enforcer.

The warning resonated. Although the Times does not normally givecommencement addresses much attention, it made an exception for Madeleine Albright’s remarks to graduating seniors at Barnard College in May 1995. The U.S. ambassador to the United Nations had detected what she called “a trend toward isolationism that is running stronger in America than at any time since the period between the two world wars,” and the American people were giving in to the temptation “to pull the covers up over our heads and pretend we do not notice, do not care, and are unaffected by events overseas.” In other circumstances in another place, it might have seemed an odd claim, given that the United States had just wrapped up armed interventions in Somalia and Haiti and was on the verge of initiating a bombing campaign in the Balkans.

Still, Schlesinger had Albright’s back. The July/August 1995 issue of Foreign Affairs prominently featured an article of his entitled “Back to the Womb? Isolationism’s Renewed Threat,” with Times editors publishing a CliffsNotes version on the op-ed page a month earlier. “The isolationist impulse has risen from the grave,” Schlesinger announced, “and it has taken the new form of unilateralism.”

His complaint was no longer that the United States hesitated to act, but that it did not act in concert with others. This “neo-isolationism,” he warned, introducing a new note into the tradition of isolationism-bashing for the first time in decades, “promises to prevent the most powerful nation on the planet from playing any role in enforcing the peace system.” The isolationists were winning — this time through pure international belligerence. Yet “as we return to the womb,” Schlesinger warned his fellow citizens, “we are surrendering a magnificent dream.”

Other Times contributors shared Schlesinger’s concern. On January 30, 1996, the columnist Russell Baker chipped in with a piece called “The New Isolationism.” For those slow on the uptake, Jessica Mathews, then a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, affirmed Baker’s concerns by publishing anidentically titled column in the Washington Post a mere six days later. Mathews reported “troubling signs that the turning inward that many feared would follow the Cold War’s end is indeed happening.” With both the Times and the Post concurring, “the new isolationism” had seemingly reached pandemic proportions (as a title, if nothing else).

Did the “new” isolationism then pave the way for 9/11? Was al-Qaeda inspired by an unwillingness on Washington’s part to insert itself into the Islamic world?

Unintended and unanticipated consequences stemming from prior U.S. interventions might have seemed to offer a better explanation. But this much is for sure: as far as the Times was concerned, even in the midst of George W. Bush’s Global War in Terror, the threat of isolationism persisted.

In January 2004, David M. Malone, president of the International Peace Academy, worried in a Times op-ed “that the United States is retracting into itself” — this despite the fact that U.S. forces were engaged in simultaneous wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Among Americans, a concern about terrorism, he insisted, was breeding “a sense of self-obsession and indifference to the plight of others.” “When Terrorists Win: Beware America’s New Isolationism,” blared the headline of Malone’s not-so-new piece.

Actually, Americans should beware those who conjure up phony warnings of a “new isolationism” to advance a particular agenda. The essence of that agenda, whatever the particulars and however packaged, is this: If the United States just tries a little bit harder — one more intervention, one more shipment of arms to a beleaguered “ally,” one more line drawn in the sand — we will finally turn the corner and the bright uplands of peace and freedom will come into view.

This is a delusion, of course. But if you write a piece exposing that delusion, don’t bother submitting it to the Times.

Andrew J. Bacevich is a professor of history and international relations at Boston University. His new book is Breach of Trust: How Americans Failed Their Soldiers and Their Country.

Copyright 2013 Andrew Bacevich

]]>It’s too early to tell yet whether Russia’s initiative has removed the threat of a U.S. strike on Syria over the alleged use of chemical weapons. While the signs are as good as could be hoped for at this point, a lot can happen in the upcoming weeks. And, whatever the final [...]]]>

It’s too early to tell yet whether Russia’s initiative has removed the threat of a U.S. strike on Syria over the alleged use of chemical weapons. While the signs are as good as could be hoped for at this point, a lot can happen in the upcoming weeks. And, whatever the final disposition of a U.S. strike on Syria, the plight of the Syrian people, which has played almost no substantive part in this debate and has largely been reduced to a propaganda tool for whomever is making their case today, isn’t going to be affected much one way or the other.

But we have already seen enough to determine some winners and losers in this political drama:

AIPAC: Loser The major pro-Israel lobbying organization made a serious mistake by taking their advocacy for a strike on Syria to such a public forum. It would have been easy enough for them to quietly bring their lobbyists to the Hill and advocate their position. The decision to do so as loudly as they did is puzzling to say the least. It seems pretty clear that the Obama administration actually recruited AIPAC to try to drum up support for their position. The extremely powerful lobbying group had followed Israel’s lead and stayed generally silent on Syria until Obama’s announcement of a strike, then suddenly dove in with both feet.

It didn’t work. Based on reports, it seems clear that the lobbyists were less than enthusiastic and their efforts didn’t sway lawmakers. AIPAC’s attempts to keep Israel out of it also failed. They were scrupulous about not mentioning Israel’s security in their talking points, but the very presence of a lobbying group whose raison d’être is protecting Israel’s interests overwhelmed that attempt. AIPAC thought it could separate itself, in the public eye and on this one issue, from Israel, but that was a fool’s game. It doesn’t help that it was untrue that this was not about Israel. While Israel would surely prefer that Syria not have any chemical or biological weapons, whatever the outcome of the civil war, it’s not that high a priority for them.

But Iran is. Part of the case for a Syria strike has been the notion that backing off would show weakness and embolden Iran in its alleged quest for nuclear weapons. Israel, therefore, backed Obama’s decision, but this wasn’t a compelling reason for it to get publicly involved in the domestic quarrel over the strike. Indeed, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was said to have made a few phone calls to allies on the Hill, but it was clear from the outset that he had learned well the lessons from the 2012 election about being seen as meddling too much in domestic US politics. He cannot be happy with AIPAC’s strategy here of doing this so loudly and publicly.

Between the bad strategy and the ineffectiveness of their lobbying, at least for now, AIPAC takes a hit here. It’s by no means a crippling one, but it is significant. When the issue can be framed in terms of Israeli security, there is little doubt AIPAC will have as much sway as always, and when the issue is not one that the U.S. public feels strongly about, their ability to move campaign contributions will have the same impact it has had before. But every time AIPAC is seen to be advocating policy for the U.S. based on Israeli interests, the lobby takes a hit. Enough of those over time will erode its dominance.

John Kerry: loser If Kerry was still an elected official, this might be a different score. But he is a diplomat now and his standing on the world stage was clearly diminished by his actions in this drama. He gets the benefit of it being better to be lucky than good, as his now-famous gaffe ended up being exactly the plan Russia put forth for averting a U.S. strike. But few, aside from fawning Obama boosters, are buying that this was a plan. If it were, the State Department wouldn’t have immediately walked back the statement; it would have waited to see if Russia would “take the bait.” Kerry has come off in all of this as looking all too similar to his predecessors in the Bush administration, talking of conclusive proof while U.S. military and intelligence officials said that his evidence was far from a “slam-dunk.” Kerry is now trumpeting the upcoming UN report that is expected to conclusively state that chemical weapons were used. But everyone, with the exception of a marginal few, believes that already. The question is whether the Assad regime carried out the attack under Assad’s authority. That is far less clear, and the UN does not appear to be stating that conclusion. The evidence thus far suggests that, while Assad having ordered the chemical attack remains a distinct possibility, it is at least as possible that the attack was perpetrated by a rogue commander who had access to the weapons, and against Assad’s wishes.

In any case, Kerry’s eagerness for this attack, and his disregard for international law and process, contrasts starkly with the Obama administration’s stated preference to act differently from its predecessor. Kerry’s standing in the U.S. can easily recover from this, but in the international arena, which is where he works, it is going to be much tougher.

Barack Obama: loser Obama has been in a tough position regarding Syria. He surely does not want to get involved there; such action stands in stark contrast to his desired “pivot to Asia,” as well as his promise to “end wars, not to start them.” And he is as aware as anyone else that the U.S. has little national security interest in Syria. Moreover, despite his opposition to Assad, the U.S. is less than enamored over the prospects of a Syria after Assad, which is likely to be the scene of further battles for supremacy that are very likely to lead to regimes we are not any more in sync with than we are with Assad, quite possibly a good deal less.

But his “red line” boxed him in. It was his credibility, more than the United States’ that was at stake here, and it takes a hit. While it is highly unlikely that anyone in Tehran is changing their view of the U.S. and their own strategic position because of this, it is true that this will shake the confidence of Israel, Saudi Arabia, the al-Sisi government in Egypt and other U.S. allies in the region. That might be good in the long run, but in the short term, it will harm Obama’s maneuverability in the region.

Domestically, Obama reinforced his image as a weak and indecisive leader on foreign policy; his appeal to Congress pleased some of his supporters, but few others were impressed. He has been blundering around the Middle East for five years now, and he doesn’t seem to be getting any better at it, which is discouraging, to say the least.

Vladimir Putin: winner Putin comes out of this in a great position. He really doesn’t care if Assad stays or goes as long as Syria (or what’s left of it) remains in the Russian camp. Acting to forestall or possibly even prevent a U.S. strike on another Arab country will score him points in the region, although after Russia’s actions in Chechnya, he’ll never be terribly popular in the Muslim world. Still, capitalizing on the even deeper mistrust of the United States can get him a long way, and this episode is going to help a lot in the long run. More immediately, it helps Putin set up a diplomatic process that includes elements of the Assad regime, something he has been after for a long time but the rebels have staunchly opposed. With the U.S. now on the diplomatic defensive, he might be able to get it done, especially as war-weariness in Syria grows.

Israel: winner Israel has stayed out of the debate to a large degree. Their rebuke of AIPAC and their public silence on the U.S. debate has helped erase the memory of Netanyahu’s clumsy interference on behalf of his friend, Mitt Romney a year ago. Israel is in no hurry to see the civil war in Syria end, as the outcome is unlikely to be in its favor whichever side wins. And, while all eyes are on Syria no one is paying attention to Palestinian complaints about the failing peace talks. That makes it even easier for Israel to comply with U.S. wishes and keep silent about the talks, planting seeds for blaming the Palestinians for the talks’ inevitable failure. Unlike Obama, Netanyahu seems to be learning from his mistakes, which is not a pleasant prospect for the Palestinians.

Iran: winner While it’s true that the Syria controversy will have little impact on the U.S.-Iran standoff, the show of intense reluctance to stretch the U.S. military arm out again can’t help but please Tehran. It doesn’t hurt either that when, a few days ago, the U.S. tried to appease Israel by mumbling about some “troublesome” things regarding the Iranian nuclear problem, no one took it very seriously and hopes remain high that President Hassan Rouhani will change the course of the standoff. Russia’s maneuvers to keep Syria within its sphere of influence bode well for Iran as well.

The Syrian people: slight winners A U.S. strike would have almost certainly caused an escalation in the Assad regime’s conventional warfare in Syria. Ninety-nine percent of the deaths and refugees have been caused by conventional weapons — that was a good reason for the U.S. not to do it. But increased momentum behind the Russian push is also likely to ensure the war goes on for some time and this increases chances that remnants of the current regime will remain in place at the end of it, even if Assad himself is ousted. Now that the U.S. is determined to arm the rebels to a greater degree, an increasing war of attrition is more likely and that bodes very ill for the people caught in the middle. Considering that some one-third of the population is now either internally displaced or seeking refuge in other countries and a death toll of over 110,000, one must consider avoiding an escalation a victory for these beleaguered people. But outside intervention to stop the killing seems as remote as ever, and the hopes for an international conference to try to settle the conflict are advanced by this episode a bit, but are still uncertain at best.

-Photo: U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry directs a comment to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu after a meeting that touched on Middle East peace talks and Syrian chemical weapons, in Jerusalem on September 15, 2013. Credit: State Department

]]>via USIP

Iran has mixed feelings and conflicting interests in the Syrian crisis. Tehran has a strategic interest in opposing chemical weapons due to its own horrific experience during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. For years, President Saddam Hussein’s military used chemical weapons that killed thousands of Iranian soldiers. So [...]]]>

via USIP

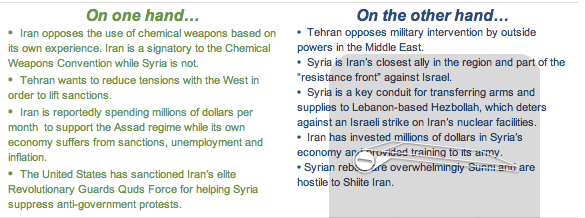

Iran has mixed feelings and conflicting interests in the Syrian crisis. Tehran has a strategic interest in opposing chemical weapons due to its own horrific experience during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. For years, President Saddam Hussein’s military used chemical weapons that killed thousands of Iranian soldiers. So Iran actually shares interests with the United States, European nations and the Arab League in opposing any use of chemical weapons.

But the Islamic Republic also has compelling reasons to continue supporting Damascus. The Syrian regime is Iran’s closest ally in the Middle East and the geographic link to its Hezbollah partners in Lebanon. As a result, Tehran vehemently opposes U.S. intervention or any action that might change the military balance against President Bashar Assad.

The Iran-Syria alliance is more than a marriage of convenience. Tehran and Damascus have common geopolitical, security, and economic interests. Syria was one of only two Arab nations (the other being Libya) to support Iran’s fight against Saddam Hussein, and it was an important conduit for weapons to an isolated Iran. Furthermore, Hafez Assad, Bashar’s father, allowed Iran to help create Hezbollah, the Shiite political movement in Lebanon. Its militia, trained by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, has been an effective tool against Syria’s archenemy, Israel.

Relations between Tehran and Damascus have been rocky at times. Hafez Assad clashed with Hezbollah in Lebanon and was wary of too much Iranian involvement in his neighborhood. But his death in 2000 reinvigorated the Iran-Syria alliance. Bashar Assad has been much more enthusiastic about Iranian support, especially since Hezbollah’s “victorious” 2006 conflict with Israel.

In the last decade, Iran’s Revolutionary Guards have trained, equipped, and at times even directed Syria’s security and military forces. Hundreds of thousands of Iranian pilgrims and tourists visited Syria before its civil war, and Iranian companies made significant investments in the Syrian economy.

Fundamentalist figures within the Guards view Syria as the “front line” of Iranian resistance against Israel and the United States. Without Syria, Iran would not be able to supply Hezbollah effectively, limiting its ability to help its ally in the event of a war with Israel. Hezbollah wields thousands of rockets able to strike Israel, providing Iran deterrence against Israel — especially if Tel Aviv chose to strike Iran’s nuclear facilities. A weakened Hezbollah would directly impact Iran’s national security. Syria’s loss could also tip the balance in Iran’s rivalry with Saudi Arabia, making the Wahhabi kingdom one of the most influential powers in the Middle East.

In the run up to a U.S. decision on military action against Syria, Iranian leaders appeared divided.

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and hardline lawmakers reacted with alarm to possible U.S. strikes against the Assad regime. And Revolutionary Guards commanders threatened to retaliate against U.S. interests. The hardliners clearly viewed the Assad regime as an asset worth defending as of September 2013.

But President Hassan Rouhani, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif and former President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani adopted a more critical line on Syria. “We believe that the government in Syria has made grave mistakes that have, unfortunately, paved the way for the situation in the country to be abused,” Zarif told a local publication in September 2013.

Rafsanjani, still an influential political figure, reportedly said that the Syrian government gassed its own people. This was a clear breach of official Iranian policy, which has blamed the predominantly Sunni rebels. Rafsanjani’s words suggested that he viewed unconditional support for Assad as a losing strategy. His remark also earned a rebuke from Khamenei, who warned Iranian officials against crossing the “principles and red lines” of the Islamic Republic. Khamenei’s message may have been intended for Rouhani’s government, which is closely aligned with Rafsanjani and seems to increasingly view the Syrian regime as a liability.

Regardless, a significant section of Iran’s political elite could be amenable to engaging the United States on Syria. Both sides have a common interest: preventing Sunni extremists from coming to power in Damascus. Iran and the United States also prefer a negotiated settlement over military intervention to solve the crisis. Tehran might need to be included in a settlement given its influence in Syria. Negotiating with Iran on Syria could ultimately help America’s greater goal of a diplomatic breakthrough, not only on Syria but Tehran’s nuclear program as well.

– Alireza Nader is a senior international policy analyst at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation.

*Read Alireza Nader’s chapter on the Revolutionary Guards in “The Iran Primer”

Photo Credits: Bashar Assad and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei via Leader.ir, Syria graphic via Khamenei.ir Facebook

]]>by Jasmin Ramsey

You’re no doubt aware by now of a proposal by Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov for Syria to hand over its (still only accidentally acknowledged) chemical weapons to international control, which his Syrian counterpart Walid al-Moualem said Syria “welcomes”. Syrian ally Russia was jumpstarted into action after [...]]]>

by Jasmin Ramsey

You’re no doubt aware by now of a proposal by Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov for Syria to hand over its (still only accidentally acknowledged) chemical weapons to international control, which his Syrian counterpart Walid al-Moualem said Syria “welcomes”. Syrian ally Russia was jumpstarted into action after Secretary of State John Kerry apparently went off script in London today by floating the proposal (suggested over a year ago by former Senator Richard G. Lugar) and doubting its feasibility in the same sentence after CBS reporter Margaret Brennan asked if there was any way Syria could avert military action:

Sure, if he could turn over every single bit of his chemical weapons to the international community, in the next week, turn it over. All of it, without delay and allow a full and total accounting for that, but he isn’t about to do it and it can’t be done, obviously.

Novelist Teju Cole has broken all this down for us in Twitter-speak

Kerry: We won’t attack…if you do this impossible thing. Syria: Oh? We’ll do it. Russia: They’ll do it. UN: They’ll do it. Kerry: Shit!

— Teju Cole (@tejucole) September 9, 2013

While it’s too soon to get excited with the proposal’s details still in the making, Kerry’s words have taken on a life of their own (though some have suggested this was at least somehow related to a behind-the-scenes diplomatic maneuver). The State Department and White House seem to have forgotten to talk to each other before issuing statements on all this earlier today. State Department Deputy Spokesperson Marie Harf called Kerry’s words “hypothetical” and “rhetorical” and said the Russian proposal was considered “highly unlikely”. She also — wait for this — categorically stated that “the Secretary was not making a proposal.” Later the White House said during its daily press briefing that it would take a “hard look” at the Russian proposal, but Press Secretary Jay Carney also repeatedly emphasized that all this would not have occurred without the credible threat of force against President Bashar al-Assad’s alleged actions. He meanwhile urged Congress to vote for an Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) against Syria, which the administration has been strongly pushing for, and which Kerry’s words may have now endangered.

Speaking at the White House during a Forum to Combat Wildlife Trafficking immediately after Carney’s appearance, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said she had just met with President Obama and seemed to have the most updated speech on the issue:

…if the regime immediately surrendered its stockpiles to international control as was suggested by Secretary Kerry and the Russians, that would be an important step. But this cannot be another excuse for delay or obstruction.

While many are labelling Kerry’s words a “gaffe”, Clinton strategically tried to frame it as a purposeful move by Kerry, being forced, of course, to include the Russians. Perhaps the White House is hoping everyone will eventually forget Harf’s opposing description.

In any case, here’s Deputy National Security Advisor for Strategic Communications and Speechwriting Ben Rhodes with the most recent WH statement:

US will review Russian proposal. We want Syrian CW under intl control. Important that this only proposed bc credible threat of mil action

— Ben Rhodes (@rhodes44) September 9, 2013

It should also be noted that earlier in the day UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon had said following the Russian announcement that he was “considering urging the Security Council to demand the immediate transfer of Syria’s chemical weapons and chemical precursor stocks to places inside Syria where they can be safely stored and destroyed” if it was proven that chemical weapons have been used.

It will be interesting to see how Obama tackles all this during his many scheduled interviews today and during his speech to the nation Tuesday night wherein he will urge for military action against Syria, especially considering how a majority of Americans continue to oppose it, even after the release of those horrific videos of the Syrian victims of the Aug. 21 attack.

]]>by Andrew J. Bacevich

via Tom Dispatch

Sometimes history happens at the moment when no one is looking. On weekends in late August, the president of the United States ought to be playing golf or loafing at Camp David, not making headlines. Yet Barack Obama chose Labor Day weekend [...]]]>

by Andrew J. Bacevich

via Tom Dispatch

Sometimes history happens at the moment when no one is looking. On weekends in late August, the president of the United States ought to be playing golf or loafing at Camp David, not making headlines. Yet Barack Obama chose Labor Day weekend to unveil arguably the most consequential foreign policy shift of his presidency.

In an announcement that surprised virtually everyone, the president told his countrymen and the world that he was putting on hold the much anticipated U.S. attack against Syria. Obama hadn’t, he assured us, changed his mind about the need and justification for punishing the Syrian government for its probable use of chemical weapons against its own citizens. In fact, only days before administration officials had been claiming that, if necessary, the U.S. would “go it alone” in punishing Bashar al-Assad’s regime for its bad behavior. Now, however, Obama announced that, as the chief executive of “the world’s oldest constitutional democracy,” he had decided to seek Congressional authorization before proceeding.

Obama thereby brought to a screeching halt a process extending back over six decades in which successive inhabitants of the Oval Office had arrogated to themselves (or had thrust upon them) ever wider prerogatives in deciding when and against whom the United States should wage war. Here was one point on which every president from Harry Truman to George W. Bush had agreed: on matters related to national security, the authority of the commander-in-chief has no fixed limits. When it comes to keeping the country safe and securing its vital interests, presidents can do pretty much whatever they see fit.

Here, by no means incidentally, lies the ultimate the source of the stature and prestige that defines the imperial presidency and thereby shapes (or distorts) the American political system. Sure, the quarters at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue are classy, but what really endowed the postwar war presidency with its singular aura were the missiles, bombers, and carrier battle groups that responded to the commands of one man alone. What’s the bully pulpit in comparison to having the 82nd Airborne and SEAL Team Six at your beck and call?

Now, in effect, Obama was saying to Congress: I’m keen to launch a war of choice. But first I want you guys to okay it. In politics, where voluntarily forfeiting power is an unnatural act, Obama’s invitation qualifies as beyond unusual. Whatever the calculations behind his move, its effect rates somewhere between unprecedented and positively bizarre — the heir to imperial prerogatives acting, well, decidedly unimperial.

Obama is a constitutional lawyer, of course, and it’s pleasant to imagine that he acted out of due regard for what Article 1, Section 8, of that document plainly states, namely that “the Congress shall have power… to declare war.” Take his explanation at face value and the president’s decision ought to earn plaudits from strict constructionists across the land. The Federalist Society should offer Obama an honorary lifetime membership.

Of course, seasoned political observers, understandably steeped in cynicism,dismissed the president’s professed rationale out of hand and immediately began speculating about his actual motivation. The most popular explanation was this: having painted himself into a corner, Obama was trying to lure members of the legislative branch into joining him there. Rather than a belated conversion experience, the president’s literal reading of the Constitution actually amounted to a sneaky political ruse.

After all, the president had gotten himself into a pickle by declaring back in August 2012 that any use of chemical weapons by the government of Bashar al-Assad would cross a supposedly game-changing “red line.” When the Syrians (apparently) called his bluff, Obama found himself facing uniformly unattractive military options that ranged from the patently risky — joining forces with the militants intent on toppling Assad — to the patently pointless — firing a “shot across the bow” of the Syrian ship of state.

Meanwhile, the broader American public, awakening from its summertime snooze, was demonstrating remarkably little enthusiasm for yet another armed intervention in the Middle East. Making matters worse still, U.S. military leaders and many members of Congress, Republican and Democratic alike, were expressing serious reservations or actual opposition. Press reports evencited leaks by unnamed officials who characterized the intelligence linking Assad to the chemical attacks as no “slam dunk,” a painful reminder of how bogus information had paved the way for the disastrous and unnecessary Iraq War. For the White House, even a hint that Obama in 2013 might be replaying the Bush scenario of 2003 was anathema.

The president also discovered that recruiting allies to join him in this venture was proving a hard sell. It wasn’t just the Arab League’s refusal to give an administration strike against Syria its seal of approval, although that was bad enough. Jordan’s King Abdullah, America’s “closest ally in the Arab world,”publicly announced that he favored talking to Syria rather than bombing it. As for Iraq, that previous beneficiary of American liberation, its government wasrefusing even to allow U.S. forces access to its airspace. Ingrates!

For Obama, the last straw may have come when America’s most reliable (not to say subservient) European partner refused to enlist in yet another crusade to advance the cause of peace, freedom, and human rights in the Middle East. With memories of Tony and George W. apparently eclipsing those of Winston and Franklin, the British Parliament rejected Prime Minister David Cameron’s attempt to position the United Kingdom alongside the United States. Parliament’s vote dashed Obama’s hopes of forging a coalition of two and so investing a war of choice against Syria with at least a modicum of legitimacy.

When it comes to actual military action, only France still entertains the possibility of making common cause with the United States. Yet the number of Americans taking assurance from this prospect approximates the number who know that Bernard-Henri Lévy isn’t a celebrity chef.

John F. Kennedy once remarked that defeat is an orphan. Here was a war bereft of parents even before it had begun.

Whether or Not to Approve the War for the Greater Middle East

Still, whether high-minded constitutional considerations or diabolically clever political machinations motivated the president may matter less than what happens next. Obama lobbed the ball into Congress’s end of the court. What remains to be seen is how the House and the Senate, just now coming back into session, will respond.

At least two possibilities exist, one with implications that could prove profound and the second holding the promise of being vastly entertaining.

On the one hand, Obama has implicitly opened the door for a Great Debate regarding the trajectory of U.S. policy in the Middle East. Although a week or ten days from now the Senate and House of Representatives will likely be voting to approve or reject some version of an Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF), at stake is much more than the question of what to do about Syria. The real issue — Americans should hope that the forthcoming congressional debate makes this explicit — concerns the advisability of continuing to rely on military might as the preferred means of advancing U.S. interests in this part of the world.

Appreciating the actual stakes requires putting the present crisis in a broader context. Herewith an abbreviated history lesson.

Back in 1980, President Jimmy Carter announced that the United States would employ any means necessary to prevent a hostile power from gaining control of the Persian Gulf. In retrospect, it’s clear enough that the promulgation of the so-called Carter Doctrine amounted to a de facto presidential “declaration” of war (even if Carter himself did not consciously intend to commit the United States to perpetual armed conflict in the region). Certainly, what followed was a never-ending sequence of wars and war-like episodes. Although the Congress never formally endorsed Carter’s declaration, it tacitly acceded to all that his commitment subsequently entailed.

Relatively modest in its initial formulation, the Carter Doctrine quickly metastasized. Geographically, it grew far beyond the bounds of the Persian Gulf, eventually encompassing virtually all of the Islamic world. Washington’s own ambitions in the region also soared. Rather than merely preventing a hostile power from achieving dominance in the Gulf, the United States was soon seeking to achieve dominance itself. Dominance — that is, shaping the course of events to Washington’s liking — was said to hold the key to maintaining stability, ensuring access to the world’s most important energy reserves, checking the spread of Islamic radicalism, combating terrorism, fostering Israel’s security, and promoting American values. Through the adroit use of military might, dominance actually seemed plausible. (So at least Washington persuaded itself.)

Relatively modest in its initial formulation, the Carter Doctrine quickly metastasized. Geographically, it grew far beyond the bounds of the Persian Gulf, eventually encompassing virtually all of the Islamic world. Washington’s own ambitions in the region also soared. Rather than merely preventing a hostile power from achieving dominance in the Gulf, the United States was soon seeking to achieve dominance itself. Dominance — that is, shaping the course of events to Washington’s liking — was said to hold the key to maintaining stability, ensuring access to the world’s most important energy reserves, checking the spread of Islamic radicalism, combating terrorism, fostering Israel’s security, and promoting American values. Through the adroit use of military might, dominance actually seemed plausible. (So at least Washington persuaded itself.)

What this meant in practice was the wholesale militarization of U.S. policy toward the Greater Middle East in a period in which Washington’s infatuation with military power was reaching its zenith. As the Cold War wound down, the national security apparatus shifted its focus from defending Germany’s Fulda Gap to projecting military power throughout the Islamic world. In practical terms, this shift found expression in the creation of Central Command (CENTCOM), reconfigured forces, and an eternal round of contingency planning, war plans, and military exercises in the region. To lay the basis for the actual commitment of troops, the Pentagon established military bases, stockpiled material in forward locations, and negotiated transit rights. It also courted and armed proxies. In essence, the Carter Doctrine provided the Pentagon (along with various U.S. intelligence agencies) with a rationale for honing and then exercising new capabilities.