Last week I commented on the unhelpful habit of throwing everything Islamist, no matter how extreme or moderate, into a single conceptual bucket and writing off the whole lot as incorrigible adversaries. That habit entails a gross misunderstanding of events and conflicts in the Middle East, and has the more specific harm of aiding extreme groups at the expense of moderate ones. Shortly afterward Dennis Ross of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy presented a piece titled “Islamists Are Not Our Friends,” which illustrates almost in caricatured form some of the misleading attributes of the single-bucket attitude that I was discussing.

Ross’s article probably is not grounded in Islamophobia, although it partly appeals to such sentiment. The piece ostensibly is about how “a fundamental division between Islamists and non-Islamists” is a “new fault line in the Middle East” that provides “a real opportunity for America” and ought to guide U.S. policy toward the region. In fact it is a contrived effort to draw that line—however squiggly it needs to be—to place what Ross wants us to consider bad guys on one side of the line and good guys on the other side. The reasons for that division do not necessarily have much, if anything, to do with Islamist orientation. Thus anyone who has been unfriendly to Hamas or to its more peaceful ideological confreres in the Muslim Brotherhood are placed on the good side of the line, Iran and those doing business with it are put on the bad side, and so forth.

Ross tries to portray something more orderly by asserting that “what the Islamists all have in common is that they subordinate national identities to an Islamic identity” and that the problem with the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood was that “it was Islamist before it was Egyptian.” What, exactly, does that mean, with particular reference to the short, unhappy presidency of Mohamed Morsi? There were several reasons that presidency was both unhappy and short, but trying to push an Islamist-more-than-Egyptian agenda was not one of them. (And never mind that Ross is risking going places he surely would not want to go by making accusations of religious identification trumping national loyalty on matters relevant to U.S. policy toward the Middle East.) It would make at least as much sense to say that the current president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, was more authoritarian and more in tune with fellow military strongmen than he was Egyptian.

Where Ross’s schema completely breaks down is with some of the biggest and most contorted squiggles in the line he has drawn. He places Saudi Arabia in the “non-Islamist” camp because it has supported el-Sisi in his bashing of the Brotherhood and wasn’t especially supportive of Hamas when Israel was bashing the Gaza Strip. Saudi Arabia—where the head of state has the title Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, the country’s constitution is the Koran, and thieves have their hands amputated—is “non-Islamist”? Remarkable. Conversely, the Assad regime in Syria, which is one of the most secular regimes in the region notwithstanding the sectarian lines of its base of support, is pointedly excluded from Ross’s “non-Islamist” side of the line because of, he says, Syrian dependence on Iran and Hezbollah. Of course, any such alliances refute the whole idea of a “fundamental division” in the region between Islamists and non-Islamists, but Ross does not seem to notice.

Getting past such tendentious classification schemes, we ought to ask whether there is a more valid basis on which we ought to be concerned about states or influential political movements defining themselves in religious terms. If we are to be not merely Islamophobes but true children of the Enlightenment, our concern ought to be with any attempt, regardless of the particular creed involved, to impose the dogma of revealed religion on public affairs, especially in ways that affect the lives and liberties of those with different beliefs.

Such attempts by Christians, as far as the Middle East is concerned, are to be found these days mainly among dispensationalists in America rather in the dwindling and largely marginalized Christian communities in the Middle East itself. In a far more strongly situated community, that of Jewish Israelis, the imposition of religious belief on public affairs in ways that affect the lives and liberties of others is quite apparent. Indeed, the demographic, political, and societal trends during Israel’s 66-year history can be described in large part in terms of an increasingly militant right-wing nationalism in which religious dogma and zealotry have come to play major roles. Self-definition as a Jewish state has been erected as a seemingly all-important basis for relating to Arab neighbors, religion is in effect the basis for different classes of citizenship, and religious zeal is a major driver of the Israeli colonization of conquered territory, which sustains perpetual conflict with, and subjugation of, the Palestinian Arabs.

When religious zealotry involves bloodshed, especially large-scale bloodshed, is when we when ought to be most concerned with its infusion into public affairs. The capacity for zealotry and large-scale application of violence to combine has increased in Israel with the steady increase of religiosity in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and its officer corps. A prominent exemplar of this trend is Colonel Ofer Winter, commander of the IDF’s Gilati Brigade, who has received attention for the heavily religious content of his instructions to his troops. With his brigade poised near the Gaza Strip before the most recent round of destruction there, Winter said in a letter to his troops that he looked forward to a ground invasion so that he could be in the vanguard of a fight against “the terrorist enemy that dares to curse, blaspheme and scorn the God of Israel.” After Winter’s brigade did get to join the fight, he said that a mysterious “cloud” appeared and provided cover for his forces, an event he attributed to divine intervention. Quoting from Deuteronomy, he said, “It really was a fulfillment of the verse ‘For the Lord your God is the one who goes with you to give you victory.’”

Winter’s brigade was involved in what could be described as a culmination of the synthesis of zealotry and bloodshed. When an Israeli soldier was missing and suspected (incorrectly, as it later turned out) to have been captured alive by Hamas in a battle at Rafah, Winter executed the “Hannibal” directive, an Israeli protocol according to which as much violence as necessary is used to avoid having any Israeli become a prisoner, no matter how many civilians or others are killed and no matter that the captured Israeli soldier himself is killed. Over the next several hours a relentless barrage of artillery and airstrikes reduced this area of Rafah to rubble, while Israeli forces surrounded the area so that no one could escape it alive. This one Israeli operation killed 190 Palestinians, including 55 children. There may have been other implementations of the Hannibal directive in the recent Israeli offensive in Gaza; this one is confirmed because Winter himself later spoke openly and proudly about it. Although some secular-minded private citizens in Israel have objected to the heavily religious content of Winter’s leadership, officially there does not appear to be anything but approval for anything he has said or done. He is an exemplar, not a rogue.

In short, an operation officially sanctioned and led in the name of a national god was conducted to slaughter scores of innocents as well as one of the operators’ own countrymen. We ought to think carefully about this incident and about what Colonel Winter represents when we decide how to conceive of fault lines in the Middle East, what it means to insert religion into politics or to be a religious zealot, exactly what it is we fear or ought to fear about religiosity in public affairs, and which players in the Middle East have most in common with, or in conflict with, our own—Enlightment-infused, one hopes—values.

This article was first published by the National Interest and was reprinted here with permission.

]]>“Those who in quarrels interpose, are apt to get a bloody nose.”

—Lord Palmerston on keeping Britain from supporting the South in the American Civil War.

This Wednesday night President Obama will lay out his strategy to “degrade and ultimately defeat” the Islamic State (also known as ISIL/ISIS). [...]]]>

“Those who in quarrels interpose, are apt to get a bloody nose.”

—Lord Palmerston on keeping Britain from supporting the South in the American Civil War.

This Wednesday night President Obama will lay out his strategy to “degrade and ultimately defeat” the Islamic State (also known as ISIL/ISIS). “It is altogether fitting and proper that [he] should do this,” especially because of the nature and possible length of the US commitment that will be involved, the variety of instruments that will need to be employed, the indispensability of American leadership if anything serious is to be done, and the number of countries and organizations whose engagement will be needed. The presentation to the nation is also important to “go over the heads” of Mr. Obama’s opponents in Congress, too many of whom oppose him no matter what he says and does—a mark of the dangerous dysfunction in today’s Washington.

His presentation, however, must not only discuss the ways and means and even the “why”—recent horrific events seem to have answered that last point. It must also offer his vision of the end game or— since this is the Middle East with all of its sharp corners and blind alleys—at least what he is trying to achieve.

US Interests and Values

The most important requirement for analysis is for the president to see the Middle East, first and foremost, in terms of our nation’s interests and as a total package, not just as a set of loosely connected, separate elements. Other countries depend on us to promote their security, and most also want things from us that do not necessarily comport with our own interests. That is not unnatural. Even in the closest of formal alliances—as in NATO or in the bilateral US relationship with Canada—every member of the alliance or coalition will see its situation differently from how others see it, and each will view the overall set of facts through its own independent, national lens.

It would take too long to recite all the factors that define US interests, though most analysts would include the following list:

- Preserving the unimpeded flow of hydrocarbons;

- Ensuring the security of Israel;

- Preventing elements within the region (states, groups, individuals) from exporting terror or taking other hostile actions that affect either us or our allies;

- Promoting the ability of Americans and others to do business and travel safely in the region;

- and seeking an inchoate but still palpable quality called “stability”—or, to break that concept down, emphasizing at least “predictability.”

Along the way we should try to promote human rights and representative governance, which we call “democracy,” though that is not necessarily the same thing, as well as economic and social advances that will promote other objectives, including stability and political modernization.

Having got that out of the way, it is important to reassess some of the elements of what we have been doing that may or not be consistent with these objectives.

Iran’s Role

We have been preoccupied with stopping Iran from getting nuclear weapons, and the negotiations with Iran by the so-called P5+1 nations (US, UK, France, Russia, China and Germany) appear to be close to agreement. But even if the US government decides what is best for us and for keeping Iran from obtaining a “break-out” capability, and even if Iran is prepared to do what is necessary to satisfy US and P5+1 demands, there are countries working to keep the talks from succeeding. Notable among these is Israel, and some of the Persian Gulf Arab states, especially Saudi Arabia, which is at best ambivalent about seeing the negotiations succeed. Israel’s preoccupation with its own security is understandable, and the US is sensitive to Israeli concerns. But the US must make its own judgments; and it should be able to make those judgments without political pressures from Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, or other non-Americans, especially as applied through Congress. The same can be said of both the Israel lobby and the less visible but also potent oil lobby.

For these opponents of an agreement with Iran, the issue is not about just the Iranian nuclear program, but also the geopolitical competitions that are multifarious throughout the Middle East. Keeping Iran from rejoining the international community is a key goal of several Middle Eastern states, but there is no reason for this to be America’s goal, especially since the fire in the Iranian revolution has for some time been burning lower and we need Iranian cooperation in places like Afghanistan (where our two countries worked together in overthrowing the Taliban in 2001), in countering ISIS through tangible actions, in keeping the sea lanes open through the Strait of Hormuz and countering piracy, and potentially in helping to foster a positive future for Iraq. But the US can’t do any of that if its relations with Iran are held hostage by others who not only seek to define the terms of a final nuclear deal, but also prevent Iran from becoming a serious regional power.

“Assad Must Go”

The fall of Middle Eastern dictators in the so-called Arab Spring led (though in the case of Egypt and Libya the aftermath has hardly been positive) to the belief that Syrian President Bashar al-Assad should be next. We continue to talk about “arming moderates,” but no US leader has ever articulated what would come after Assad. There is a basic assumption that, when Assad is gone, all will be rosy. The opposite is more likely true. Added to the ongoing carnage would be the slaughter of the minority Alawites. The risks of a spreading Sunni-Shia civil war would increase dramatically, even more than now. The irony is that many who now worry about ISIS argue that it would not have progressed this far if we had only “armed the moderates” in Syria. But given what would have likely happened if they had succeeded, this argument is nonsense. Yet even now the administration, along with academic and congressional critics, fails to address the consequences of its own rhetoric about getting rid of Assad; that statement has become a mantra, disconnected from any serious process of thought or analysis.

Never-Ending War

Much of what challenges us today derives directly from the misbegotten US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, which we blundered into willy-nilly, with intense support from an unthinking commentariat. Well, these chickens have come home to roost and have caused the hen house to overflow. The US overthrew a minority Sunni government in Iraq that was ruling over the majority Shias and the Kurds. Now, in the eyes of Sunni states, the assault on Assad and the Shia minority in Syria would simply redress the balance.

But no US interests would be served through continued US involvement in a region-wide Sunni-Shia civil war—which is what we’re really talking about here—that we have been involved in, on the Sunni side, for several years, just as we actively sided with Saddam Hussein in his war against Iran in the 1980s.

Sponsors of Terror

Whether we want to admit it or not, much of ISIS’s adherents and what they do derives from actions by putative US friends and allies in the region. Saudi Arabia can argue that the kingdom doesn’t export terrorism, but much of the inspiration and funding for the worst Islamist terrorism comes from Saudi Arabia and some other Gulf Arab states, stemming from the principle of “You can do whatever you want, but just not here at home.” For years, American and other Western troops have died in Afghanistan as a direct result of this “see no evil” policy. The US president needs to make clear that any further inspiration for terrorism, from anywhere in the Middle East, will have consequences. He has yet to do so.

Key Issues

There are many other elements that need to be dealt with in a forthright fashion, within the precincts of the White House if not in public. These include an honest assessment of the importance to the United States of resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and what genuinely needs to be done about it, along with beginning to devise a long-term security strategy and structures for the region as a whole. For now, here’s how the US can start:

- Tell all our friends and allies who are working to prevent Iran from obtaining a bomb-making capacity that we share that interest, but that we—who in the final analysis provide for their security—will determine what is best in the negotiations with Iran, and they should back-off in their efforts to prevent success;

- Understand and accept that we do have some compatible interests with Iran, beginning in Afghanistan and against ISIS, and we will not let these interests be held hostage to the desires of other Middle East states who want to keep Iran isolated for their own geopolitical reasons;

- Persuade our European allies to understand that they, too, have “a dog in this fight” and cannot be as half-hearted in support of Mr. Obama’s “degrade and ultimately defeat” strategy against ISIS as most of them were at last week’s NATO summit in Wales;

- Review our analysis of the situation in Syria and understand that we cannot continue to call for “Assad to go” without having some sense of what would happen next, what it would mean to us, and the cost to the United States of having to sort the matter out. In practice, that means that, at least for now, Assad is better than the likely alternatives;

- Make clear that anyone in the Middle East who supports or tolerates terrorism, directly or indirectly, will pay a heavy price with us;

- Put all the Sunni states on notice that we will not do their business for them in righting the balance with the Shia or in supporting their geopolitical ambitions that are not also consonant with US national interests (the same goes with Israel);

- And, above all, serve notice that we will not continue to be a party to any of the civil wars taking place in the region.

Maybe it is already too late to get this right, in America’s interests. But President Obama can start by “getting up on his hind legs” and showing some anger—as he has been doing of late. He can finally gather around him people of experience who both understand the Middle East and the craft of strategy. And he can insist that the US put its own interests first and stop letting itself be a cat’s paw for anyone else.

There is thinking and acting to do, if, following Palmerston’s injunction, we are to avoid making worse the bloody nose we have already suffered by allowing ourselves to become part of the Middle East’s civil wars.

]]>by Wayne White

American political and media commentary on ISIS (which calls itself the Islamic State) since the beheading of James Foley has been flush with exaggeration and skewed focus. Identifying Foley’s murderer is desirable but far less important than tackling ISIS proper and its leadership. Unfortunately, many ISIS cadres have done [...]]]>

by Wayne White

American political and media commentary on ISIS (which calls itself the Islamic State) since the beheading of James Foley has been flush with exaggeration and skewed focus. Identifying Foley’s murderer is desirable but far less important than tackling ISIS proper and its leadership. Unfortunately, many ISIS cadres have done far worse off camera. The voice narrating the video of Foley’s execution was British, and he was probably chosen by ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi simply to produce maximum shock effect in the West.

Most importantly, ISIS faces numerous challenges in holding onto what it has now, particularly in Iraq, where further expansion will likely be marginal. There are also ISIS vulnerabilities to be exploited by a new Iraqi government with much broader appeal. ISIS clearly poses a threat to the US (and other countries), but that threat needs to be soberly assessed.

Dialing Down the Hysteria

The beheading of Foley, a dreadful and tragic event, sparked a surge of gloom, doom, and hype among senior US officials and within the media at large. Of late, estimates of total ISIS fighters and foreign recruits have soared, but are based on what could only be iffy information. This is precisely what ISIS’s leaders intended.

ISIS perceives, as do other ruthless entities, that the US (and its allies) are traumatized far more by the death of one citizen than vastly broader atrocities in the Middle East. Hurt by US airstrikes (and fearing more) ISIS hoped to frighten Americans enough to make Washington back off. In that sense, the execution boomeranged: US and Western leaders are more alarmed, but determined to ramp up, not relax, measures against the radical Sunni group.

ISIS is dangerous, but its nature and the threat it represents must be defined accurately. A bizarre characterization of ISIS was made by Joint Chiefs Chairman General Martin Dempsey last week when he said ISIS has an “apocalyptic, end of days strategic vision.” This concept relates more closely to the Biblical New Testament Book of Revelation, reflecting mostly Christian, not Islamic, thinking. In fact, ISIS’s strategic vision, in historical terms, is rather pedestrian, albeit infused with barbarism: a quest to establish its version of a state, reinforce its power, defend or expand its present conquests, and lash out at its enemies.

Territorially, ISIS is weaker than suggested by the lurid maps showcased regularly by the media. Over 90% of the land under ISIS control is the driest, most underpopulated, and poorest in the greater Fertile Crescent region. In that respect, some of its holdings in Iraq are its most valuable assets, including large intact cities along rivers.

Vulnerabilities

The militant al-Nusra Front (less abusive than ISIS, and clashing with it in Syria) is well aware of ISIS’s vulnerability to foreign military action. It is no coincidence that al-Nusra released American hostage Peter Theo Curtis only days after Foley’s murder. Al-Nusra evidently is afraid of a harsh US response against ISIS, and hopes to keep out of the line of fire.

Despite the extent of its success, ISIS does not have a very large army of dedicated fighters. Its fanaticism and its use of shock, awe, and terror have been force multipliers. However, spread thin along the edges of its sprawling realm, it recognizes increased American aerial attacks in support of better-equipped Kurdish and revitalized Iraqi Army units could threaten areas far beyond just the Mosul Dam.

The heavy weapons ISIS secured while seizing Mosul and has since used to its advantage are largely irreplaceable, and continuing US air attacks would erode that edge quite a lot. At some point, ISIS could be reduced to fighting much as it did before—as light infantry.

Furthermore, having generated a more intense foreign and Iraqi domestic reaction, if faced with stiffer opposition simultaneously in both Syria and Iraq, ISIS would have to juggle its limited forces among various threatened sectors (always dicey). ISIS has also been fighting behind its own lines against surrounded Iraqi garrisons in one city, a major dam, Iraq’s largest refinery, several towns, and some areas dominated by hostile Sunni Arab tribes.

Many non-extremist ISIS Iraqi allies are potentially unreliable. However, ISIS does not have enough core combatants to fully occupy its vast holdings, so it depends heavily upon these allies.

As with its al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) predecessor, the restrictions and abuses committed by ISIS will eventually alienate many localities, secular Sunni Arab factions, and tribes. To keep tribes, Ba’athists, and former insurgents who do not share its fanatical vision loyal, ISIS might have to spread around some of its money.

Yet, in the face of airstrikes and warnings of worse from the Jordanians, Saudis and others close to former Sunni Arab Iraqi military officers and certain tribes, these fellow travelers could get very nervous about their future with ISIS. And with their prior nemesis in Baghdad, Nouri al-Maliki, gone, cutting a deal with a new government while decent terms can still be achieved could begin to look very inviting.

A New and Improved Iraqi Government?

To encourage the desertion of ISIS’s allies, prime minister-designate Haider al-Abadi must put together a new government tailored to–despite Baghdad’s political snake pit–reduce the Sunni Arab grievances upon which ISIS thrives. Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, a source of emulation for nearly all Iraqi Shi’a, knows this.

He appealed at prayers on Aug. 22 for a government made up of leaders who care about Iraq’s “future and its citizens,” regardless of their ethnic and religious affiliations, in a “realistic” fashion. Sistani’s pressure on Iraq’s dominant Shi’a majority politicians already made the difference in ousting Maliki. Hopefully, Sistani will keep the heat on until such a government is formed.

If many of ISIS’s allies are not wooed away, even a considerably revitalized Iraqi Army and Peshmerga supported by airstrikes might make only slow, costly progress against ISIS forces. In cities like Mosul, Fallujah, Ramadi, and others, ISIS could be near impossible to oust short of inflicting severe damage on these large urban areas. This is what happened across Syria in fighting between the regime and various rebels.

In 2004, from my perch in the US Intelligence Community, I warned of the destruction that would result from an American assault on insurgent-dominated Fallujah. Sure enough, despite the employment of crack US forces on the ground and far more careful use of firepower than by the Assad regime in Syria, the US operation heavily damaged the majority of the city. Some of the residual bitterness over that carnage still fuels militancy there—ISIS’s first unchallengeable conquest in Iraq.

Overseas Threat

Ironically, the danger of ISIS attacks radiating outward from its Syrian-Iraqi base would become more significant if ISIS suffered major reverses in the field. If the self-declared “Caliphate” was in retreat and its area of control shrinking, recruits flush with rage and possessing foreign passports would be more likely to leave intent on revenge.

There is, however, a more proximate threat. With numerous individuals inspired by ISIS’s twisted attitudes probably still at home, terrorist attacks could occur even if Western passport holders fighting with ISIS never return. Some of these domestic “sleepers” could attack soft targets at any time in response to calls from ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi—or as individuals.

So is ISIS a direct threat to the US? Yes. However, the same can be said of a number of al-Qaeda-affiliated groups. Instead of obsessing over that definition or chasing down one killer, all concerned must focus on how that overarching threat could manifest itself both domestically and regionally.

]]>by Jim Lobe

Earlier today the Office of the Prime Minister of Israel tweeted a visual message comparing ISIS (the Islamic State) to Hamas with an accompanying screenshot from the video of American photojournalist James Foley’s gruesome execution. The PM’s office encouraged Twitter users to share the tweet with others, a call that was taken [...]]]>

by Jim Lobe

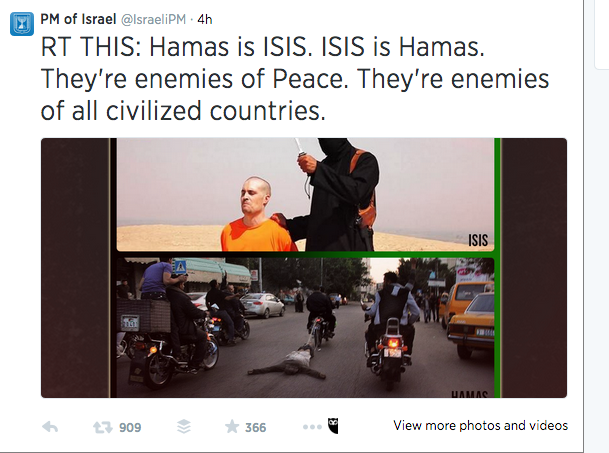

Earlier today the Office of the Prime Minister of Israel tweeted a visual message comparing ISIS (the Islamic State) to Hamas with an accompanying screenshot from the video of American photojournalist James Foley’s gruesome execution. The PM’s office encouraged Twitter users to share the tweet with others, a call that was taken up by Benjamin Netanyahu’s official Twitter account, along with more than 900 others. It has since been removed, possibly due to outrage over the PM’s use of the murder of an innocent photojournalist, which happened just two days earlier, for political gain. But the Israeli government is continuing its campaign of likening Hamas to the Islamic State.

Putting aside the astonishing tastelessness of the now-removed collage released by Netanyahu, not to mention the blatantly cynical attempt to equate ISIS with Hamas, is Bibi suggesting that Obama should follow his example in dealing with ISIS by, for instance, trading up to 1,000 ISIS militants who it may capture for one US citizen, as Netanyahu himself did with Hamas in 2011?

]]>by Wayne White

Coverage of the Iraqi crisis from the media to Capitol Hill has been characterized by scary worst-case scenarios and exaggerations of the military capabilities of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Yet this Islamic extremist group has probably already seized most of the important Iraqi real estate it [...]]]>

by Wayne White

Coverage of the Iraqi crisis from the media to Capitol Hill has been characterized by scary worst-case scenarios and exaggerations of the military capabilities of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Yet this Islamic extremist group has probably already seized most of the important Iraqi real estate it is going to get. It is vital for the US to avoid simply doing Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki’s sectarian dirty work for him and returning Iraq to its previously miserably unbalanced status quo. Under the circumstances, however, avoiding that misstep poses daunting challenges.

The successes of ISIS in Iraq do represent a dicey problem for Iraqi authorities in Baghdad and the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) in the north. ISIS now commands the majority of Iraq’s Sunni Arab heartland as well as a large swathe of mixed ethno-sectarian areas, albeit those with substantial Sunni Arab populations. However, very little territory remains outside ISIS’ current holdings where a Sunni Arab extremist movement would be received with open arms or even passive resignation.

Collapse of dysfunctional army units

Admittedly, the performance of Iraqi Army units assigned to Sunni Arab areas like Mosul has been dismal. Retreating in the face of a few thousand lightly armed militants largely without a fight would have been bad enough. However, the loss of all cohesion, mass desertion, and the abandonment of valuable armaments, ammunition, and equipment compounded the collapse and gave additional advantages to ISIS.

These events revealed just how badly crippling internal problems have undermined the Iraqi Army. This has been especially so since Iraq’s dominant Shia establishment made it effectively impossible for American military advisors and trainers to remain in Iraq beyond the US withdrawal in 2011.

Throughout the ranks, the army has suffered from a high degree of politicized, sectarian, or bribe-generated appointments and promotions, debilitating corruption, and a severe lack of intelligence concerning Sunni Arab areas of the country. Its political favoritism and corruption appear to exceed what prevailed during the Saddam Hussein era. The units that collapsed apparently had no clue ISIS was about to attack Mosul. There have also been suggestions that self-serving unit commanders were more concerned about their personal safety than rallying their troops.

Tamping down the panic

As I noted on June 11, Maliki and his cronies woefully underestimated Sunni Arab tolerance for and potential pushback against years of exclusion and abuse. Now, however, a stunned and reeling Iraqi government probably is overestimating ISIS. Correspondingly, in the wake of its run of unexpectedly easy successes, ISIS might well be returning the favor by underestimating Iraqi Army units and militias in Baghdad.

In any upcoming fighting in Baghdad and the south, ISIS would be far more vastly outnumbered than it was in Mosul and likely to encounter armed Shia elements mustering quite a bit of fanaticism of their own. Only one portion of the army was routed in the north; a city many times the size of Mosul would be a huge mouthful for so small a force of ISIS fighters; and Iranian combatants could very well join the fight.

Moreover, despite Senator Lindsey Graham’s comment yesterday that the US “should have discussions with Iran” about the Iraq crisis, this may be irrelevant. Whether talks occur or not, Tehran, already closely aligned with the present Iraqi government, will likely act as it sees fit in Iraq to serve Iranian interests — regardless of US views on the matter.

Finally, if, as expected, the US commences air strikes, ISIS’ task of moving farther south would be that much more daunting. Near the top of the target list of those anticipated US air (and drone) strikes should be major pieces of military equipment seized by ISIS in the north. That would prevent ISIS from deploying them over the border into Syria (already in progress) or putting them to use in its upcoming clashes with Iraqi government forces.

Homeland imperiled by ISIS gains?

Those harping on ISIS’ “threat to the Homeland” are exaggerating that aspect of the problem. Since adopting the ISIS moniker in April 2013, and during operations by its antecedents since January 2012 in Syria (and going back 10 years in Iraq), ISIS has posed little threat to US interests outside Syria and Iraq.

Of late, its efforts have been consumed by its struggle to overthrow the Assad regime in Syria, combat moderate and other Islamist rebel rivals in Syria, and recently moving against the Iraqi government. There is a threat to the US to consider, but that is likely to emerge further down the line (but, ironically, could be heightened by US air strikes against ISIS in defense of Maliki & Co.)

One potential direct threat to the US that has also existed as part of the Syrian rebellion since 2012 is that of numerous US and other Western European citizens fighting with ISIS and the extremist al-Nusra Front. The prospect of those militants entering the US at some point (US visa requirements are typically waived for Western Europeans) does pose a threat. That threat is magnified by the difficulty Western intelligence and law enforcement agencies have had in gathering precise data on the identities of such individuals.

Trying to harness the Maliki government

Extracting substantial change in the Iraqi government’s abusive behavior toward its Sunni Arab community poses an extremely tough challenge for US policymakers. Holding back US air and other military support to secure this agreement could render getting assurances the easiest part of this endeavor.

If substantial portions of Sunni Arab Iraq were recovered from ISIS, it is difficult to envision how Iraqi government compliance with a more tolerant policy could be monitored reliably. And accountability is critical; Maliki has broken such pledges before. In fact, it would be best all-round if Maliki could be dumped as prime minister in the ongoing negotiations to form Iraq’s post-election government, but there are no indications that his Shia backers would cooperate.

Further complicating this crucial issue, the upcoming mainly sectarian face-off will inevitably result in atrocities on both sides. Already, ISIS has claimed and videoed its execution of large numbers of captured Iraqi soldiers, inflaming the atmosphere. The recruitment of Shia volunteers (with many hardened Shia militiamen undoubtedly among them) along with the possible employment of elite Quds Force cadres from Iran has also been reducing Baghdad’s control over the behavior of its own combatants.

Atrocities will undermine the ability of even a well-intentioned government in fielding a policy of communal toleration. Even worse, instead of a fast-paced government campaign to drive ISIS out of most of its Iraqi holdings, portions of the coming fight might resemble the more prolonged and grueling 2003-08 US-Iraqi struggle against the Sunni Arab insurgency and ruthless Shia militias.

Sorting out a workable way to thread this complex needle toward a new Iraqi national sectarian compact should be as high a priority for the Obama administration as military measures meant to defeat ISIS. The international community could perhaps be drawn into the task of monitoring Baghdad’s compliance in the coming years. Still, preventing a return to pre-crisis sectarian hostility is likely to be as difficult as the immediate military task of containing and rolling back ISIS — if not more.

This article was first published by LobeLog and was reprinted here with permission.

Photo: Carry weapons and waving Iraqi flags, volunteers join the Iraqi army to fight militants from the radical Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in eastern Baghdad June 15, 2014.

]]>by Mark N. Katz

The radical jihadist group, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIL or ISIS), has seized much of Iraq’s Sunni Arab heartland and reached the outskirts of Baghdad. The armed forces of Iraq’s US-backed, Shia majority elected dictatorship have not only failed to prevent this, but are also [...]]]>

by Mark N. Katz

The radical jihadist group, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIL or ISIS), has seized much of Iraq’s Sunni Arab heartland and reached the outskirts of Baghdad. The armed forces of Iraq’s US-backed, Shia majority elected dictatorship have not only failed to prevent this, but are also fleeing as ISIS advances.

There is a real possibility that the government of Nouri al-Maliki will fall, and that ISIS will be able to reassert Sunni Arab minority rule over Iraq, which existed under Saddam Hussein and well before him. An ISIS in charge of Iraq will also be able to aid its beleaguered compatriots in Syria fighting the Assad regime, as well as help Sunni jihadists in other neighboring countries such as Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and perhaps even Iran (where there is indeed a large Sunni population believed to be highly disaffected from Tehran’s Shia rulers).

What is currently happening in Iraq does not serve the interests of America, its Western and Arab allies, or anyone except the jihadists. The Obama administration, however, is not going to re-intervene in Iraq now after only recently ending the long, costly, and inconclusive US-led intervention there, as well as winding down a similar one in Afghanistan. Congress and the American public are unlikely to support intervention anyway, as the widespread US domestic opposition to Obama’s 2013 request for congressional approval for a much more limited strike on Syria demonstrated.

Can anything, then, be done to stop ISIS from seizing more of Iraq, including Baghdad? Or, under the current circumstances, is that simply inevitable?

Nothing is inevitable. The rise of ISIS so far has less to do with its strength than with the weakness of its main adversary, the Maliki government. Right now, ISIS’s “control” is quite tenuous. Indeed, ISIS might be just as surprised as everyone else that the collapse of the Maliki government has created a vacuum allowing it to move in. Still, ISIS’ newfound gains also mean that its forces are likely stretched thin — and thus vulnerable — at present.

There are accordingly policy options for halting the spread of ISIS and even rolling it back that exist between US intervention on the one hand and doing nothing on the other. One of the most important of these arises from the fact that ISIS is not only opposed by the U.S., but also by neighboring states and important groups inside Iraq. Indeed, the rise of ISIS threatens these local and regional actors far more than it does the U.S., thus giving Washington opportunities to support those who are strongly motivated to resist this jihadist militia. These include:

The Kurds: While the Maliki government’s forces have fled from ISIS, the Kurdish Regional Authority has made clear that it intends to resist and has already seized control of the divided northern city of Kirkuk.

Shia Arabs: The Maliki government’s impotence notwithstanding, the Iraqi Arab Shia majority has a very strong incentive to oppose ISIS’ efforts to re-impose a Sunni minority regime upon them.

Anti-Jihadist Sunni Arabs: While Sunni Arabs initially resisted the American-led military intervention and supported ISIS’ predecessor, al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI), many Sunni Arab tribesmen later allied with the U.S. against AQI since it was increasingly attacking them. These Sunni tribes, whom Maliki alienated when America withdrew, have not forgotten how al-Qaeda treated them — and ISIS has not forgotten how these tribes fought with the Americans.

Iran: Despite the many differences between Washington and Tehran, one common interest (that is seldom recognized publicly) is that both fear the rise of radical Sunni jihadist movements, including ISIS.

Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Jordan: Despite their fears of Iran and their support for the opposition to Tehran’s ally, the Assad regime, these Sunni Arab monarchies in particular have strong reason to fear that the rise of jihadist forces in Iraq will threaten them sooner or later (indeed, this will probably happen sooner rather than later).

There are, then, plenty of local and regional actors that are strongly motivated to resist the rise of ISIS that the US and others can either actively or (in Iran’s case) passively support. The problem, of course, is that these actors often distrust each other and act at cross-purposes. An American diplomatic initiative, though, could help minimize these differences.

Essentially, what everyone needs to understand is that Iraq is simply too fractious to be successfully ruled by a strong central government. Instead, it can either exist as a federation, in which each of its three main communities has autonomy within the area of the country where it is the majority, or co-exist as three de facto, or even de jure, independent states. And, even if the borders between these three regions cannot be completely agreed upon, the areas of disagreement can be minimized and arrangements made to accommodate contested mixed areas in particular.

Those who object to cooperation with Iran on the basis that they are anti-American should be reminded that despite their differences, the US and Iran were able to cooperate to some extent against the Taliban in the early stages of the US-led intervention in Afghanistan, and that Iran gave more support to the US-backed Maliki government than any of Washington’s Sunni Arab allies. We have already proved, in other words, that we can cooperate pragmatically when our interests are at stake.

Those who object to cooperation with Saudi Arabia on the basis that it supported al-Qaeda elements in the past should be reminded that after al-Qaeda began launching attacks inside the kingdom in 2003, Riyadh well understood that Sunni jihadists will attack it when the opportunity arises.

Finally, those who object to cooperation with the Kurds on the basis that Turkey, among others, will object should be reminded that Turkey and the Kurdish Regional Authority in Northern Iraq have established a remarkable degree of economic cooperation, that Turkey has its own internal Sunni jihadist problem, and that a strong Kurdish government in Northern Iraq helps protect Turkey from ISIS or similar groups, which would probably attack Turkey from Iraq if they could.

ISIS will not prevail because it has suddenly grown much stronger. ISIS can prevail, though, if those who could work with one another to stop it fail to do so.

Photo: A screenshot from a video purportedly showing an execution of a man by ISIS.

This article was first published by LobeLog. Follow LobeLog on Twitter and like us on Facebook

]]>