by Derek Davison

A former senior analyst for Mossad, Yossi Alpher, told an audience in Washington Thursday that Israel sees the Islamic State (ISIS or IS) as an “urgent” national security concern, but the context of his talk at the Wilson Center implied that the extremist Sunni group does not top any Israeli list of threats. In fact, Alpher seemed to suggest at times that the actions of IS, particularly in Iraq, may ultimately benefit Israel’s regional posture, particularly with respect to Iran. He also called the American decision to intervene against IS “perplexing.”

Iran, unsurprisingly, topped Alpher’s list of “urgent” Israeli security threats, but he downplayed the prospect of a nuclear deal being struck by the Nov. 24 deadline for the negotiations and focused instead on the “hegemonic threat” Iran allegedly poses. Indeed, the former director of Israel’s Institute for National Security Studies was mainly concerned with an Iran strengthened by close alliances with Iraq and Syria as well as Hezbollah in Lebanon and now potentially expanding its reach into Yemen, whose Houthi rebels have made major military gains in recent weeks.

Alpher identified the threat of extremist/terrorist organizations as Israel’s second-most urgent threat, but within that category he placed Hamas and Hezbollah ahead of IS. He allowed that IS “threatens to reach very close” to Israel, particularly if it manages to make inroads in Jordan, where polls indicate that a significant minority of the population does not see IS as a terrorist group, and where there has been vocal opposition to King Abdullah’s support for the US-led anti-IS coalition. Indeed, Alpher suggested that Israel should try to defuse current tensions over the Temple Mount, which have caused Abdullah to suffer politically at home, in order to forestall an increase of IS sympathy within Jordan.

Several of Alpher’s later remarks seemed to suggest that the activities of IS in Syria (at least those that have targeted Syrian President Bashar al-Assad) and in Iraq may actually pay dividends for Israel. If the primary threat to Israel’s security is, as Alpher claims, Iran, and not just Iran’s nuclear program but also its regional hegemonic aspirations, then any movement that opposes Assad—a long-time Iranian ally—and that threatens the stability and unity of Iraq—whose predominantly Shia government has also developed close ties with Tehran—is actually doing Israel a service. It apparently doesn’t matter if that group might also someday pose a threat to Israel. It’s in this context that Alpher described America’s decision to intervene against IS as “perplexing.” He questioned the US commitment to keeping Iraq whole, noting that an independent Kurdistan would be “better for Israel,” and said that, as far as Syria’s civil war is concerned, “decentralization and ongoing warfare make more sense for Israel than a strong, Iran-backed Syria.”

The tone of Alpher’s remarks on IS echoed a number of recent comments from top Israeli government and military figures. Earlier this month, the IDF’s chief of staff, Lt. General Benny Gantz, told the Jerusalem Post that “the IDF has the wherewithal to defend itself against Islamic State,” and then went on to describe Hezbollah as Israel’s most immediate security concern. Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Ya’alon also told PBS’s Charlie Rose on Sunday that Israel is contributing intelligence to the anti-IS coalition, but suggested that it was doing so because it has “a very good relationship with many parties who participate in the coalition,” not because it perceives IS as a near-term threat to Israel. Finally, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s speech to the UN General Assembly on Sept. 29 made several references to IS, but only as a secondary threat to Iran’s alleged nuclear weapons program or in conflating IS with Hamas and, really, every other Islamic extremist group in the world.

Alpher made pointed criticisms of the US-led effort against IS in an exchange with Wilson Center president and former House member, Jane Harman, who pushed back against his characterization of US “mistakes” in the region. He was particularly critical of the Obama administration’s handling of Egypt, arguing that it “made things worse” by failing to support the Mubarak regime in 2011 and trying instead to “embrace” the democratically elected (and now imprisoned) Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohamed Morsi, and then by failing to welcome the military coup that eventually put current President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in office.

Harman questioned whether a stronger show of American support for the increasingly authoritarian direction of Egypt’s politics would hinder any effort to counter the anti-Western narrative upon which much of IS’ support and recruitment is based. Alpher’s answer, and indeed a recurring theme in his remarks, was that the question of narratives and terrorist recruitment is irrelevant to an Israeli security framework that is focused only on the most immediate threats (or, as he put it, “on what will bring short-term stability”).

The emphasis on the short-term is one of the defining features of Netanyahu’s term in office, particularly in his dealings with the Palestinians, but also in Israel’s broader security posture, and it may well cause greater problems for Israel in the long-term.

]]>Once upon a time, it seemed that the Obama administration had held off opponents in Congress as well as pressure from Israel in order to press forward with negotiations with Iran. It seemed that President Barack Obama’s penchant for diplomacy was finally bearing fruit and that the United States and Iran were coming to the table with a sense of determination and an understanding that a compromise needed to be reached over Iran’s nuclear program.

These days, the story is different. Almost halfway through the four-month extension period the parties agreed to in July, the possibility of failure is more prominently on people’s minds, despite the fact that significant progress has been made in the talks. Right now, both sides have dug in their heels over the question of Iran’s nuclear enrichment capabilities. Iran wants sufficient latitude to build and power more nuclear reactors on their own, while the United States wants a much more restrictive regime.

Part of the calculus on each side is the cost to the other of the failure of talks. Iran is certainly aware that, along with escalating tensions with Russia, the U.S. is heading into what is sure to be a drawn-out conflict with the Islamic State (IS). The U.S. and its partners would clearly prefer to avoid a new crisis with the Islamic Republic, especially when the they need to work with Iran on battling IS forces, however independently and/or covertly they may do it.

The U.S. certainly recognizes that Iranian President Hassan Rouhani staked a good deal of his political life on eliminating the sanctions that have been crippling the Iranian economy. But both sides would be wise to avoid a game of chicken here, where they are gambling that the other side will ultimately be forced to blink first.

On the U.S. side, there are many in Washington who would not be satisfied with anything less than a total Iranian surrender, something the Obama administration is not seeking. Those forces are present in both parties, and, indeed, even if Democrats hold the Senate and win the White House in 2016, those voices are likely to become more prominent as time goes on.

But many believe that on the Iranian side, this is a life-or-death issue politically for the reform-minded Rouhani, and that may not be the case. It is certainly true that conservative forces in Iran, which had been ascendant under President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, are lying in wait to pounce on Rouhani if he doesn’t manage to work out a deal that removes U.S.-led sanctions against Iran. It is also true that Rouhani deals with a Supreme Leader who is highly skeptical not only of Washington’s sincerity, but of the kind program Rouhani’s reform-minded allies wish to pursue on the domestic front. Rouhani’s support derives most reliably from an Iranian public fed up with the failure of the conservatives to improve their lives. He dare not disappoint them.

But if Washington policy-makers believe that this amounts to a political gun to Rouhani’s head, they are mistaken. In a just-released paper published by the Wilson Center. Farideh Farhi, the widely quoted Iran expert at the University of Hawaii Manoa (and LobeLog contributor), points out that Rouhani does have options if the negotiations fall apart.

“To be sure, Rouhani will be weakened, in similar ways presidents in other countries with contested political terrains suffer when unable to deliver on key promised policies,” according to Farhi.

But he will continue to be president for at least another three, if not seven, years. The hardliners will still not have their men at the helm of the executive branch and key cabinet ministries. Given their limited political base for electoral purposes, they will still have to find a way to organize and form coalitions to face a determined alliance of centrists, reformists, and moderate conservatives—the same alliance that helped bring Rouhani to power—in the parliamentary election slotted for early 2016. And, most importantly, Rouhani will still have the vast resources of the Iranian state at his disposal to make economic and social policy and will work with allies to make sure that the next parliament will be more approving of his policies.

Farhi’s point is important. Rouhani has options and he need not accept a deal that can be easily depicted by conservatives as surrendering Iran’s independent nuclear program. As pointed out in a recent survey of Iranian public opinion we covered earlier in the week, this issue is particularly fraught in Iran. It has been a point of national pride that Iran has refused to bend to Western diktats on its nuclear program, diktats that are seen as hypocritical and biased by most Iranians. That estimate is not an unfair one, given previous demands by the U.S. (and one still insisted upon by Israel and its U.S. supporters) that Iran forgo all uranium enrichment. Such a position would force Iran to depend on the goodwill and cooperation of other countries — Russia, in the first instance — whose reliability in fulfilling commitments may depend on how they perceive their national interest at any given moment. Other countries are not held to such a standard, a source of considerable resentment across the Iranian political spectrum.

Rouhani has wisely chosen not to challenge the public on this point, but rather commit himself to finding an agreement that would end sanctions while maintaining Iran’s nuclear independence, albeit under a strict international inspection regime. This is far from an impossible dream. The Arms Control Association published a policy brief last month with a very reasonable outline for how just such a plan which would satisfy the needs of both Iran and the P5+1.

In principle, both sides could live with such an outcome if they can put domestic politics aside. But of course, they cannot.

Still, the consequences of failure must not be ignored. With Barack Obama heading into his final two years as President, it is quite possible, if not probable, that his successor — regardless of party affiliation — will be much less favorable toward a deal with Iran. In that case, we go back to Israeli pressure for a direct confrontation between the United States and Iran and escalating tensions as Iran feels more and more besieged by the Washington and its western allies.

Rouhani, for his part, may be able to continue his path of reform and re-engagement with the West, but the failure of these talks would be an unwelcome obstacle, according to Farhi.

Rouhani and his nuclear team have had sufficient domestic support to conduct serious negotiations within the frame of P5+1. But as the nuclear negotiations have made clear, the tortured history of U.S.-Iran relations as well as the history of progress in Iran’s nuclear program itself will not allow the acceptance of just any deal. Failure of talks will kill neither Rouhani’s presidency nor the ‘moderation and prudence’ path he has promised. But it will make his path much more difficult to navigate.

All of this seems to amount to sufficient incentive for the two sides to bring themselves toward the reasonable compromise that both can surely envision. At least, one hopes so.

]]>by Derek Davison

Most of the recent discouraging news about the talks between Iran and world powers has focused on the substantial disagreement regarding Iran’s uranium enrichment capacity. The two sides differ sharply on how much enrichment capacity Iran requires, how much it should be allowed to maintain once [...]]]>

by Derek Davison

Most of the recent discouraging news about the talks between Iran and world powers has focused on the substantial disagreement regarding Iran’s uranium enrichment capacity. The two sides differ sharply on how much enrichment capacity Iran requires, how much it should be allowed to maintain once a comprehensive agreement is reached, and how quickly it should be allowed to expand that capacity over the agreement’s timeframe (the length of which is itself another contentious point).

However, while this dispute could sink the chances of reaching an agreement on its own, the focus on enrichment masks another and perhaps equally volatile issue: the process through which Iran will receive sanctions relief if a deal is reached. This question not only factors into the terms of any comprehensive accord, but also carries enough uncertainty to potentially cause any final deal to break down in the future if expectations on either side are violated. This issue was the focus of a July 8 panel discussion at the US Institute for Peace (USIP), “Iran Sanctions: What the US Cedes in a Nuclear Deal,” moderated by the USIP’s Robin Wright and including Suzanne Maloney of the Brookings Institution, Kenneth Katzman of the Congressional Research Service, and Elizabeth Rosenberg of the Center for a New American Security.

The duration of a final deal is, as Maloney pointed out, a “sleeper issue” in the negotiations, which are quickly approaching the July 20 deadline. Negotiators from the P5+1 (the US, UK, France, China, and Russia plus Germany) want to maximize the length of time that Iran’s nuclear program will remain under international monitoring while delaying sanctions relief for as long as possible. Iran, understandably, wants considerable immediate sanctions relief and a minimum duration final deal. The two sides will surely compromise on a deal that lifts sanctions progressively, with relief tied to specific Iranian activity under the terms of the accord. But the devil is always in the details, and working out the specific timetable for sanctions relief and the steps to which it will be pegged is certainly among the more difficult challenges the negotiators are facing in Vienna. This process is made all the more complicated by the fact that the US has been imposing sanctions on Iran since its 1979 Islamic Revolution, for reasons that have had nothing to do with Iran’s nuclear program. For example, Iran’s support for the militant Lebanese group Hezbollah was used as the justification for some of the earliest and strongest US sanctions against Iranian banks, and those sanctions are unlikely to be altered if a final deal is reached.

The issues of uncertainty and misunderstandings regarding sanctions relief, and the potential for this to threaten the stability of a final deal, were widely discussed by the panelists. Iran wants, and President Hassan Rouhani needs, substantial sanctions relief to boost an economy that continues to suffer from high inflation and high unemployment as well as economic sanctions. In a practical sense, as Katzman noted, the initial round of sanctions relief will have to be fairly sizable; there is no benefit to Iran if, for example, the deal lifts caps on Iran’s oil exports without also allowing Iranian companies and banks to properly access the international banking system. In a strictly legal sense, American sanctions against Iran could be quickly suspended via executive waiver, which must be renewed every six months but does not require Congressional approval in the way that a permanent lifting of sanctions would.

However, the actual speed with which companies would do business with Iran will likely be slowed by a number of complicating factors. These include concerns over the sustainability of the agreement, the stability of the Iranian regime, and the ability of Rouhani’s administration to reduce corruption, according to Rosenberg. But the primary complication will undoubtedly be uncertainty over the precise nature of the sanctions relief and the different sanctions regimes that countries, chiefly the US, will continue to levy against Iran. Rosenberg noted that there will be a period in the wake of a final deal in which companies will need to figure out the limits of sanctions relief to Iran, particularly navigating the differences between European and US law.

It may prove difficult or impossible to separate American sanctions that were put in place specifically as a result of Iran’s nuclear activity, which would be dealt with under the terms of a comprehensive accord, from those related to other issues like Iran’s support for Hezbollah, which would be untouched by such a deal. Iranian negotiators will likely be satisfied with a deal that allows European firms (especially banks) to do business in Iran again, but if those firms are still wary of other remaining sanctions, they will remain reluctant to pursue opportunities in Iran. In practical terms, then, sanctions relief will be a slow process. For an Iranian public that, as Wright pointed out, expects a deal and wants benefits quickly, such a delay could damage both US credibility and the Rouhani presidency, and could even collapse the overall framework of a final deal.

]]>by Derek Davison

The three key timelines at the center of the negotiations between world powers and Iran over its nuclear program were the subject of a panel discussion at the Wilson Center today. Jon Wolfsthal of the Center for Nonproliferation Studies spoke about the duration of a hypothetical comprehensive [...]]]>

by Derek Davison

The three key timelines at the center of the negotiations between world powers and Iran over its nuclear program were the subject of a panel discussion at the Wilson Center today. Jon Wolfsthal of the Center for Nonproliferation Studies spoke about the duration of a hypothetical comprehensive agreement, Daryl Kimball of the Arms Control Association (ACA) discussed Iran’s “breakout” period, and Robert Litwak of the Wilson Center talked about possible timeframes for sanctions relief.

While there may be flaws in the P5+1’s (US, UK, France, China, and Russia plus Germany) decision to make “breakout” their primary focus, it is that timeline, and specifically its uranium enrichment component, that dominates the negotiations and related policy debates. Uranium enrichment capacity is, according to Kimball, the “key problem” in terms of coming to a final agreement, given that more progress seems to have been made between the two parties on limiting the Arak heavy-water reactor’s plutonium production, and on more intensive inspection and monitoring mechanisms. He also discussed the contours of a deal that would allow Iran to begin operating “next generation” centrifuges, which enrich uranium far more efficiently than the older models currently being operated by the Iranians.

Kimball’s suggestion mirrored a new piece in the ACA’s journal by Princeton scholars Alexander Glaser, Zia Mian, Hossein Mousavian, and Frank von Hippel. They proposed a two-stage process for modernizing Iran’s enrichment technology and eventually finding a stable consensus on the enrichment issue. In the first stage, to last around five years, Iran could begin to replace its aging “first generation” centrifuges with more advanced “second generation” centrifuges so long as Iran’s overall enrichment capacity remains constant, and it would be able to continue research and development on more modern centrifuge designs so long as it permitted inspectors to verify that those more advanced centrifuges were not being installed. That five year period would also allow Iran and the international community time to work out a more permanent uranium enrichment arrangement, which could take the form of a regional, multi-national uranium enrichment consortium similar to Urenco, the European entity that handles enrichment for Britain and Germany.

As the authors note, Iran is one of only three non-nuclear weapon states (Brazil and Japan are the others) that operate their own enrichment programs, so the global trend seems to be moving in the direction of these multi-national enrichment consortiums. It is unclear if Iran would agree to this kind of framework, but this piece was co-authored by Mousavian, who has ties to Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, suggesting that it could become acceptable to the Iranian government.

One major hurdle in the talks remains Iran’s desire, as noted by Kimball, to be able to fully fuel its Bushehr reactors with domestic enriched uranium by 2021, the year when its deal with Russia to supply fuel to Bushehr runs out. Fueling the Bushehr reactors alone would require vastly more enrichment capacity than the P5+1 would be able to accept, and Iran has plans for future reactors that it would presumably want to be able to fuel domestically as well. The P5+1 negotiators, and well-known non-proliferation organizations including ACA, argue that Iran can simply renew its fuel supply deal with Russia and thereby reduce its “need” for enriched uranium substantially. But from Iran’s perspective, domestic enrichment is its only completely reliable source of reactor fuel. Indeed, Russia has historically proven willing to renege on nuclear fuel agreements in the name of its own geopolitical prerogatives. Any final deal that relies on outside suppliers to reduce Iran’s enriched uranium requirements will have to account for Iranian concerns about whether or not those outside suppliers can be trusted. It’s possible that the kind of enrichment consortium described in the ACA piece will satisfy those concerns.

The other timelines in question, the overall duration of a deal and the phasing out of sanctions, spin off of the more fundamental debate over enrichment capacity, and both revolve around issues of trust. Wolfsthal argued that the P5+1 may require a deal that will last at least until Rouhani is out of office, in order to guard against any change in nuclear posture under the next presidential administration. In his discussion of sanctions relief, Litwak pointed to an even more fundamental question of trust: is Iran willing to believe (and, it should be added, can Iran believe) that the United States is prepared to normalize relations with the Islamic Republic and to stop making regime change the paramount goal of its Iran policy? If the answer is “yes,” then Iran may be willing to accept a more gradual, staged removal of sanctions in exchange for specific nuclear goals, which the P5+1 favors. If the answer is “no,” then Iran is likely to demand immediate sanctions relief at levels that may be too much, and too quick for the P5+1 to accept.

]]>by Jasmin Ramsey

The title of this post is a quote from Shaul Bakhash, a George Mason University professor who moderated a panel discussion, “Iran, the Next Five Years: Change or More of the Same?“ at the Wilson Center today. “In a way, we’ve been here before,” said the esteemed scholar, referring [...]]]>

by Jasmin Ramsey

The title of this post is a quote from Shaul Bakhash, a George Mason University professor who moderated a panel discussion, “Iran, the Next Five Years: Change or More of the Same?“ at the Wilson Center today. “In a way, we’ve been here before,” said the esteemed scholar, referring to the presidencies of centrist leader Hashemi Rafsanjani and Mohammad Khatami, when the country was perceived as moving towards openness at home and abroad. But while Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s administration includes individuals with past ties to those movements, Bakhash says the conservatives “remain the strongest political body in Iran”.

While nothing can stay the same forever, many people worried (some still do) that the Islamic Republic would continue down a path of conservatism verging on radicalism before the surprise presidential election of Rouhani in June 2013. Since Rouhani took over from Mahmoud Ahmadinejad — whose former conservative allies couldn’t effectively unite in time to support another conservative into the presidency — those worries have changed. Now the question on everyone’s mind is: can Rouhani successfully navigate Iran’s contested political waters in his quest to implement foreign, economic and social policy reforms?

A lot depends on Iran’s 2016 parliamentary elections, according to panelist Bernard Hourcade, an expert on Iran’s social and political geography. “Elections matter In Iran”, said Hourcade, echoing Farideh Farhi. What happened in 2009 (when large groups of Iranians protested the election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and were violently repressed) proved that “elections have become a major political and social item in [Iranian] political life.”

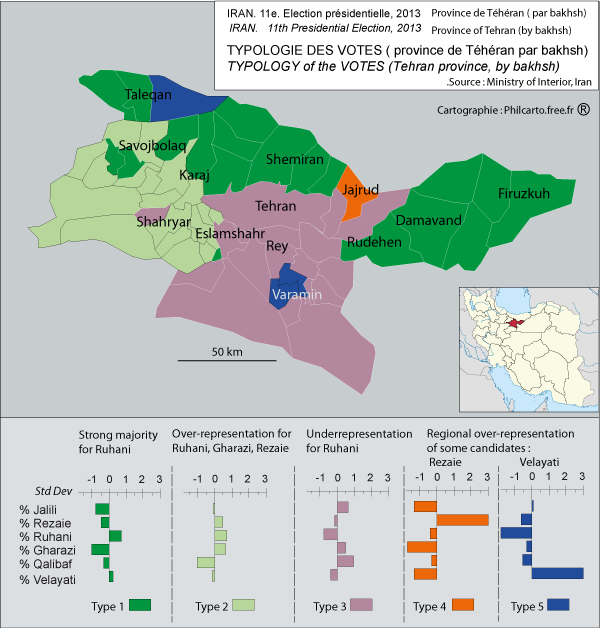

Hourcade uses official data to back up that point. Most interestingly, he shows that due to population migration patterns, the most important political divisions no longer exist between Iranian cities and villages, but between city centers and suburbs. Consider, for example, the typology of presidential votes for Rouhani in Tehran province. Hourcade’s diagram shows that while Rouhani had strong support in the northern part of Shemiran, he didn’t get a majority in central Tehran. Why that occurred is more difficult to answer, according to Hourcade, due to limited data resources.

Hourcade uses official data to back up that point. Most interestingly, he shows that due to population migration patterns, the most important political divisions no longer exist between Iranian cities and villages, but between city centers and suburbs. Consider, for example, the typology of presidential votes for Rouhani in Tehran province. Hourcade’s diagram shows that while Rouhani had strong support in the northern part of Shemiran, he didn’t get a majority in central Tehran. Why that occurred is more difficult to answer, according to Hourcade, due to limited data resources.

How political divisions play out in Iran’s upcoming parliamentary elections, which could give Iran’s currently sidelined conservatives more power, will also impact the Majles’ (parliament’s) reaction to the potential comprehensive deal with world powers over Iran’s nuclear program.

In other words, even if Iran’s rock star Foreign Minister can negotiate a final deal with the P5+1 (the U.S., Britain, France, China, and Russia plus Germany) that Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei approves, Iran’s parliament still has to ratify it, and if conservatives who oppose Rouhani dominate the majles, we may have another problem on our hands.

There were many other important points offered by Hourcade and his co-panelists, including Roberto Toscano, Italy’s former ambassador to Iran. He noted that former President Mohammad Khatami didn’t have the same chances as Rouhani because he was “too much out of the mainstream”. Rouhani, a centrist cleric and former advisor to Ayatollah Khamenei, wouldn’t have won the presidency without pivotal backing by both Khatami and Rafsanjani. So, as Toscano argues, Rouhani is in the mainstream (for now). But whether he and his allies will be able to maintain support from these important players moving forward, especially in 2016, will seriously influence whether he, like Khatami and Rafsanjani will be ultimately sidelined, or achieve a presidential legacy in Iran like nothing we’ve seen before.

Photo: Iranian President Hassan Rouhani walks by former Presidents Mohammad Khatami and Hashemi Rafsanjani following his June 2013 presidential vicotry. Credit: Mehdi Ghasemi/ISNA

]]>by Jasmin Ramsey

Press reports about medical supply shortages in Iran, some of which have described devastating consequences, have been surfacing in the last two years, while debate rages on about who’s responsible — the Iranian government or the sanctions regime. Siamak Namazi, a Dubai-based business consultant and former Public Policy [...]]]>

by Jasmin Ramsey

Press reports about medical supply shortages in Iran, some of which have described devastating consequences, have been surfacing in the last two years, while debate rages on about who’s responsible — the Iranian government or the sanctions regime. Siamak Namazi, a Dubai-based business consultant and former Public Policy Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars, admits the Iranian government shares responsibility but says sanctions are the main culprit. Humanitarian trade may be exempted from the sanctions, says Namazi, but that isn’t enough when the banking valve required to carry out the transactions is being strangled. “[I]f [sanctions advocates] maintain the sanctions regime is fine as it is, then how come they try to promote substitution from China and India?” asks Namazi. The following Q&A with Namazi was conducted in Washington, DC.

Q: You recently authored a policy paper published by the Woodrow Wilson Center where you essentially blame medical shortages in Iran on Western sanctions. How did you reach this conclusion?

Siamak Namazi: We concluded that the Iranian government deserves firm criticism for mismanagement of the crisis, poor allocation of scarce foreign currency resources and failing to crack down on corrupt practices, but the main culprit are the sanctions that regulate financial transactions with Iran. So, while Tehran can and should take further steps to improve the situation, it cannot solve this problem on its own. As sanctions are tightened more and more, things are likely to get worse unless barriers to humanitarian trade are removed through narrow adjustments to the sanctions regime.

My team and I reached these conclusions after interviewing senior officers among pharmaceutical suppliers, namely European and American companies in Dubai, as well as private importers and distributors of medicine in Tehran. We also spoke to a number of international banks. None of us had any financial stake in the pharmaceutical business, whatsoever, and we all worked pro bono.

Q: What is your basis for this claim given the humanitarian exemptions to the sanctions regime that allow for the trade of food and medicine?

Siamak Namazi: The US Congress deserves kudos for passing a law making it abundantly clear that humanitarian trade in food, agricultural products, medicine and medical devices are exempted from the long list of sanctions against Iran. This law is the reason why the Western pharmaceuticals can do business in Iran. I sincerely applaud that gesture.

Unfortunately, what we see is a case of what lawyers refer to as “frustration of purpose.” Iran can in theory purchase Western medicine, but in practice it is extremely difficult to pay for the lifesaving drugs it needs. Despite the Congressional directive, a number of Executive Orders that restrict financial transactions with Iran remain in place, making it all but impossible to implement that exception.

Sanctions also limit Iran’s access to hard currency. The country’s oil sales are seriously curtailed and have effectively been turned into a virtual barter with the purchasing country, mainly China and India.

Q: Not all Iranian banks are blacklisted by the US and there is a long list of small and large international banks that could carry out humanitarian transactions. Why can’t Iran use these channels for importing the medicine it needs?

Siamak Namazi: The non-designated Iranian banks are small and lack the international infrastructure required to wire money from Tehran to most foreign bank accounts. They rely on intermediary banks to process such transactions. Unfortunately, it’s extremely difficult, if not outright impossible, for these Iranian banks to find such counterparts, even when they are trying to facilitate fully legal humanitarian trade.

In the end, Iran needs to go through many loops and plays a constant cat and mouse game, creatively trying to find a channel to pay its Western suppliers of medicine. Not only does this increase the costs of medicine for the Iranians, it also causes major delays. In the meanwhile, pharmacy shelves run empty of vital drugs and the patient suffers.

Q: Isn’t that just a reflection of the international banks being too cautious rather than shortcomings in US sanctions laws? In a recent testimony to the Senate, US Treasury Undersecretary David Cohen was clear that no special permission is required to sell humanitarian goods to Iran and foreign financial institutions can facilitate these permissible humanitarian transactions.

Siamak Namazi: What Mr. Cohen actually said is that all is fine “as long as the transaction does not involve a U.S.-designated entity,” meaning a sanctioned Iranian bank.

How, exactly, does an international financial institution guarantee that none of Iran’s main banks, all of which are blacklisted, were involved in any part of the long chain involving a foreign currency transfer from Iran? Recall that foreign currency allocation for pharmaceutical imports start with the Central Bank of Iran, which is blacklisted. Maybe the CBI wired these funds to the non-designated Iranian bank from monies it holds in say, Bank Tejarat or Bank Melli, potentially adding further layers of banned banks to the chain.

Given the severity of the risk involved — fines that have reached nearly $2 billion in recent months — international banks seek clear indemnity. They want legal clarification that basically says, “You will not be fined for clearing humanitarian trade with Iran, period.”

So far Treasury has refused to grant such a measure, though recent comments by senior officials suggest that the US government has sent out delegations reassuring the banks, without actually making any changes to the letter of the law. While this is a welcome move, and indeed one of the recommendations in the report published by the Wilson Center, it is far from sufficient.

Q: You say that Iran has a hard time finding a banking channel to pay for Western medicine. At the same time, for the first time in many years, Iran purchased $89 million in wheat from the US in 2012. Why were they able to find a banking channel to pay for wheat, but have difficulty purchasing medicine?

Siamak Namazi: My claim is supported by recent US trade statistics showing that exports of pharmaceuticals to Iran dropped by almost 50 percent, but these numbers are ultimately misleading. My understanding is that US trade data only reflects exports from an American port, directly entering an Iranian port, which is a thin slice of the overall trade. This is while most companies send their goods to Dubai, Europe or Singapore and cover the entire Middle East, including Iran, from these hubs. So, when the statistics refer to a drop of sales of medicine from around $28 million in 2011 to half that figure in 2012, the figure grossly misrepresents the scale of the problem.

Let me stress this point again: the loss of $14 million in American-made drugs does not make for a crisis. The real problem is exponentially bigger than this. We are talking about the loss of hundreds of millions of dollars worth of American and European medicine.

You must also keep in mind supplier power in trade. Wheat is a perfectly substitutable good, so Iran is bound to find one supplier that is willing to sell its wheat with extended credit terms, until it secures the hard currency and banking channel to pay for it. A vital drug is often perfectly un-substitutable; meaning that a single company — most often American or European in the case of the most advanced medicines — enjoys a 20-year patent to manufacture it. So if Iran cannot find a banking channel to reimburse the manufacturer for it, it will have to do without that medicine until it can pay.

Q: Why can’t Iran procure its medicine from China, India or Japan — the countries it’s selling oil to?

Siamak Namazi: Iran has already increased its purchase of medicine and medical equipment from all the countries you listed. However, as I stated earlier, due to the highly regulated and patented nature of the pharmaceutical business, vital drugs are often un-substitutable.

Even when there is an alternative drug made by the Chinese, Indians or Japanese, there is an additional barrier. Medicine has to be registered before its importation is permitted. Just like the US has the Food and Drug Administration, Iran, like most countries, has an equivalent body that must approve the medicine. The specific molecule must be registered after thorough testing. In Iran, this process takes an exceedingly long time and should no doubt be improved, though recently they have taken steps to expedite it by making exceptions. The Ministry of Health sometimes allows a drug that was approved for sale in another country to also be imported and sold in Iran. But this rushed process has had major consequences in terms of side-effects. There are even press reports of deaths when substandard drugs were imported.

To be honest, I don’t understand the logic of the advocates of this solution. They argue that the existing humanitarian waivers are sufficient and claim any shortage of medicine in Iran is the consequence of Tehran’s own mismanagement. I have even heard accusations that Iran is intentionally creating such shortages to create public outrage against the US. But if they maintain the sanctions regime is fine as it is, then how come they try to promote substitution from China and India? Besides denying Iranian patients their right to receive the best treatment there is, aren’t they also rejecting the American pharmaceutical companies’ right to conduct perfectly legitimate business?

Q: To be fair, Iran’s own former health minister, Marzieh Vahid Dasjerdi, also accused the government of failing to allocate the necessary resources and lost her job after doing so.

Siamak Namazi: I actually commend the former health minister for her courageous intervention and have also voiced my concern about the misallocation of hard currency in various forums.

That said, I am not in a position to know or comment on the exact nature or circumstances of her dismissal. I can only reference our direct research and findings. We found and verified ample cases where Iran had allocated hard currency for vital medicine, yet the purchase fell through because they could not find a banking channel. This includes the sale of an anti-rejection drug needed for liver transplants by an American pharmaceutical that ultimately failed. Can you imagine waiting years for a donor and when your operation time arrives, being told that you cannot have it because the drug you need is missing?

You need not take our word for it. It is very easy for the US government to verify our claims by talking to the American pharmaceuticals that do business with Iran, or even by reviewing some of OFACs own files. In fact, the US industry lobby USA*Engage recently wrote a letter refuting Undersecretary Cohen’s claims that American companies have no problems dealing with Iran. In their own words: “Despite … clear Congressional directive and long-standing policy, the U.S. Treasury implements Executive Branch unilateral banking sanctions in a manner that blocks the financial transactions necessary for humanitarian trade.”

Q: So is there a solution to all this?

Siamak Namazi: Absolutely, and I have spelled it out in my op-ed in the International Herald Tribune and also in the Wilson Center report. It simply makes no sense to say humanitarian trade is legal, but the banking channel needed to facilitate the trade is restricted. In the case of medicine, the solution is arguably simpler than other humanitarian goods. With fewer than 100 American and European companies holding patents to the most advanced drugs needed, we can craft narrow, but unambiguous exemptions to the banking restrictions, essentially allowing these companies to sell medicine to Iran without undermining the sanctions regime overall.

To address the shortage of hard currency, Iran should be allowed to convert some of its current holdings in Chinese, Indian and other banks around the world into hard currencies for the exclusive purpose of buying medical supplies. Alternatively, the US could revisit its earlier decision on the matter and allow European companies that owe billions of dollars to Iran to settle this debt by paying a pharmaceutical company on Iran’s behalf.

US policymakers are reminded that medicine is highly subsidized in Iran. Imported drugs receive hard currency allocations at a greatly subsidized rate and are again supported through government-owned insurance companies. That means that the Iranian government ultimately gains far fewer rials for every dollar it allocates to an importer of medicine than it does selling its hard currency to importers of most other goods.

– Siamak Namazi, a Middle East specialist whose career spans the consulting, think tank and non-profit worlds, is currently a consultant based out of Dubai. His former positions include the managing director of Atieh Bahar Consulting, an advisory and strategic consulting firm in Tehran. He has also carried out stints as a fellow in the Wilson Center for International Scholars, the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the National Endowment for Democracy. A frequent contributor to international publications and conferences, he has authored chapters in six books and appeared regularly as a commentator in the international media. He holds an MBA from the London Business School, an MS in Planning & Policy Development from Rutgers University, and a BA in International Relations from Tufts University.

]]>by Jasmin Ramsey

Two conversations are presently occurring in Washington about Iran. Hawks and hardliners are searching for new ways to force the Obama administration to tighten or impose further sanctions, and/or discussing when the US should strike the country. Meanwhile, doves and pragmatists have been pointing out the ineffectiveness of sanctions in [...]]]>

by Jasmin Ramsey

Two conversations are presently occurring in Washington about Iran. Hawks and hardliners are searching for new ways to force the Obama administration to tighten or impose further sanctions, and/or discussing when the US should strike the country. Meanwhile, doves and pragmatists have been pointing out the ineffectiveness of sanctions in changing Iran’s nuclear calculus (even though the majority of them initially pushed for these sanctions) as well as the many cons of military action. Although the hawks and hardliners tend to be Republican, the group is by no means partisan. And these conversations do converge and share points at times, for example, the hawks and hardliners also complain about the ineffectiveness of sanctions, but in the context of pushing for more pressure and punishment.

That said, both sides appear stuck — the hawks, while successful in getting US policy on Iran to become sanctions-centric, can’t get the administration or military leaders to buy their interventionist arguments, and the doves, having previously cheered sanctions as an alternative to military action, appear lost now that their chosen pressure tactic has proven ineffective.

Hawks and Doves Debate Iran Strike Option

On Wednesday, the McCain Institute hosted a live debate that showcased Washington positions on Iran, with the pro-military argument represented by neoconservative analyst Danielle Pletka of the American Enterprise Institute and Democrat Robert Wexler, a member of the US House of Representatives from 1997-2010, and two prominent US diplomats on the other side — Ambassadors Thomas R. Pickering, who David Sanger writes “is such a towering figure in the State Department that a major program to train young diplomats is named for him”, and James R. Dobbins, whose distinguished career includes service as envoy to Kosovo, Bosnia, Haiti and Somalia.

Only the beginning of this recording (I can’t find any others) is hard to hear, and you won’t regret watching the entire lively discussion, particularly because of Amb. Pickering’s poignant responses to Pletka’s flimsy points — she inaccurately states IAEA findings on Iran’s nuclear program and claims that, even though she’s no military expert, a successful military operation against Iran wouldn’t necessarily include boots on the ground. In fact, experts assess that effective military action against Iran aimed at long-term positive results (cessation of its nuclear program and regime change) would be a long and arduous process, entailing more resources than Afghanistan and Iraq have taken combined, and almost certainly involving ground forces and occupation.

Consider some the characteristics of the pro-military side: Wexler repeatedly admits he made a mistake in supporting the war on Iraq, but says the decision to attack Iran should “presuppose” that event. Later on he says that considering what happened with Iraq, he “hopes” the same mistake about non-existent WMDs won’t happen again. Pletka, who endorsed fighting in Iraq until “victory” had been achieved (a garbled version of an AEI transcript can be found here), states in her opening remarks that the US needs to focus on ”what happens, when, if, negotiations fail” and leads from that premise, which she does not qualify with anything other than they’re taking too much time, with arguments about the threat Iran poses, even though she calls the Iranians “very rational actors”.

While Wexler’s support for a war launched on false premises seriously harms his side’s credibility, it was both his and Pletka’s inability to advance even one indisputable interventionist argument, coupled with their constant reminders that they don’t actually want military action, that left them looking uninformed and weak.

The diplomats, on the other hand, offered rhetorical questions and points that have come to characterize this debate more generally. Amb. Pickering: “Are we ready for another ground war in the Middle East?”, and, “we are not wonderful occupiers”. Then on the status of the diplomatic process: “we are closer to a solution in negotiations than we have been before”. Amb. Dobbins meanwhile listed some of the cons of a military operation — Hezbollah attacks against Israel and US allies, interruptions to the movement of oil through the vital Strait of Hormuz, a terror campaign orchestrated by the Iranians — and then surprised everyone by saying that these are “all things we can deal with”. A pause, then the real danger in Amb. Dobbins’ mind: that “Iran would respond cautiously”, play the aggrieved party, withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, kick out IAEA inspectors and accelerate its nuclear program at unknown sites. Then what, the audience was left to wonder. Neither Pletka nor Wexler offered an answer.

The Costs of War With Iran and the C-Word

While watching the McCain debate, I wondered if Pletka and Wexler would consider reading a recently published book by Geoffrey Kemp, an economist who served as a Gulf expert on Reagan’s National Security Council and John Allen Gay, entitled War With Iran: Political, Military, And Economic Consequences. This essay lays out the basis of the work, which mainly focuses on the high economic costs of war, so I won’t go into detail here, but yesterday during the book’s launch at the Center for National Interest (CNI), an interesting comment was made about the “C-Word”. Here’s what Kemp said during his opening remarks, to an audience that included everyone from prominent foreign policy experts and former government officials, to representatives from Chevron and AIPAC:

You certainly cannot, must not, underestimate the negative consequences if Iran does get the bomb…But I think on balance, unlike Senator McCain who said that the only thing worse than a war with Iran is an Iran with a nuclear weapon…the conclusion of this study is that war is worse than the options, and the options we have, are clearly based on something that we call deterrence and something that we are not allowed to call, but in fact, is something called containment. And to me this seems like the most difficult thing for the Obama administration, to walk back out of the box it’s gotten itself into over this issue of containment. But never fear. Successive American administrations have all walked back lines on Iran.

Interestingly, no one challenged him on this during the Q&A. And Kemp is not the only expert to utter the C-Word in Washington — he’s joined by Paul Pillar and more reluctant distinguished voices including Zbigniew Brzezinksi.

Diplomacy as the Best Effective Option

Of course, if more effort was concentrated on the diplomacy front, as opposed to mostly on sanctions and the military option, Iran could be persuaded against building a nuclear weapon. Consider, for example, US intelligence chief James Clapper’s statement on Thursday that Iran has not yet made the decision to develop a nuclear weapon but that if it chose to do so, it might be able to produce one in a matter of “months, not years.” Clapper told the Senate Armed Services Committee that “[Iran] has not yet made that decision, and that decision would be made singularly by the supreme leader.”

It follows from this that while the US would be hard pressed in permanently preventing an Iranian nuclear weapon (apart from adopting the costly and morally repulsive “mowing the lawn” option), it could certainly compel the Iranians to make the decision to rush for a bomb by finally making the military option credible — as Israel has pushed for — or following through on that threat.

So where to go from here? Enter the Iran Project, which has published a series of reports all signed and endorsed by high-level US foreign policy experts, and which just released it’s first report with policy advise: “Strategic Options for Iran: Balancing Pressure with Diplomacy”. There’s lots to be taken away from it, and Jim Lobe, as well as the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal have covered it, but it ultimately boils down to the notion that the US needs to rethink its policy with Iran and creatively use the leverage it has gotten from sanctions to bring about an agreement. Such an agreement will likely have to be preceded by bilateral talks and include some form of low-level uranium enrichment on Iranian soil and sanctions relief if Iran provides its own signifiant concessions. The report also argues for the US to engage with Iran on areas of mutual interest, including Iraq and Afghanistan.

During the Wilson Center report launch event, Amb. Pickering summed up the status of negotiations with Iran as follows: “Admittedly we should not expect miraculous moves to a rapid agreement, but we’re engaged enough now to have gone beyond the beginning of the beginning. We’re not at the end of the beginning yet, but we’re getting there.” Later, Jim Walsh, a member of the task force and nuclear expert at MIT pointed out that 20-percent Iranian uranium enrichment, which everyone is fixated on now, only became an issue after Iran stopped receiving fuel for its Tehran Research Reactor and began producing it itself. In other words, the longer the US takes to give Iran a deal it can stomach and sell at home, the more the Iranians can ask for as their nuclear program progresses. “The earlier we can get a deal, the better the deal is likely to be,” he said.

]]>by Siamak Namazi

The United States Treasury has issued a new explanation for the shortage of medical drugs and equipment in Iran. They claim the Iranian government is intentionally trying to exploit the problem for political purposes. A senior US Treasury official recently pointed to just-released US International Trade Statistics (USITS) [...]]]>

by Siamak Namazi

The United States Treasury has issued a new explanation for the shortage of medical drugs and equipment in Iran. They claim the Iranian government is intentionally trying to exploit the problem for political purposes. A senior US Treasury official recently pointed to just-released US International Trade Statistics (USITS) to support this claim, arguing that while these figures show falling medicine exports to Iran, the export of wheat has gone up, therefore, Iran could use whatever banking it used for the wheat to procure medicine.

Not really. At least the data that’s being referred to proves no such thing.

The USITS data showed a drop from $31.2 million to $14.8 million in US pharma exports from the US to Iran between 2011 and 2012. These figures are highly misleading and seriously discount the scale of the problem. I checked the sales figures of a single large US pharmaceutical company (on the conditional of anonymity) with the person in charge of them out of Dubai. Well, this American company alone experienced a drop of sales to Iran from around $50 million to $20 million during the same time period.

The USITS data simply shows what goods left the US directly for Iran. This is while the US pharma company is likely to have supplied Iran with drugs from a manufacturing or storage facility in Europe, Dubai or Singapore.

The food figures are just as inconclusive. Sure, they went up because of an $89 million sale of wheat in 2012. Keep in mind that $89 million is nothing; it’s peanuts for a country that often imports over $1 billion of wheat. Such a figure probably amounts to one or two single orders at best. When did that take place? Early 2012, before the tightening of sanctions? Was it part of the $1.4 billion Shell-Cargill deal allowing Shell to pay its debts to Iran by crediting Iran’s account with Cargill (if that actually went through?).

All in all, the trade figures of the USITS are irrelevant to the debate at hand.

There are many arguments among pundits when it comes to the overall effectiveness of sanctions against Iran and whether or not they will ultimately persuade decision-makers in Tehran to change their nuclear policies.

But the effect of sanctions on the shortages of medical equipment and drugs in Iran is much easier to assess. Talk to the people in charge of the Iran account among the American and European pharma companies and ask them where the problem is. It’s not that hard to understand: these companies need to get paid and banking channels are very limited while Iran has a shortage of hard currency (I mean Euros and Dollars, not Rupees and Yuan); therefore, the amount of trade is curtailed. Perhaps the fact that only one international bank remains willing to brave the wrath of US sanctions — even though we are talking about fully legal trade under humanitarian exemptions — lends further testimony to where the main problem exists.

Let me be perfectly clear: sanctions are not the sole problem here. The Iranian government deserves stern criticism for its maladroit handling of the shortages of medicine and medical products. It must dramatically improve its foreign currency allocation competence and transparency, as well as governance of the sector, and it must crackdown on corrupt practices.

However, the Iranian government alone cannot solve the issue of Western medicinal shortages. Sanctions are a major impediment and unless Washington and Brussels rethink the humanitarian waivers — specifically by removing the banking bottleneck and allowing Iran to convert some of the money it earns from oil sales to Euros and Dollars for the narrow purpose of clearing trade debt related to medical drugs and equipment — this problem is going to get worse, not better.

A recent study that a group of independent consultants conducted for the Wilson Center explains this issue’s various complications and their solutions in more detail.

– Siamak Namazi is a Dubai-based consultant and a former Public Policy Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars.

]]>The Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS) has released a brief report emphasizing that Iran continues to move toward nuclear weapons capability and the international community must halt further progress. ISIS’s latest concern centers around Iranian lawmaker Mansour Haqiqatpour’s October 2 comment that Iran could enrich uranium to 60 percent [...]]]>

The Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS) has released a brief report emphasizing that Iran continues to move toward nuclear weapons capability and the international community must halt further progress. ISIS’s latest concern centers around Iranian lawmaker Mansour Haqiqatpour’s October 2 comment that Iran could enrich uranium to 60 percent if diplomatic talks fail. From Reuters:

“In case our talks with the (six powers) fail to pay off, Iranian youth will master (the technology for) enrichment up to 60 percent to fuel submarines and ocean-going ships,” Haqiqatpour said.

The powers should know that “if these talks continue into next year, Iran cannot guarantee it would keep its enrichment limited to 20 percent. This enrichment is likely to increase to 40 or 50 percent,” he said.

The US and international community should prepare for an official Iranian announcement of such high-grade enrichment, warns ISIS, adding that Iran has “no need to produce highly enriched uranium at all, even if it wanted nuclear fuel for a reactor powering nuclear submarines or other naval vessels, or for a research reactor”. The move would also “significantly shortens Iran’s dash time to reaching weapon grade uranium,” the report said.

ISIS’s conclusion:

Taken in this context, any official Iranian announcement to make highly enriched uranium should be seen as unacceptable. Many will view such a decision as equivalent to initiating a breakout to acquire nuclear weapons, reducing any chance for negotiations to work and potentially increasing the chances for military strikes and war. Before Iran announces official plans to make highly enriched uranium, the United States and the other members of the P5+1 should quietly but clearly state to Iran what it risks by producing highly enriched uranium under any pretext.

No details are provided as to what exactly needs to be done to make Iran understand that such a move would be “unacceptable”, but we are informed that Iranian enrichment of high-grade uranium would increase the chances for military conflict.

The fact that Iran is still years aways from being able to test a device, and according to US and international official assessments has still not made the decision to do so, is also absent from ISIS’s report. Indeed, according to the bipartisan Iran Project report on the benefits and costs of military action on Iran (emphasis mine):

]]>After deciding to “dash” for a bomb, Iran would need from one to four months to produce enough weapons-grade uranium for a single nuclear device. Additional time—up to two years, according to conservative estimates—would be required for Iran to build a nuclear warhead that would be reliably deliverable by a missile. Given extensive monitoring and surveillance of Iranian activities, signs of an Iranian decision to build a nuclear weapon would likely be detected, and the U.S. would have at least a month to implement a course of action.

I’ve been meaning to write about this report on the multifold human costs of militarily striking Iran’s nuclear facilities and am happy to find that it’s already been noted by Golnaz Esfandiari as well as Gordon Lubold, among others. (Marsha Cohen’s well-read Lobe Log post on [...]]]>

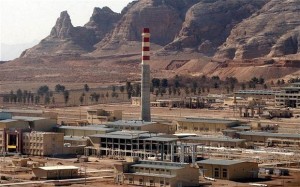

I’ve been meaning to write about this report on the multifold human costs of militarily striking Iran’s nuclear facilities and am happy to find that it’s already been noted by Golnaz Esfandiari as well as Gordon Lubold, among others. (Marsha Cohen’s well-read Lobe Log post on the same topic was the closest thing to such a study that I’ve come across so far.) “The Ayatollah’s Nuclear Gamble” is sponsored by Utah’s Hinckley Institute of Politics and was authored by Khosrow B. Semnani, an Iranian-American engineer by training and philanthropist. It will be featured this week at a joint event by the Woodrow Wilson Center and the Iran Task Force at the Atlantic Council. With the study Semnani endeavors to scientifically prove something which seems obvious: attacking nuclear facilities in Iran could have devastating effects on possibly hundreds of thousands of Iranians who would be exposed to highly toxic chemical plumes and even radioactive fallout. Case studies were conducted on the Iranian cities of Isfahan, Natanz, Arak, and Bushehr. In Isfahan, a military strike on the nuclear facility there “could be compared to the 1984 Bhopal industrial accident at the Union Carbide plant in India”:

I’ve been meaning to write about this report on the multifold human costs of militarily striking Iran’s nuclear facilities and am happy to find that it’s already been noted by Golnaz Esfandiari as well as Gordon Lubold, among others. (Marsha Cohen’s well-read Lobe Log post on the same topic was the closest thing to such a study that I’ve come across so far.) “The Ayatollah’s Nuclear Gamble” is sponsored by Utah’s Hinckley Institute of Politics and was authored by Khosrow B. Semnani, an Iranian-American engineer by training and philanthropist. It will be featured this week at a joint event by the Woodrow Wilson Center and the Iran Task Force at the Atlantic Council. With the study Semnani endeavors to scientifically prove something which seems obvious: attacking nuclear facilities in Iran could have devastating effects on possibly hundreds of thousands of Iranians who would be exposed to highly toxic chemical plumes and even radioactive fallout. Case studies were conducted on the Iranian cities of Isfahan, Natanz, Arak, and Bushehr. In Isfahan, a military strike on the nuclear facility there “could be compared to the 1984 Bhopal industrial accident at the Union Carbide plant in India”:

In that accident, the release of 42 metric tons (47 U.S. tons) of methyl isocyanate turned the city of Bhopal into a gas chamber. Estimates of deaths have ranged from 3,800 to 15,000. The casualties went well beyond the fatalities: More than 500,000 victims received compensation for exposure to fumes.

The environmental consequences would also be wide-ranging:

With the high likelihood of soluble uranium compounds permeating into the groundwater, strikes would wreak havoc on Isfahan’s environmental resources and agriculture. The Markazi water basin, one of six main catchment areas, which covers half the country (52%), provides slightly less than one-third of Iran’s total renewable water (29%) (Figure 26). According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the groundwater discharge in the basin from approximately 155,000 wells, 22,000 channels and 13,500 springs is the primary water source for agricultural and residential uses.106 It is almost certain that the contamination of groundwater as a result of strikes would damage this important fresh-water source.

The report also touches on the unintended consequences of militarily striking Iran, such as a “short or prolonged regional war” and explains, as reputable analysts have, why the Israeli strike on Iraq’s Osirak facility is a “false analogy”:

The Osirak analogy is the fantasy that there will be no blowback from strikes against Iran’s nuclear facilities. It discounts the complexity, severity, scale, consequences, and casualties such an operation would entail. Iran’s nuclear program is not an empty shell, nor is it a single remote target. The facilities in Iran are fully operational, they contain thousands of personnel, they are located near major population centers, they are heavily constructed and fortified, and thus difficult to destroy. They contain tons of highly toxic chemical and radioactive material. To grasp the political and psychological impact of the strikes, what our estimates suggest is that the potential civilian casualties Iran would suffer as a result of a strike — in the first day — could exceed the 6,731 Palestinians and 1,083 Israeli’s reported killed in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict over the past decade. The total number of fatalities in the 1981 Osirak raid was 10 Iraqis and one French civilian, Damien Chaussepied.

According to Greg Thielmann of the Arms Control Association, the report makes a “valuable contribution to “colorizing” the bloodless discussions of the “military option.” Thielmann, who formerly worked on assessments of ballistic missile threats at the State Department’s intelligence bureau, told Lobe Log that he had not seen “a more serious look at the medical consequences for the Iranian population” than provided by this report.

While Thielmann calls the report an “impressive effort”, he also offered criticism. “I take strong exception to the author’s introductory assertion that diplomacy with the Islamic Republic “requires a willful act of self-deception,” and that regime change is the only way to achieve an acceptable resolution to the challenges of Iran’s nuclear program,” he said.

Thielmann was also “surprised” that the strike scenario analyzed in the study includes the Bushehr facility, “which is of much less proliferation concern than the other nuclear facilities mentioned, and which, because of the extensive use of Russian personnel in operating the reactor there, would carry high political costs to attack. ”

“Such an attack would also violate Additional Protocol I of the 1949 Geneva Conventions,” said Thielmann, who provided the following excerpt from Article 56 of the 1977 Additional Protocol I:

1. Works and installations containing dangerous forces, namely dams, dykes and nuclear electrical generating stations, shall not be made the object of attack, even where these objects are military objectives, if such attack may cause the release of dangerous forces and consequent severe losses among the civilian population. Other military objectives located at or in the vicinity of these works or installations shall not be made the object of attack if such attack may cause the release of dangerous forces from the works or installations and consequent severe losses among the civilian population.

It will be interesting to see whether the report gets mainstream media attention following the Wilson Center event and if it will spark further examination of this integral — but otherwise barely mentioned — aspect of using the “military option” on Iran.

]]>