Rohafza spends her days sitting behind a padlocked grill door, immovable and staring at Maidani, the place her son is buried. The woman’s face is pale, and her hair is graying. For two years the door has stayed closed, barring Rohafza from seeing her son’s grave. It’s her family that is [...]]]>

Rohafza spends her days sitting behind a padlocked grill door, immovable and staring at Maidani, the place her son is buried. The woman’s face is pale, and her hair is graying. For two years the door has stayed closed, barring Rohafza from seeing her son’s grave. It’s her family that is keeping her gated – for her own safety, as they say – to prevent Rohafza from sneaking out at night to scream at the grave site.

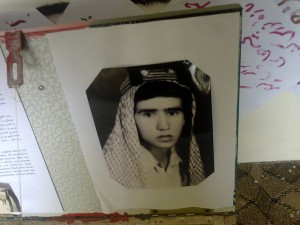

Zarmine (her back to the camera) prays in front of her brother Hashmatullah’s grave.

creidit: Sohaila Weda Khamoosh/Killid

With about 50 percent of adult Afghans suffering mental health problems, Rohafza’s story is one of millions who have undergone trauma in a war-torn country with little to no mental health services and archaic practices of handling mental illness at a family level – a combination that can make patients’ lives as tragic as the events that transformed them.

In Rohafza’s case it happened 18 years ago, when 17-year old Hashmatullah, her only son, was killed in the partisan war that followed the fall of the communist government of Afghanistan’s president Najibullah (1987-1992). Mujahedin groups that had been funded by the U.S. to fight the Soviet-backed government turned their guns on each other plunging the country into bloody civil war.

A rocket smashed into their neighbourhood killing Hashmatullah, her sister’s grandson and two of their classmates. “They were just coming back from school,” says Zarmina, one of Rohafza’s five daughters

Her father was sitting outside when suddenly there was a big blast and “Hashmat and his friends were thrown up in the air.” By the time they boy arrived at the hospital, the doctors’ efforts came too late.

“When they brought his body home, it was doomsday in our house. We sisters could hardly see the coffin for the crowds that had poured in to mourn with us,” Zarmina recalls.

According to the daughter, their son’s death unhinged both her parents, but it was her mother who lost her mind, leaving the family overwhelmed with caring for her. “Sometimes in the middle of the night we would see she was not in her bed. We would find her at Hashmatullah’s grave, screaming.”

When her mother tried to burn their house down, setting the carpets on fire, according to Zarmina, the family went ahead and tied her down with a chain. “But this only worsened her condition,” the daughter says.

As inadequate as the family’s response to Rohafza condition is, professional support is nearly non-existent in this country scarred by over three decades of war. Currently, a 60-bed clinic in Kabul is the only publicly run comprehensive mental health facility, while psychiatrists remain hard to come by. A 2006 joint report by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Afghanistan Ministry of Public Health lists the total number of psychiatrists countrywide at two.

In 2010, the situation showed little improvement, with two doctors and a total of 200 beds for psychiatric services countrywide, according to WHO in an article by AFP.

Afghanistan, however, is not an isolated case. Seventy-five percent of an estimated 450 million people with mental health issues live in developing countries, with many of them being shut away, rather than treated.

Back in their village in Afghanistan, Zarmira remembers how her brother was born after a great deal of prayer and fasting by her mother, as their father had threatened to abandon the family if their sixth child was a girl. When Rohafza gave birth to a boy, she named him Hashmatullah, meaning Greatness. But he would not live long enough to fulfill his promise, laments his sister.

* Sohaila Weda Khamoosh writes for Killid, an independent Afghan media group in partnership with IPS. By distributing the testimonies of survivors of war through print and radio, Killid strives for greater public awareness about people’s hopes and claims for justice, reconciliation and peace across Afghanistan.

]]>Shah Barat was a zookeeper at the Kabul Zoo when Taliban fighters marched into the city. As tens of thousands fled he stayed on to look after the animals in the zoo. In this testimony*, Shah Barat remembers the zoo’s former glory and subsequent devastation.

Before the Taliban took over [...]]]>

Shah Barat was a zookeeper at the Kabul Zoo when Taliban fighters marched into the city. As tens of thousands fled he stayed on to look after the animals in the zoo. In this testimony*, Shah Barat remembers the zoo’s former glory and subsequent devastation.

Before the Taliban took over the city in 1996, Kabul Zoo was home to 37 species. There was Marjan, the zoo’s much-loved lion, an Indian elephant, deer, birds and numerous other animals.

Taliban fighters killed some for food. A few more escaped and were never traced. The zoo, which was established in 1966, and counted as among Asia’s best, was ravaged by war. That some of the animals survived was due to the dedication of zookeepers like Shah Barat.

“I suffered many hardships, hunger and danger, but I did not let the animals in the zoo go hungry,” he says. “They are also the creatures of God and goodness to them is counted as being good in the eyes of God. Unfortunately the hard hearted people turned their guns on these dumb creatures.”

The young Shah Barat had sought employment in the zoo because of his love for animals from childhood. “I had a special sympathy for the animals in my village,” he says. “I had kept many in the house. Villagers knew me as an animal lover. When I saw a sick dog, I would take care of it. Actually my house was a small zoo!”

Ruined by war

Kabul was far from his village in Andar district, Ghazni province, but Shah Barat was determined to work only in a zoo. In 1988, he joined the Kabul Zoo. Five years later, at the time of the first major exodus of civilians from Kabul, he was considered one of the senior zookeepers with many staff members fleeing the incessant bombing by rival mujahedin factions jockeying for control. The mujahedin had formed the government after toppling the communist Najibullah regime in 1992. But the power-sharing arrangement was short-lived, and between 1993 and 1996 when the Taliban took over Kabul, power continuously shifted from one faction to the other.

“Every time a rocket was fired the animals were traumatised,” he recalls. “I never thought the great Kabul Zoo would be turned so soon into a ruin!”

The civil war years were a time when people cowered in their houses from fear, according to Shah Barat. The price of everything was sky high. Salaries were not paid on time, and when they were, it wasn’t enough for even a week. Still, the zoo keepers bought rations for the animals out of their own meager resources. “I kept my 10 children and wife hungry, but the animals were never hungry,” he says.

He speaks particularly warmly about his relationship with Marjan (meaning coral in Dari and Arabic), the zoo’s only lion. “Marjan was a gift from the Cologne Zoo. People came from all over the country to see him. He was our only source of income,” he recalls.

The zoo’s fortunes further dipped with the Taliban takeover of the city. The fighters showed no mercy for the animals, as groups of gunmen entered the zoo to tease and shoot.

Cruelty to animals

He remembers the day a gunman foolishly entered the lion’s enclosure and was torn to pieces. The next day his friends returned and threw a grenade in Marjan’s den. The unsuspecting lion was horribly maimed. “Marjan became blind in one eye. His jaw was full of shrapnel. He lost several teeth, which meant that he could not tear the meat he was fed. He couldn’t smell. He lived for another 10 years but he was a pale shadow of his former regal self,” he says.

He fondly remembers a monkey that was a gift from Nepal. She had become tame in the zoo and would even “eat her food with a spoon much to everyone’s delight,” he says. When the war broke out, and rockets rained from the sky, the caged animals were frantic with fear. “The war made her wild, and she escaped,” he says of the monkey.

When one day a bomb landed on the deer enclosure, he ran to see the damage, only to find that “All the deer were bathed in their blood.”

A rocket killed the zoo’s sole elephant.

After U.S. troops drove out the Taliban at the end of 2001, the horrendous abuse of animals was widely reported. The one-eyed lion Marjan became world famous and many zoos and organisations sent teams of experts to help rehabilitate the zoo.

Marjan died in January 2002. Shah Barat, now 55, still works for Kabul Zoo, earning 6,000 Afs (roughly 110 USD).

*Noor Wali Saeed Shinwarai writes for Killid, an independent Afghan media group in partnership with IPS. By distributing the testimonies of survivors of war through print and radio, Killid strives for greater public awareness about people’s hopes and claims for justice, reconciliation and peace across Afghanistan.

]]>Years of war have turned Afghanistan into one of the most mined countries in the world. Landmines have killed and maimed tens of thousands. In this testimony, 28-year-old Mahro recalls the day she came upon unexploded ordnance that robbed her of her sight and the use of one hand.

In 1994, the [...]]]>

Years of war have turned Afghanistan into one of the most mined countries in the world. Landmines have killed and maimed tens of thousands. In this testimony, 28-year-old Mahro recalls the day she came upon unexploded ordnance that robbed her of her sight and the use of one hand.

In 1994, the family was living in Qala-e-Haidar Khan next to Arghandi in Kabul province. They owned cows, and the sale of milk was their main livelihood. As the youngest, it was Mahro’s job to take the cows out to pasture. She remembers how, on one fateful day, she was grazing the family’s cows near a military post with her aunt’s son. “He pulled out something that was half buried in the ground, and hit it with a stone,” she remembers. When the landmine exploded, her cousin, only a bit older than she, died in the blast.

Every side in the successive rounds of fighting in Afghanistan has planted anti-personnel mines. They have been laid in residential areas and on agricultural land. Landmines were planted by the communist regime of President Najibullah, during the fighting with U.S.-supported mujahedin groups. The mujahedin, in turn, mined tracks to villages to prevent the advance of Soviet tanks. Further mine-laying took place between 1996 and 2001 during the conflict between the Taliban government and the Northern Alliance led by Ahmad Shah Massoud. Even today 45 people on average lose their limbs every month to deadly anti-personnel mines, according to Engineer Abdul Wakil, head of the Mine Action Coordination Centre of Afghanistan.

Littered with landmines

Mahro says it was a soldier who had pointed out the grassy knoll by the military post and told the children to take the cows there. “My cousin knew the area well. He had found shards of artillery there. But he did not know the grass could be hiding unexploded landmines,” she says.

Mahro says at the time of the incident a war was raging between mujahedin groups. “There were no Christians or Jews in Afghanistan. The war was among the mujahedin.” Christians and Jews is a reference to the U.S.-led international troops in the country since 2001.

Mahro’s father, who did not want his name revealed, describes it as a time when everyone was armed. He is matter of fact when he recalls the accident that changed his daughter’s future. “They (Mahro and her cousin) were foolish,” he says without a trace of emotion on his face. “They went to a military post, and hit a mine with a stone. The boy was killed and the girl lost her eyes.”

For 40 days, Mahro was in hospital. Her father says she drifted between life and death.

“She had suffered grave injuries, and we rushed her to the Jamhuriat Hospital. But when she was not getting better, we moved her to Sehat-e-Tefel (Indira Gandhi Children’s Hospital in Kabul).”

Utter frustration

At first it seemed one of her eyes could be saved, but doctors operated because they feared her brain would suffer permanent damage. After 40 days the Red Crescent flew Mahro to Germany for further treatment. She learnt how to use her lame hand, but her blindness was beyond treatment.

“I returned to the country after one year. I was in depression, though I was only a child,” Mahro remembers. “I did not have a specific problem, I was free to move around the house, but I was very sad.”

One problem that nagged her was the fact that she could not recall parts of the Holy Quran and some of Hafiz’s poems (a great Persian poet) that she had learnt by heart before the accident. “I would keep telling my family I have forgotten whatever I’ve learnt.”

Slowly she adapted to living without the gift of sight. What she had forgotten, she relearnt with the help of an aunt, uncle and two siblings. She learnt the holy book by heart – the commentary, translation and rules of reciting. “I was always interested in the Holy Quran,” she says, recalling how she stayied with a relative for eight months to study it. He was also Hafiz – one who has learnt the Holy Quran by heart, she says. “I stayed for eight after she got out of the hospital. “When I returned home, I kept learning.,” she says, until, with the help of cassette tapes, she finally mastered the full 30 chapters.

Since 2007 she has been a teacher of the holy book. Now 28, she lives in Kabul’s Gulbagh area where she teaches more than 40 students. “I don’t know how many students I’ve taught,” she says modestly. But to her students, she’s a teacher like any other.

*Kreshma Fakhri writes for Killid, an independent Afghan media group in partnership with IPS. By distributing the testimonies of survivors of war through print and radio, Killid strives for greater public awareness about people’s hopes and claims for justice, reconciliation and peace across Afghanistan.

]]>Kabul’s seventh district is also called Sarzamine Sokhta in Dari (Burned Land). Nearly everyone here has lost a family member in the successive rounds of blood-letting witnessed by the city over the last three decades. In this testimony, Mir Abdul Wadood, now a teacher in a school in neighbouring Parwan, realls [...]]]>

Kabul’s seventh district is also called Sarzamine Sokhta in Dari (Burned Land). Nearly everyone here has lost a family member in the successive rounds of blood-letting witnessed by the city over the last three decades. In this testimony, Mir Abdul Wadood, now a teacher in a school in neighbouring Parwan, realls the year 1999 when Taliban dragged away and shot nine of his family members.

The green flags flags on the 10 graves in Parwan’s Laghmani village are visible from miles away. Credit: Killid

Among the dead that day were Wadood’s two grown-up sons, two nieces, two nephews and his wife’s two nephews. One other nephew, Abdul Hai, had a miraculous escape that allowed him to recount the story. Shot in the face, he managed to drag himself on to a road before collapsing. Passersby took him to Anaba Hospital in Panjsher, where he gained consciousness, and told them the exact location of the cold-blooded murder of nine other family members.

Wadood’s family, which hailed from Kabul and Karez Mir, north of the city, had sheltered in Parwan province to get away from the Taliban, who had formed the government in Kabul. But the Islamic fighters continued advancing north in pursuit of Ahmad Shah Massoud, an anti-soviet political and military leader who, together with his forces, had retreated to his stronghold in the Panjsher Valley.

On that fateful day in 1999, the Taliban arrived in a Datsun pickup truck Wadood’s home, and took away 10 young people, between the ages of 20 and 35 years. The captives, their hands tied behind their back, were take away and made to stand in a circle. Then, one by one they were dragged into the middle of the circle, and shot dead.

The dead, all between the ages of 25 and 35, were put to rest side-by-side in nine graves in Parwan’s Laghmani village. Today, the green flags that the family placed on the graves are visible from miles away, standing out between the yellow leaves of trees.

Killed by grief

“Unfortunately I was in Kabul at the time, and the way to Parwan was blocked,” says Wadood. “When I came back 40 days later, I went to the graves of the nine members of our family, including my two sons – one 29 and the other 25. I cried,” he says. “The graves were like swords in my eyes,” he adds.

But there was more bad news for Wadood. On his return from the graveyard he decided to visit his sister who herself had lost two sons and a daughter – to “share her grief,” he says.

“That is when relatives told me she had died. The fresh grave near the nine, which I had seen and prayed over, thinking it was a neighbour’s, was actually my sister’s. Her heart had failed from grief.”

Wadood gets up and shuts the door leading to an inside room where his wife is. He says she has been very disturbed ever since he told her that a journalist was coming to interview them about the death of their sons.

“My wife has never been the same since the deaths,” he says. “When the nine coffins were brought into the house everyone cried and screamed, but not my wife. Her voice was not heard. Her depression worsened when our elder son’s widow married again, leaving us to take care of their two children.”

Scarred forever

Wadood confides that their sons are never mentioned because it upsets his wife. “Laughter has left our house,” he says. “We never mention our sons. I have had to bury their remembrance along with them, I have no choice,” he adds.

Today, a third of his salary as a schoolteacher, which is roughly 6,000 Afs, or 110 U.S. dollars, is spent on medication for his wife.

His story is not unusual, Wadood says. Between 1996 and 2001, the Taliban and Massoud’s Northern Alliance fought for control of Parwan. Every time the Taliban won the province, the Shariah law was implemented. Parts of the province went back and forth from Taliban hands to Massoud’s. Hundreds of civilians died. The fighting ended with Massoud’s assassination by two suicide attackers believed to be al Qaida, on Sep 9, 2001 – two days before the bombing of the World Trade Centre in New York.

Three months later, in December 2001, U.S. forces invaded Afghanistan and ousted the Taliban starting a new chapter in the tumultuous history of Afghanistan and its civilian polulation.

* Sohaila Weda Khamoosh writes for Killid, an independent Afghan media group in partnership with IPS. By distributing the testimonies of survivors of war through print and radio, Killid strives for greater public awareness about people’s hopes and claims for justice, reconciliation and peace across Afghanistan.

]]>Esmatullah Mayar writes for Killid, an independent Afghan media group in partnership with IPS. By distributing the testimonies of survivors of war through print and radio, Killid strives for greater public awareness about people’s hopes and claims for justice, reconciliation and peace across Afghanistan. In this testimony, 55-years-old Mahparwar remembers Shab-e-Barat, “the Night of Forgiveness”, is an [...]]]>

Esmatullah Mayar writes for Killid, an independent Afghan media group in partnership with IPS. By distributing the testimonies of survivors of war through print and radio, Killid strives for greater public awareness about people’s hopes and claims for justice, reconciliation and peace across Afghanistan. In this testimony, 55-years-old Mahparwar remembers Shab-e-Barat, “the Night of Forgiveness”, is an Islamic holiday celebrating God’s mercy. People pray for forgiveness for those who died. It was on one such night of forgiveness, 21 years ago, that Mahparwar’s younger brother was killed by the mujahedin.

Mahparwar’s brother Mohammad Shafi was a cycle repairer in Kabul. The 19-year-old had just married a year earlier “And had a pair of twins — a daughter and son,” his sister recalls. He had no connection with any political party, she stressed, saying he was neither a member of Khalq nor Parcham — two communist parties that ruled Afghanistan after the assassination of president Daud Khan in April 1978. “He did not have a job with the government or any organisation.”

It was last days of the regime of President Najibullah, (1987 -1992) and the war between government forces and jihadist parties had engulfed the country, remembers Mahparwar. It was the 15th of Shoban, 1370 (July 5, 1991 in the Gregorian calendar), as they celebrated Shab-e-Barat, when tragedy struck.

“My brother was travelling to Jalalabad when armed people (mujahedin) came down from the mountains in Mashal Kandaw (on the highway between Kabul and Jalalabad), abducted and killed him immediately.”

His killers left his body on the roadside and fled, says Mahparwar.

“We got to know about his murder on Barat night but we could not find his body. My other brothers searched all over. Some of our relatives said they had seen our brother in their dreams, and we should search for him in the places they mentioned.

Her brothers searched everywhere. In the end they found him in a hospital mortuary.

Death of innocents

Mahparwar had been kept unaware, she says. “All they told me was that Shafi was injured, and was found in the Kabul hospital. But when I went to my father’s house I saw a friend of my brother, a soldier in the army, weeping loudly.”

“We buried him in Charqala village of Chardehe (Kabul province). My mother has not been well ever since.”

Shafi was the cleverest and most hardworking of her siblings says Mahparwar, working in his bicycle repair shop steadily through the winter and long hot summer. He did not waste his time in idle gossip, she says.

her sister-in-law, Shafi’s wife, finally remarried and took their son with her. “His name is Sahel, he looks very much like my brother,” she adds.

The situation in Kabul, meanwhile, went from bad to worse when Najibullah’s government was toppled by mujahedin forces, who then turned on one another. People fled the city in the tens of thousands. Mahparwar, too, became a refugee in Peshawar.

Bad news continued to pour across the border. “There was not one day when we did not hear of the death of relatives in Afghanistan. My younger sister’s husband was killed in the war between Hezb Islami and the Hezb-e-Islami led by General Dostum in Mazar-e-Sharif.”

Lost futures

In her childhood she had built castles in the air for her family, says Mahparwar, but the warlords “dashed everyone’s dreams and hopes”. All three of her brothers are poor, she says, one is a taxi driver, the other a labourer. A third is a mechanic. “The war took everything from us.”

Mahparwar’s children go to school, and she says she is happy for them. But she continued to be haunted by the fact that her brother’s killers are still free. “Arrest the murderers of my brother. Arrest the murderers of many others as well. They should be tried,” She says.

“They made us weep. They took away our breadwinners from us.” While her brother died on the night of forgiveness, for Mahparwar forgiveness is not within her reach, she says.

Instead, she wants for the stories of three decades of war to be told and remembered. She wasnts the to be collected and archived, so that “Future generations can see how our country was tyrannised,” she says.

Today, Mahparwar is a member of the Women’s Council in Chehelsotoon, in Kabul city, which was set up to support survivors of war.

]]>

Rahima lived in Iran as a refugee for seven years. She returned to Kabul in 2007. Photo: Najibullah Musafer/Killid

At the start of the war between the Taliban and mujahedin in 1996, Rahima lived with her family in Kabul’s Qala Jernail.

Emerging out of madrasas along Pakistan’s border with Afghanistan, the Taliban that year marched into Kabul and ousted mujahedin Ahmad Shah Massoud.

At the time, the mujahedin were in power under an agreement brokered between the different factions by the West after the collapse of the communist government of president Najibullah. But the agreement collapsed within months, leaving Kabul — which had survived the earlier years of war between the communists and the mujahedin – to be torn apart by rival guerrilla factions fighting for control over the city. In fact, the bloodshed was so terrible that Kabul residents welcomed the more disciplined Taliban fighters when they seized power and drove out the mujahedin.

But as history has shown that relief was short-lived.

Rahima says her family had lived peacefully in Kabul until the war broke ou.Her husband was a daily wage worker and they had a good enough life.

As the Taleban fought their way into Kabul, there was an exodus of civilians from the city, but Rahima’s family could not leave, because her husband had been jailed. “[The Taliban] jailed my labourer husband, and took him away to Paghman,” she says. He was finally released because they could not find any reason to keep him.

Turning breadwinner

The couple and their four children fled to safety to a village outside Mazar-e-Sharif called Babayadgar, where they lived for two years until the war caught up with them. The noise of rockets and rifles one night announced the arrival Taliban, eliminating anyone who crossed their path.

“They took my husband to a garden,” Rahima recalls of the day her husband was picked up. “We had no news of him for two days. Then we heard that a body was found in the garden — I went and identified it as his.”

Her husband gad been brutally tortured, his chin smashed with the butt of a rifle, his arms and legs broken.

Rahima brought her husband’s body home, washed and buried him with the help of neighbours. When she arrived back home, intruders forced their way into the house, burning everything.

The scared family fled into the desert until a modicum of calm had returned to the village. When they came back to their ruined home, Rahima had no money to buy even a bag of flour.

“The sky was far and the ground hard,” she says, reciting an Afghan proverb about the difficulty of the situation they faced.

A shopkeeper took pity on the family, and gave them loaves of bread to eat every night. But Rahima did not want to live only on charity. She made use of the relative security in Babayadgar to find work spinning cotton, sewing quilts and washing clothes – jobs that brought her small amounts of money.

The family succeeded in keeping hunger at bay, but the bitter cold of winter had to be endured. “We were putting on gloves and hats inside the house. Sometime we would put the lantern under the quilt to reduce the cold. We had no heater or stove to keep ourselves warm, and except God no one was there to help us in the city.”

Lucky break

In 2000 they made the journey back to Kabul. But faced with no prospect of work – women were not allowed to work under the Taliban – Rahima took the help of an “agent” to cross over into Iran with her children. She lived in Iran for seven years as a refugee, doing all kinds of work from washing carpets to factory jobs, to put her two daughters through school while her sons worked.

In 2007 she returned to Kabul having heard that the Karzai government was giving financial assistance to widows. She says she did not know that “such a fruit needs long hands to get”, meaning it was out of the reach of the poor. “We heard (in Iran) that Karzai was donating land to widows so we returned. When we came here we got no help from Karzai or the government.”

But luck was on her side in the form of new employment. Today, Rahima works in the office of the Killid Group where she is knows as “Aunt Fatima” and counted among its most hardworking and loyal staff.

*** Ali Arash writes for Killid, an independent Afghan media group in partnership with IPS. By distributing the testimonies of survivors of war through print and radio, Killid strives for greater public awareness about people’s hopes and claims for justice, reconciliation and peace across Afghanistan.

]]>Kreshma Fakhri writes for Killid, an independent Afghan media group in partnership with IPS. By distributing the testimonies of survivors of war through print and radio, Killid strives for greater public awareness about people’s hopes and claims for justice, reconciliation and peace across Afghanistan. In this testimony, Zubaida from the village of Qala Mullah recounts for [...]]]>

Kreshma Fakhri writes for Killid, an independent Afghan media group in partnership with IPS. By distributing the testimonies of survivors of war through print and radio, Killid strives for greater public awareness about people’s hopes and claims for justice, reconciliation and peace across Afghanistan. In this testimony, Zubaida from the village of Qala Mullah recounts for the firs time how she, thirty-two years ago, watched her husband being taken away by Soviet soldiers.

“It was the 2nd Sawr in 1359 (April 21, 1980),” Zubaida begins her account of the events that happened 32 years ago. “My husband was visiting us in Jaghatoo district, in Ghazni. A year before the communist government of Babrak Karmal had won power with the help of the Russians (then Soviet Union).” Many Afghans were angry, she said, and “drawn into a fight between Jihad and atheism” as she says – the one led by U.S.-supported mujaheddin, the other by the ruling government.

A man named Sayed Jagran was the commander of the anti-government forces in Jaghtoo district, where they lived. “In my village, Qala Mullah, he was carrying out propaganda against the government. But few people had the time for him. Most people were working on Bande Sardeh (a dam 28 kilometres away in south Ghazni).” Zubaida’s husband Mohammad Ismail was one of those who would come home on Thursday after a week of hard work, and return early in the morning on Saturday.

“One Thursday he came back and never went back to Bande Sardeh,” she says. Russian soldiers swarmed Qala Mullah after the Ashrars (anti-government forces) had already left the area. Only defenceless people remained. “ ‘Come out of your houses,’ the Russians shouted. We trooped into a compound — my husband was the first person they led away.

Zubaida and her six children tried to stop them, but he was taken away to nearby Qala Qata. “They took him to the centre of the village and shot him for siding with the opposition,” she remembers “They had no pity on anyone. They went from house-to-house killing all the men.”

In the end, they killed 21 of her relatives. Except for one farmer who escaped there was no male left to bury the dead, she says. “We ferried the bodies in a wheelbarrow, and buried them in a pit.”

“I tied a piece of red cloth on a pole on the top of our house so the Russians would not bomb us.”

]]>

Noor Wali Shinwarai writes for Killid, an independent Afghan media group in partnership with IPS. By distributing the testimonies of survivors of war through print and radio, Killid strives for greater public awareness about people’s hopes and claims for justice, reconciliation and peace across Afghanistan. In this testimony, Khaled Noor remembers his father, a [...]]]>

Noor Wali Shinwarai writes for Killid, an independent Afghan media group in partnership with IPS. By distributing the testimonies of survivors of war through print and radio, Killid strives for greater public awareness about people’s hopes and claims for justice, reconciliation and peace across Afghanistan. In this testimony, Khaled Noor remembers his father, a colonel in the Afghan army, who was imprisoned and killed for trying to restore republican rule.

In 1978, Eid al-Adha, one of the two main Muslim holidays, fell on a winter day, Khaled Noor remembers – perhaps less because of the festivities than the events that unfolded the night before.

As families prepared for the holiday, some 200 Afghan army officers gathered in great secrecy in the Asmar Division in Kunar province to discuss ways to restore the republic of Mohammed Daud Khan, Afghanistan’s first president, who had been overthrown in a coup d’etat by Noor Mohammad Taraki only six months before.

The division had an emergency airport, four residential blocks for army officers, many tanks, military vehicles and thousands of soldiers. But their attempt to restore republican rule, would be short-lived.

Lawyer Khaled Noor sometimes wishes “Our father would walk through the door and give us a hug”. Credit: Killid

Rise and fall

The leadership of the division was in the hands of the highly decorated Colonel Ghulam Dastageer Khan, son of the leader of the Shinwari tribe – and Khaled Noor’s father.

Years before, in 1964, he had been given the onerous task of marking out the international border with China in the Pamir mountains – a two-year endeavor that earned him awards from both countries, followed by an appointment as assistant of Sardar Wali Khan, the son-in-law of the Afghan king.

In 1973, Daud Khan overthrew the last king of Afghanistan, Zahir Shah, and founded the republic of Afghanistan.

By the time the communist party seized power through a coup in 1978, Khaled Noor’s father had become a colonel under Daud Khan.

By cutting off communications between the presidential palace and Kandahar, the communists initially managed to keep the colonel and other friends of the president in the dark about the fall of the leader.

When 200 of them finally came together back at the Asmar Division, their attempt to restore the president was in vain — Taraki soon had them arrested, imprisoned and tortured horribly.

Daud Khan’s assassination the same year was to plunge the country into decades of bloodshed and turmoil.

Colonel Khan’s children – Khaled Noor, Sardar Khan, Bilal, Spinghar and Mirwais – were still young when their father was arrested that wintery night before Eid al-Adha.

There was great excitement in the house over the coming feast. Suddenly there was a great banging on the front door. A military commander loyal to their father had come with bad news. “He told me, ‘Your father and all his friends have been arrested,’” Noor remembers.

“Though we were small, we knew that arrest meant death — the arrested never returned to their family. Our family and all the other families did not wear new clothes that Eid.”

The family was forced to vacate their house. Their things were put in a truck, and taken to Jalalabad. Khaled Noor says since they had no relatives in the city they went to their village in Haska Mena, Nangarhar. Their relatives saved the family from starving by sharing wheat flour and other food that they grew.

In Kabul, Hafizullah Amin, the second leftist president, overthrew Taraki. A military man came to their house with a letter for their mother.

Badly tortured

Writing from prison, Khan said that all his friends were killed in front of his eyes. “He said he was opposed to the communists, and he would never obey them,” Noor says. “He told my elder brother to look after the family.”

The man who brought the letter said their father was in Jalalabad jail and the family went to visit the prison laden with gifts for their father. But he had been tortured a lot and he was very weak, his son remembers.

In 1980, the year Babrak Karmal became the third communist president of Afghanistan, Colonel Khan died in prison.

The family was in mourning when the Soviets bombarded their village in Haska Mena district.

They fled across the border to Hango in Pakistan, where the two eldest brothers worked and the other siblings, including Khaled Noor, went to school.

Now, Mirwais, the youngest, is the head of a school in Kabul. Khaled Noor, meanwhile, is a lawyer working in a communications company in Kabul. “Life is good for us, “ he says. “But we still wish our father would walk through the door, and give us a hug.”

]]>Ebrahim Mahdawi writes for Killid, an independent Afghan media group in partnership with IPS. By distributing the testimonies of survivors of war through print and radio, Killid strives for greater public awareness about people’s hopes and claims for justice, reconciliation and peace across Afghanistan.

In this testimony, Seventy-year-old Abdul Husain from Deh Afghan remembers a [...]]]>

Ebrahim Mahdawi writes for Killid, an independent Afghan media group in partnership with IPS. By distributing the testimonies of survivors of war through print and radio, Killid strives for greater public awareness about people’s hopes and claims for justice, reconciliation and peace across Afghanistan.

In this testimony, Seventy-year-old Abdul Husain from Deh Afghan remembers a Russian attack on his village in the Nahoor district. Today, Nahoor, in Ghazni province, is picture postcard pretty: green with plentiful water from streams and rain. There are orchards of apricots, plums, prunes and other fruit. But three decades ago it was the site of a bloodbath.

The worst year was 1981, two years after the Soviet army rolled across the border into Afghanistan. Russian soldiers tried to fight their way into Nahoor through the Qeyagh pass. They bombed Deh Afghan and Sokhta Alawdani, the two villages closest to the border.

“The murdered people were all my relatives – one of my brothers, four cousins and so many others,” says Husain.

There are families who don’t know what happened to loved ones, while in village after village, the many physically challenged survivors are daily reminders of the bombings and killings.

Nahoor with its majority Hazara population was on the frontline of the war between Soviet soldiers and mujaheddin. Power in Kabul rested in the hands of Babrak Karmal, the third communist party president. Nahoor was the first district the Afghan fighters had wrested from the “Russians” as the Soviets were called. The Soviet army bombarded Nahoor from the air and with heavy artillery.

Terror everywhere

According to Husain, who is also known as Malak Abdul, even people in remote and mountainous areas of Nahoor were not safe from Russian “barbarity”. The terror was everywhere. There was no peace for civilians. Those who objected were tortured, and thrown in prison.

Russians entered people’s houses, and stripped it of all belongings. Buildings were demolished. Families fled the fighting and killing. The only people who remained were the mujaheddin.

“I also took my family to a safe area hoping to come back when it was safe,” says Husain.

While his younger brother and his family left, his elder brother and relatives stayed to defend the village. “My brother knew the Russians were coming but he was not aware they had already entered the village. He tried to save himself by moving to Ghara, a village adjacent to ours. But he did not make it,” he says.

Husain and his brother, their families and others from the village, kept walking. But there was no escaping the whine of fighter planes and pounding of shells. “It was terrifying. We did not know how to get away. We decided to go to the Siah Qul area where we thought it would be safer and out of the enemy’s line of firing,” he says.

Gunned down

One kilometre short of Siah Qul, a barren valley in the desert, the Soviet soldiers caught up with the fleeing civilians. “There was one kilometre to get to Siah Qul. Suddenly the desert erupted with the sound of tanks. The Russians had besieged the desert.

“We didn’t know the mountains above Siah Qul were the hideout of mujaheddin,” says Husain.

Russian tanks trained their guns on the winding procession of fleeing civilians. In the bloodbath that followed, only those who ran up the mountainsides survived.

“We were still in the middle of the desert when the Russian tanks started firing toward us from three sides. We ran as fast as we could toward Sia Qul valley. The only hope of escape lay in going into the mountains where the mujaheddin were hiding,” he recalls.

“My brother Jan Ali and some others were running helter skelter to save themselves. The group had scattered. But no one was able to save themselves. Russian tanks got them all in the end,” he says.

Sole survivor

The first one to go down was a relative called Sultan. A shot first got him in the leg. He was screaming, but the Russians had no pity, says Husain. “They sprayed him with bullets,”. Bodies littered the ground.

Husain still cannot fathom how he was the only person who escaped. “The invaders killed all of them. They fired hundreds of shots,” he says.

The Soviet soldiers eventually retreated after 24 hours in nearby Sokhta Alawdani, and men started trickling back into the village. “Women and children stayed away because there was still the possibility of the Russians returning,” he says. “We gathered together all the bodies of the dead.” They decided to bury the martyrs in one place, on a hill called Tapa e Karez. “It wasn’t a graveyard. The hill is called the hill of martyrs,” he says.

The Russians never came back to Nahoor and the village remained in mujaheddin hands until the Soviet army pulled out of Afghanistan in 1989.

]]>

Jamshed Malakzai writes for Killid, an independent Afghan media group in partnership with IPS. By distributing the testimonies of survivors of war through print and radio, Killid strives for greater public awareness about people’s hopes and claims for justice, reconciliation and peace across Afghanistan.

In April 1987, Afghanistan ratified the UN Convention against Torture. [...]]]>

Jamshed Malakzai writes for Killid, an independent Afghan media group in partnership with IPS. By distributing the testimonies of survivors of war through print and radio, Killid strives for greater public awareness about people’s hopes and claims for justice, reconciliation and peace across Afghanistan.

In April 1987, Afghanistan ratified the UN Convention against Torture. But it did not stop the government nor its opponents from using torture to punish and extract information from political rivals. The crimes were never probed; the victims were never compensated.

Nayeem Jan, 46, a resident of Shewa district in Nangarhar province, was nearly beaten to death in a prison run by a mujaheddin commander. Death would have been an escape from the torture, he says.

He was the star pupil of his school, Sayed Jamaludin High School, and a good trader before the war came to Shewa.

“I graduated in 1977 (two years before the Soviet troops entered Afghanistan). I had many dreams like my peers. I wanted to join the government, and be a good officer, but luck did not favour me and I got into business like my father,” he says.

He continued to do business through most of the Soviet years. In 1988, Shewa district was captured by mujaheddin, and his life changed forever.

“I was sleeping deeply – it was 5 o’clock early morning that the war started in the district,” he recalls. “We thought of fleeing but nobody could move. The mujaheddin had already entered the district governor’s building,” he adds.

He had no idea which faction of the mujaheddin had captured the district, he says. At nine o’clock the next morning he saw the flag of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar hanging in one of the towers of the district building. “We were very fearful,” he recalls. “The mujaheddin were searching the houses and asking for guns. They kicked down the door to our house, and a group of armed people entered.”

Ruined by war

The next hour was going to be the most tragic in his life. “My 13-year-old sister was injured seriously. They took my elder brother, two uncles and me. They put my two uncles in a room full of hay and set it on fire, killing both. They said my uncles were communists. Both of them were teachers,” he says, sadly.

The mujaheddin commander kept Jan in a private jail in the Mohammad Gat area of Kunar province. During his two-months imprisonment guards tortured him to force a confession.

“They were asking me to confess (to being a communist), but as I had not done anything wrong I had to deny. They kept beating me till I fainted. I had heard terrible stories of torture of communists, but the torture by this commander was unimaginable. You can still see the marks on my body,” he says.

Jan’s family had a good name in Shewa district. “We had good flocks (of sheep and goats) and business, we had a bus. But the armed men took everything.”

The family left Shewa district for Jalalabad city and later Peshawar, where Jan bought a horse and drove a buggy. “My brother started work in an iron factory and my father was working as a daily labourer wherever he could find work,” he says.

One more move and eight years of poverty later, Nayeem’s parentls had both died, now making him head of a family that included his much younger sisters, and his own five children.

When the family returned to Afghanistan in 1999, “The country was hell,” he recalls. “There was nothing but war. So we went back to Pakistan, and we became vegetable and fruit hawkers. We would push a cart the whole day,” he says.

No reprieve

In 2003, he heard about the new government in Kabul on the radio. He heard stories of how people were being rehabilitated. Almost overnight the family packed their bags and pnce again returned to Afghanistan. Jan hoped he would get a “good job”. But it was not to be so.

Now his sons and he eke out a living as daily wage workers. “I wish there had been no revolution,” he says.

The Najibullah government at least was giving food rations to all its officers, Jan remembers. Today, “No one is giving us anything…”

]]>